On New Year’s Eve 192 CE, the Roman Empire’s Golden Age, almost a century of political tranquility, came to an abrupt and violent end. A protracted period of civil war followed as various men sought to fill the void left by the imperial dynasty that died with Commodus. This competition between rival emperors ended in February 197 CE at Lugdunum in Gaul, with the largest battle in Roman history.

The Build-Up to the Battle of Lugdunum: Civil War

On New Year’s Eve 192 CE, a cabal of Roman senators and other conspirators gathered the courage to finally strike against a tyrant. The victim of the plot was the emperor Commodus. Famous to modern audiences as the villain of the Hollywood blockbuster Gladiator, he had slowly descended into megalomania for the latter part of his 12-year reign. He gave increasingly free reign to his cruelty, while his delusions of grandeur went far beyond an obsession with the gladiatorial arena. Reputedly, he was even planning to rename Rome after himself. The imperial capital would henceforth be known as Commodiana!

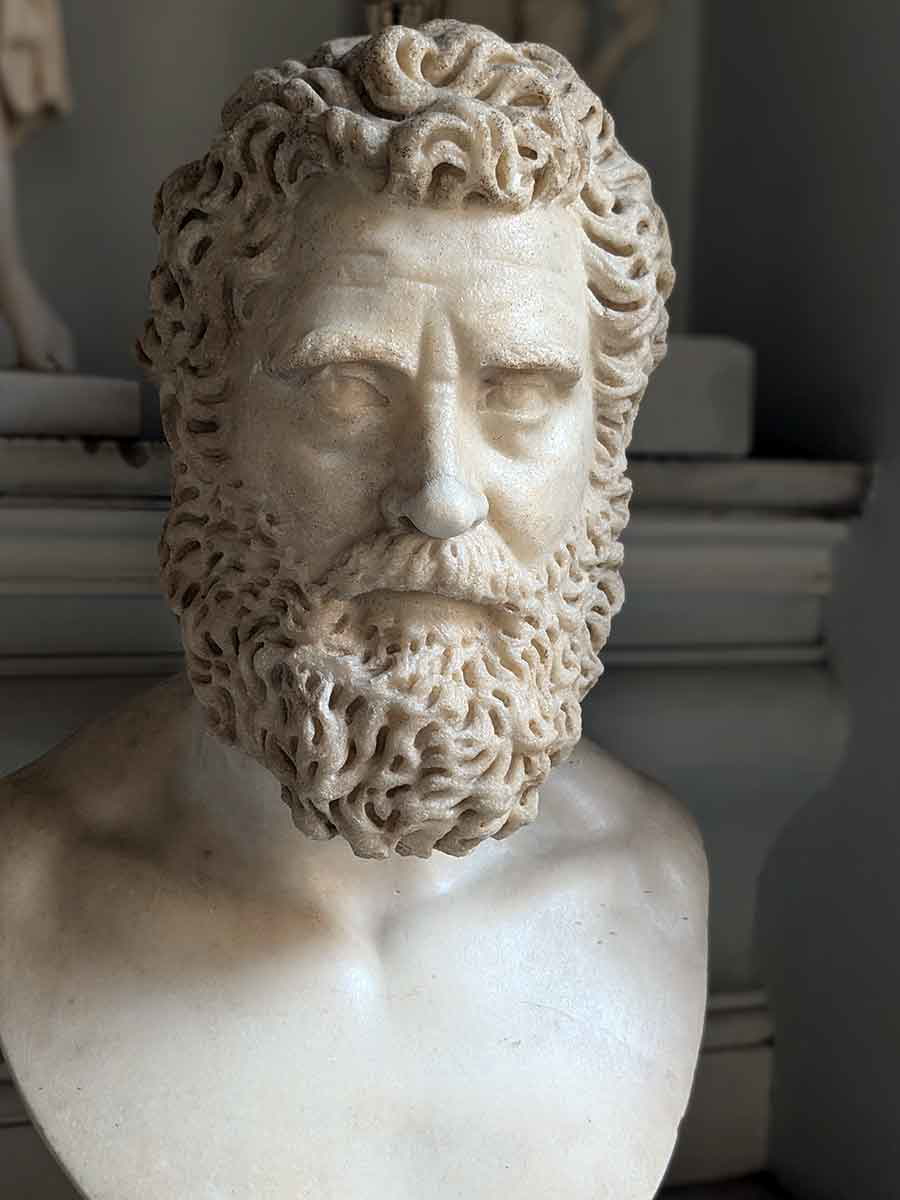

On December 31, drunk and bloated as he wallowed in his bath, Commodus was poisoned. Unfortunately for the conspirators, the emperor survived and managed to purge his body of the toxins. However, in his weakened state, he was easy pickings. Narcissus, a powerful young wrestler who was kept around Commodus’ court, was dispatched by the emperor’s wife to go and finish the job. The wrestler strangled Commodus. With his death, Rome’s so-called Golden Age came to an end. This was almost a century of political peace and stability that coincided with the reigns of the Antonine Emperors: Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius. Commodus, Marcus Aurelius’ son, had no heirs. With the dynasty at an end, there was a political vacuum.

