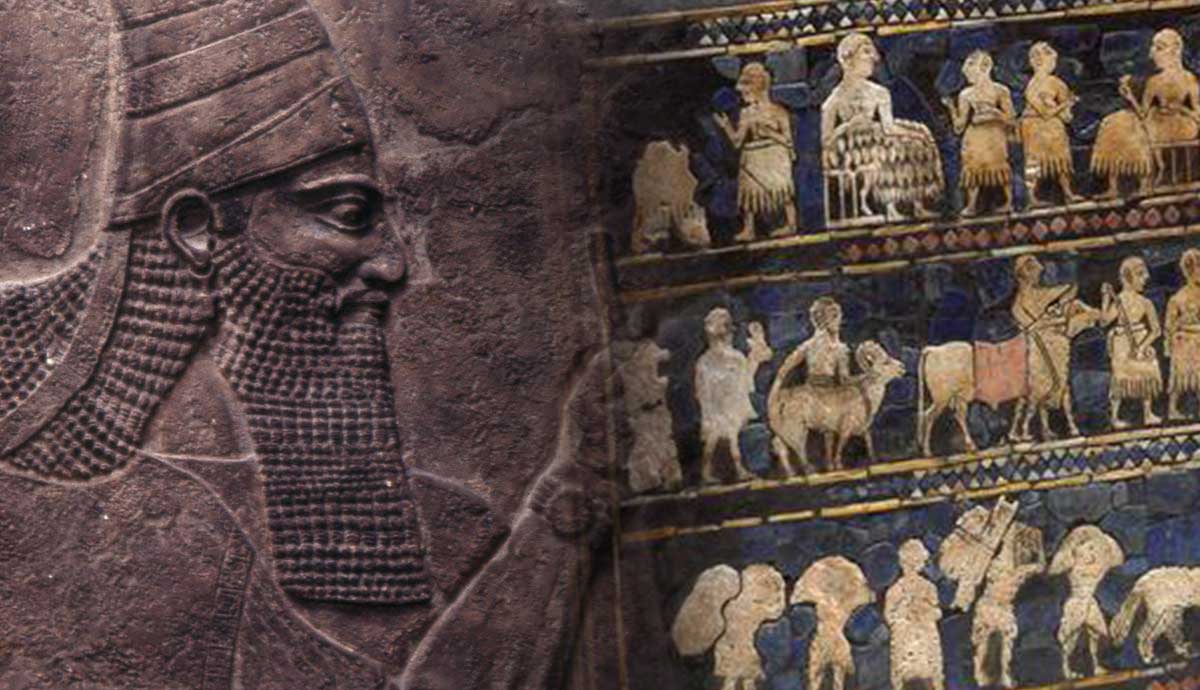

The Assyrian Empire grew out of the city of Assur, which was named for the principal god of Assyria, and became a significant military power. Meanwhile, Babylon was under the patronage of the god Marduk and was known as an important cultural and religious center in the region. The two kingdoms frequently came into contact through local politics. Their history is characterized by Assyria trying to exert control over Babylon, but not fully subjugating the city out of respect for their gods, giving the Babylonians the opportunity to rebel and reassert their autonomy. In the constant back and forth, the two powers sometimes seemed like friends, and sometimes foes.

Origins as Early Rivals

The Sumerian civilization appeared around 6000 BCE in the area between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in southern Mesopotamia. By the 23rd century BCE, Sargon of Akkad, known as Sargon the Great, had conquered the Sumerian lands and effectively launched his Akkadian Empire, the first great empire in world history.

Evidence shows that both the Assyrian city of Assur and Babylon existed in this period. Archaeological remains at the site of Assur suggest the site had been inhabited since the early 3rd millennium BCE. Babylon is referenced on a clay tablet dating to 2217–2193 BCE. After the fall of Akkad, and a brief period of stagnancy in international politics, the Third Dynasty of Ur, a Sumerian kingdom, rose to fill the void. Ur was then sacked by the Elamites, and a wave of Amorite influence (Semitic-speaking people from the Levant) spread across Mesopotamia.

Until this point, Babylon had been a small but well-respected religious hub in southern Mesopotamia. Sumu-abum, a local Amorite chieftain, secured Babylonian independence from the Akkadian empire sometime between 1897-1830 BCE. Following in Sumu-abum’s footsteps, around one hundred years later, Hammurabi transformed the settlement into a dominant city. From c. 1770-1670 BCE, Babylon was the largest city in the world. Hammurabi expanded Babylon’s territory significantly and much of southern Mesopotamia came to be known as Babylonia.

