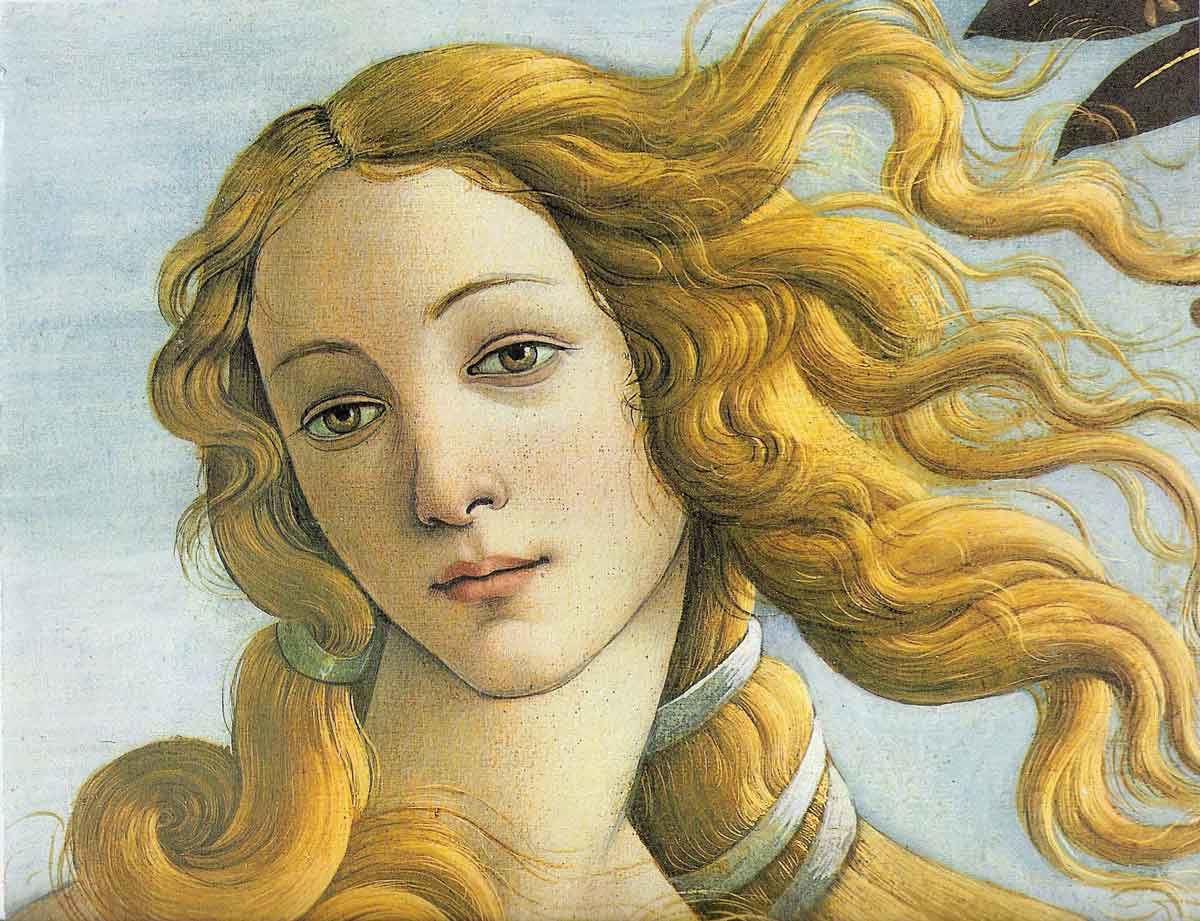

Botticelli’s Primavera is a timeless image. However, it is definitively tied to its direct context — that of the wedding of two members of prestigious Florentine families. The roots of its inspiration stretch far back into antique Roman poetry, specifically that of Ovid and Lucretius. Yet, it is the inspired visual imagination of Botticelli that transforms the textual narratives and their local details into a concerted, nuanced, and ultimately inexhaustible image — with help from a poet friend.

