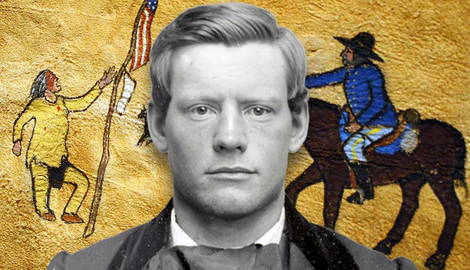

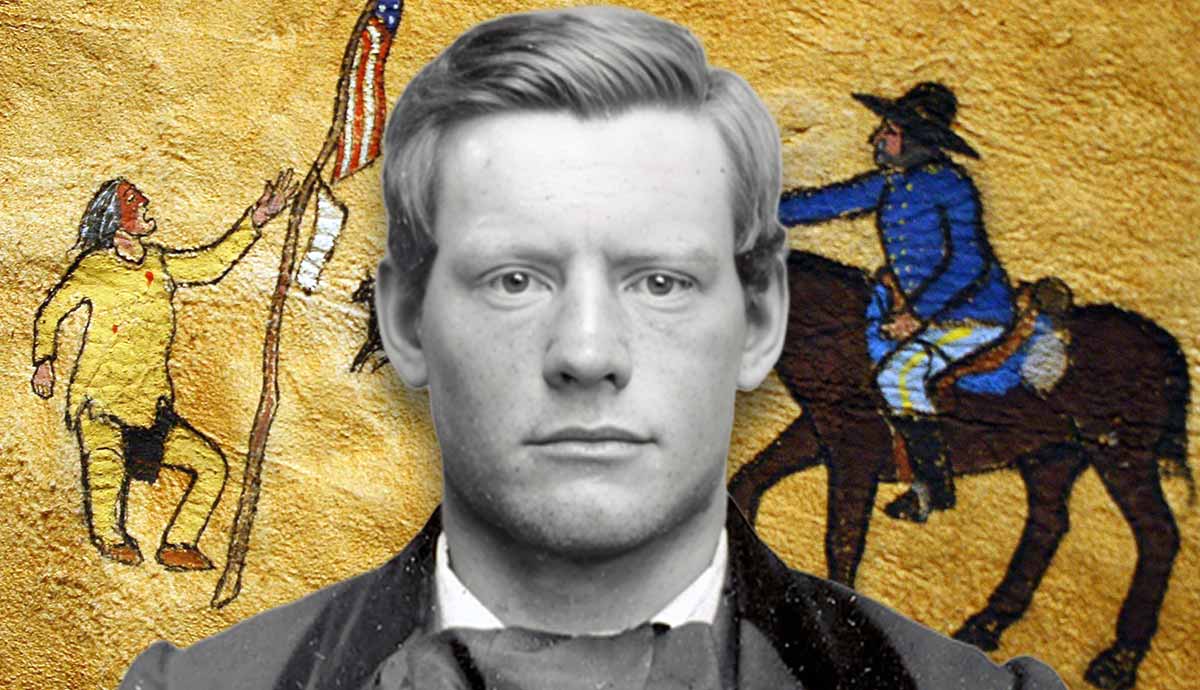

Silas Soule was a member of the United States military when the army was undergoing a crisis of conscience. First facing the issue of slavery with his American brethren in the US Civil War and later tasked with subduing the American Indian, Soule was dedicated to his assignments but never ignored his ethics. An example of what was later termed a “whistleblower,” Soule sacrificed his safety in pursuit of human rights. He paid for his efforts with his life but is remembered by many as a hero who represents what it means to do the right thing.

An Early Life of Activism

Born July 26, 1838, in Bath, Maine, Silas Stillman Soule was the second son of Amasa and Sophia Soule. Amasa was dedicated to the abolitionist cause from its early days in the United States. When Silas was just a teenager, his father moved to Kansas, along with his older brother, to support anti-slavery causes there. Silas became the man of the house, working factory jobs to help support his mother and younger siblings.