Early on the morning of New Year’s Day, Rome awakened to a new emperor. The elder statesman, Publius Helvius Pertinax, was recognised by his fellow senators. While he may have had the support of his former colleagues, he was not a popular choice among other demographics in Rome, not least the Praetorian Guards. The imperial bodyguards, accustomed to lavish pay and an easy life under Commodus, did not take kindly to the new emperor’s tighter control of their pay and privileges. Within three months, Pertinax was murdered. The guards stormed the imperial palace and slaughtered the old man.

Rivals Turn Allies: Septimius Severus and Clodius Albinus

With the death of Pertinax, Rome descended into political chaos. The Praetorian Guards retreated into their camp, fearful of retribution. There, they were entreated by two men, Titus Sulpicianus and Didius Julianus. Aware, following Pertinax’s premature end, of the need to have the support of the Praetorians if they wished to rule, the two men offered the soldiers increasingly higher sums of money.

This donative or cash payment was a typical gift offered by new emperors upon their accession. Despite this, the competitive character of this exchange—between the guards, Sulpicianus, and Julianus—was rather grubby. The whole fiasco was characterized as an auction for the empire by the historians who described it. In the end, Julianus’ “bid” of 25,000 sesterces for each guardsman was enough to trump Sulpicianus’ resources. Julianus was welcomed into the camp and proclaimed emperor. However, any positive mood would be short-lived: Rome was on course for civil war.