Botticelli’s Primavera

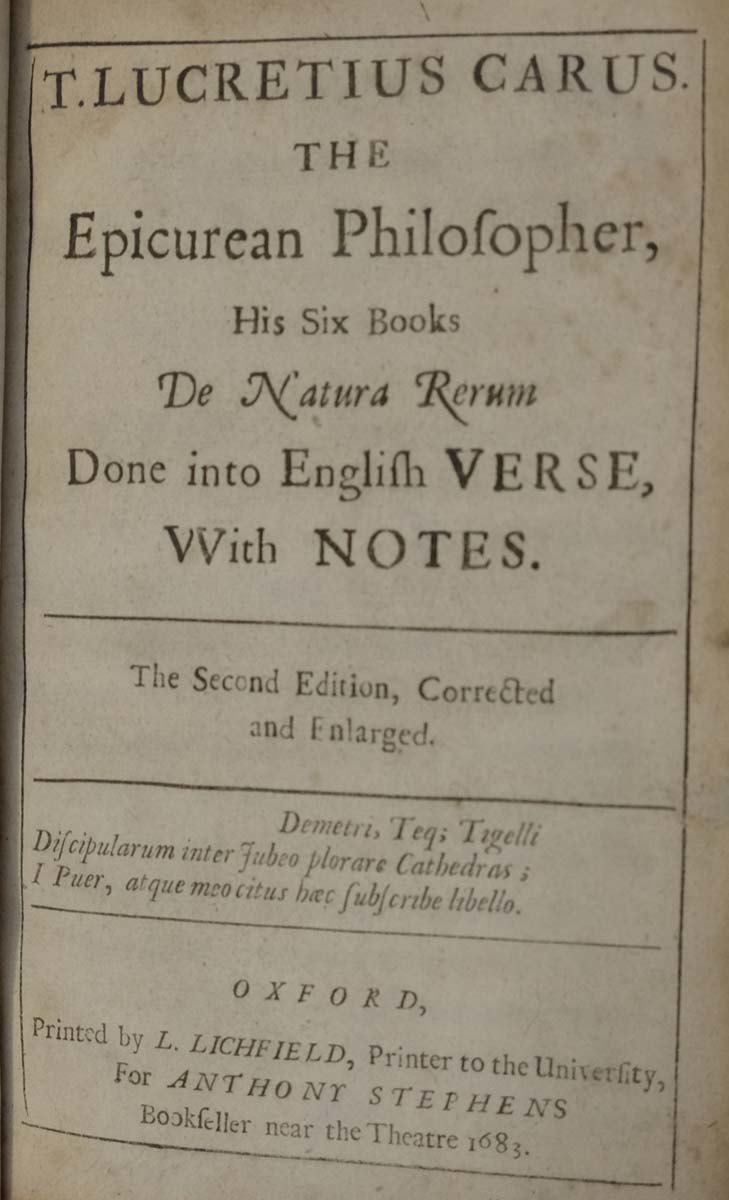

It is one of the most celebrated and instantly recognizable paintings of the Italian Renaissance. Primavera by Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi, or Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), has garnered a mystique surrounding its appearance and its meaning for centuries. The picture’s poetic sources are well documented by scholars and are both ancient and contemporaneous. From the vaunted poets of Roman antiquity (Ovid and Lucretius especially) to Botticelli’s friend and poet Angelo Poliziano, Primavera’s influences are relatively clear to us. In fact, it is Poliziano who is credited with the development of the program for Primavera by many, if not most.

Most have observed in Ovid’s poem Fasti the rudiments of the narrative for the picture, and in particular, the moment on the right side of the composition: Zephyr’s (the god of the west wind) pursuit of the nymph Chloris who is transformed into Flora, the goddess of fertility, harvest, and plenty. Fasti itself celebrates the Roman festival of Floralia, which took place in early spring, with Flora as its titular deity.

Another Roman poet, Lucretius, writes this: “On come spring and Venus and Venus’s winged harbinger marching before with Zephyr and mother Flora a pace behind him, strewing the whole path for them with brilliant colours and filling it with scent.” This quotation seems to be the most direct source for Botticelli. “Venus’s winged harbinger” is Mercury, the herald god, and he occupies the extreme left of Botticelli’s painting. Venus, Zephyr, and Flora too are characters in the picture.

Despite Lucretius being arguably the most relevant poetic source, it seems that Botticelli conflates the Roman’s account with that of his Florentine friend Poliziano, who writes: “lascivious Zephyr flies behind Flora and decks the green grass with flowers.” Lucretius speaks of the relationship of Zephyr and Flora after the metamorphosis of Chloris to Flora. Poliziano’s verse is more darkly turbulent and relates a more equivocal moment. The pursuit by Zephyr implies a time before Chloris’s transformation, while Poliziano’s naming of “Flora” implies a time after it.

Botticelli, however, differs from both Lucretius and Poliziano — we see in the painting the metamorphosis of Chloris into Flora actually occurring. Botticelli’s feat of ingenuity depicts Chloris and Flora with nuance of detail, so this change is shown through time in the medium of painting, which in its stasis would seem to forbid time altogether. Paul Barolsky has written of the transformation of Chloris to Flora as a “gradual process of metamorphosis through time.” He cites the “silhouettes of flowers through the veil of Chloris’s dress,” and the flowers in Chloris’s hand becoming the flowers of Flora’s vestment. In addition, he observes that the “real” flowers are also of course painted by Botticelli, who thus draws attention to the painter’s role in art’s own metamorphosis.

