Decolonization, much like colonization, is a complex and extremely diverse process. So are the strategies adopted by non-state actors and grassroots movements to achieve it, particularly in the three decades following the end of the Second World War. Depending on the actors involved, decolonization has taken different forms. In many cases, due to long-standing power imbalances, colonial subjects lacked the economic and military means to counter colonial forces and resorted to asymmetric warfare strategies, such as guerrilla warfare, sabotage, and civil disobedience, as well as art and literature, to counter the economic, cultural and linguistic hegemony of the colonizer.

Big Nations Losing Small Wars

The term “asymmetrical warfare” dates back to the 1970s, when Andrew J.R. Mack first used it—he used the term “asymmetric conflicts,” to be precise—in his article Why Big Nations Lose Small Wars: The Politics of Asymmetric Conflict.

The year was 1975. The Vietnam War was in its final throes and dozens of former colonies in Asia and Africa had managed to gain independence—in some cases after years of violent armed struggle. These anti-colonial uprisings represented what Mack calls “a radical break with the past”; in little less than three decades they shattered the assumption, cemented by millennia of warfare, that “conventional military superiority necessarily prevails in war.” They showed the world that insurgents, as Mack calls them, could win against a militarily superior power through protracted guerrilla warfare and the manipulation of foreign public opinion.

The term asymmetrical warfare describes a specific type of war, an atypical conflict between two unequal belligerents who differ in size, resources, and military capabilities. In an effort to wear down the opponent, the less powerful group—traditionally less likely to emerge victorious—manages to withstand the military impact of the more powerful group by resorting to prolonged guerrilla warfare and a variety of tactics ranging from ambush to hijackings and sabotage, from kidnappings to cutting communication lines to prevent the enemy from calling backup. Indeed, “guerrilla” is the Spanish term for “little war.”

Historically, insurgents in colonial countries have managed to weaken their opponents, despite being less heavily armed, by creating a situation of military and economic stalemate, which eventually causes the opponents to withdraw. Mack calls it strategy “the progressive attrition of their opponents’ political capability to wage war.”

This was the case with French troops (and settlers) in Algeria during the Algerian War of Independence and, of course, with American troops in Vietnam. The Vietnam War, Mack argues, “has demonstrated how, under certain conditions, the theatre of war extends well beyond the battlefield to encompass the polity and social institutions of the external power,” and that the psychological effects of war on public opinion are as crucial to victory as military victories on the ground. The Vietnam War, Mack continues, can be seen “as having been fought on two fronts—one bloody and indecisive in the forests and mountains of Indochina, the other essentially nonviolent—but ultimately more decisive—within the polity and social institutions of the United States.”

