On the Ides of March, 44 BCE, Julius Caesar was assassinated. Punctured by as many as 23 stab wounds, the death of the dictator threw the Roman world into civil war once more. On one side, the “Liberators.” Led by Brutus and Cassius, these men conspired to kill Caesar ostensibly to restore the Republic. On the other side was a fragile alliance of Caesar’s allies, Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian. The climactic battle for control of Rome would take place at Philippi in October 42 BCE.

Background to Philippi: Caesar’s Assassination

In 49 BCE, Julius Caesar had crossed the Rubicon, a shallow river in northeastern Italy. This seemingly innocuous act was a catalyst for the collapse of the Roman Republic, which had endured since 509 BCE. His march across the Rubicon with the armies that had conquered Gaul was tantamount to a declaration of war.

The civil war that followed would last four years and rage right across the vast expanses of the empire, including Greece, Egypt, and Hispania. Upon his return to Rome, Caesar was appointed dictator perpetuo (dictator in perpetuity). Rome had had dictators before, but never one in perpetuity. To some senators, Caesar was becoming a monarch in all but name. A king was antithetical to the values of the Republic, and a conspiracy was soon hatched to topple Caesar.

On the morning of the Ides of March (15th) 44 BCE, Calpurnia, Caesar’s wife, begged the dictator not to attend to his business that day. She had been plagued by visions of her husband’s death, according to Plutarch. For a moment, he hesitated. His wife was not usually one for “womanish superstition,” the later biographer noted. In the end, however, he departed, and his fate was sealed.

At the Senate meeting, hosted at the Curia (Senate House) located in the Theatre of Pompey, the conspirators, numbering around 60 or 70 senators, began to crowd around Caesar. Ostensibly, they sought Caesar’s approval of a petition. In reality, they closed around him to deliver the fatal blows. The dictator was stabbed at least 23 times by the conspirators. After the conspirators fled, Caesar’s allies mobilized. Rome was heading for civil war.

For the Republic: The Liberators at Philippi

According to Appian, a wax statue of Caesar was erected in the Forum. The posthumous depiction of the slain dictator included the 23 stab wounds he had sustained at the hands of the so-called Liberators. There was public uproar at the death of the popular general. A large mob gathered and set the Curia on fire.

Although they had not envisaged it, by killing Caesar, the Liberators had exacerbated the cracks forming in the Republic’s political structures. Popular with the people, Caesar’s assassination was taken as an abhorrent abuse of senatorial power. The political outlook for the Liberators was further worsened when Mark Antony, several days after the assassination, managed to persuade the Senate to ensure that Caesar’s political appointments would remain valid.

The furious reaction to the news of Caesar’s murder, coupled with the reaffirmation of his political appointments, effectively forced the Liberators out of Italy. In a similar move to Pompey and the anti-Caesarian party of just a few years previously, the Liberators fled the peninsula.

