One of the main causes of the end of the Viking era was the Vikings’ conversion to Christianity. This changed their political relationship with their neighbors, making raids more difficult, and made them less distinct from the rest of Europe. While there are stories of Christian missionaries and Viking conversions as early as the 8th century, widespread conversion started in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. But what was the process and timeline for conversion, and what was the attraction of adopting a new religion?

Conversion of Denmark: Harald Bluetooth

The key figure in the Christianization of Denmark was King Harald Bluetooth. He was the son of King Gorm the Old, a Norse pagan, and Queen Thyra, a Christian.

Harald is said to have been baptized while his father was still alive, in around 930 CE, to make alliances with his German neighbors. At the time, Christians were only supposed to enter into agreements with other Christians, so pagans would undergo baptism to make agreements legitimate.

He is then said to have converted in earnest shortly after succeeding his father in 958 CE, when a missionary named Poppo proved the power of God by performing a miracle: holding a hot iron in his hands without injuring himself. This event is depicted on a gold decoration from the front of a church altar from Tamdrup in Jelling, possibly dating to around 1200 CE. The images also show the baptism of Harald Bluetooth.

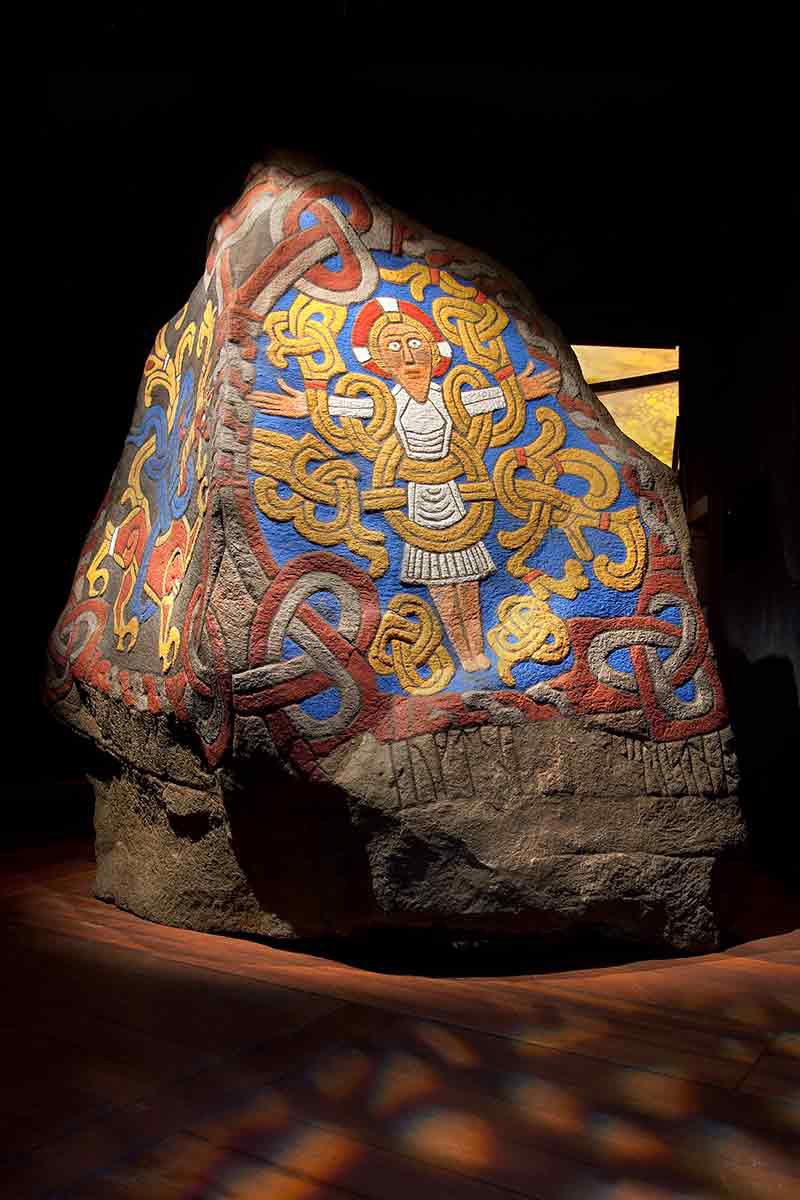

Witnessing this miracle prompted Harald not only to convert but also to establish a new Christian capital for himself at Roskilde on the island of Zealand. Nevertheless, he also erected the famous Jelling stones to both honor his parents and the conversion of Denmark, newly established as a unified kingdom, to Christianity. One of the stones displays an image of a crucified Christ, which has been likened to images of the Norse god Odin hung from Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life.

