Have you ever instantly disliked (or liked) someone, without being able to say why? Carl Jung would suggest that such powerful reactions may actually reveal a great deal about ourselves. Specifically about parts of our own personality that we don’t recognize. This mechanism is called projection. It’s when we unconsciously ascribe to other people feelings, desires, or even fears that we can’t acknowledge having. For Jung, understanding projection is key to understanding human relationships, political systems, and even (for example) why entire nations might idealize one leader while demonizing another.

What Is Psychological Projection? Jung’s Core Idea

Carl Jung explains that psychological projection occurs when we attribute our own negative traits to others without realizing it. These projections do not arise through conscious effort but rather stem from the unconscious mind. A repository of thoughts, feelings, and desires that we might prefer to keep hidden, even from ourselves.

In Jungian psychology, all individuals possess what he termed a shadow self: aspects of yourself that you reject. If unrecognized, these elements may appear projected onto other people.

Sigmund Freud also discussed projection as a defense mechanism employed to safeguard one’s sense of self (ego). To Jung, however, this was just part of the picture. He believed this process offers insight into how humans engage with the world at large while also providing an opportunity for greater self-awareness.

Consider this scenario: If you continuously label others as selfish, it could be because you are not comfortable with your own selfishness. And when you yearn for more freedom but feel guilty about it, you might say someone is irresponsible.

Jung thought these recurring themes were not only fascinating but also important for personal development. His big idea is that hating something (or someone) may mean we have unfinished business with it—an idea both unsettling and exciting. It can be used to grow up.

The Shadow: What We Refuse to See in Ourselves

The parts of ourselves that we conceal, refuse, or prefer not to confront are what Carl Jung referred to as our “Shadow.” These elements may include laziness, jealousy, vulnerability, or even anger.

Instead of acknowledging them as aspects of our personality, we repress them in our unconscious, where they profoundly influence our thoughts and behavior without our being aware of it. But here’s the irony: when we fail to deal with our shadow side, we project it onto others.

One common form this takes is projection: finding in other people qualities we can’t admit to possessing ourselves.

For example, you may be bugged by someone else’s arrogance when actually you are struggling with your own ego issues (though these will be hidden from view precisely because they are part of your shadow).

Similarly, one way to cope with your temper could be to view anger as a moral failing. This projection allows you to feel smugly superior while not addressing the fact that you, too, get cross regularly.

Jung once observed that every time other people annoy us, it reveals an aspect of our own character to us. This is a profound point: often, our criticisms are like mirrors, reflecting back to us things about ourselves that we would rather not see.

Nietzsche had similar ideas. He warned against fooling oneself and pretending to be something one is not. To deceive oneself can be dangerous.

However, there is nothing wrong with having a shadow side. It makes us human. If we can view this aspect of our character with interest rather than fear, then we may embark on a journey toward greater self-awareness.

The Mirror Effect: Why We’re Drawn to Certain People

Projection doesn’t only manifest in our dislikes. It also appears towards individuals we respect—a phenomenon Jung termed the “golden shadow.” This refers to the moment when we spot beauty, skill, or overall impressiveness in someone and have yet to recognize that it exists within ourselves.

For example, you might be fascinated by a confident individual because deep inside, you wish to assert yourself more. Or perhaps you admire a celebrity’s creativity at a time when your own imaginative flair remains unnoticed.

The concept also works within relationships. Sometimes, the almost magical sensation of “you complete me” reveals qualities that are present in oneself but not fully acknowledged. It is as if those inner attributes are being reflected back like a mirror image.

The same process unfolds with mentors (both personal and professional), teachers, or even best friends. We often feel drawn to them because they represent aspects of who we would like to become.

Plato talked about eros—an intense attraction at the level of the soul that drives us to seek wholeness. He believed love was more than just a feeling for another person. It was about finding a missing piece of our own soul.

The golden shadow in Jungian psychology works similarly. When we admire someone, we often see something we wish we could be as well. Instead of feeling envious or diminished, we can ask ourselves: What does this person have that I also want (or have the potential for)?

Projection in Society

Projection isn’t solely a one-on-one affair—it also operates on a larger scale. When entire groups of people displace their fears or insecurities onto others, the outcome can be prejudice, scapegoating, or even violence.

Consider xenophobia: societies shunning those from outside because they appear different or dangerous. Such societies may be driven by unconscious fears that are not admitted to, such as a terror of change, weakness, or internal disorder.