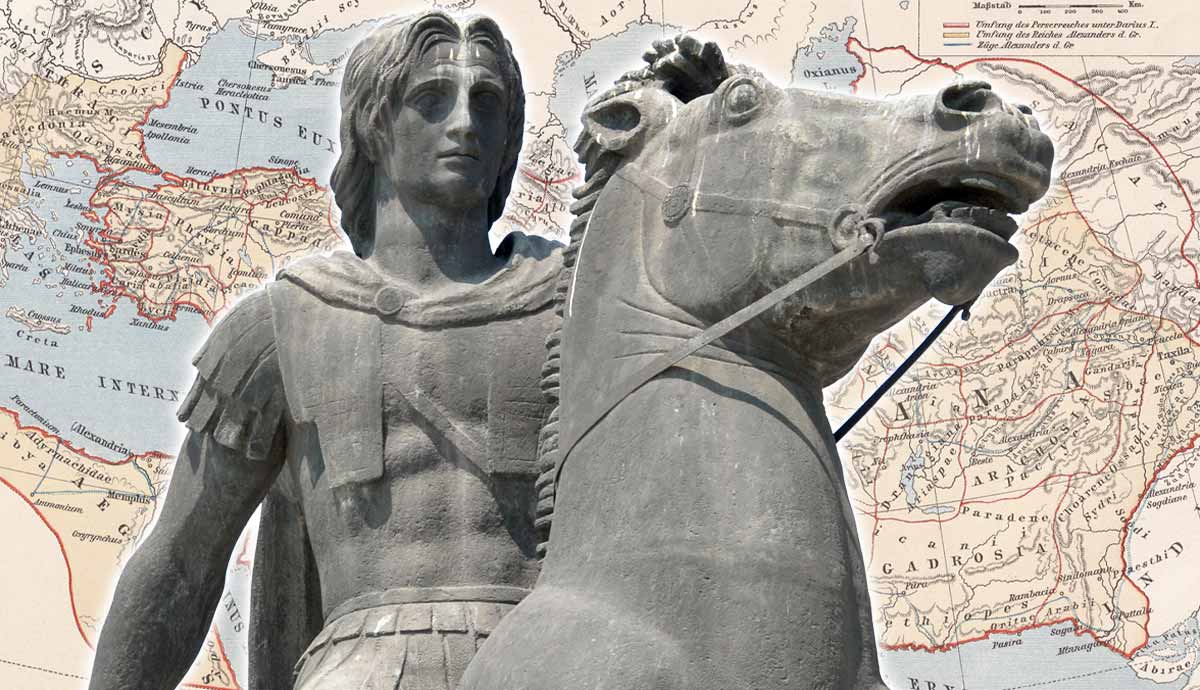

They gathered their forces in Greece and mobilized the forces of the eastern provinces. At sea, the Liberators could count on the fleet of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. A distant relative of the future emperor Nero, Ahenobarbus was effective in harrying the enemies of the Liberators. Led by Brutus and Cassius, the Republican forces had by this time established themselves on the high ground, just slightly to the west of the city of Philippi in Macedonia.

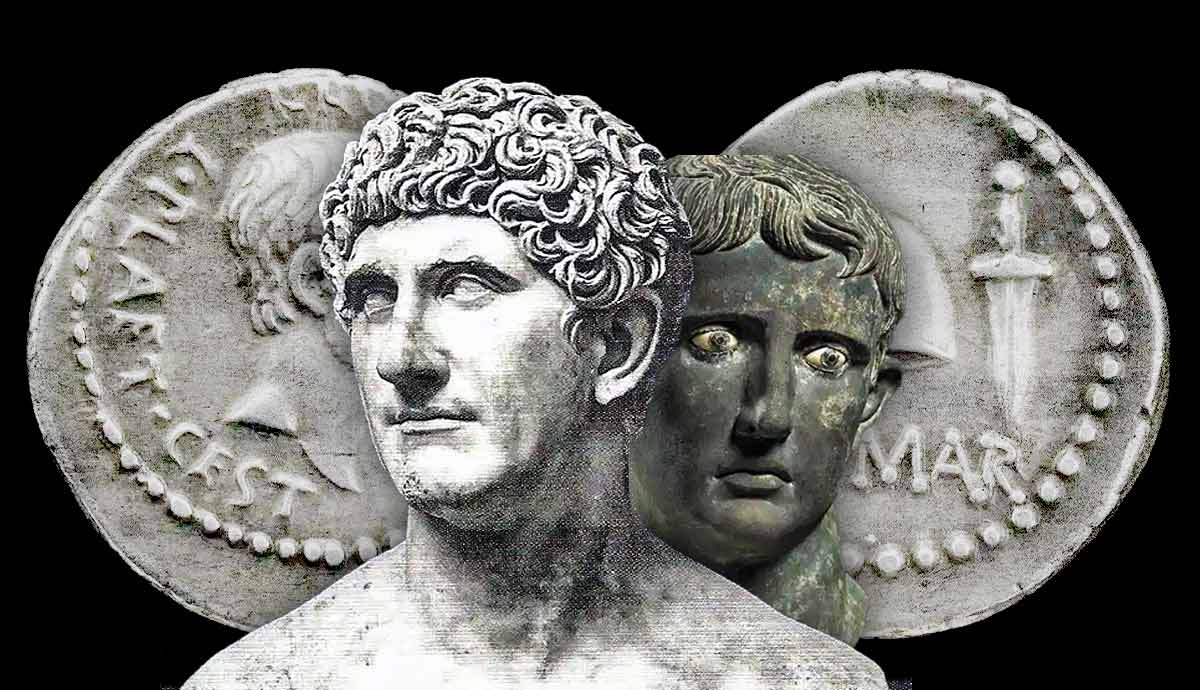

An Uneasy Alliance: The Second Triumvirate

Arrayed against the forces of the Liberators massing in the east was the Second Triumvirate. This uneasy alliance comprised Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Mark Antony, and Gaius Octavian, Caesar’s great-nephew adopted as his son and heir in his will. The alliance had been established in 43 BCE, when Octavian, as consul, travelled north from Rome to establish a treaty with Antony. The relationship between the two had been tense as Octavian’s adoption by Caesar was a tremendous blow to Antony’s own plans for supremacy. Their new alliance was confirmed by marriage. Octavian would marry Antony’s step-daughter, Clodia, as a mark of good faith between the two men.

