After the Civil War ended, freedom came in name but not in practice for millions of formerly enslaved people. In Southern states, a new system quickly emerged to replace slavery: the Black Codes. These laws controlled where freedmen could live, how they worked, and what rights they had. The Black Codes exposed the South’s unwillingness to accept change and laid the groundwork for decades of racial segregation. For many African Americans, the end of slavery was just the beginning of a new kind of struggle.

A New System

The Black Codes were created immediately after the Civil War by Southern legislatures in 1865 and 1866, just months after the Confederacy surrendered. Their purpose was to combat the newly enacted 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution and to maintain white control in a world where slavery had just been outlawed. Mississippi and South Carolina were the first to pass them, and other former Confederate states followed. These laws varied by state but shared one goal: to limit the freedom of newly emancipated African Americans.

At their core, the Black Codes were an attempt to force freedmen back into a labor system that looked a lot like slavery. With the plantation economy reeling and the South needing workers, white lawmakers crafted policies that restricted mobility, access to land, and even basic civil rights. The codes were designed to ensure that Black people would remain poor, dependent, and under control.

In some states, African Americans couldn’t rent property outside of towns. In others, they were required to sign yearly labor contracts or face arrest. These laws accomplished their goal; for the next century, African Americans would be beholden to these laws, which returned them to an institution that many called “worse than slavery.”

Criminalizing Freedom

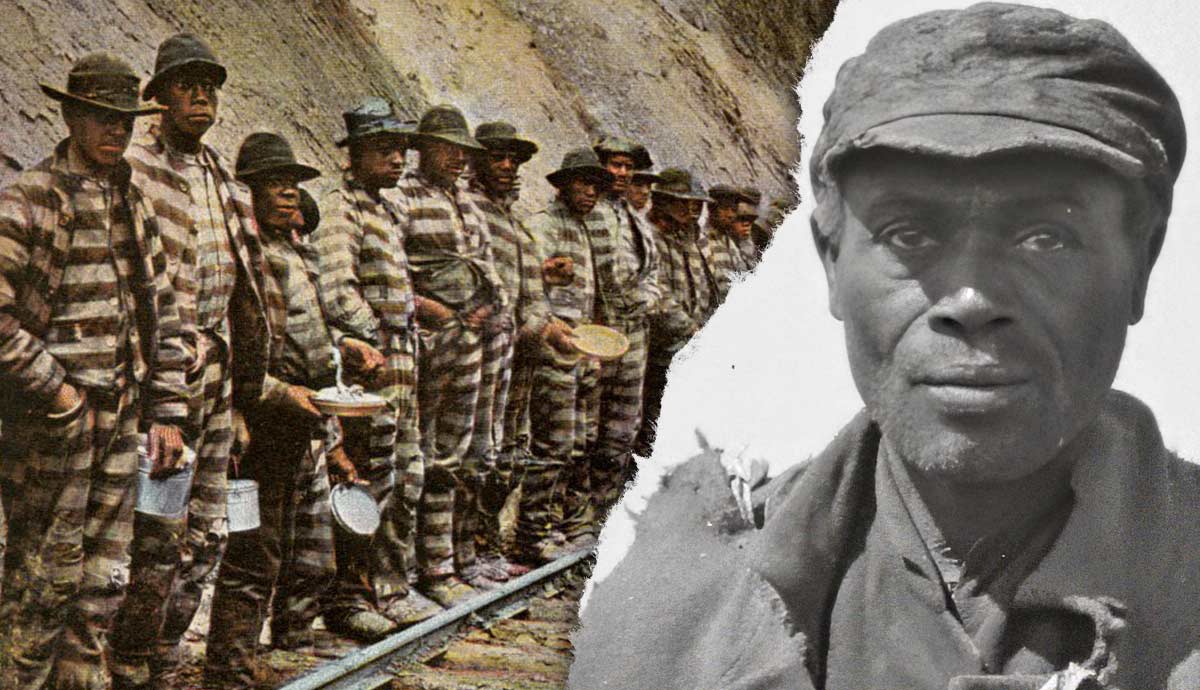

One of the most disturbing features of the Black Codes was how they criminalized everyday life for freedmen. Vagrancy laws were at the heart of this system. In many Southern states, if a Black person was unemployed (meaning they were not employed by a white male), homeless, or simply “loitering,” they could be arrested and fined. But since most newly freed people had little or no money, they couldn’t pay the fines.

If freedmen could not pay their fines, they would be sentenced to jail time in the state penitentiary for a determined period of time. States would lease out prisoners—mostly Black men—to private companies or plantation owners, who would pay the state for their labor. It was a money-making scheme that functioned like slavery, just with a paper trail.

The work was brutal, the treatment inhumane, and the system completely rigged. While slavery was inhumane, the post-emancipation treatment of freedmen as laborers was far more brutal. Employers had no incentive to protect the laborers because they didn’t own them—they were leased, disposable, and they had no monetary value to the business or plantation owner. The state made money, and white landowners got cheap labor.