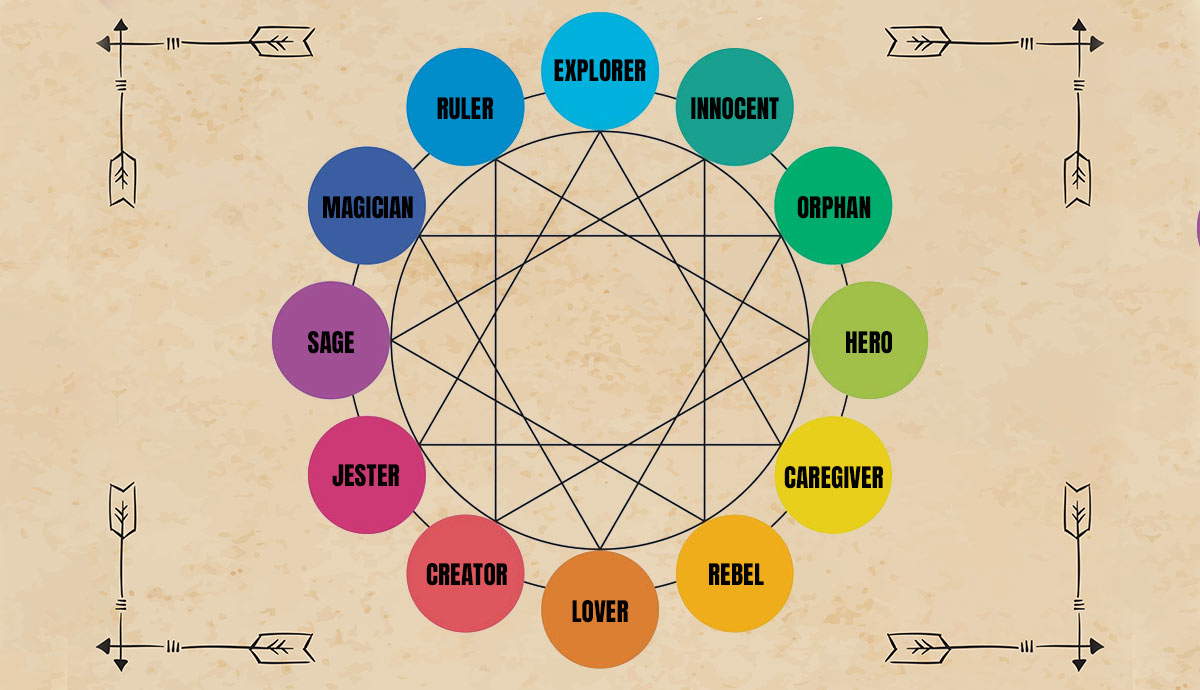

Carl Jung believed in the collective unconscious, a psychological realm shared by all human beings. Here, there are not only archetypal patterns and motifs but also a kind of collective shadow.

If a society refuses to confront its flaws, it tends to project them—often in exaggerated form—onto an external group. Nazi Germany provides a harrowing example of this dynamic. Here, the Jewish people were made to shoulder the blame for problems that stemmed from deep social ruptures.

This type of projection fosters a perilous mindset of “us versus them” that enables individuals to feel virtuous while evading self-reflection. Evil, Jung cautioned, does not only exist in the external world—it also resides within us. And when we deny its existence, it grows stronger.

Philosophers such as Hannah Arendt have referred to the “banality of evil”—the notion that horrific acts can be committed by ordinary people who cease to think critically. Confronting our collective dark side is challenging but essential if we wish to create a fairer society one day built upon truthfulness from top to bottom.

From Projection to Integration

How can we grow instead of projecting? Jung had an idea. It’s called individuation, and it means becoming our true, whole selves. This doesn’t mean being perfect—it means having compassion for all the parts of ourselves, even those we don’t like.

When we notice that we’re projecting (e.g. feeling judgmental about someone else), we have the opportunity to ask ourselves why. Is whatever’s going on with them really what’s bothering us?

Tools such as therapy, dream analysis, and journaling about our Shadow can help us figure this out.

Understanding your projections lets you take responsibility for your feelings. Then, you can do something about them rather than just feeling awful.

For example, many people find it useful to write down their dreams because symbols in the “day residue” often point toward aspects of the self that we reject (or are unaware of), also known as the Shadow.

Embracing our shadows helps us become more complete—not perfect, but authentic. According to Jung, true enlightenment comes from making the darkness conscious, not meditating on images of light. Philosophers such as Nietzsche and Kierkegaard echo this thought. They knew that angst and pain could be the engine of growth.

This isn’t about self-improvement. It’s about being able to meet oneself fully: the good with the bad, the ugly with the beautiful—no longer at war.

Why Projection Still Matters Today: A Path to Empathy

Comprehending projection is not simply a mind game—it is a superpower in life. When you understand that what you react to in others may be more about you than them, something changes.

Instead of reacting angrily, you stop yourself and think: Why does this bother me? Being aware of this can prevent arguments, foster understanding, and keep relationships on track.

These days, emotional intelligence and mindfulness are hot topics in the world of self-help. However, Carl Jung was discussing a similar concept long before such ideas became fashionable. He thought that if people looked at their inner selves (their own dark sides), they might change their views on what was happening outside.

If there is always one person in particular who annoys you, Jung would ask: Why does this provoke me? What exactly about me is being provoked by that person?

This type of cognition results in empathy. Understanding oneself—per the ancient Greeks—is valuable beyond personal edification. It also imparts social insight.

If we can identify our projections, there’s no need for blame. Instead of faulting anyone, we comprehend them. Philosopher Martin Buber argued that to achieve true connection, we must encounter others not as objects (“It”) but as subjects (“Thou”).

Becoming conscious of your dark side, positive attributes, and projections doesn’t just yield personal growth—it can also foster global healing.

According to Jung, the more self-aware an individual becomes, the better placed they are to make out what lies within others. And change, if it’s to occur at all, begins here.

So, What Is Jung’s Projection About?

Jung’s concept of projection suggests that our opinions about others often reveal unconscious feelings about ourselves, both positive and negative. These emotions may give important clues to our unconscious mind.

Instead of just being a way to protect ourselves from difficult truths, Jung believed that projection acts like a mirror. It reveals aspects of our character that we haven’t learned to accept properly.

Becoming aware of these projections and accepting that they may reveal something about ourselves is, according to Jungians, an important step towards personal growth and self-knowledge.

So instead of (or at least before) criticizing someone else, try to see if what you are criticizing isn’t also true of yourself, but in a way, you don’t find it easy to recognize or acknowledge.

If we become more honest with ourselves about who we are and strive to be fairer in our judgments of others, then we are likely to develop greater compassion, both for those around us and for ourselves.