Brazil is widely known for its cultural and religious diversity. Home to a varied range of religions that often mix Indigenous, African, and Christian themes, religious diversity was also prevalent in this region prior to colonization. Often revolving around concepts like animism and a sacred approach toward the natural environment, native religions played a central role in the daily lives of pre-colonial Indigenous communities. Today, many of these practices are being revived in the context of resistance and valorization of Indigenous cultural identities.

Detective Work: How to Study Ancient Indigenous Religions

Indigenous groups in Brazil left no written records; oral tradition was the primary means of passing down tales, practices, and myths through generations. This presents a challenge for historians, anthropologists, and archeologists, who rely on a wide range of methods to recover and study ancient native religions.

A crucial tool in this type of research is ethnohistory. This branch of the historical sciences combines elements from anthropology, history, and ethnography with a critical analysis of sources such as oral histories, colonial records, and archeological evidence. Starting from close work with present-day Indigenous communities, the aim is to reconstruct and interpret religious practices and beliefs within their historical and cultural contexts, understanding how these practices evolved. Ethnohistorians often immerse themselves in communities to observe and record religious practices and social interactions.

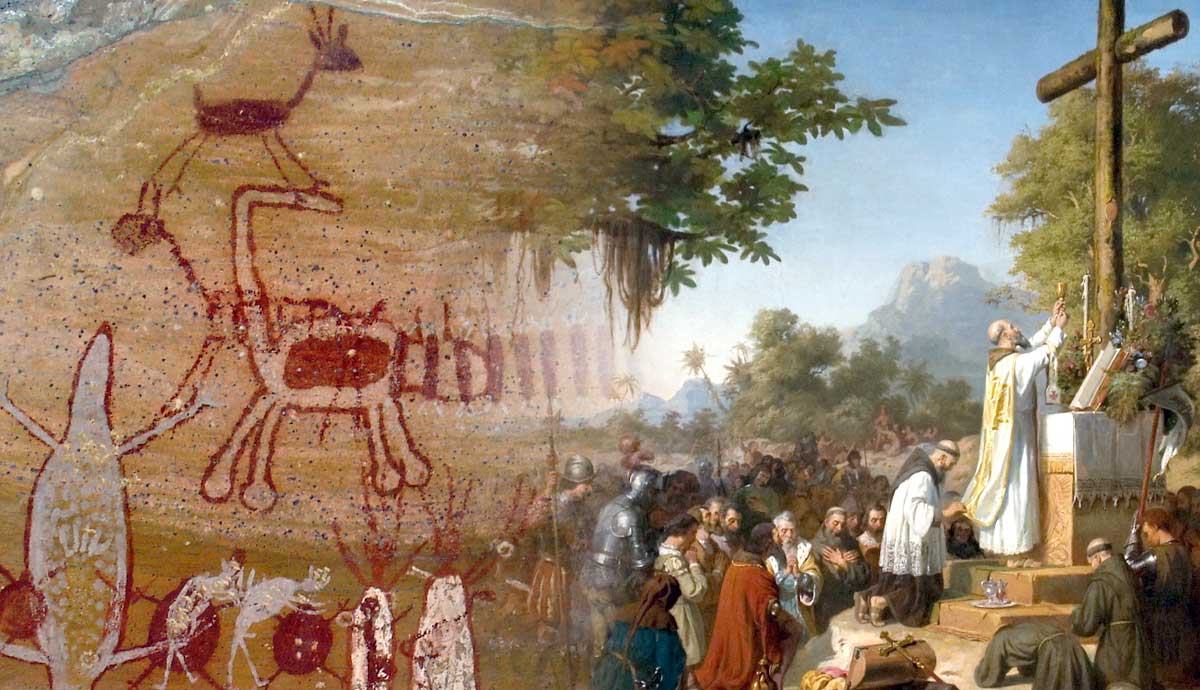

Another resource utilized is written records from European explorers from the colonial period. These texts are valuable historical sources, detailing native peoples’ rituals and beliefs, which seemed exotic to the colonizers. However, a critical analysis is necessary, as the reporters frequently interpreted Indigenous sacred practices through their own cultural and religious lenses.

