The term “Celtic” is a nebulous one and refers to a broad, heterogeneous group of people spread across time and space. Nevertheless, similarities in religious beliefs and practices are some of the elements that unite the disparate group known as the Celts. This article attempts to provide a high-level overview of Celtic cosmology, explaining where the Celts believed the world came from, what it looked like, and what deities and other powers were active in the world.

What Is Cosmology?

Cosmology is the study of the physical universe. While modern cosmology is an area of inquiry in physics and astronomy, cosmology, as it relates to ancient civilizations, is more of a philosophical study. It is the analysis of how historical people believed the universe to work. Ancient cosmology helped people understand where they came from and navigate their place in a sometimes inexplicable world. Therefore, cosmology includes creation myths, beliefs about the afterlife, and the accepted understanding of the higher powers that govern and shape reality.

The pursuit of identifying a Celtic cosmology is challenging because there are very few sources written from the Celtic perspective pertaining to their beliefs. Nevertheless, archeologists and historians have begun to piece together a plausible picture of Celtic cosmology from excavations of their ritual spaces and accounts of the Celts written by other ancient peoples. This article focuses primarily on Celtic cosmology in Ireland, as it is the most well-represented in medieval texts.

Origins of the Universe in Celtic Cosmology

Though the Celts, especially the Druids, the high-ranking class of religious leaders in Celtic society, certainly had ideas about how the universe came to be, we know very little about this particular aspect of Celtic cosmology. We have a better idea of how they believed humans came to be, particularly with respect to the Celtic peoples living in Ireland.

The Tuatha Dé Danann, or “folk of the goddess Danu,” were a supernatural race of people who settled in Ireland and would become the gods, fairy folk, and high kings, thus rendering the people living in that area their descendants. Therefore, some Celtic cultures believed that humans were the descendants of the deities that they worshiped.

Like other pagan cosmologies, such as Norse cosmology, the Celts probably believed that the universe was divided into multiple realms. The Celts likely believed the sky to be held up above the earth by pillars, with the earth being the middle realm and the sea the lowest realm. The Goidelic word for earth is “talam,” or the proto-Celtic “tela-mon,” meaning “bearer or upholder.” This suggests that the heavens were supported by the earth. The three realms are referenced in early Irish texts, as is the idea of the potential for the heavens to crash down on earth or the earth to fall into the sea.

Apocalyptic Visions

Writings on apocalyptic visions in pagan Celtic Ireland appear in early medieval texts, such Tírechán’s Collectanea, written c. 664 CE. Tírechán’s work asserted that the Druids had their own word for the Christian “day of judgment”, the “day of erdathe,” and that this day would come with fire. Much of this discussion was oriented around Saint Patrick’s arrival in Ireland at Slane during the fifth century CE. Regarding the Celtic fear of fire, Tírechán wrote of Saint Patrick:

“He came to the spring of Findmag which is called Slan, because he was told that the druids honored that spring and sacrificed gifts to it as if it were a god. It was a four-sided spring, and there was a four-sided stone in the spring’s mouth; and the water came over the stone, that is, through the mortar, like a royal road. And the unbelievers said that a certain deceased prophet made a casket (bibliothica) for himself in the water beneath the stone, so that his bones could whiten for-ever, for he feared the burning of fire (ignis exustionem).”

Saint Patrick’s role in early medieval Irish fears about the end of the world, rooted in their pagan past, is somewhat unclear. It is said that he made a request of the Christian God that the Irish be destroyed by the sea seven years before the day of judgment, rather than be subject to it. This could have been influenced by his purported observation of the pagan prophet requesting to be buried underwater out of fear of fire.

It is also said, however, that Saint Patrick announced his arrival in Ireland at the Boyne Valley on the Hill of Slane by lighting the Paschal fire in celebration of Easter and in defiance of the nearby pagan festivities on the Hill of Tara, where Druids were celebrating the Feast of Tara. When the Druids observed this fire, they reported to King Laoghaire that if it were not extinguished that night, it would burn forever. The king and the Druids challenged Saint Patrick, lost, and eventually accepted Christian conversion. Perhaps this was the “apocalypse by fire” that was foretold by the pagan Celts.

A Celtic Pantheon of Gods

A pantheon refers to the officially recognized gods of a given religion. Putting together a definitive Celtic pantheon is nearly impossible, as the various Celtic cultures living across Iron Age Europe worshiped a variety of deities particular to their geographic area. There are, however, a few gods that were consistently worshiped by multiple groups of Celtic peoples.