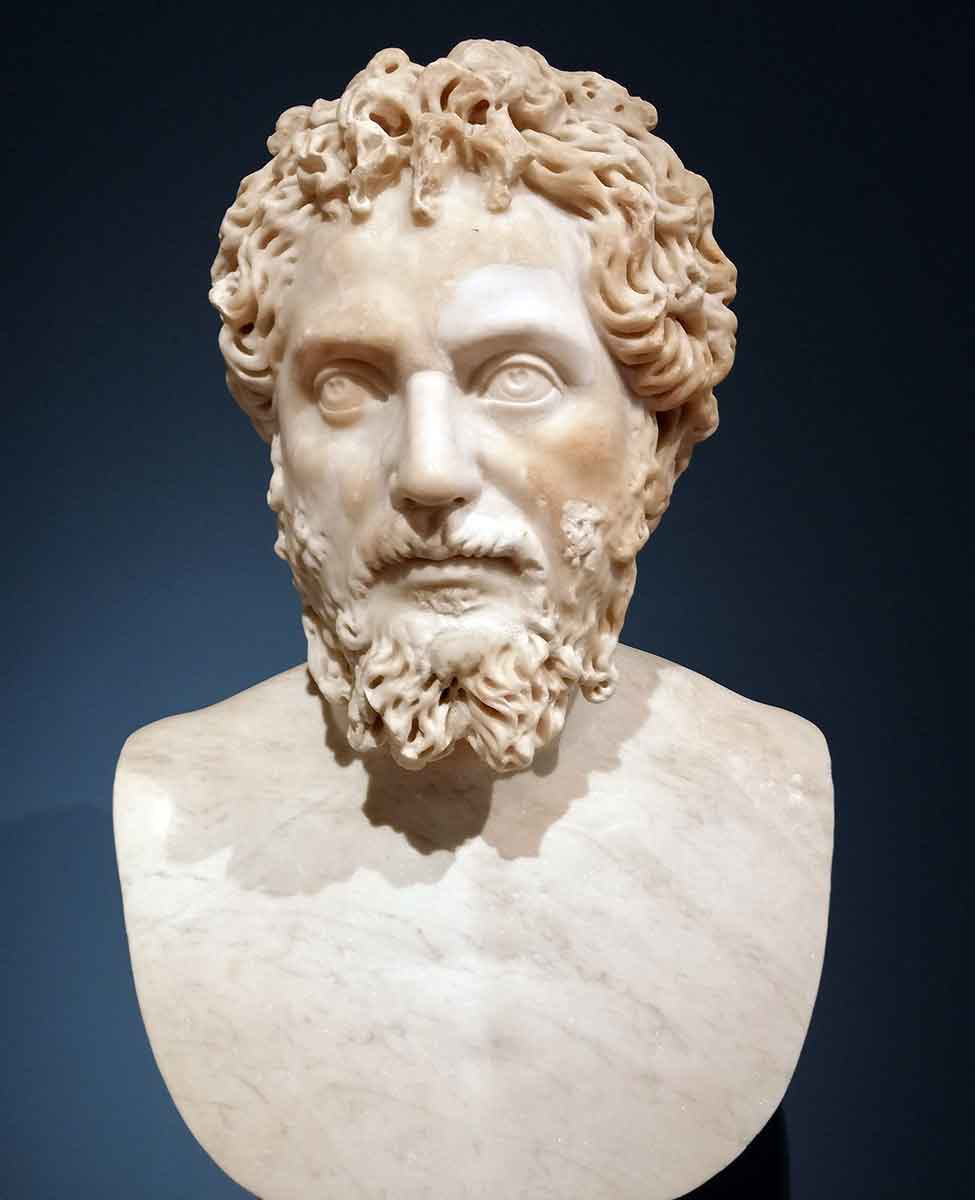

While Julianus was in control of Rome, a number of rival candidates for imperial power emerged around the empire. In the east, the governor of Syria, Pescennius Niger, was acclaimed by his soldiers. He had previously been the subject of impassioned public pleas by the urban plebs in the Circus Maximus. In the west, the governor of Britain, Clodius Albinus, was also declared emperor. Between these two rivals, there was a third, Septimius Severus, the governor of Pannonia. Of all of the imperial rivals, Severus was recognized as the shrewdest, not only by his contemporaries, but also later, by Machiavelli, who described the man as embodying the courage of a lion and the cunning of a fox. The governor of Pannonia knew that once Julianus was dealt with, there would be a conflict between the surviving rivals. Severus’ approach was an ingenious form of divide and conquer.

First, he marched on Rome, where he promptly dispatched Julianus and the avaricious Praetorians who had “sold” the empire. With the symbolic heart of the empire secured, Severus then made overtures to Clodius Albinus. An alliance between the two was formed, with Severus recognising Clodius as his junior partner and “heir.” Crucially, however, no formal adoption took place. Nevertheless, the bond was cemented by Albinus using “Severus” as part of his nomenclature. Epigraphic evidence from this period identifies the governor as Severus’ partner in power, such as from a dedication at Ostia for the safe return of Augustus Severus and his Caesar Albinus. With Italy and the western provinces under his control, Severus turned his attention to Niger in the east.

