Andrea Mantegna was one of the most striking artists of the North Italian Renaissance. Known for his graphic style and innovative approach to perspective, he was a collector of antiques and an archaeologist deeply immersed in classical culture. Mantegna’s artistic upbringing in Northern Italy granted him a great intellectual basis that he applied to his painted works as well. Read on to learn more about the five most important works by Andrea Mantegna.

1. Saint Jerome in The Wilderness: Andrea Mantegna’s Earliest Known Work

According to Giorgio Vasari, Mantegna came from a poor family and worked as a shepherd as a child. At age eleven, he became an apprentice of a famous painter from Padua, where he copied ancient artifacts and assisted the painter with his commissions. Padua was the center of Renaissance science and intellectualism, and there, Mantegna picked up the basic components of his own work—his sharp drawing style and the intellectual complexity of his compositions, filled with symbols and contextual hints.

One of Mantegna’s earliest works that survived centuries was his depiction of Saint Jerome, the patron saint of scholars, librarians, students, and archaeologists. Jerome converted to Christianity at a mature age, denounced his previous life of sin and depravity, and became a hermit focused solely on Bible studies. He was the one who translated both the Old and New Testaments into Latin, making them more available to scholars.

Mantegna painted Jerome near his cave, where he isolated himself, holding a book and prayer beads. Near his feet, hidden behind the rocks, is a lion. According to the legend, the injured animal once came to Jerome’s cave, and instead of hiding in terror, the saint approached it and took a thorn out of its paw. Transformed by this act of kindness, the lion remained with Saint Jerome, guarding his cave.

2. Adoration of the Shepherds

Mantegna often painted recognizable religious scenes, yet many of them are hard to appreciate without reading the contexts, coded in the symbols and decorations. For instance, Mantegna’s version of the shepherds’ visiting infant Jesus in his crib holds much more information than a simple retelling of the subject. For instance, the fence behind the figure of Saint Joseph on the left side of the composition refers to the painting’s commissioner. Although no papers have survived, art historians managed to uncover that Mantegna created this work for Borso d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara. The Duke was famous for draining swamps around Ferrara by building dams similar in structure to the fence.

Moreover, the natural decoration around the figures—flowers, fruits, and grass—may refer to the popular dispute of Mantegna’s time. Some of his educated contemporaries argued that poetry was more suitable for depicting the natural world than painting due to the unlimited expressive potential of words. It is possible that Mantegna decided to prove otherwise by including realistic elements of the landscape in his work.

3. Camera Degli Sposi Frescoes

Perhaps the most monumental of Mantegna’s projects was the series of frescoes for the Palazzo Ducale in Mantua. Mantegna painted a bridal room (Camera degli Sposi) intended for small semi-private gatherings of the Gonzaga family members. The frescoes included a large family portrait, as well as scenes of leisure that aimed to indicate their affluence and education.

Mantegna was an amateur archaeologist; thus, he had a rather vast knowledge of antique architecture and design, which he incorporated into his paintings. His frescos for Camera degli Sposi visually enlarge the space by creating the illusion of windows and niches. The ceiling panel imitates an oculus—a ceiling window created to let the natural light into a building. From the balustrade of the oculus, the visitor is observed by angels and ladies-in-waiting. To further enhance the sense of realism, Mantegna painted a potted plant about to tip over and fall onto a visitor’s head.

4. Saint Sebastian

Saint Sebastian was a secret Christian who practiced and preached his faith despite the prosecution ordered by the Roman Emperor. The scene of Saint Sebastian’s execution had great expressive potential. It was favored by many artists from the Middle Ages and on. In Mantegna’s version, Sebastian appeared as a living antithesis to the pre-Christian culture. Under Sebastian’s feet lay scattered broken pieces of ancient sculptures behind him—the remnants of old temples. These decorations have a symbolic meaning, indicating the inevitable death of the pagan past and the triumph of the Christian world that would happen regardless of the saint’s death.

According to the legend, Sebastian secretly destroyed more than two hundred pagan idols, aiming to eradicate non-Christian faith. The cloud in the bottom left corner, reminiscent of an equestrian figure, is usually associated with one of the Horsemen of Apocalypse—Death on a pale horse. Centuries after Sebastian’s alleged execution, he became a spiritual protector of Italians against plague, the most ruthless carrier of death known to Mantegna’s contemporaries. The artist survived several outbreaks of the disease and started working on his image of Saint Sebastian after he managed to recover from the plague in 1456.

For his beliefs and actions, Sebastian was tied to a tree and shot with arrows but miraculously survived and continued preaching. Curiously, the iconography of Saint Sebastian has a lot in common with the story of Baldr, the Scandinavian god of spring and renewing life cycle. Baldr’s death similarly included him, a young and strikingly beautiful young man, being shot at with arrows. Unlike Sebastian, Baldur had no doubts about his miraculous survival until the trickster god Loki found a way to overcome the protective spell put on Baldur by his mother.