Archeological records are also relevant to these types of studies. Archeologists often rely on material evidence such as ceremonial objects, idols, and amulets and combine these finds with the examination of sites and burial grounds that display traces of ritual use. This enables a reconstruction of the rites, offerings, and probable sacrifices practiced in the past. Additionally, analysis of iconography and symbols found in pottery, textiles, and cave art may provide insights into ancient mythologies and cosmologies.

One of the earliest and foremost researchers of Indigenous religions and spirituality was German ethnologist and anthropologist Curt Unkel Nimuendajú. Having lived among native communities for several years, his work is essential for the study of native cosmology and sacred practices.

The Worldview of Brazil’s Indigenous Peoples

In the vast and diverse landscapes of pre-colonial Brazil, multiple Indigenous cultures cultivated a profound spiritual connection with the natural world around them. Central to their spirituality, their cosmological worldview often recognized nature as a conscious, living being that communicated and interacted with humans.

Religion and spirituality were central to native identity. For this reason, Indigenous peoples—both past and present—claim that trying to distinguish between the natural, human, and sacred worlds is pointless. In fact, the spiritual practices of Indigenous peoples were integral to their identities and daily lives, with this profound connection to the environment translating into routine activities such as hunting, farming, and social festivities.

Although there are differences in the myths, spiritual beings, sacred practices, and rituals carried out among the diverse range of groups, some key ideas are widespread among the tribes of this vast territory.

Animism: Nature as a Living Being

The natural environment was at the core of most native religious practices. As nature was inseparable from spirituality, its conservation was inherent to their belief systems—harming the environment could be considered a disruption of the spiritual balance. This profound respect for nature led to sustainable living practices that these communities maintained during the many centuries prior to the arrival of European colonizers.

The sacred character of the environment could be found among all the elements of the natural world—animals, plants, rivers, rocks, and the land itself were imbued with spiritual essence and life force. Referred to as animism by anthropologists and historians of religion, this sacred concept holds that all elements of nature are embodied with consciousness and a spirit.

The animistic worldview sees humans as part of a larger web of life, one in which all elements of nature are interconnected. Humans are able to interact with other sentient natural beings, and Indigenous communities often engage in rituals and make offerings to honor and seek the favor of nature’s spirits.

The Role of Shamanism in Brazilian Religion

Contact between European travelers and native peoples has fostered a general fascination with the role of the mysterious religious figures of shamans, who are often shrouded in an aura of mysticism and hold central power in Indigenous communities.

Shamans are the spiritual leaders of animistic societies. They act as intermediaries between the human and sacred worlds, performing rituals, healing the diseased, and seeking guidance from the natural spirits. The original term was coined for the figures found in Siberian hunter-gathering groups, and it is used in anthropology for any religious leader engaged in magical, priestly, sorcery, or healing roles. Supernatural, social, and ecological elements of society are all involved in shamanism.

The term pajé is often used in Brazil to describe individuals engaged in magical activities. The word’s roots are in the Tupian language, and it is usually used in its original context to refer to a specific type of sacred energy or power that is shared by all individuals and particularly manifested in dreams.

The Land Without Evil: An Ancestral Guaraní Quest

The Guaraní were the most widespread Indigenous group in pre-colonial Brazil and the South American lowlands in general. Studies show that the Tupian-speaking populations who broke off to become the Guaraní originated in the territory of present-day Paraguay, on the banks of the Paraguay River. These early groups migrated east, settling on the Brazilian coast, from the southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul up to the state of Espírito Santo.

Religion was at the core of this territorial expansion. Central to the Guaraní cosmological worldview was the idea of the Yvy Mara Ry, translated as “Land Without Evil”. This mythical, otherworldly place is a symbol of the Guaraní’s ideal state of existence in perfect harmony with the natural and sacred worlds. The quest for this utopian land often involved long migrations, ultimately over thousands of miles.

The mythical land could be found sailing eastwards, crossing the ocean. It was reached as a post-death paradise, but could also be found during one’s lifetime by practicing the right rituals. These were designed to purify the participant and seek guidance from the spirits, ensuring the success of the journey. They could involve fasting, ritual bathing, shamanic trances and divination, and the interpretation of dreams.

The “God” Tupã and Christianization

The idea of a central, omniscient, and omnipotent god-like figure was absent from native religions. However, the sacred figure of Tupã commonly stands out when studying the ancient native spiritualism.

