Aristotle’s cosmology proposes a divine blueprint for the cosmos, one that envisions an ordered and hierarchical universe set in motion by an unmoved divine cause. His cosmological model is based on physical, astronomical, and philosophical observations that left a lasting imprint on our understanding of the world. In this article, we examine the defining characteristics of the Aristotelian cosmos and its intricate connection to the divine.

An Overview of Aristotle’s Cosmology

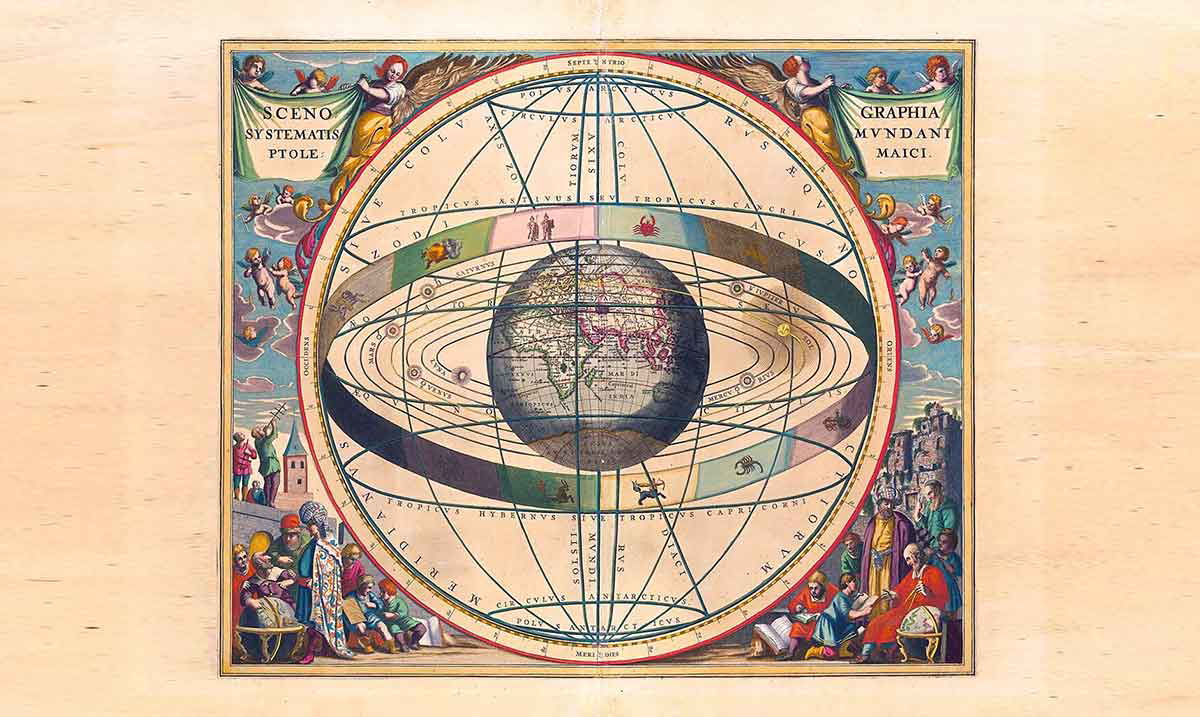

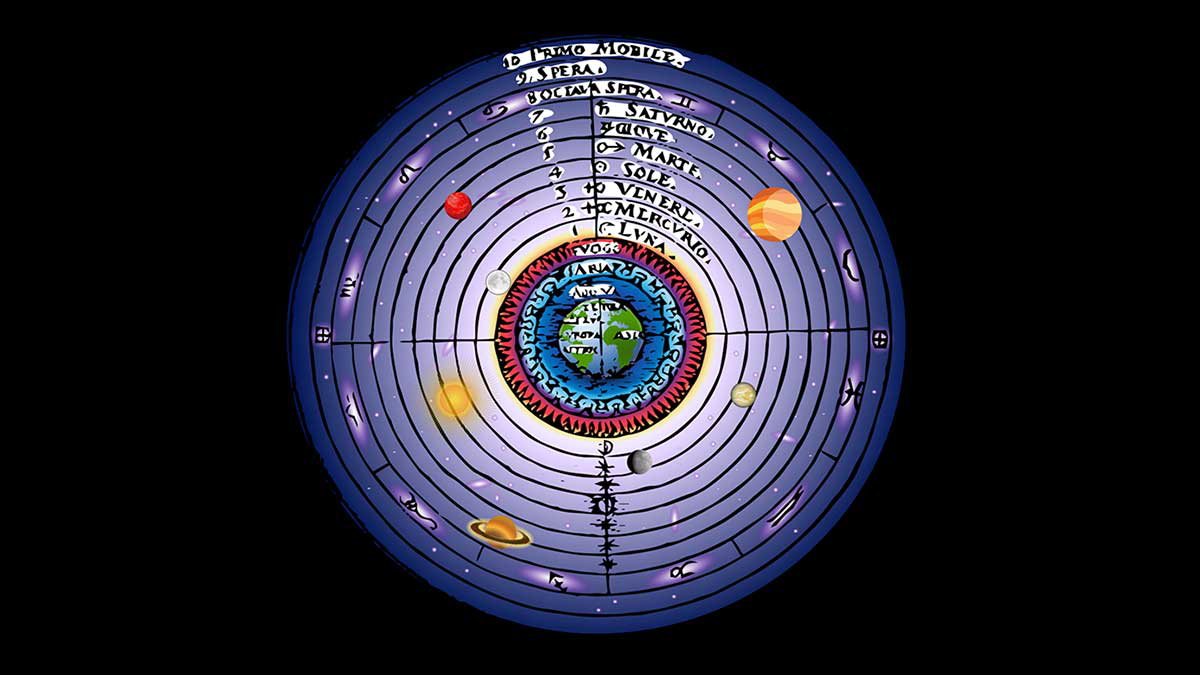

Aristotle depicts the cosmos as an all-encompassing, unique, and perfectly spherical Whole. It consists of multiple concentric spheres, akin to an onion. The Earth is situated as the motionless center of that cosmos, around which the celestial bodies revolve in an ordered and hierarchical manner. The universe, for Aristotle, is both spatially finite and eternal. In other words, it is limited in space, but unlimited in time.