The next year, the remainder of the Soule family moved to Kansas, where their home became a stop for the Underground Railroad. Silas was involved as an escort for the Railroad and, along with his father, became involved in the events that later became known as “Bleeding Kansas.” The Soule men were members of the Jayhawkers, an abolitionist militia group. Silas became an expert in hit-and-run guerilla warfare tactics, utilizing carbines that had been sent from pro-abolition groups in New England in crates marked “Bibles.” Still just a teen, Silas became a member of the “Jayhawker Ten,” also known as the “Immortal Ten” or “Terrible Ten.” These men were an elite militia group who conducted raids, liberated enslaved people, and freed jailed abolitionists. Silas was instrumental in the jail rescue of Dr. John Doy, a local physician and abolitionist who had been apprehended by pro-slavery advocates. With his “Kansas Bible” in tow, he even traveled to Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia, in 1859 as part of a group attempting to rescue followers of the recently executed John Brown.

After his time in West Virginia, Silas became frustrated and disillusioned with the Jayhawker cause. John Brown’s followers had refused to be rescued, preferring to instead be martyred for their crimes. Silas believed they should have kept fighting. In addition, the Jayhawker Ten had come under increased scrutiny after the events at Harper’s Ferry, and the Kansas authorities were looking for Silas. He decided to spend a year in Boston, where he worked as a printer and befriended poet Walt Whitman.

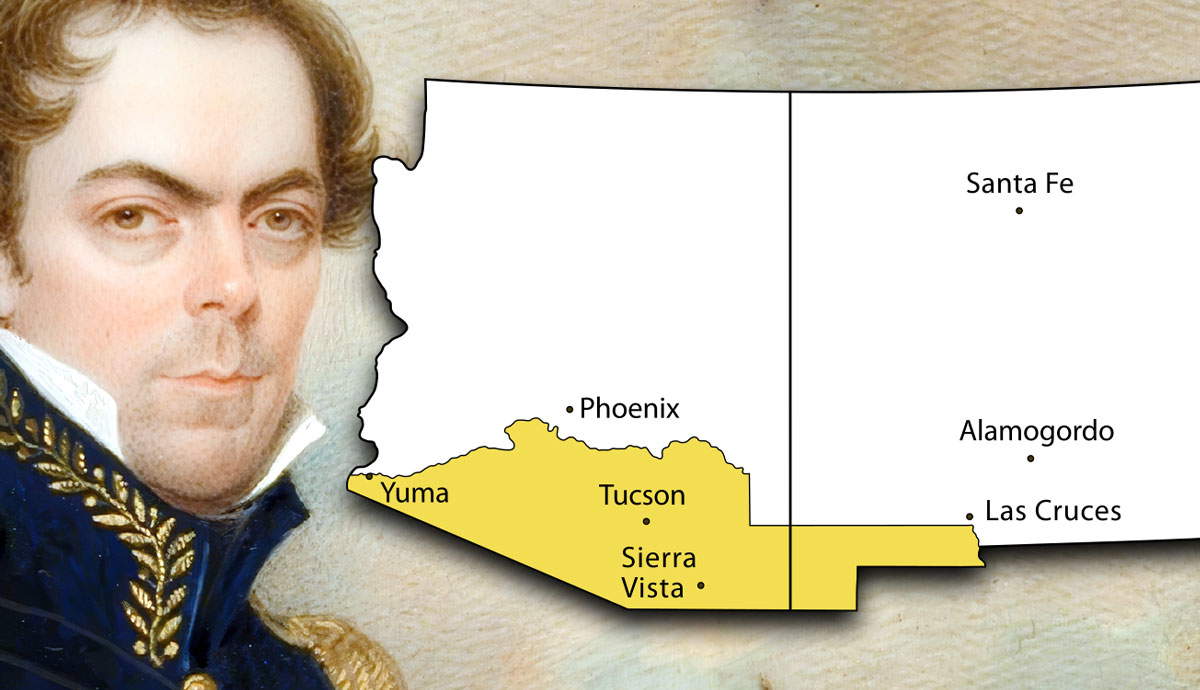

In 1860, Soule found that the allure of the gold fields was an irresistible temptation. With his brother William, he headed west to Colorado to make his fortune. While he was not a successful miner, Silas worked briefly as a blacksmith. When the Civil War broke out, Colorado, which was not yet a state, created a pro-Union volunteer army, the Colorado First Regiment. Silas Soule was one of its first volunteers. His militia experience allowed him to rise quickly through the ranks, and he was a first lieutenant at the age of 22. After the Battle of Glorietta Pass, where Silas’s regiment prevented the Confederate army from moving west, the Colorado First Regiment was welcomed as an official US cavalry unit.

