The tragedy of Armero was one of the most horrific natural disasters witnessed in Colombia’s history. Occurring almost 40 years ago, the tragedy was caused by the eruption of the Nevado del Ruiz Volcano in the central Andes Cordillera. The deadly eruption happened on November 13, 1985, and triggered the melting of lahars that buried an entire nearby village, Armero, killing most of its residents. Although the volcano had been silent for over 70 years, it had shown signs of possible eruption for several months before the tragedy.

Where Is Armero?

Armero was the third-largest urban center in Tolima, Colombia. It was 48 km (30 m) away from the Nevado del Ruiz volcano and was an important agricultural center known for its rice production.

Volcanic activity in the region was not uncommon. It has been registered since the 16th century, with activity peaks during the 19th century. After the explosion of Mount Pelée in 1902 on the French island of Martinique, Nevado del Ruiz’s eruption is considered the second-largest volcanic event of the 20th century.

Nevado del Ruiz Volcano

This snowy volcano is located in the northern part of the Andes volcanic belt between Tolima and Caldas in Colombia. More specifically, it is part of a national park, the Parque Nacional de los Nevados (Snowy Mountains National Park), which lies on the Pacific Ring of Fire.

The volcano has remained active since the Pleistocene. Typical eruptions include the expulsion of pyroclastic flows that can melt surrounding glacier ice and produce lahars, or volcanic mudflows. The volcano’s ice cover is an important potable water resource for nearby villages. However, due to climate change, it has been decreasing in recent years.

Volcanic activity and eruption events have been documented at Nevado del Ruiz since the 16th century, and especially during the 19th century. Because the last major eruption had happened 140 years before the day of this tragic event, for the locals, it was easy to ignore the potential threat. Moreover, smoke from the volcano had rarely been seen as a cause for alarm by nearby populations. Following the 1985 explosion, the most recent eruption happened in 2012, with the volcano expelling only gases and ash.

Although people had been aware of Nevado del Ruiz’s volcanic activity since early November 1984, geologists had identified increasing seismic activity in the region and a more visible expulsion of smoke from the different volcanic chimneys. Direct contact between magma and water produced an explosion on September 11 of the same year, leading local authorities to prepare evacuation plans and produce risk maps published in different national newspapers. Unfortunately, this information did not reach Armero’s population effectively.

One Year Later: The Night of November 13

At 3 p.m. on November 13, 1985, columns of ash were expelled from the volcano. By 7 p.m., ash rain had started to fall over the village. The director of the Colombian civil defense was informed about the peculiar events and issued recommendations to evacuate nearby villages. Some survivors have shared that the village mayor, informed of the imminent risk of eruption, walked the streets warning the people. Despite his efforts to save Armeros’ people, other authorities recommended that the people remain calm and return to their houses. At the same time, the Colombian Red Cross started organizing evacuation plans in nearby villages. At 9:09 p.m., the volcano erupted, throwing pyroclasts 30 km (19 mi) into the atmosphere. After the explosion, the Colombian National Geological Service recommended immediate evacuation. However, due to storms, these warnings never reached Armero’s authorities.

The volcano’s explosion melted 2% of the mountain’s glaciers, producing lahars that traveled down the mountain through descending river courses, reaching speeds up to 60 km (37 mi) per hour. Lahars mix mud, debris, and water. Before hitting the village, the main lahar traveled through the Lagunillas River, which neighbored Armero.

Around 11:30 p.m., the first lahar reached the village, followed by the arrival of 350 million cubic meters of mud mixed with branches and rocks that reached 30 meters (98 ft) in depth. Almost instantaneously, nearly the entire village was submerged, destroyed below the mudflow. The mud crushed buildings and people and smothered many.

Absent warnings from the government, and due to the timing, with many already sleeping, 20,000 people died, corresponding to around 94% of Armero’s population. After the mud had covered the village and destroyed connecting bridges and roads, it was almost impossible for the emergency services to reach the people. Twelve hours after the event, the first emergency services could finally reach the survivors.

The Next Day: Desolation

The next day, emergency trucks came to begin removing bodies that were buried and stuck between rubble, rocks, and trees. Some of them were cremated. The total toll of affected people reached 230,000, and initial damages were calculated to be approximately USD $218 million. Because the lahars had destroyed the local hospital, wounded people were moved to hospitals in nearby urban areas, most of them forever displaced by the tragedy and separated from their families.