Assured in their partnership, at least for now, the Second Triumvirate could turn its attention to a war of vengeance against the Liberators. In all, some forty legions were massed. They also sought to consolidate control of Italy and ensure they had sufficient resources for war. To do so, they turned to the terror tactic of proscriptions. These lists of enemies, used so infamously during Sulla’s dictatorship, named around 300 senators as wanted men. If caught, they would be executed and their property and wealth seized. Concessions were made by each triumvir to show support for their union. This was bad news for one of the most famous of all Roman senators, Cicero. Despite holding him in high regard, Octavian was compelled to acquiesce to Antony’s proscribing of Cicero. The former consul had been openly critical of Antony for too long, excoriating him in his Philippics, named after the famous orations of Demosthenes against Philip II of Macedon several centuries earlier.

The First Battle of Philippi: Cassius’ End

Perhaps unfairly, Lepidus is sometimes characterised as a rather “beige” figure in the tumultuous decades of the end of the Roman Republic. Whether or not such a view is historically valid, it certainly is not helped by his absence from some of the more decisive events of the period. For instance, it was decided by the triumvirs that Lepidus would remain in Italy when, in 42 BCE, Antony and Octavian set sail for Greece. They were accompanied by 28 legions, their best fighting men. Ashore, the forces were divided. An advance party of eight legions was sent ahead, the remainder divided between Antony and Octavian. While Antony was able to follow the scouts, Octavian’s forces were temporarily delayed by the young man’s ill health, a recurring issue he faced throughout his life. They eventually regrouped to face the forces of the Liberators at Philippi.

Although Antony did his best to tempt the Liberators into an engagement, Brutus and Cassius remained reluctant to leave their fortified position. Antony was eventually able to bring Cassius to battle, but only by attempting a dangerous maneuver of leading his men through the marshes to the south of the Liberators’ position.

While Antony’s forces engaged those of Cassius, Brutus led his forces against Octavian’s legions. They took the young man’s forces completely by surprise. Octavian’s legions lost three standards and were driven in disarray right back to their camp, which was captured by Brutus’ forces. Fortunately for the triumvirs, Antony was having significantly more success. Cassius’ fortifications had been utterly demolished and his camp overrun. Although the battle so far had been something of an even contest, Cassius was unaware of this. He believed that his ally, Brutus, had suffered a devastating defeat, and so he ordered his freedman, Pindarus, to kill him. It was a crushing blow to the morale of the Liberators.

Brutus’ Defeat: The Second Battle of Philippi

Despite the death of one of their leaders, all was not lost for the Liberators. At the same time that the first engagement was underway, their naval forces had obliterated a fleet of reinforcements and supplies en route to the triumvir army. However, Brutus lacked the strategic nous of his fallen comrade, and the Liberators were unable to capitalize on the advantage won at sea. The military experience, which Brutus lacked, proved a decisive factor against the forces of Octavian and the battle-hardened Antony. Slowly but surely, the creeping advance of the triumvir forces stretched the battlelines of Brutus’ army ever thinner.

Dangerously close to being cut off, despite his naval superiority, Brutus had no choice but to engage the triumvirs on the battlefield. Plutarch’s account of the Battle of Philippi describes how Brutus’ initial advance was successful. However, on the other side of his army, the triumvir forces punched through the lines of his overextended legions. Although it began gradually, the Republican forces were flanked, eroding both men and their resolve. The envelopment was so complete that the legions under Octavian’s command were able to capture Brutus’ encampment. The triumvir’s victory was total, and Brutus was left with no option but to flee.

With a small force of just four legions, the Liberator fled. In the wilderness about Philippi, Brutus fell upon his sword. Although Brutus allegedly faced his end with courage, his body was treated gruesomely. Suetonius describes how Octavian had the body decapitated, and the head dispatched to Rome, where it was to be displayed before a statue of Caesar.

After the Battle of Philippi: Octavian Against Antony

The victory of Antony and Octavian at Philippi was final. What was left of the Liberators’ army was rounded up, and around 14,000 men were enrolled in the triumvir’s army. The fate of many of the leading aristocrats who had sided with the Liberators was less positive. Many died, either in battle or by their own hand. This included Marcus Porcius Cato (the son of Cato the Younger), as well as Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus, the father of Livia, Octavian’s future wife. Marcus would have had no idea that, through his daughter, his descendants would go on to shape the course of Roman history.

Despite the overwhelming victory achieved by the triumvirs, there was to be no peace. Tensions between Octavian and Antony, a constant undercurrent of the triumviral relationship, flared when they had no shared enemy to be tempered against. It became increasingly clear that the fight for control of Rome was not yet over.

The decisive battle took place at sea. In 31 BCE, the forces of Octavian would meet the combined fleet of Antony and Cleopatra, the Ptolemaic Queen of Egypt, at Actium. Octavian, with the help of Agrippa, would triumph. Control of the Roman world was his. Years later, a monument was set up by Octavian, who was then known as Augustus, to commemorate Philippi, the first step on his journey to ruling the entire Empire. The Res Gestae of Augustus simply recorded: “I sent into exile the murderers of my father [Julius Caesar]… when they made war upon the Republic, I twice defeated them in battle.”