But Babylon was only one of many emerging powerful city-states. Another affluent civilization called Assyria was flourishing in northern Mesopotamia.

The Amorite King Ila-kabkabu of Ekallatum, the neighboring state of Assur, had been conquered by Naram-Sin of Eshnunna, causing Ila-kabkabu’s successor, Shamshi-Adad, to flee to Babylon. Upon Naram-Sin’s death, Shamshi-Adad usurped his throne. In 1790 BCE, he dethroned the King of Assur, Erisum II, who was the son of Naram-Sin. Shamshi-Adad I declared himself king of a growing number of city-states in upper Mesopotamia and continued to conquer yet more land, including areas of Syria and Anatolia. He was the first great king of Assyria.

However, Shamshi-Adad I’s growing influence would not last. Hammurabi, who was king of Babylonia from c. 1792-1750 BCE, fought with Ishme-Dagan I, Shamsi-Adad I’s successor, for control over Mesopotamia. Hammurabi was victorious, and the Assyrian king had to pay tribute to Babylon.

Instability and Rising Power

The death of Hammurabi spelled the beginning of disaster for the Old Babylonian Empire. His son and successor, Samsu-iluna, could only watch as all the land conquered by his father rebelled and fractured. Chaos ensued as the city-states of Eshnunna and Larsa revolted against their Babylonian leaders, and Assyria and Elam took full advantage of the political disarray.

Asinum, King of Assyria and grandson of Shamshi-Adad I, was expelled due to his Amorite heritage and Babylonian connections. A period of Assyrian civil war followed, and Ashur-dugul emerged as king. He ruled only briefly before he was also usurped, this time by six unhappy officials. At some point, one of these men, named Adasi, a supposed native Assyrian, was crowned king. He is typically missed from Assyrian king lists, which skips straight to his son, Bel-bani. This era is often defined by historians as the Assyrian “Dark Ages” because of the disorder and lack of reliable sources. However, Bel-bani has been historically credited with stabilizing the Assyrian kingship. His Adaside Dynasty would go on to rule for the next millennium.

At the same time, Babylon and Hammurabi’s descendants continued to decline in power. In 1595 BCE, the Hittites sacked Babylon but made no attempt to maintain control of the city. Nevertheless, the main cultural and once political power in Mesopotamia had been destroyed, creating the opportunity for new powers to surface.

The Kassites (assumed to be tribes from the Zagros mountains) seized control of Babylonia, and the Mitanni emerged in the north. Despite not being a dominant power, Assyria enjoyed a period of relative peace and entered into diplomatic relations with the Kassite-Babylonians. Meanwhile, the Mitanni grew in strength and, like the ruling city-states of previous centuries, began to exercise power over neighboring states. Assyria was taken over by the Mittani around 1430 BCE, but would be independent once more just seventy years later. Ashur-Uballit I (c. 1363–1328 BCE) secured Assyrian autonomy by taking advantage of conflict between the Hittites and Mitanni.

While the Assyrian state fought to assert itself amongst the assembly of rival city-states, Babylon maintained a period of order. The Kassites unified Babylonia under one ruling body, reinstalled favorable trade routes, and revitalized the area through vast construction projects. During this period, successful international affairs were recorded through the famous Amarna Letters, detailed correspondence written in cuneiform between the Egyptian pharaohs and various civilizations in the ancient Near East, including the Kassite-Babylonians and Assyrians.

During the 14th century BCE, both Assyria and Babylon were experiencing frequent and increasingly longer periods of stability. The Assyrians were escalating their involvement in international affairs, while Babylon was renovating itself from the inside through reforms.

Assyrian Control of Babylon

The period scholars refer to as the Middle Assyrian Empire began with the reign of Ashur-uballit I. The subsequent Assyrian line of succession produced several warrior kings, namely Adad-nirari I, Shalmaneser I, and Tukulti-Ninurta I.

Adad-nirari I set his sights on subjugating the established state of Babylonia. He took towns on the Babylonian border, then met the Babylonian king, Nazi-Maruttash, in battle and defeated him. Under Shalmaneser I, Adad-nirari’s son, the Assyrian focus shifted towards the constantly rebelling Mitanni. But Tukulti-ninurta I resumed an emphasis on securing southern Mesopotamia.