Playing Politics: Delayed Response

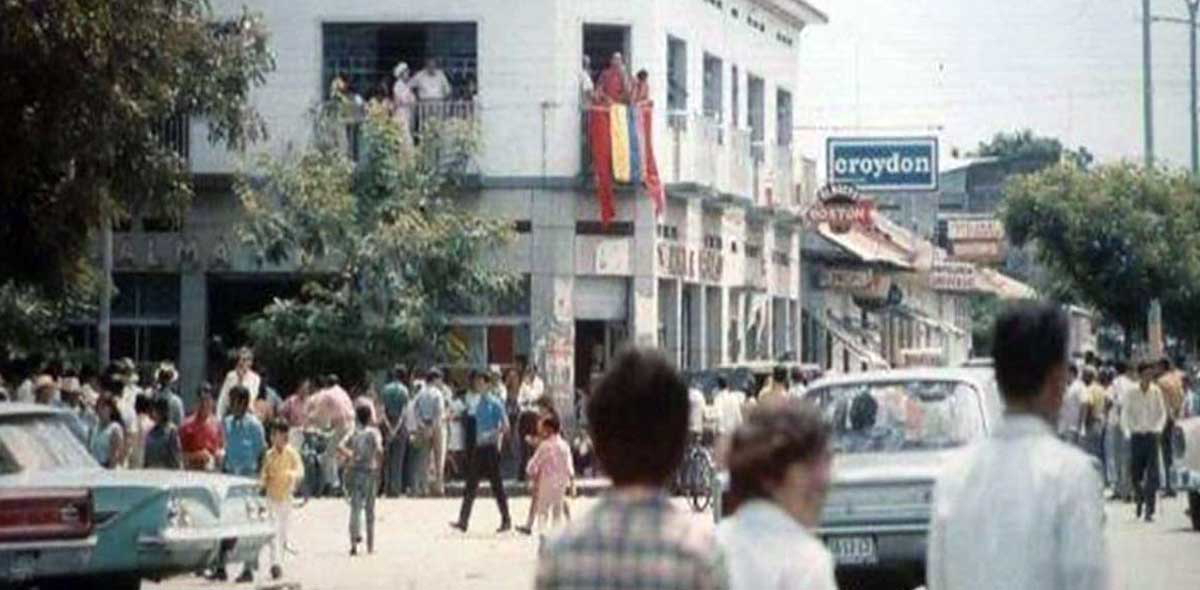

After the flooding, recovery operations for the victims were both slow and poor. Colombia’s political landscape was unstable, and the government was directing its attention to other issues. One week before the event, the Colombian Palace of Justice had been occupied by the M19 guerilla movement, which was garnering most of the country’s attention. At the international level, the eruption of Nevado Del Ruiz happened only two months after an 8.1 magnitude earthquake struck Mexico City, which limited the number of supplies sent by the international parties.

Despite the unstable landscape, less than a year after the catastrophe, on July 7, 1986, Pope John Paul II visited the site as part of his six-day tour in Colombia. There, the pope declared the terrain a holy ground. A high cross penetrated the now-dried mud, where the pope knelt and prayed.

Omayra Sánchez, Face of a Tragedy

Omayra Sánchez was a 13-year-old girl who was trapped in the mud for 60 hours before she passed away. She became the symbol of the Armero tragedy because of her story of resilience and hope amid her unavoidable fate. After the flooding, her legs had been trapped in the rubble. A rescue team of divers tried to free her from the debris trapping her, only to realize that the arms of her aunt were holding her tightly from the depths of the water. Efforts to rescue her were broadcast on national television, and a picture of her taken by journalist Frank Fournier was named the photo of the year by World Press Photo of the Year in 1986.

In the subsequent years, Omayra became a source of inspiration for literature and music, in the works of writers such as German Santa María Barragán and Isabel Allende. Her figure also attracted worshipers, who have been trying to secure her beatification. Today, the site of her passing has become a place of pilgrimage and offerings for many who still commemorate and believe in her.

Armero Today

Driving between the cities of Ibagué and Honda, travelers pass by what is left of the village: to the right, abandoned houses half-buried, and to the left, half of a hospital still popping out from the ground. The site is visited by many people who come either as tourists or pilgrims to the sacred site for the curiosity of worship.

Every year, on November 13th, more visitors gather, and different commemorative activities occur. Some are survivors. Others are descendants of the victims. As an act of remembrance, the Colombian Army throws rose petals from helicopters while masses are celebrated on the holy ground. Five kilometers away, a new village called Armero-Guayabal was built to house thousands of survivors. After the tragedy, many orphaned children were lost; some were even kidnapped. However, despite some being rescued, tracking adoptions is basically impossible because of the lack of a functional registry system.

Francisco González, one of the survivors, lost his father and brother on the day of the event and founded an organization called Armando Armero (Building Armero). This institution is currently fighting alongside other survivors to find the lost children who, in some cases, were adopted by foreign families. They have filed a complaint against the Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (Colombian Institute for Family Well-Being), which, in 2021, declared that it did not have official records about the protocols used for rescuing and protecting the young survivors.

Lessons Learned

The incredible number of deaths in Armero was caused, in significant part, by misinformation and the inability of mass media to deliver an effective warning message. Geological services could not communicate in a timely fashion with local emergency services in Armero, while local people ignored the signs of imminent danger, beginning with the ash rain that fell that afternoon.

In 1985, Colombia did not have the proper live geological measurement equipment. However, after the Armero tragedy, different geological monitoring services and technologies in Colombia were improved and developed, and today cover 25 active volcanic zones out of 50 present in the nation’s territory. In 1988, Colombia created the Sistema Nacional para la Prevención y Atención a Desastres—SNPAD (National System for Disaster Prevention and Response), and in 2012, the Sistema Nacional de Gestión de Riesgo de Desastres—SNGRD (National Disaster Risk Management System). These, together with the Servicio Geológico Colombiano—SGC (National Geological Service), are today the institutions that work together to safeguard vulnerable communities in high-risk disaster zones. Armero also testified to the importance of an effective preventive organization that takes into consideration Colombia’s complex geological characteristics, which must entail collaboration between government and scientific institutions.

The Amero tragedy is a reminder of the devastation volcanic eruptions can have on nearby urban and rural areas and how preparedness is a vital tool to mitigate such risks. In the case of Armero, miscommunication and misinformation exacerbated the loss of lives, which had a long-lasting social impact on the country, especially for the survivors. Lastly, the search for the young survivors of the tragedy reflects how important it is to have effective rescue and protection protocols in place in the aftermath of disasters.