He divides the cosmos into two main regions, the sublunary and supralunary, each differing in terms of substance, physics, and connection to the divine. The Prime Mover is considered the divine principle underlying Aristotle’s blueprint of the cosmos. It is the ultimate and supreme metaphysical cause of motion in the entire universe and is itself unmoved. Alternatively, the unmoved movers, though inferior, share in the divine status of the Prime Mover as the metaphysical causes of particular motions in the supralunary domain.

The Sublunary Region of Aristotle’s Cosmos

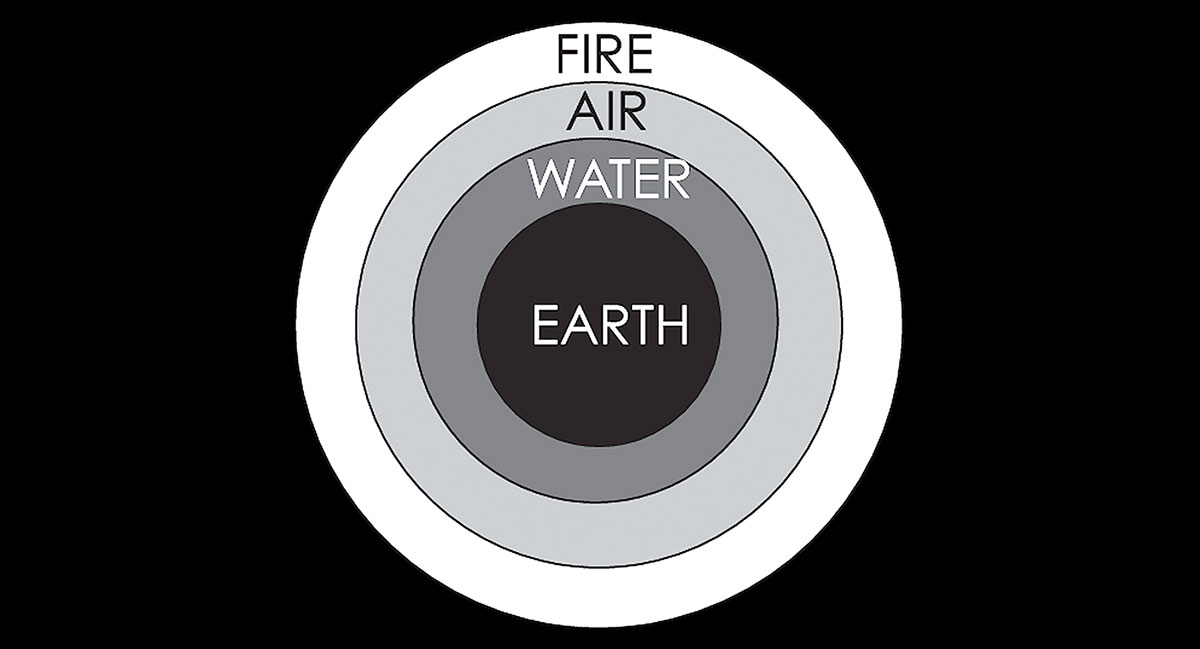

The sublunary region is at the heart of Aristotle’s geocentric cosmos, containing the Earth and its atmosphere. It is the realm of change and transience, where everything undergoes generation and corruption. The sublunary region consists of the four classical elements – earth, water, air, and fire. Aristotle attributes certain qualities to the four elements: earth is cold and dry, water is cold and wet, air is hot and wet, and fire is hot and dry. Each of these elements is hierarchically organized in concentric spheres according to its density. Earth, as the heaviest element, is the sphere at the center of the sublunary domain, followed by water, air, and, finally, fire.