Tukulti-Ninurta I assumed the Assyrian throne in approximately 1243 BCE. Historians generally consider Tukulti-Ninurta I’s prioritization of Babylonian subjugation as one of economic and political gain. However, Tukulti-Ninurta I claimed in an epic poem about his deeds that the Babylonians had attacked Assyrian settlements and that their king, Kashtiliash IV, had been renounced by the gods. This was likely state-produced propaganda to validate the Assyrian attacks. Tukulti-Ninurta I won the war in 1225 BCE, but at a heavy cost, according to contemporary sources.

The Assyrians allowed the Babylonians significant freedoms. Much of the land that the Assyrians had conquered in southern Mesopotamia was governed indirectly through vassal kings. In 1221 BCE, Tukulti-Ninurta I visited Babylonia and made offerings to the Babylonian gods, which demonstrated that the ruler of Babylon, Adad-shuma-iddina, was favored by the Assyrians. Likewise, this evidence shows that the Assyrians viewed Babylonian culture and religion with great respect.

Peace between the two states lasted only until 1217 BCE. Tukulti-Ninurta I had already pardoned Adad-shuma-iddina for one uprising, but the Babylonian king tried again. The Babylonians were met with their third Assyrian campaign under the rule of Tukulti-Ninurta I, which once again ended badly for the Babylonians. Babylon was plundered and vandalized, and Tukulti-Ninurta I carried off an important statue of Babylon’s patron god, Marduk.

But the Babylonians did not give up. Adad-shuma-usur led another rebellion, which was successful in expelling the Assyrians in 1216 BCE. Tukulti-Ninurta I was assassinated around 1207 BCE. Historians surmised his murder was the result of his increasingly sacrilegious behavior, including stealing religious idols and declaring himself a god. The death of Tukulti-Ninurta I saw Assyria enter a period of inactivity that coincided with the collapse of the Bronze Age. Nevertheless, the state fared well in comparison to many other civilizations in the Near East.

Increasing Hostilities

Babylon had conclusively become an autonomous state after the death of Tukulti-Ninurta I. His son and successor, Enlil-kudurri-usur, was defeated so badly by the Babylonians that the Assyrian officials handed their king over to them. Ninurta-apal-Ekur was the son of one of these officials and was backed by the Babylonians to seize power over Assyria. Ninurta-apal-Ekur proved ineffectual, and instability in Assyria continued.

Babylon was not faring any better. King Zababa-shuma-iddin faced the Assyrian forces that had annexed Babylonian land in the north while also taking on the Elamite king who invaded from the east because he stated he had a stronger claim to the Babylonian throne. Elam devastated many Babylonian cities and took multiple important artifacts back to Susa, including the Code of Hammurabi. The next and final Kassite-Babylonian King, Enlil-nādin-aḫe, was brought to Susa in chains along with many other Kassite-Babylonian noblemen. In 1155 BCE, the Kassites had been conclusively defeated, and the Elamites took Babylon’s statue of their patron god Marduk with them.

Only a few years later, in 1153 BCE, Marduk-kabit-ahheshu ascended the Babylonian throne and expelled the Elamites from Babylon. He was succeeded by his son Itti-Marduk-balatu. Meanwhile, in Assyria, the death of Ashur-dan I in 1133 BCE generated another Assyrian power struggle between his two sons. After Mutakkil-Nusku emerged triumphant, he immediately went to war with Itti-Marduk-balatu. The two city-states fought for control over the city of Zaqqa (or Zanqi), and the conflict passed down to both their successors.

Another Babylonian, King Nebuchadnezzar I, took up this fight but the Assyrian ruler, Ashur-resh-ishi I, frequently led the Assyrians to victory. As a result, Ashur-resh-ishi I professed himself as “the avenger of Assyria.” Nebuchadnezzar I was successful on the battlefield elsewhere as he conquered Elam and returned with the sacred statue of Marduk.

Relations between Babylonia and Assyria grew in hostility at the end of the reign of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser I (c. 1114-1076 BCE). The two nations fought at least twice. Initially, these sour dealings were resumed under Tiglath-Pileser I’s successors, but were then resolved by the later Assyrian king, Ashur-bel-kala. He installed Adad-apla-iddina to the Babylonian throne and then married his daughter to ensure peace. This securely placed Babylon in the sphere of Assyrian influence and, therefore, was effectively an Assyrian vassal state.

The Rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Decrease of Babylonian Power

After the reign of Ashur-bel-kala, Assyria was in a holding position, and there was little conflict between Assyrian cities and other Near East city-states. Babylon remained under Assyrian authority and also experienced a steady stream of Semitic foreign peoples settling in the area, with the Chaldeans being the last group in the 9th century BCE.