A Different Focus for the Army

Silas proved his worth as an army officer, and his regimental leader, Colonel John Chivington, recognized his bravery on numerous occasions. He was eventually promoted to captain and was placed in charge of Fort Lyon. As the Civil War began to wind down, especially in the West, the army began to focus on another objective—assimilating America’s Indigenous peoples. Silas and his co-leader at Fort Lyon, Edward Wynkoop, believed that the local tribes should be treated with respect and fairness in these dealings, but they were in the minority among military officials. Soule and Wynkoop helped negotiate important early treaties with the Cheyenne and Arapaho people in Colorado.

A Horrific Massacre

On November 28, 1864, Colonel Chivington gathered his local regiments, including Company D, led by Soule, and ordered them to report. He claimed there had been word of a pending attack by Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors. As they approached the location, Silas realized that Chivington did not have accurate information about a supposed attack. The village in question was peaceful, settled near Sand Creek, and flying an American flag.

The village was led by Black Kettle, whom Silas had met with only two months ago at the Camp Weld peace conference. The camp was made up of a majority of women, children, and the elderly. Soule brazenly challenged his superior officer, arguing that the camp was largely unarmed and not hostile. He called Chivington a coward and murderer, and in return, Chivington threatened to hang Soule and take command of his company. Still, Silas refused to continue. He ordered his men against participating, threatening to outright shoot anyone who followed Chivington’s order to attack. While Soule’s regiment hung back, the remainder of Chivington’s companies moved forward and attacked.

Approximately 160 Cheyenne and Arapaho people were killed at Sand Creek, with about two-thirds of them believed to be women and children. Soule and his men were able to save a few. Not only did Chivington’s men kill, but they also committed atrocities such as scalping and mutilation. Soule recounted the chilling details of what he saw that day in a letter to Wynkoop on December 14. The correspondence included graphic and disturbing recollections, including, “I tell you, Ned, it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized.”

Meanwhile, Chivington was writing letters of his own. He let his superiors in Washington, DC, know that his Colorado cavalry had just completed a battle against “hostile Indians,” winning an effective victory for the United States. He also mentioned that he had been having trouble with one of his captains, Silas Soule, calling him “a greater friend to the Indians than the whites.” Chivington told army leaders he would be keeping a close eye on Soule.

Taking a Stand

Silas could not contend with what had happened at Sand Creek and how Chivington lauded the “victory.” In addition to contacting Wynkoop, he sent dispatches to his friend Walt Whitman and, most importantly, members of the US Congress. In January 1865, the War Department started an investigation into the army’s actions at Sand Creek.

Soule became one of the first to testify against Chivington as the inquest kicked off. He was threatened by those loyal to Chivington, but continued his work in supporting the investigation. Chivington retired from the army to avoid military court, and due to his impressive Civil War record, no criminal charges were brought against him. He had hoped to become involved in politics after his military service, but his new reputation as “The Butcher of Sand Creek” prevented these aspirations, and he never forgave Soule.

Silas Soule found brief happiness in the time after the massacre and investigation. He left the army at the end of his contract and took a job overseeing military police in Denver. He remained friends with Wynkoop, and the two frequented a saloon called Cobrely’s Halfway House. The middle daughter of the saloon owner caught Silas’ eye, and the two were married. His new wife, Hersa, was known for her intelligence, quick wit, and love of practical jokes. The two were married on April Fool’s Day, 1965.

On April 23, Silas and Hersa were walking home from visiting friends when shots rang out nearby. Silas, as part of his duties, felt obligated to investigate. He entered a nearby alley, walking right into a trap. He was shot and killed by two men who served under Chivington. Though the men were arrested, they later escaped custody and were never convicted for the murder. Rumors flew that Chivington hired the men to complete the job, but these were never proven.

A Quiet Legacy

While relatively little has been published about Silas Soule and his life in comparison to many contemporaries, some are still working to keep his memory alive today. In 1999, the Sand Creek Massacre Healing Run was initiated by Cheyenne and Arapaho people representing their descendants who were slaughtered at Sand Creek. The final day of the 180-mile event is dedicated to Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joe Cramer, who also provided affidavits about the events at Sand Creek. In 2013, Otto Braided Hair, a Northern Cheyenne and event organizer, stated in a speech to participants: “If not for them, there might not be any Cheyenne and Arapaho here today.”