These gods include Danu, the Celtic mother goddess and goddess of earth and fertility; the Dagda, the father god and god of agriculture and the seasons; Morrigan, the goddess of war, death, and fate; Brigid, goddess of healing, wisdom, and smithing, as well as the goddess celebrated during the pagan holiday Imbolc; Lugh or Lugus, the sun god; and Cernunnos, god of the forest and animals.

It is thought that the Celts believed that the gods were responsible both for human existence, whether through creation myths or as divine ancestors, and for their lived experience. They believed that worshiping the gods would ensure prosperity and success for their community.

The Celts also believed in animism, or the belief that all things in the natural world possessed a spirit or a soul. This includes trees, rivers, rocks, animals, lakes, and even wells. They believed that these aspects of the natural world were possessed by the indwelling spirits of gods, godlings, and other minor deities, and that they all required worship through the form of prayer and ritual offerings. This is supported by the archeological record and suggests that the Celts felt a spiritual connection with their landscape.

The Tuatha Dé Danann and Irish Mythology

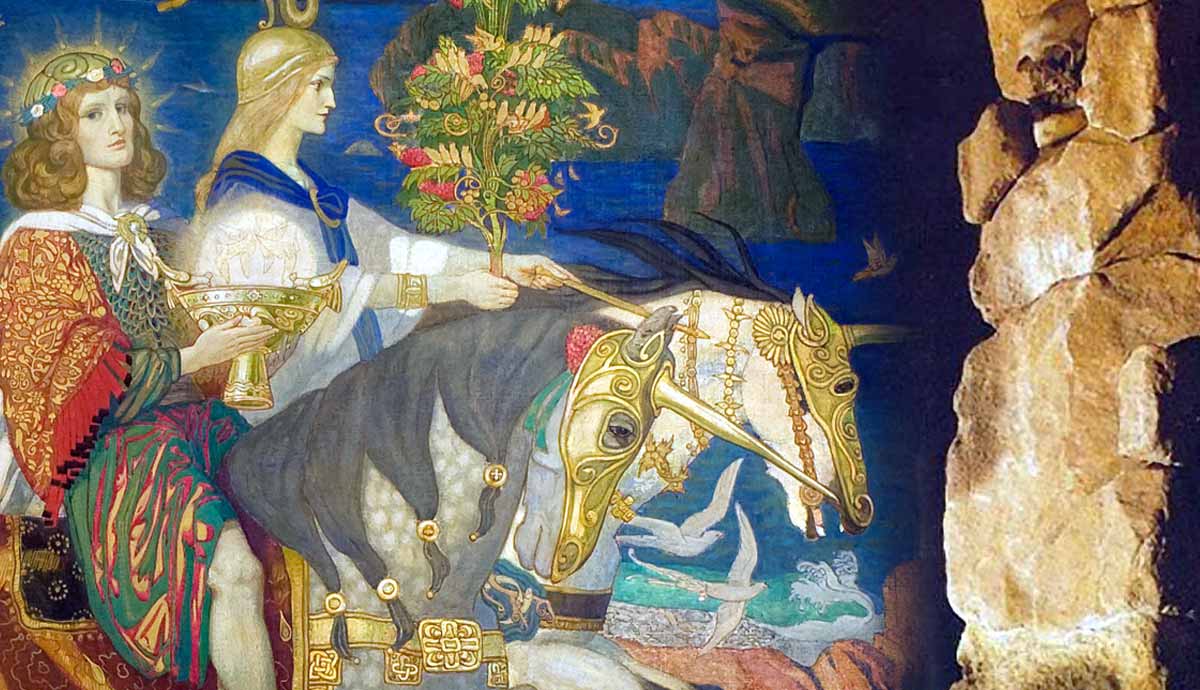

As discussed above, Irish mythology traces its pagan roots back to the legendary Tuatha Dé Danann. These were a supernatural race of beings, often depicted as kings, queens, druids, bards, warriors, heroes, healers, and craftsmen, and thought to be the deities of pre-Christian Ireland.

Many of the texts on the Tuatha Dé Danann were written by medieval Christian authors interested in Irish mythology, but trying to understand it through the lens of Christianity. Some legends hold that the Tuatha Dé Danann eventually became the high kings of Ireland, meaning that the Irish people were their descendants. Others believe that they left this world to go into the Otherworld, with the arrival of the Gaels in Ireland. Many of the gods and goddesses of the Celtic pantheon are said to have been members of the Tuatha Dé Danann, including the Dagda, Morrigan, and Lugh.