According to the German chronicler Adam of Bremen, Harald’s son, Sweyn Forkbeard, rebelled against his father and Christianity and set himself up as an opposing pagan ruler in Jelling. He eventually drove his father out of Denmark, along with the German bishops. Adam of Bremen describes Forkbeard as doing this because he was a staunch pagan, intolerant of Christianity. He also claims that Forkbeard was exiled to Scotland for 14 years and only found success as a king when he returned as a Christian.

This story is not consistent with what we know of Sweyn Forkbeard. We don’t know how he succeeded his father, but there is no evidence that he underwent an extended period of exile. He did go on to make himself the king of England, and when he died there, his body was sent back to Denmark to be buried in a church he had built. However, we also know that he recruited priests and bishops from England to travel to Denmark, preferring them to German bishops from Bremen, perhaps explaining Adam of Bremen’s antagonism towards him.

Christianization continued in Denmark over the next century. King Canute IV, who ruled from 1080 to 1086, was expelled from office, firstly because he was passing laws in his own authority rather than using the traditional Thing assembly, which was intimately linked with pagan religion. Secondly, wealthy nobles were unhappy with the tithes they had to pay for new churches and monasteries. So, while the issues were linked with Christianity, the real issues were autocracy and taxes. A century later, in 1188, Canute was canonized, by which time Denmark was thoroughly Christianized.

Conversion of Sweden: The Battle for Uppsala

There is evidence for early attempts at Christianization in Sweden. For example, the German bishop Ansgar constructed churches at Birka and Hedeby in the first half of the 9th century but attracted few to his cause. A century later, there were further attempts by a German bishop called Unni and English missionaries, but they didn’t have the support of the Swedish leadership.

It was only at the end of the 10th century, in the 990s, that the first Christian king of Sweden, Olof Skotkonung, ascended to power. But unlike Harald Bluetooth, he was not powerful enough to convert his nation. Instead, an agreement of religious tolerance was struck between the king and pagan leaders at the important pagan cult center at Uppsala. Nevertheless, this would open the door for the establishment of more churches and Christian centers, and Christianity began to trickle in.

According to the Orkneyinga saga and the Hervarar saga, in the 1080s, King Inge the Elder tried to end pagan sacrifices at Uppsala. This caused public outcry, and he was forced into exile. His brother-in-law, Blot-Sweyn, was made king in his place, on the condition that he allow sacrifices to continue. After three years, Inge returned and killed his brother-in-law, retaking power and, according to the Hervarar saga, forcing widespread conversion of the Swedes. However, the Heimskringla suggests that Inge had challenges to his power from other pagan nobles and leaders.

Nevertheless, progress continued, and between 1134 and 1140, a Christian center, an episcopal see, was established at Uppsala. When the Pope established its archdiocese in Sweden in 1164, it was also at Uppsala.

Olaf Tryggvason: The Christianization of Norway, Iceland, and Greenland

The conversion of Norway to Christianity started with King Hakon the Good in the 10th century. The son of King Harald Fairhair, the king sent this younger son to the court of King Aethelstan of England, probably as a hostage. There, he was taught to be a Christian. With King Aethelstan’s support, he took power in Norway from his half-brother Eric Bloodaxe and became the first Christian king of Norway in 934. However, the Historiae Norwegiae says that he allowed both paganism and Christianity to flourish during his rule.

His death in 961 CE was followed by decades of inconsistency, with his successor Harald Greyhide destroying pagan temples, and his successor Hakon Jarl leading a pagan revival, despite pressure to convert from the neighboring Danish king Harald Bluetooth. But it was with the rise of Olaf Tryggvason that Norway truly converted.

Olaf Tryggvason was a grandson of Harald Fairhair, who ousted Hakon Jarl and made himself king of Norway in 995 CE. While he was raised pagan and then spent the early years of his life raiding and as a mercenary, he reportedly converted to Christianity after receiving an accurate prophecy from a Christian See on the Isles of Scilly. He also relied on an important alliance with the Holy Roman Emperor Otto II to maintain his power, so Tryggvason zealously sought the conversion of Norway.