Guerrilla Tactics

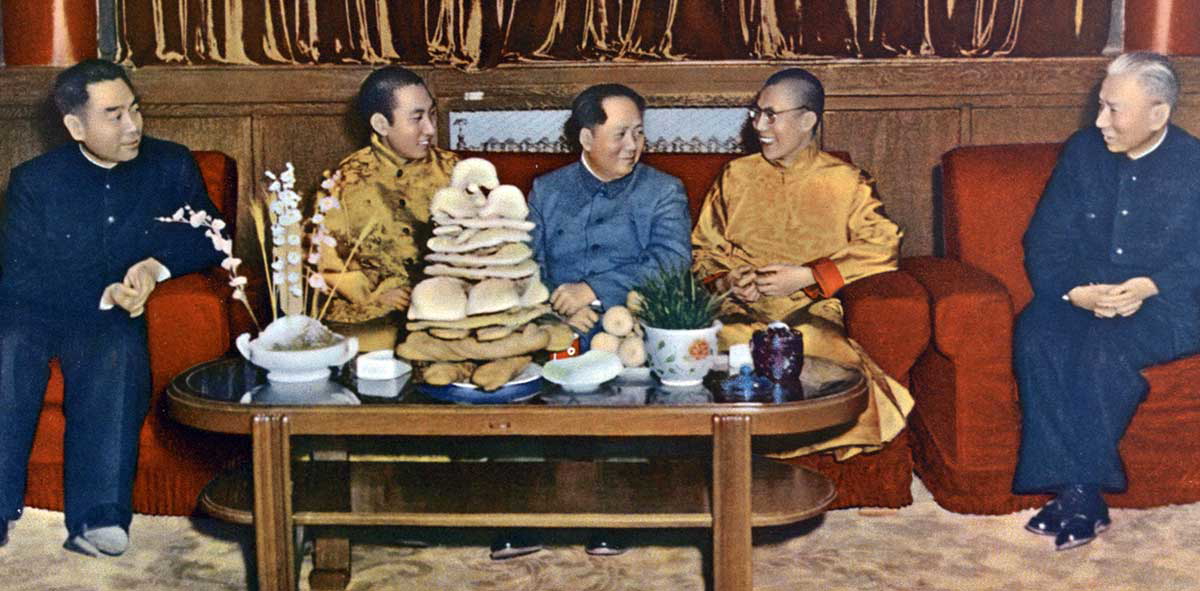

The first name that should come to mind when discussing guerrilla tactics is that of Mao Zedong (1893-1976). In his On Guerrilla Warfare (1937), he defined guerrilla warfare not as an independent, self-standing form of struggle, but as “one step in the total war, one aspect of the revolutionary struggle.” Guerrilla warfare, he believed, is the “inevitable result of the clash between oppressor and oppressed when the latter reach the limits of endurance.”

Guerrilla tactics, Mao argues, can only work if they’re a mixture of careful but quick decision-making, surprise, vigilance, and, of course, deception, if they’re aimed at destroying the enemy’s will and political (and social) ability to continue the struggle. In essence, guerrilla tactics work if they succeed in becoming a deterrent to the occupying power from deploying more troops. But what are the essential tactics at the heart of guerrilla warfare?

In On Guerrilla Warfare, Mao provides a manual of action that every guerrilla fighter should follow when fighting a seemingly stronger enemy—“harass him when he stops; strike him when he is weary; pursue him when he withdraws. In guerrilla strategy, the enemy’s rear, flanks, and other vulnerable spots are his vital points, and there he must be harassed, attacked, dispersed, exhausted and annihilated.”

Guerrilla tactics and strategies vary in their level of violence, from the assassination and/or kidnapping of government officials and civilians to the ambushing of troops, military convoys, and patrols. They may include feigned retreats, the use of booby traps, car bombs, and grenades, and the destruction (and sabotage) of military equipment, office buildings, police stations, power lines, air bases, bridges, and any other infrastructure controlled by the invading force. It was by resorting to these tactics that so many former colonies managed to shake off colonial rule in the three decades that followed the end of the Second World War. This was how to quote Mack’s famous title, big nations have lost small wars.

How Art Challenges Cultural Hegemony

“If Africans do not tell their own stories,” Ousmane Sembène, one of Africa’s most beloved filmmakers and writers, once famously said, “Africa will soon disappear.” A few years later, in 2018, the Aboriginal Australian writer Alexis Wright told the crowd gathered for the Melbourne Writers Festival: “The questions I have when thinking about Australian literature are often about how we dig from this country’s blood-stained earth. Do we have the heart, mind and soul, or feel we have the responsibility to reach this point of respect and trust, to dig into the oldest continent with the oldest living culture on Earth?”

The novels, short stories, and films of Ousmane Sembène (1923-2007) introduce foreign readers and moviegoers to the social, racial, and economic oppression of the French colonial government as experienced by Senegalese men and women. They portray the reality lived by thousands of Africans as seen through their own eyes, rather than those of French colonial officials or European settlers.

In North Africa Assia Djebar (1936-2015) introduced foreign readers to the role of women in her native Algeria as she, an Algerian woman of Chenouas Berber descent, saw it. Her books, written between the late 1950s and the early 2000s, illuminate the (often violent) evolution of Algerian society from a colony to an independent country.