The Tuatha Dé Danann are often associated with specific places in the landscape, particularly the sídh mounds. These are ancient burial mounds and passage tombs in Ireland that are believed to be entrances to the Otherworld. One such place often associated with the Tuatha Dé Danann is Newgrange, a neolithic monument, passage tomb, and space for ritual worship that was built by c. 3200 BCE. The mound was initially thought to be the resting place of the Dagda, but some legends suggest that he was tricked out of ownership of Newgrange by his son, Oengus Óg. Regardless, the Tuatha Dé Danann and the various tales of their lives are thoroughly baked into Irish mythology and are heavily associated with pagan and Christian Irish thought on the origins of the universe.

Druidic Practice: Realms, Cauldrons, and Elements

While the Druids are one of the most popular aspects of the Celtic past, we know very little about them and their practice. What we know about Druidic belief comes from Roman encounters with them and medieval texts attempting to elucidate what their ritual work looked like. Julius Caesar wrote of the Druids in his Gallic Wars, saying that they prohibited their members from writing down their religious beliefs, as they did not want their doctrines to become public knowledge. They preferred their practitioners to memorize their teachings rather than being able to consult texts. Historians maintain that Druids were likely among the highest-ranking members of Celtic society and were certainly its religious leaders.

As Druidic belief was not recorded, it is difficult to come to a complete picture of it, and modern Druidry has little connection with ancient practices. Nevertheless, Luke Eastwood, a modern Druid and writer, has written that they likely believed in the importance of the four compass directions as well as above, below, outside, inside, and through. These nine directions corresponded with the nine elements (Dúile) related to the cosmos (Bith): stone, earth, plant life, sea, wind, moon, sun, cloud, and heaven.

These elements were intertwined with the three realms of the cosmos, sky, land, and sea, as well as the three cauldrons of the human body: wisdom (sois), related to the head, vocation (ernmae), related to the body, and warming (goriath) related to the blood. The three realms are represented in the Bile Buadha or World Tree. The universe unites all these things together through a life-force that flows through all things. This idea is related to the previously discussed notions of animism, that all things possess a life-force in Celtic thought.

Interestingly, Norse mythology is also focused on a mighty world tree called Yggdrasil, and considered the number nine sacred, with the cosmos being composed of nine realms.

That this is a rough outline of the Druidic belief system is supported by the kinds of rituals that archeologists believe them to have practiced. They are believed to have conducted rituals in sacred tree groves, specifically oak groves, which could provide a connection to the World Tree and a source of innate strength. Trees were very significant in Celtic belief, not just because of the World Tree, but also because of the idea that the sky was held up above the earth by pillars. Trees could have been believed to be the very things protecting the earth from the sky falling onto it.

Death, the Soul, and the Afterlife (Otherworld)

Julius Caesar wrote that the Celts believed that “souls do not become extinct, but pass after death from one body to another, and they think that men by this tenet are in a great degree excited to valor, the fear of death being disregarded.” Celtic ideas about the soul were further explored by Diodorus Siculus, who wrote that they believed “the souls of men are immortal and that after a prescribed number of years they commence upon a new life, the soul entering into another body.” It has been theorized that this “other body” that the soul occupies after death is a divine body existing in the Celtic Otherworld, or afterlife, which is believed to be inhabited by the Celtic gods.

This idea of the soul existing in a divinely charged space after death lent itself to the development of the Celtic cult of the head and the practice of headhunting, head collecting, and displaying human heads, particularly in a ritual context. Celtic nobles also purportedly displayed human heads as proof of their conquests and military prowess. Sacred sites like those located at Roquepertuse and Entremont in France, formerly Gaul, support the notion of Celtic ritual worship of the human head. The Celts held that the head was the seat of the soul, and therefore the disembodied head, channeling its Otherworldly body, could allow the living to intercede with the divine.

How the Otherworld was accessed by the deceased varied between Iron Age Celtic cultures. Burial mounds could have been considered gateways between the mortal world and the Otherworld, particularly as burial mounds were often furnished with supplies for the deceased to take with them. Other Celtic groups are thought to have potentially engaged in ritual water burial for their dead, believing water to be a liminal space where the boundaries between the living world and the Otherworld were blurred.