King Olaf sent missionaries to other lands, successfully converting the Orkney Islands, which were part of Norway. At home, he is said to have destroyed pagan temples and forced people to convert using threats of exile, hostages, mutilation, and torture. These actions made Tryggvason unpopular, and he died at the Battle of Svolder in 1000. Nevertheless, the process of Christianization continued under his successor, Sweyn Forkbeard, whom we have already met. When Pope Adrian IV visited Norway in the 1150s, he established the Norwegian archdiocese and canonized Olaf Tryggvason as a Christian saint.

Olaf’s zealousness also saw the conversion of Iceland and Greenland. According to the sagas, many of the original Icelandic settlers in the late 9th century were already Christians. This suggests that the pursuit of religious freedom may have been one of the motivations for migration. A century later, Olaf sent missionaries to Iceland to force conversion. The Icelandic leaders decided that Iceland needed to unite if it wanted to remain independent of Norwegian power, and this required religious unity. They decided that everyone should be baptized as a Christian, though private pagan practices would be tolerated. Over time, Christianity became dominant, and laws were passed to outlaw certain pagan activities.

The conversion of Greenland was less dramatic, beginning with Tryggvason baptizing Leif Erikson, the son of the colony’s leader, Erik the Red, when he spent time in Norway. Erikson’s mother was already a Christian, but his father was a staunch pagan. It was relatively straightforward for Erikson to lead the conversion of the small community when he took over as leader following the death of his father.

Why Did the Vikings Convert to Christianity?

While this explains the history of the Vikings converting to Christianity, it does not fully explain why the Vikings chose to abandon their sophisticated native religion for Christianity.

On many levels, it was political. As we have seen, the first baptisms were probably done purely for show to secure trading agreements and treaties. But then we see rulers like Hakon the Good and Olaf Tryggvason taking power with the support of powerful Christian kings such as Aethelstan of England and the Holy Roman Emperor Otto II. Encouraging widespread conversion was often a condition of these alliances.

In addition, Viking society was changing. In the early Viking Age, Vikings were divided into small communities of independent landowners who gave their loyalty to a local chief. But in the 10th and 11th centuries, those smaller entities were being consolidated into larger kingdoms under powerful kings like Harald Bluetooth. This mandated a change in approach.

With bigger communities and more diverse interests, it was harder to rule via the Viking Thing, which required gathering powerful nobles and ruling by common consent. We saw King Canute IV fall foul of the Thing. More attractive was the autocratic rule of Christian kings, supported by the vast administrative infrastructure of the Church, needed to administer growing territories.

It is noteworthy that the Vikings left behind very few written texts in their native runic language, and certainly nothing that looks like a ledger or law code. These only emerged with the rise of Christianity and the adoption of Latin text, even when it was adapted to express the Norse language. We hear of Christian priests and bishops in Scandinavia, where they would have assisted the administration. This made their presence political, as we see with Sweyn Forkbeard expelling German bishops in favor of priests from England.

Viking leaders also knew that the Church represented a potential source of wealth; they had raided enough of them over the years. Raiding became more difficult with conversion as Christians were discouraged from attacking other Christians, and certainly from attacking the Church. But raiding had already become harder as their typical targets became better at defense, fortifying their communities, and moving important religious sites inland beyond Viking reach. For many leaders, it was time to start using the Church to accumulate wealth in other ways, like we see with Canute’s tithes.

When it came to converting nobles, being baptized represented a way of demonstrating acceptance of the new political structure and allegiance to the king. Nobles would have had their own dependents convert in turn, leading to a top-down conversion process.

The king may have cared little about the religious beliefs and practices of individuals, and many who “converted” probably continued pagan practices. Interestingly, we find traditional Thor’s Hammer amulets decorated with crosses, indicating people with a foot in both camps. However, the Church put pressure on leaders to encourage true conversion, leading to the destruction of pagan temples and laws outlawing certain pagan practices.

Greater intermixing with Christians from other parts of Europe would also have been a factor. We know that Vikings who settled in new territories, such as England and France, converted quite rapidly. They took local Christian wives and participated in the local community that often centered on the Church. The Vikings also brought Christian slaves back to Scandinavia with them, where they lived side-by-side. We hear of many examples of pagans and Christians marrying in the Viking world, such as the pagan Erik the Red and his wife Thjodhild.

All of these factors played a part, and conversion was a gradual process that took around 200 years. But conversion does not mean that traditional religion was completely forgotten. The 10th-century Gosforth Cross from a Viking community in England is a Christian monument, but shows imagery from Norse mythology, including Ragnarök.