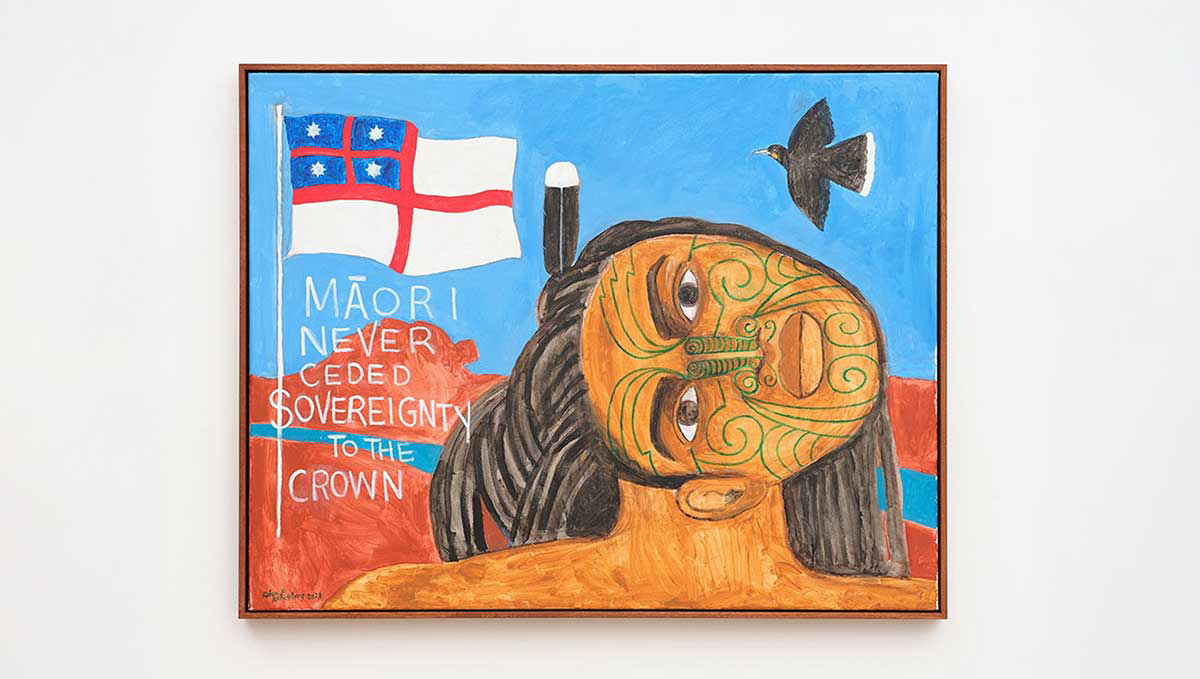

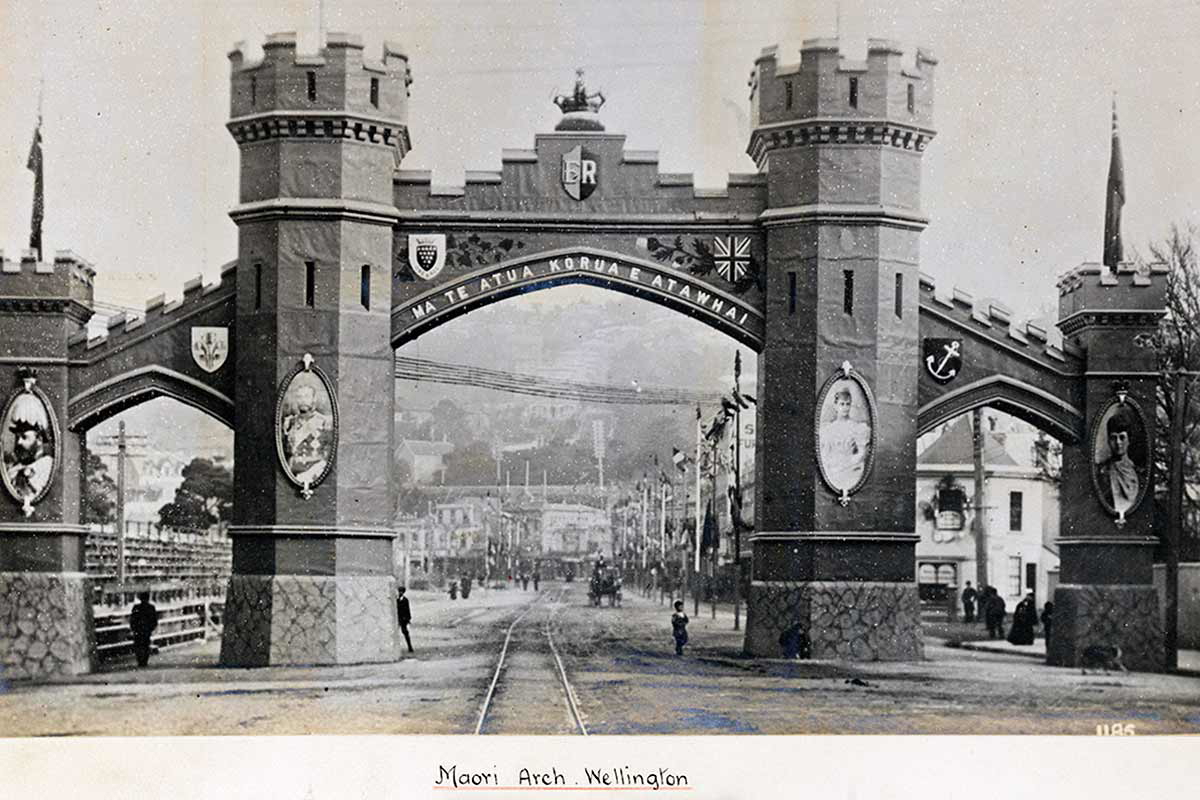

Thousands of miles away, on the opposite side of the world, a book was published in the mid-1980s, at the height of what critics have called the Māori Renaissance. The book is called Potiki. Its author is Patricia Grace, a New Zealander woman from Wellington / Te Whanganui-a-Tara, and the descendants of three major Māori tribes, the Ngāti Toa, Te Āti Awa, and the Ngāti Raukawa. The intertwining stories at the heart of Potiki do more than just address the issues that continue to affect Aotearoa/New Zealand society: they are a window into a unique worldview, too often misunderstood by non-Māori, that is finally reclaiming its right to exist and be heard.

Especially in post-colonial countries, the work of intellectuals—be they writers, musicians, painters, or filmmakers—extends beyond their individual endeavors. Working side by side with activists, they indirectly build solidary networks that extend far beyond national borders.

Intellectuals do—peacefully—what guerrilla fighters do indirectly when trapping the enemy in a protracted battle: by asking questions and cautiously suggesting the path that politics should take to address existing inequalities, they prevent anyone not directly involved from looking away. Assia Djebar, Ousmane Sembène, Alexis Wright, Patricia Grace, and many others show us that there is more to the road to decolonization than guerrilla warfare. Novels, poetry, music, theater, and cinema, all have a role to play in overturning narratives that are in many cases the product and the legacy of colonialism.

In her Boisbouvier Oration, Wright addresses the founding dilemma of her country, Australia, which was first created as a British penal colony through the deliberate oppression of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders. “What do we make,” she asks, “of the foundation stories millennia in age, that have survived since ancient times through the care and responsibilities of the custodians of these stories? Do we know what these stories can mean for Australian literature, or to the literatures of the world? Or how we can give stronger roots to our literature? Or how can we, in our relationships with each other, being people of many different backgrounds and cultures, make great literature here?” Her words, though rooted in the reality of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, suggest the existence of a thread connecting individual and collective acts of resistance and cultural resurgence in former colonies around the world.

Language as an Anti-Colonial Tool

In 1934, the French government passed the infamous Laval Decree, which essentially prevented African filmmakers living in French colonies from producing and directing films in their own countries. At the time, cinema was still the prerogative of European and Western culture—and, in Senegal, as well as in other French colonies, a tool of oppression, a vehicle for European propaganda, and cultural and linguistic hegemony.