Notwithstanding a protracted siege of the city of Byzantium, which remained loyal to Niger, Severus was able to defeat his eastern rival over the course of 193-194. The decisive battle was fought at Issus in late 194, the same battleground on which Alexander the Great had defeated the Persians centuries before.

A brief campaign followed thereafter, waged against the eastern territories that had allied with Niger, including the Arabians and Adiabenes. Known as the First Parthian War, the strategic goals are hard to ascertain. Instead, Cassius Dio’s caustic remark that war was simply a means for Severus to gain further glory and wealth is likely close to the mark. Significantly, the campaign also allowed Severus to integrate Niger’s defeated forces into his own ranks. He would need all the fighting men he could muster for the battles that lay ahead.

Battleground: Lugdunum in the Roman Empire

The city of Lugdunum, modern Lyon, was located in southern Gaul. Originally a Gallic settlement, a Roman city had been founded on the site in 43 BCE by Lucius Munatius Plancus. He was a seasoned political maneuverer who was able to skillfully shift allegiances during the civil wars at the end of the Republic.

Lugdunum rapidly became the administrative capital of the province of Roman Gaul. Its importance came, in part, from its position at the confluence of four major arterial roads, which connected it not only to important cities in Gaul, such as Massilia and Aquitania, but also Italy and the imperial frontiers in Germany. The city’s importance was confirmed in 15 BCE when it was de facto recognized as a commercial hub. A mint was established at Lugdunum, replacing existing operations in Hispania. It was not until 64 CE, during the reign of Nero, that gold and silver coin production was moved back to Rome itself.

Reflecting the city’s strategic and financial importance, Lugdunum had a close relationship with numerous imperial figures throughout its history. During the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the city hosted Agrippa, Drusus, Tiberius, and Germanicus, who had all served in Lugdunum during their military careers. In fact, Claudius, the son of Drusus and a future emperor, was born in Lugdunum in 10 BCE. The relationship with members of the imperial family greatly benefitted the city, and the population boomed.