Botticelli’s picture is not a mere summation nor a mere envisioning of his sources. His combinations of figures and thematic moments are distinctly his own. He is not only translating his sources from the medium of poetry to visual art; he is creating a seeming world in which these narratives can breathe. This picture is an exaltation of the possible.

The Context: Patronage and Matrimony

The scholarly consensus dates Primavera to around 1482. It is also believed that the painting was commissioned for the occasion of the wedding of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici and Semiramide Appiano in that year.

Botticelli’s Flora looks out of the composition (the third figure from the right). She, as goddess of fertility and plenty, is an auspicious deity to appear on the occasion of the marriage. Also, she has a symbolic significance on the level of artistic creation. As Botticelli’s muse, she takes on the connotation of the fruitfulness of the visual imagination she inspires. But as well as granting the artist this mode of vision, she also is the embodied evidence of it, as a painted figure. Flora is not so much a feminized representation of the artist as his spiritual cognate. In concert, both Botticelli and the goddess intensify the theme of fertility and procreation that is central to this image.

There is a case for seeing Flora as a visual substitute for Botticelli — strewing flowers from her waist just as the painter offers to his direct patron Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco an unforgettable yet intangible gift, a visual dedication to love and to posterity. However, if we subtract Botticelli himself from the meaning in the image, we can see a narrative progression in the tableau from right to left that directly relates to the betrothed couple.

In this case, Zephyr’s pursuit of Chloris becomes Lorenzo’s of Semiramide or the courtship. Flora is then Semiramide, this time metamorphosed by marriage into the wife whose flowers can refer to her personal charm and the rich gift of her love. The three dancing Graces become guests at the celebration, while Mercury, the herald on the left, becomes the harbinger of summer, harvest, and, by extension, childbirth. All the while, the goddess of love, Venus—the sole note of solidity in the picture—blesses the marriage in the picture’s center. The gesture of Venus’s right hand is a conventional one of invitation. She is welcoming the nuptial pair to the realm of eternal love, the guests to the celebration, and the viewer to the power of Botticelli’s visual imagination.

Oranges are suspended from the grove of trees. In medieval times, the orange was called citrus Medica and was a symbol for the house of the Medici. Botticelli reinforces both the prestige of the leading family of Florence and the theme of the promise of fertility, prosperity, and good fortune for the bride.

Overhead, Cupid, son of Venus, shoots his arrow at the central figure of the three Graces. This lady’s gaze looks out to the left past Mercury to the onset of summer. The Grace to her left looks at her imploringly while raising her hand with her own as if enjoining her to participate in their dance. The central Grace’s expression appears similar to that of Venus, an echo that marks an absorption in love. She is literally lovestruck. Whether this central Grace is a portrait of the bride or not is immaterial. Botticelli provides these several formal and compositional clues that surely tell us that this figure is at least an allegorical reference to the bride.

The Graces themselves were allegorical figures for fertility, charm, joy, beauty, and nature. The three of them were named Aglaea (“shining”), Euphrosyne (“joy”), and Thalia (“blooming”). Here, each of the Grace’s expressions seems to display various modes of a dreamlike state that mirrors that of Venus herself. Their customary joy is shown rather in their dance. In the Tuscan love poetry of the early Renaissance, Venus, Flora, and the Graces were all mythological figures with whom the beloved was compared. In this light, we can see each of these figures as painted by Botticelli as an aspect of Semiramide. Also, we can see them as aspects of love itself: the joy of the Graces, the fecundity of Flora, and the rapture and permanence of the emotion itself in the person of Venus.

There are two diagonals prevailing in Primavera. One comes from Mercury’s raised hand on the left through the raised and interlocking hands of the Graces on one side, and on the other side from the rippling and trailing gales of Zephyr past the upright hand of Flora. These diagonals converge on the lower torso of Venus, approximating the position of the womb. The metamorphosis of Chloris to Flora signals fertility. Together with these signs, the hand signal of Venus—the invitation of summer and the season of harvest—alerts us to the prospective fruit of the womb of the bride.

Also, Mercury as the herald, the messenger, is in harmony with the overall theme of the rebirth of spring, as well as a reference to the future rebirth of the nuptial couple as parents. Semiramide, too, has metamorphosed in the mind of Botticelli to a figure not just embodying the romantic love of her betrothed but, by implication from the visual and thematic clues, representing maternal love. As such, she becomes Venus.

Perhaps instead of one posited portrait of Semiramide, there are three allegorical figures representing her. Although differing in appearance, they each fulfill a different role within the life of the Quattrocento Tuscan bride. The central figure of the Graces displays the nuptial Semiramide, with the figure of Flora revealed as the bride becomes mother. Finally, in a kind of synthesis of these two roles of lover and mother, the central Venus is Semiramide as a totalization of love itself.