The Middle Assyrian Empire ended in 912 BCE with the death of Ashur-dan II. The ascension of Adad-nirari II in 911 BCE marked the rites of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. This was a new period of expansion, and the new king began to subjugate lands previously associated with Babylonia. He also reinforced diplomatic relations with his southern neighbor through a marriage agreement. Adad-nirari II married the daughter of the Babylonian King Nabu-shuma-ukin I and vice versa.

Following in the footsteps of Adad-nirari II came a host of warrior kings who were fully committed to imperialism in the name of the Assyrian gods. Principal among these warrior kings were Ashurnasirpal II and Shalmaneser III. Shalameneser III’s son and successor, Shamsi-Adad V, successfully defeated Babylonian rebellions and claimed for himself the traditional Babylonian title of “King of Sumer and Akkad.” However, this victory was minimal as Shamsi-Adad V was unable to capitalize on the weakened state of Babylon due to Assyria’s failed campaigns against other kingdoms.

It would not be until the reign of the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III, over 60 years later, that Assyria would make considerable gains in Babylonian territories again. At the start of his reign, Tiglath-Pileser III fought against the Babylonian King Nabu-nasir and conquered many regions under Babylonian control. After a period of expansion elsewhere, Tiglath-Pileser III used the ascension of the Chaldean Nabu-mukin-zeri to the Babylonian throne as an excuse for full-scale war.

Tiglath-Pileser III conquered Babylon but wanted the Babylonian people to accept him as ruler due to Assyria’s immense appreciation of Babylonian culture. Therefore, he took part in the traditional New Year celebrations in honor of Marduk, and Babylon was not carved up into provinces as was the typical Assyrian mode of conquest. Instead, Babylon was held in a personal union which means it shared a monarchy with Assyria but its religion and traditions remained intact.

Sack of Babylon

Babylon rebelled and restored its autonomy early in the reign of Sargon II (c. 722-705 BCE) through an alliance with the Elamites. Babylon, along with many other Assyrian vassals, seized the opportunity to rise after Sargon II usurped the throne from Shalmaneser V, which resulted in hostile infighting within Assyria.

By 710 BCE the Babylonian-Elamite alliance had deteriorated and Sargon II exploited the situation by invading Babylo. When he got there, he was allowed into the city with minimal opposition. Sargon II became King of Babylon and spent the next three years there where he immersed himself in the local customs. Assyria was effectively ruled by his son, Sennacherib.

Upon Sargon II’s unexpected death in battle, Sennacherib dissociated himself from his father. Sennacherib, as well as his later successor, Esarhaddon, were both said to be suspicious of Sargon II’s position in Babylon. They, and many Assyrian vassal states, probably saw Sargon II’s death as a sign from the gods. Accordingly, many nations ruled by Assyria rebelled upon the ascension of Sennacherib.

During his reign, Sennacherib reconquered Babylon after an earlier revolt led by Merodach-Baladan, who had ruled before Sargon II’s victory over Babylon. Sennacherib’s conquest took two years, after which Merodach-Baladan escaped to Elam and Sennacherib proclaimed himself as King of Babylon. However, unlike his Assyrian predecessors, he took no part in Babylonian traditions, which the Babylonians understood to be disrespectful.

More rebellions led by Merodach-Baladan ensued, which Sennacherib subdued. He established Bel-ibni, a Babylonian noble who had been raised at the Assyrian court, as a new vassal king. But Merodach-Baladan and Shuzubu, a Chaldean tribal leader, fought amongst themselves for the Babylonian kingship. In another attempt to quell discontent, Sennacherib appointed his son, Ashur-nadin-shumi, as King of Babylon. Sennacherib enacted further campaigns against the Chaldeans and chased them to Elam, where he sacked multiple cities.

But the back and forth continued, and in the absence of the Assyrian army, the King of Elam marched into Babylonia. Ashur-nadin-shumi was taken prisoner and transported back to Elam, where he was likely executed. The Assyrians met the Elamite-Babylonian forces at Nippur, which was called the Battle of the Diyala River. Sennacherib’s forces defeated the Elamite-Babylonians, but Babylon refused to surrender. In 690 BCE, Sennacherib razed Babylon to the ground.

According to historians, the well-established respect the Assyrians had maintained for Babylon was overruled by Sennacherib’s desire to avenge his son and heir, as well as his continued frustrations with a city-state that needed to be re-conquered time and time again. While Assyrian troops customarily participated in iconoclastic attacks and kidnapped religious idols in other regions, they had never done this in Babylon due to their shared religious beliefs. But Sennacherib himself recorded the Assyrian attacks on temples and religious iconography and stated that he “devastated,” “burned,” and “dumped” the remains into water.