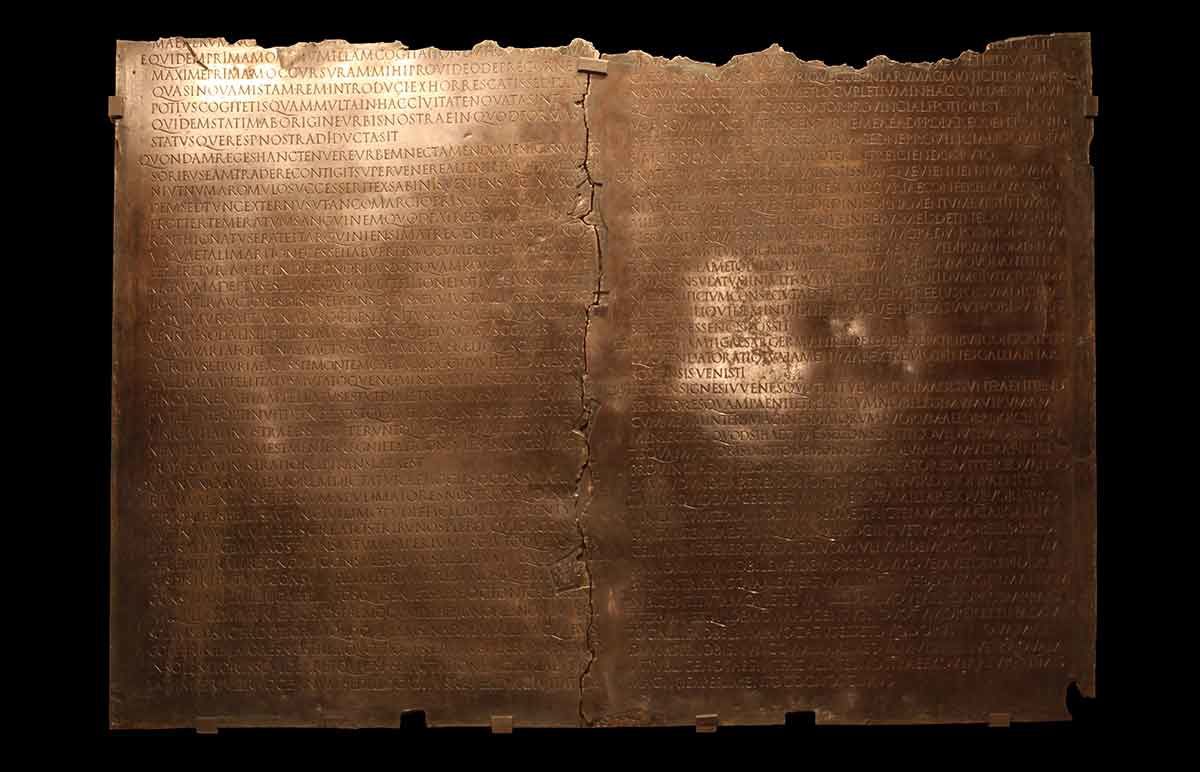

Fresh drinking water was poured into the city through four aqueducts, which supplied homes and public baths. Residents of the city were entertained by spectacles at the “Amphitheatre of the Three Gauls,” the first amphitheater constructed in Gaul. The importance of the city was confirmed by Claudius’ so-called “Lyon Tablet.” This document records a speech delivered to the senate in 48 CE, also recorded in Tacitus’ Annals, which proposed to allow monied, landed citizens from Gaul to enter the senate.

Heirs and Spares: The Break Between Severus and Albinus

Having defeated Pescennius Niger, allowing him to flood his ranks with soldiers and his coffers with loot, Severus was now primed to confront his sole remaining rival for power. His eastern successes put paid to any notion of his allegiance with Albinus enduring for the long term. By late 196, it was clear to many observers that war was looming on the horizon. During the Saturnalia festivities, it was reported that the urban populace gave full voice to their laments at the coming violence. The senators, however, stayed quiet. To be seen to back the wrong rival at this juncture could have fatal consequences.

The definitive catalyst for the break was Severus’ reneging on his initial deal with Albinus. The former governor of Britain was usurped as the imperial heir by Severus’ own son, Lucius Septimius Bassianus, who would go on to be known more commonly by his nickname, Caracalla. Severus’ son, who was born in Lugdunum in 187 while his father was posted there as the provincial governor, was barely ten years old at the time of his elevation to Caesar. He would, therefore, have had no real political authority. The move was, however, loaded with symbolic significance. Declaring Caracalla as his heir was an assertion of Severus’ dynastic intentions. The empire would now be ruled by the men of the Severan family.

Moreover, Severus had Caracalla’s actual name changed from Bassianus to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus. This connected his own family to that of the former ruling dynasty of Marcus Aurelius and his predecessors. This endowed Severus’ family with added prestige, which may have been an attempt to counter Albinus’ superior aristocracy, and it was an assertion of imperial continuity and stability. Severus’ regime not only looked forward but also anchored itself in the stability of the former regimes, which were so celebrated.

Albinus, who, despite the change in his nomenclature to become a “Severan,” had not been formally adopted, was excluded from this. In a speech delivered to his soldiers, Severus urged them to declare Albinus a hostis publicus, an enemy of the state, an act which was usually a senatorial prerogative. With the assent of the soldiers, war was now inevitable. The stage was set for the final confrontation at Lugdunum.

The Battle of Lugdunum: Severus’ Triumph

Albinus struck first. Having been recognized by his own forces as emperor, he gathered legions from Britannia and marched them south through Gaul, establishing his headquarters at Lugdunum. His choice reiterates the city’s strategic importance in the Roman period. There, Albinus was joined by Lucius Novius Rufus, the governor of Hispania, and the legion he had under his command.

From Lugdunum, Albinus attacked the Germanic legions who were loyal to Severus and led by the governor Virius Lupus. Despite some successes, Albinus’ assaults were not enough to break the resolve of Lupus’ forces, who remained loyal to the Severan cause. Further encroachment south toward Italy was not feasible for Albinus at this time, as Severus had reinforced the Alpine passes. This brought Severus enough time to amass his forces along the Danube River and head west, marching into Gaul.