All physical bodies in the sublunary region consist of a combination of the four basic elements, with one or two elements predominating in their composition. A physical body naturally moves towards the concentric sphere of its predominant element. For example, a rock will fall downwards towards the center, whereas a flame will move upwards towards the fiery sphere. This is what Aristotle calls ‘natural motion’, the inclination of an object to move towards its natural place, which constitutes its telos (or goal). Once an object reaches its natural place, it comes to rest. From here, Aristotle argues that motion in the sublunary region is linear and finite, because each element either moves from or to the center until it reaches its natural resting place. In other words, each cycle of motion is rectilinear and has a definitive beginning and end.

Elemental Motion

That being said, “Aristotle explicitly denies that the elements are self-movers and thereby denies that their nature is an efficient cause of their movements” (Scharle, 2008). In other words, the natural motion of an element only determines the form of its motion, but is not itself the cause that generates its motion. Aristotle proposes that the motion of the celestial bodies of the supralunary region is the indirect efficient cause of elemental motion in the sublunary domain.

Hence, every motion in the terrestrial region “is part of a causal chain that correlates with celestial motion and traces its origin back to the rotation of the first heaven”, which is the outermost sphere of the fixed stars (Botteri and Casazza, 2023). For example, the annual and daily motion of the sun causes changes in heat and moisture, which are defining qualities of the elements. As a result, water (cold and wet) becomes air (hot and wet) when cold is substituted by hot, and vice versa. In simple terms, we can consider the supralunary region as the indirect ‘mover’ of the sublunary region.

The Supralunary Region and the Divine Principle

The supralunary region extends from the lunar sphere to the outermost sphere of the cosmos. It is the abode of the moon, the sun, the planets, and the fixed stars, each one of them residing in a rotating concentric sphere. Unlike the sublunary region, everything in the supralunary region consists of a special element called ether. In On The Heavens, Aristotle describes ether as the nearest element to the divine due to its perfect and eternal natural motion. Unlike the rectilinear motion of the sublunar elements, the natural motion of ether is circular.

Circular motion is continuous and eternal because a circle, unlike a line, has neither a beginning nor an end. Hence, everything in the supralunary region is eternal, changeless, ungenerated, and imperishable. For all these reasons, Aristotle considered the supralunary region more perfect than the sublunar domain.

Causes of Motion

The question yet to be answered is what causes the motion of the supralunary region? Given that every movement needs a mover and the Aristotelian cosmos is spatially finite, the series of movers-moved cannot indefinitely extend. As a result, all the series of motion must start with a first mover that is itself unmoved. The Prime Mover is the divine, metaphysical, and immaterial unmoved mover that is the original source of motion in the entire cosmos.

It is the direct cause of the rotation of the sphere of the fixed stars (the outermost sphere of the cosmos), thereby indirectly causing the rotation of all the subordinate celestial spheres it carries, which, as we’ve established, cause motion in the sublunary region. So, the hierarchy of cosmic motion can be simplified as follows: 1) Prime Mover, 2) Sphere of fixed stars, 3) The celestial spheres of the planets, sun, and moon, 4) The sublunary elements.

Unmoved Movers

Aristotle argues, however, that the intricate motion of the celestial spheres cannot all be explained by the movement of the sphere of the fixed stars. Hence, in Metaphysics, he proposes that, in addition to the Prime Mover, there are multiple unmoved movers that cause each motion in the supralunary region that the motion of the fixed stars doesn’t account for. As Botteri and Casazza explain in The Astronomical System of Aristotle, these unmoved movers are finite in number, each associated with a celestial sphere. Like the Prime Mover, the unmoved movers are divine, metaphysical, and immaterial. However, they are subordinate to the Prime Mover because they are not responsible for the motion of the entire cosmos, but only partially responsible for the motion of the celestial spheres.

The Prime Mover and unmoved movers constitute the divine principle in Aristotle’s blueprint of the cosmos. In Metaphysics, Aristotle poetically explains that they produce motion, not by physically moving the spheres, but “by being loved”.