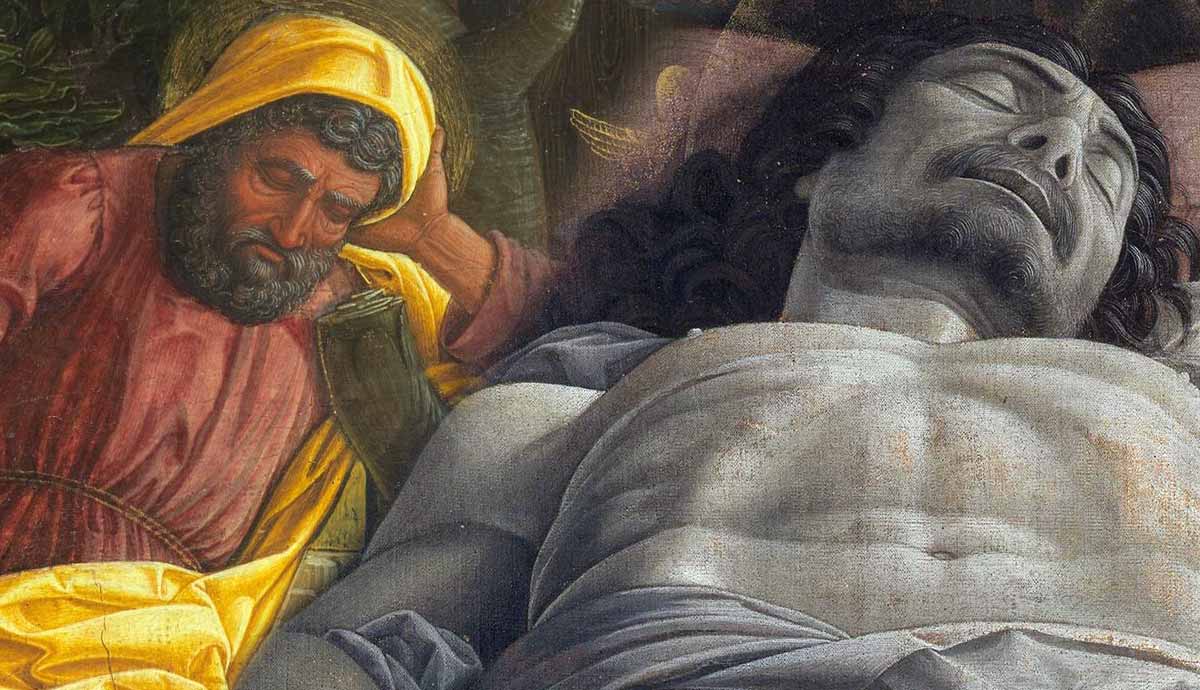

5. Lamentation Over the Dead Christ: Andrea Mantegna’s Most Famous Work

The most famous and frequently discussed masterpiece of Andre Mantegna opened the doors towards experimenting with perspective for generations of artists. The subject of the lamentation of Christ is traditional, if not typical, for Christian art of his era, and yet Mantegna managed to bring innovation into the fixed canonical image. The scene happens almost immediately after Jesus’ dead body is removed from the cross and is surrounded by his grieving followers. Some interpretations of the story include the Virgin Mary’s lamentation of her son, as depicted in the famous Pieta by Michelangelo. Although the subject became immensely popular during the Middle Ages, it was never part of the Biblical canon, found only in apocryphal stories.

Mantegna used the inverted perspective to achieve a unique sense of standing right next to the dead Savior’s feet rather than looking at a flat image. Instead of painting Christ’s head smaller than his feet, which was typical for the linear perspective, he kept the proportion of body parts natural. Apart from the extremely naturalistic effect, it helped Mantegna avoid focusing the viewers’ attention on the feet instead of the entire figure. Despite shortened body parts and manipulation with proportions, the figure seems whole and substantial.

Although we are used to perceiving linear perspective as something natural, it was the mathematical invention of Mantegna’s era, created specifically to create an illusion of depth in flat spaces. Moreover, art historians and scientists insist that inverted perspective, as seen in medieval art, is actually more natural to the human eye. The main proof of it, apart from subjective human experience, is how children render the world in their drawings. Before they become familiar with the basics of art or mathematics, they intuitively choose the inverted perspective to represent objects around them.

Andrea Mantegna’s Impact

Mantegna’s work was quoted by many artists over the centuries, both in terms of their pictorial qualities and their manipulation of space. Yet one of the most striking examples can be found in the works of the controversial photographer Andres Serrano, the frequent guest of ratings of the most outrageous and scandalous artists ever. His 1992 series The Morgue is a rather unsettling exploration of mortality and our relationship with it through a collection of images of dead people of all ages and social groups. Some of them endured violent deaths, and some passed away peacefully.

While battling their inherent terror and repulsion, the viewer still cannot escape associations with the Medieval and Renaissance paintings, with gruesome images of suffering and violence omnipresent. The unnamed characters of Serrano thus become equal to the bodies of Christian saints who endured violence and became immortalized in works of art. One of the images—a photograph of a man who died from a gunshot wound—is a direct quote from Mantegna’s Lamentation of Christ, despite the fact that the image is reversed. Instead of standing at the man’s feet, the viewer becomes this man who lies motionless on the morgue table.