The indigenous author Kajá Werá explains in his book The Thunder and the Wind that the name “Tupã” is related to “a state of wonder and admiration that comes from the encounter with the divine,” the word itself probably deriving from an expression that could be translated as “wonderous thing.”

Tupã is related in Tupi-Guaraní mythology and language to the idea of poromonham— an “unmeasurable absolute.” The figure was able to create words by singing, his music serving as guidance for humanity. He is also related to thunder, as the suffix “pá” was a synonym for thunderstorms’ booms.

It was only with the arrival of the Jesuit missions that Tupã would start to evolve from this abstract idea and acquire a god-like figure. The priests would often need to create associations between Christian and native motifs in order to effectively communicate the principles of the colonizing religion.

The mythology of Tupã was widely explored for this purpose. As Christians recognized the importance of this concept for the Tupi-Guaraní, his association with God was emphasized and used to illustrate Christian ideas. This resulted in the modern misunderstanding of Tupã as a god-like figure to the natives when the reality was far more complex and abstract.

The Dead-Worshiping Culture of the Kaingang

In the south and southeastern regions of present-day Brazil, the Kaingang groups engaged in religious activities that are fascinating to study and explore. One of these was Kiki, a ritual designed to ensure the passage of the tribe’s members to the numbê, the world of the dead. Although death was not interpreted as the end of life, the Kaingang believed that the pathway to the otherworld was not automatic—the souls of the dead could only move forward if Kiki was performed. This would allow the disconnection of the dead’s spirits from the living world, enabling passage to the numbê.

Kiki would last approximately ten days and was performed at the beginning of winter, following the harvest of resources such as pine nuts, corn, and honey. It involved three main stages, represented by three big fires in the village’s central square.

The ritual’s name derives from the fermented honey drink ingested during the second day of the sacred performances. On the third day, people from neighboring villages as well as the spirits of the dead would come and participate in the sacred dances performed. However, the spirits were strictly advised against drinking the kiki, as the ingestion of the sacred fermented drink would cause them to become trapped, wandering the world of the living forever.

Scholars believe that Kiki, along with the worship of the dead in general, was the strongest expression of the Kaingang culture. The ritual was studied through ethnographic and oral sources, as well as material evidence such as traditional body ornaments and traces of the sacred drink found on pieces of ceramic containers.

Amazonian Sacred Practices

Reconstructing the religious practices of pre-colonial Amazonians is quite challenging. However, ethnographic research with the modern indigenous groups Achuar and Yanomami has provided some glimpses into what the sacred practices may have looked like in ancient times.

The spirituality of these Amazonian communities was based on the recognition of a “guiding spirit” of plants and trees. These supernatural tutors were responsible for vegetation growth and fertility, especially when related to the wild plants—seen as the crops of spiritual beings. The Yanomami named this spirit Në roperi, while for the Achuar, this being was called Shakaim. For both communities, the forest as a whole is seen as a sentient, sensitive, and intelligent being.

Analyzing the sacred worldviews of these modern-day communities can certainly help visualize how they may have looked in the remote past. The Amazon and its world-renowned biodiversity are the product of centuries of harmonious interaction between humans and nature. Archeological disciplines such as archeobotany and geoarcheology have demonstrated that the natives often altered parts of the vegetation for their own use, changing the location of plants and trees.

This practice would never be pursued without a profound respect for nature, avoiding degradation and destruction of the natural environment. It is reasonable to think that this idea of the forest as a sacred world engaged in agricultural activities would have evolved from these harmonious exchanges.

Legacy and Preservation: Religions as Resistance

Reconstructing indigenous religion is crucial for several reasons. Spiritual practices are often intertwined with the traditions, languages, and worldviews of native communities and central to their cultural identity. For many indigenous peoples, these religions are more than a set of beliefs—they define and enable their relationship with the land, their community, and the cosmos.

Many of the sacred practices of the past are being revitalized by indigenous communities today in an effort to bolster the traditional practices that have been transformed by centuries of colonization. One example is the Kiki ritual; after decades without being performed due to colonization and catechism, it was readopted by the Kaingang community in 1970. This is not just a religious effort, but an act of resistance.

Acknowledging and valuing these indigenous perspectives sends a powerful message to all humanity. Amid the environmental challenges the world is facing, recognizing the critical importance of nature is crucial to all. The health of the planet is intrinsically linked to the respect shown to all living beings—a lesson that native communities have spent centuries trying to teach.