The Sassanid Empire, founded in 224 CE, started by defeating the Parthians. Calling themselves Eranshahr or “Empire of the Iranians”, at their height, they reigned from Pakistan to the Levant. Yet by the 630s, decades of conflict with the Byzantines, Arabs, and internal revolts left the Empire exhausted.

The wars had taken their toll. The upstart yet deadly Muslim armies occupied half of the Empire by 636. Even the imperial capital Ctesiphon fell in 637. The Empire’s young King Yazdegerd III sat on an uneasy throne.

Their Ascendant Opponent

While the Sassanids faltered, the Arabs remained energetic. Following the Prophet’s death in 632, the Rashidun Caliphate’s armies expanded Islam’s reach.

All of Arabia fell by 632 CE. The conquest of Egypt, the Levant, and sections of the Sassanid Empire would follow. Their armies decisively won with new tactics and their opponents’ exhaustion. Being religiously cohesive provided a purpose and identity, unlike the multi-ethnic empires they faced.

Around 637 CE, Arab armies pushed the Sassanids back into central Iran. The stage now stood for the Battle of Nahavand.

Nahavand’s Critical Importance

Besides being a military and administrative center, Nahavand (near modern Hamadan) lay astride critical routes. Roads to Mesopotamia and Bactria connected here. Nahavand controlled access to the Zagros foothills (the Sassanid homeland) and the remaining strongholds.

The Eve of Battle

The inevitable high-stakes clash finally occurred in 642. For King Yazdigerd III, this battle was a make-or-break deal. Defeat meant the end of the Empire and its Zoroastrian faith. A victory would mean political stability.

For the Arabs, a victory meant occupying the remainder of Persia. Islam’s steady march could continue.

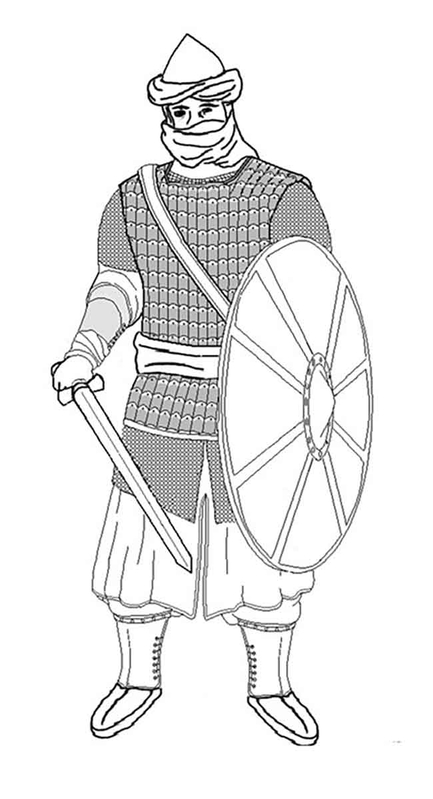

An All Out Effort

The late summer or early fall of 642 CE saw the culmination of the Sassanid-Arab conflict. Since the disasters of 637, a low-grade war had simmered. But now, King Yazdegerd III called up his army. Sources vary, but upwards of 150,000 assembled, a mixed force of professionals, militia, and farmers. The King and Zoroastrian priests hailed this fight as a do-or-die. At a minimum, the Sassanids sought to halt the Arab advance.

The Rashidun Caliphate’s army consisted of approximately 30,000 soldiers. Inferior in numbers, these soldiers were now seasoned, mobile veterans. Plus, fresh victories and religious zeal bolstered their confidence. This Calphiate army, commanded by the experienced Nu’man ibn Muqarrin, now marched to Nahavand.

The Battle Commences

The Sassanid commander, Firuzan, knew of the approaching Arab army and prepared defenses in the hills around Nahavand. Firuzan understood his position as the settlement sat in a valley. Neither side anticipated how long the fighting would take.

Part One: Deception and Pursuit

The Arabs carefully scouted as they approached Nahavand; Nu’man knew of the superior Sassanid strength and fortifications. A head-on attack would be disastrous. His army repeatedly skirmished with the enemy, sizing up responses and terrain. Upon reaching the area, Nu’man decided to use subterfuge.

The Arabs camped in the open valley within sight of the Sassanid defenses-a tempting target. Also, some sources claim that the Arabs managed to convince their enemy that their morale was low. The Sassanid commander, Firuzan, remained cautious, aware of disasters like al-Qadisiyyah.

With the knowledge that the Sassanids watched the Caliphate army, Nu’man began his deception. He ordered the camp to be abandoned. Despite looking chaotic, the pullback remained orderly. Nu’man’s disciplined troops headed out of the valley, hoping to goad the Sassanids.

Initially, Firuzan kept his army in their fortified heights. Against the battle-hardened Arabs, he knew his predominantly peasant army’s stood little chance. But with a change of mind, Firuzan broke camp.

Part Two: A Snap Decision’s Price

The Sassanid army hotly pursued the Arabs from the valley. But being raw troops, their cohesion suffered. Once down from the heights and in the valley, Nu’man’s forces struck. Concealed cavalry hit from the sides, and infantry cut the Sassanid line of retreat. Here, the Sassanid numbers turned against them. Unable to maneuver in a cramped space, the Rashidun Caliphate army utterly destroyed the Imperial army. Thousands died, including Firuzan, in the chaos. The Arab leader Nu’man perished too, struck by a Persian arrow.

Part Three: The Aftermath and Collapse

With this crushing defeat, effective Sassanid resistance ended. Nahavand fell with immense spoils into Arab hands. Persia’s Islamic transformation now began. Yazdegerd would be assassinated in 651. So great was the Arab victory that the Rashidun Caliphate named the battle Fath al-Futuh, or “Victory of Victories.”