It was during these initial skirmishes that one of the most extraordinary figures from Roman history emerged. Although he was only a schoolmaster, Numerianus evidently felt compelled to join the Severan cause. Masquerading as a senator sent by Severus to raise an army, Numerianus gathered a small group of men in Gaul and undertook a series of daring raids, including defeating a group of Albinus’ cavalry. Unaware of the false identity himself, Severus, who believed Numerianus to be a senator, commended the schoolmaster-turned-guerilla and ordered him to continue.

There followed Numerianus’ most striking success. In a raid on Albinus’ forces, he captured and delivered to Severus a sum of 70 million sesterces. In the aftermath of the war, Numerianus met with Severus, the new emperor, and was offered wealth and status. The humble schoolmaster politely rejected these privileges. Instead, he opted for a quiet life in the country and a small allowance from the emperor in recognition of his services. Recorded only in Cassius Dio’s narrative, the episode of Numerianus appears to be a throwback to some of the more virtuous figures from Rome’s earliest history.

An initial skirmish between Severus’ and Albinus’ forces at Tinurtium, modern Tournus, was ultimately inconclusive, although Severus would claim the day. Instead, having fallen back, Albinus and his men drew up at Lugdunum and, on February 19, 197, prepared to fight the largest battle in Roman history. The exact numbers of combatants are hard to establish with surety, although Dio records 150,000 men on each side. Both Severus and Albinus were present among their soldiers to lead them on the day.

The battle itself was a tense affair. As Severus’ right wing broke through and devastated Albinus’ camps, so too did Severus’ left wing suffer terrible losses against Albinus’ right. In fact, in his efforts to salvage his forces from the massacre unfolding on his left wing, Severus himself was unseated from his horse and nearly killed. He displayed his courage, however, tearing off his cavalry cloak and brandishing his sword to rally his panicked men.

The decisive maneuver of the day was led by Laetus, the commander of Severus’ cavalry. He was initially reluctant to join the fighting in the interest of self-preservation and with an eye to possibly securing power for himself, according to Dio and Herodian. When the cavalry saw the tide begin to turn, their charge into Albinus’ forces broke the resolve of the army. Severus was victorious.

After Lugdunum: The Severan Empire

The Battle of Lugdunum exacted a heavy price with many thousands of Roman dead on each side. Men and horses were strewn across the battleground, while their blood poured into the rivers. According to Dio, Albinus fled the battleground and sought shelter in a house beside the Rhone. Realizing his desperate plight, he committed suicide. Severus, presented with the body of his defeated rival, gave free rein to his rage. The corpse was desecrated, and then decapitated, and the head of Albinus was dispatched to Rome to be displayed publicly.

The supporters of Albinus in Rome fared little better. The emperor’s rage was made known in dispatches, with Severus even going so far as to praise the cruelty of Sulla, whose own victory in the civil war had been followed by senatorial bloodletting in the notorious proscriptions. Upon Severus’ return to Rome, while the people were rewarded with donatives and celebrations, many senators were executed and their wealth seized.

Assured of his power for now, Severus set about consolidating the status of his nascent dynasty. A Second Parthian War was fought. Celebrated on the Arch of Septimius Severus in the Forum Romanum, the war won more glory, more riches, and more territory for the empire. To confirm his commitment to imperial stability, he himself claimed Marcus Aurelius as a father, further consolidating links to the previous dynasty. Elsewhere, Severus modeled himself on Augustus, and around the imperial capital, great building works were undertaken, including the restoration of the Pantheon, and the construction of the enigmatic Septizodium, a now-lost colossal nymphaeum at the foot of the Palatine hill. However, despite his best efforts, the stability Severus sought would prove elusive. His two sons, Caracalla and Geta, were marked for succession, but the brothers had a fraught relationship. The Severan Empire would soon begin to splinter.