The vagrancy laws were intentionally vague, giving sheriffs and judges enormous power to arrest freedmen for almost anything. Simply walking at night or not carrying proof of employment could land someone in jail. For many, emancipation quickly turned into slavery under a new name.

Controlling Freedmen

The Black Codes didn’t just police labor—they controlled where Black people could live, when they could travel, and what jobs they could take. In many towns, local ordinances prevented African Americans from renting or buying property outside designated areas. These early residential restrictions were precursors to later housing segregation laws.

Some codes required freedmen to have written permission to be in a town after dark. Others mandated that Black workers could only take jobs as field hands, domestic servants, or manual laborers. Skilled trades and better-paying jobs were often off limits.

The intent was to prevent economic mobility, keep freedmen in positions of subordination, and ensure the racial hierarchy of the Antebellum Era continued during the Post-Civil War years. Southern whites feared the political and social consequences of a free Black population with access to wealth or property. The Black Codes enforced that fear through legal boundaries.

Freedmen who tried to move or find better opportunities were labeled as “vagrants” or even “runaways.” In a time when freed men and women were traversing the country in search of their loved ones who had been sold away during slavery, the vagrancy laws presented a problem in uniting families. Law enforcement, too, worked hand-in-hand with employers to track down and punish those who resisted. Though slavery was over in name, the restrictions on movement and employment made freedom conditional.

Restoring White Control

At the heart of the Black Codes was a clear objective: rebuild the Southern economy to its former glory by exploiting black labor. Plantation owners had lost their enslaved workforce, but they still owned the land and needed a cheap workforce to ensure profits. The Black Codes gave them exactly what they needed, a legal route to exploit black labor for little to no wages.

Annual labor contracts were often required by law. If a Black worker left a job before the contract expired, they could be arrested and forced to return. Wages were low, conditions were harsh, and workers had almost no legal protection. The employer held all the power. Some laws even prohibited Black people from quitting without permission. In effect, these contracts bound them to the land just as slavery had. Landowners could also withhold pay until the end of the year, leaving workers with no income and no way to leave. Many were trapped in cycles of debt and dependency come harvest season.

Landowners often supplied workers with necessities, requiring the fees associated with their goods be repaid with interest come harvest season. Often, freedmen did not earn enough to pay back their debt, creating a higher rate the following year. This wasn’t a return to slavery, it was slavery’s evolution. The names had changed. The system hadn’t.

Congressional Action

The Black Codes didn’t go unnoticed. As word of their enforcement spread, Northern politicians made their feelings known. Many in the North had believed that the war’s end and the passage of the 13th Amendment would lead to real freedom. But the South’s swift creation of new restrictions proved the fight for freedom wasn’t over.

In response, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the first federal law to define citizenship and guarantee equal protection under the law regardless of race. The 14th Amendment, which followed shortly after, granted citizenship to all people born within the borders of the United States. This amendment was retroactive, meaning it applied to those who were born prior to the passage of the amendment.

Radical Republicans pushed for stricter Reconstruction policies, taking control of Southern state governments and nullifying the Black Codes. For a brief moment, it seemed like the tide had turned. African Americans began voting, holding office, and opening freedmen’s schools. But that moment was short-lived. White Southerners resisted these changes, and once federal troops were withdrawn in 1877 following the election of Rutherford B. Hayes in a controversial election, Southern states introduced new laws, Jim Crow, that continued the same systems.

The Building Blocks of Jim Crow

The Black Codes set the blueprint for the next century of racial discrimination in the South. But the ideas and intentions behind the Black Codes carried over into the Jim Crow Era. Segregated schools, voter suppression laws, and bans on interracial marriage were rooted in the same ideology as before, maintaining white supremacy.

Black Codes taught Southern lawmakers how to craft laws that sounded neutral but were designed to target Black people. They also showed local governments how to enforce inequality without ever mentioning race explicitly. The legacy of the Black Codes is long. Their influence can be seen in everything from housing discrimination to mass incarceration in today’s modern society. What began as a reaction to emancipation became a permanent feature of American law.

Defending Freedom

The Black Codes revealed the harsh truth that freedom, once granted, still had to be defended. The end of slavery didn’t end racism. It didn’t create equality. Instead, it sparked a backlash that used legal tools to recreate the social order that had existed under slavery. For African Americans, the years following emancipation were not a celebration, they were a continued struggle.

The Black Codes proved how quickly freedom could be undermined if it wasn’t protected by law and enforced by power. They also exposed the limits of federal authority in guaranteeing civil rights. Without consistent enforcement, state and local governments could dismantle progress one law at a time. But in the face of these challenges, freedmen and women built communities, opened schools, founded churches, and organized for political power. The Black Codes may have been designed to crush that spirit, but they also inspired generations of resistance. From Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement, the fight continued. The Black Codes remind us that slavery didn’t end with the passage of the 13th Amendment.