Support for this can be found in Botticelli’s formalism — his precise traceable pyramid between the three figures. Flora’s head is honorably wreathed, and the middle of Grace’s head is arched over with the joined hands of the other two. And finally, Venus is crowned.

An Ungraspable Density

Primavera operates in the realm of nuance, from the light to the positions of the figures. The light across the scene is, for the most part, equivocal. From right to left, it is a paler echo of Zephyr’s “silvery blue.” This equivocal light fits with the setting in a forest glade but also it aids Botticelli’s ambiguity. For example, the uncertainty of the ground under the stances of the figures, and the mystery of the interrelations of the figure groups, which seem absorbed in actions local to their part of the composition while sharing the space with each other. However, the dim light is decisively broken in the manner of a literal epiphany (from the Greek to “shine upon”) in Mercury’s sector of the painting. He reaches upward through the foliage with his caduceus to let in the fiery tongues of summer sunlight.

The uncertainty of the ground of the forest glade is emphasized by Botticelli in its slope upwards towards Venus, as well as by the muted colors beneath the flowers. The slope upward is a device to literally heighten the significance of the goddess of love, who is esteemed utmost among the characters from the myth depicted. Her very stance (she is the sole figure with a full foot on the ground) and compositional location on a height point to a constancy that places her outside of time.

We can read the more “foreground” figures as a lateral frieze of characters and actions that are entangled with the changing processes of the natural seasons, but Venus physically stands above and transcends this sometimes-tumultuous and always continuous change.

A further indicator of the location of the frieze in time (time in the sense of the realm of appearances) is the dramatic element. Botticelli’s artifice here can be seen in his deployment of a choric figure, the festaiuolo, or a dramatic character who participates but also directly engages the audience. In this case, the figure is Flora. Within the world of the picture, she strews the flowers of spring. She does this as her gaze outward meets ours, drawing us in. In this, Flora has two modes — that of engagement in the action and a self-consciously dramatic role. These two modes conform neatly to the duality of subject matter and picture, of the eternal process of the seasons and pageantry. Even Botticelli’s drawing is thematic. His characteristically sinuous and fluid lines mark the organic, the continuity of nature, and the passage of time.

His formal choices in composing the painting, from his groupings down to the gestures are full of meaning, and not just visually pleasing. The Zephyr group is in a rapid downward motion from Zephyr to Chloris. However, this sweeping movement is resolved by the upright Flora, whose left arm reaches down in an echo of Chloris’s straining right arm. In the repetition of the arm position, Botticelli highlights the metamorphosis of Chloris to Flora but also of stress to calm. Chloris’s mouth sprouting leaves is a further detail of the transformation.

To the left side, the group including the Graces and Mercury all have their arms raised, except for the left arm of Mercury. These raised arms signal the leavening of the seasonal conditions as summer is presaged to the far left. Venus is upright. Her left arm is lowered on the side of winter while her right is raised in blessing and invitation, with her gaze fixed on the viewer. She, as love, is the constant. She is also the goddess associated with spring. Her lowered left arm, however, could be a gestural affinity with the Zephyr group and late winter. Her raised right hand is situated on a diagonal through the joined raised hands of the Graces to that of Mercury, the god associated with the month of May. The painting is entitled “Spring,” and spring occupies much of the center of the image. But Botticelli here gives gestural indications in his depiction of Venus that love pervades all seasons.

Venus is the only figure in the picture with a heel on the ground. All the others are on their toes or with their feet raised from the ground which itself is of an uncertain position. This is due to the artist’s deft use of subtly varied dark colors, from greens to black. Venus’s heel signifies love’s attributes of resilience and permanence, both in this ethereal forest and in the human realm.

The position of the ground can only be inferred at certain points from the blooming flowers. This ambiguity contributes to the sense of weightlessness of the scene. The figures appear to be suspended in an unearthly idealization of an earthly place. Dancing, the levity of celebration, wind, and metamorphosis all index this weightlessness in the image. Botticelli has painted lightness upon lightness in the figures of the Graces. They stand effortlessly as they dance, while their translucent draperies dance upon their bodies.

The only exception to this is the rapt expression of Venus and the central Grace, the one consumed by love and the other personifying it. Venus’s permanence and solidity are in her upright pose and her right heel, rooted to the forest floor.

Overall, the image is inexhaustible. It represents identifiable deities and narratives. Its poetic sources and immediate context are known almost for certain. It is evidence of the ferment in the crucible of Botticelli’s imagination, as it is both definitively memorable and almost completely evasive of the means of description. Despite the possibility of seeing the image as a dramatic pageant, it is an unspeaking and unspeakable one but, for all that, more alive.