Sennacherib’s destruction of Babylon raised deep concerns in Assyria. The king attempted to justify his actions through a myth that put Marduk on trial by the principal Assyrian god, Assur. He added further insult to Babylon when he declared that Assur was now the deity at the center of Babylonian New Year celebrations, identified Babylon with the destructive goddess Tiamat, and connected himself with Marduk.

Unsurprisingly, this generated an unshakeable hatred among the remaining Babylonians. Sennacherib was later murdered by his eldest son Arda-Mulissu, who had been heir but was unexpectedly replaced with his younger brother Esarhaddon. Esarhaddon assumed the throne and executed all the conspirators while Babylonians celebrated Sennacherib’s death, describing it as a divine act of the gods.

Medo-Babylonian Conquest of Assyria

After his father’s controversial reign and his own complicated ascendancy, Esarhaddon was left paranoid about who to trust in court and the potential wrath of the gods. Therefore, the Assyrian king was dedicated to the reconstruction of Babylon after his father had left it in ruins. His successors continued his restorative program. But it would seem that after centuries of subjugation, Babylon would have the last laugh.

Ashurbanipal is typically named the last great king of Assyria and after he died in 631 BCE, Assyria’s fortunes changed significantly. Conspiracies erupted in the Assyrian court as Ashurbanipal’s son and named heir, Ashur-etil-ilani, was met with resistance. Despite Ashur-etil-ilani squashing his opposition, he died unexpectedly after just four years. His brother stood to inherit the throne, but he too faced hostility.

The Assyrian vassal king in Babylonia, Kandalanu, died in 627 BCE and Babylon rebelled against Assyrian control yet again. Nabopolassar was crowned King of Babylon in 626 BCE and King Sinsharishkun of Assyria responded by launching attacks in Northern Babylonia. At the same time, many Assyrian vassals, including Elam, stopped paying taxes to Assyria. Moreover, an unnamed Assyrian general rebelled against Sinsharishkun, which meant the king’s men had to leave Babylon to face the potential usurper. By 620 BCE, Nabopolassar had secured his sovereignty over the whole of Babylonia, while Assyria was dealt consistent blows from rebelling territories. The Medes then got involved and sacked Assur, the Assyrian cultural capital. Nabopolassar arrived on the scene during the looting. The Babylonians and the Medes created the Anti-Assyrian pact and Nabopolassar’s son, Nebuchadnezzar, married a Median princess.

Next, the Babylonians and the Medes took Nineveh, another key Assyrian city and it is thought that Sinsharishkun died in the battle. By this point, the Assyrian Empire had effectively dissolved. Ashur-uballit II became the new Assyrian King, but a formal coronation could not be held as it had always taken place in Assur, which remained in the hands of the Assyrian enemies. Ashur-uballit II was crowned in Harran, but his title “Son of the King” indicates that the Assyrians expected the traditional coronation at Assur would take place later.

The Siege of Harran in 609 BCE signaled the end of Assyria altogether and Ashur-uballit II retreated into the desert. The deposed Assyrian king returned just three months later with Egyptian support, but was forced to retreat again. He probably died shortly after. The establishment of the Neo-Babylonian Empire is accredited to the ascension of Nabopolassar to power. The succession of his son, Nebuchadnezzar II, ushered in a new period of Babylonian prosperity and imperialism.

Conclusions

Across a thousand years of largely shared history, Assyria and Babylon engaged in back-and-forth political affairs. Typically, the Assyrians utilized their refined military tactics to subjugate Babylon, the culturally more established state, which gave the Assyrian state credibility. However, the Assyrians shared the same deities because they were ruled by Babylonians early in their history, and even earlier still, both Assyria and Babylon were ruled by the Akkadians and Sumerians.

Thus, the Assyrians actively withheld from the same levels of persecution and re-settlement of defeated people that they used elsewhere. This created a problem whereby the Babylonians experienced greater freedoms and therefore possessed greater opportunities to rebel, which they consistently capitalized on.

Assyria and Babylon went through periods where their relations were more harmonious, usually after the Assyrians had made some sort of political arrangement post-conquest. The reign of Sennacherib and his merciless sack of Babylon cemented the Babylonian’s loathing of their Assyrian overlords. Nabopolassar’s ascension, the subsequent resurgence of Babylonian autonomy, and the ruthless assault on all of Assyria’s dominant cities can easily be seen as an act of vengeance.