In Assia Djebar’s books, for example, the French language comes across as the colonial imposition that it was, relegating to second place the languages spoken by the local population, namely, Arabic and Berber (or Tamazight). In Senegal, after winning the prestigious French Prix Jean Vigo for his first feature film, La Noire de… (1966)—Black Girl, in English—Ousmane Sembène went on to direct and produce a series of films in his native Wolof language, the language spoken by thousands of people in Senegal, southern Mauritania, and the Republic of the Gambia.

The fact that Sembène, the son of a fisherman from Ziguinchor in southern Senegal, decided (and was able to) in the 1960s, shortly after Senegal’s independence, pick up a camera and make his own films in the language of his people, portraying them not as caricatures but as complex, full-fledged characters, was revolutionary in itself. The fact that he did it in an African language was groundbreaking. And a sign that the times were changing.

In Aotearoa/New Zealand, Patricia Grace is just one of the many Māori writers who are finally using the language of their ancestors alongside English in their novels. The Māori language, te reo Māori, only gained official status in 1987 when the Parliament of New Zealand passed the Māori Language Act. In the same year, Witi Ihimaera published what is now his best-known work, The Whale Rider, although his first collection of short stories, Pounamu, Pounamu, had been published more than a decade earlier, in 1972.

In his 2014 memoir, evocatively titled Māori Boy, he writes that at the age of 15, he decided to write about what it meant for him to be Māori after being forced by his teacher to read a short story (which he found insulting) by renowned Australian writer, Douglas Stewart (1913-1985), about an encounter between a Pākehā young man and a group of Māori: “I said to myself that I was going to write a book about Māori people, not just because it had to be done but because I needed to unpoison the stories already written about Māori.”

Through a careful blend of English and Māori terms, Patricia Grace and Witi Ihimaera’s works echo the efforts of other Māori activists and scholars to affirm the integrity and complexity of the Māori language (and, by extension, Māori culture), not as a subordinate to English, but as its rightful equal.

In Ireland, particularly in the years leading up to the Irish War of Independence, the (Irish) Gaelic served as a bridge between violent and non-violent resistance to British occupation. The use of Irish instead of English was a way of asserting Irish identity and the legitimacy of any Irish-born man or woman living in an independent and sovereign country, a way of reclaiming Irish culture outside the sphere of British cultural hegemony.

Indeed, the aim of the Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League, in English), founded in 1893, was to promote the Irish language—in Ireland and abroad—and to “de-anglicize Ireland.” At the same time, Gaelic was often used in coded conversations between Irish volunteers, both inside and outside British prisons, a shield behind which Irish prisoners could hide, as most British administrators and soldiers could not understand Irish. In Northern Ireland, Gaelic continues to be a marker of identity for the Catholic community.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, empires crumbled. While some former colonies managed to negotiate their way to independence, in other countries the anti-colonial struggle left thousands of dead. Armed organizations resorted to forms of asymmetric warfare in their effort to force the colonizer to withdraw.

Guerrilla tactics—from ambushes to feigned retreats, from kidnappings to sabotage—were often accompanied by another crucial asymmetric strategy, the less violent but no less effective attack on the colonial government’s economy. This grassroots economic resistance often took the form of boycotts and mass strikes, as it happened in Senegal and India. In some cases, local traders refused to pay taxes. In others, local workers on strike occupied railway lines and key transport routes, disrupting and slowing down colonial exports.

Armed struggle and non-violent forms of resistance often went hand in hand with a movement of cultural resistance and the celebration of Indigenous and local languages. In Algeria, for example, alongside the guerrilla war waged by the National Liberation Front (FLN) against French rule, writers such as Assia Djebar wrote about the experiences of Algerian women in what can be seen as an act of cultural resistance against the stereotypical and self-serving ideas many Europeans of the time had about Algerian culture.

“This seems to be where the power and purpose of literature is,” Alexis Wright once said of her native Australia, “still at the introductory stage, drawing from the surface layer of stories of our two-and-something centuries, but growing with a lot more truth telling, reimagining and rewriting history, and now, with far more of our stories coming from different cultural backgrounds.”