The dual claims that Jesus was crucified and later appeared alive to his disciples have failed to persuade many. Of the two, the miraculous nature of the second meets the most resistance today. But for some in the past, both claims have proven problematic, and alternative explanations have been proposed. One recurring type of explanation may be categorized as “replacement theories”—retellings that feature a substitute for Jesus either at his crucifixion, his subsequent appearances to his disciples, or both. History has preserved at least five such theories.

1. The Twin Theory

The Gospel of John in the New Testament refers to Thomas, one of Jesus’s disciples, as “Didymus,” the Greek word for “twin.” It is not uncommon for New Testament characters to go by more than one name. But the name Didymus appears to suggest that Thomas had a twin. Yet, the Bible never says whose twin he was.

A later work called The Acts of Thomas purports to tell the story of Thomas’s ministry after the events of the New Testament. In one scene, Jesus appears to a bride and groom, who are acquaintances of Thomas, on their wedding night. The couple mistakes Jesus for Thomas because the two look exactly alike. The text stops short of claiming Jesus and Thomas are twins, but in appearance, they are portrayed as identical.

While the idea that Jesus had a look-alike brother is not used in ancient sources to explain his alleged postmortem appearances, it nevertheless laid the groundwork for the theory to arise later on. The theory proposes that, perhaps such a brother was crucified instead of Jesus—and then Jesus subsequently appeared either claiming to have been raised from the dead or, being seen only from a distance, facilitating the legend that he had done so. Alternatively, perhaps Jesus was indeed crucified, but then his identical brother—who for some reason had been in hiding—appears on the scene claiming to be Jesus.

The existence of Thomas himself in the Gospels poses a problem for this replacement theory. But Thomas’s tantalizing title in the Gospel of John—“The Twin”—along with the ancient tradition about Thomas and Jesus’s uncanny resemblance are nevertheless to be credited with inspiring it.

2. “Another” Was Crucified While Jesus Laughed

A 1945 discovery at Nag Hammadi in Upper Egypt opened a window into an early strain of heterodox Christian philosophy called “Gnosticism.” Christian Gnostic interpretations of the death and resurrection of Jesus tend to reach for alternative explanations based on secret or hidden knowledge to which only a few, chosen persons are privy.

An example of this approach is The Second Treatise of the Great Seth. One of the volumes in the Nag Hammadi collection, this work presents itself as a collection of Jesus’s sayings. Jesus explains in this discourse that he was actually not tortured and killed at all. Rather, it only appeared that he suffered, while another was crucified in his place. The text mentions that a man named Simon bore Jesus’s cross, and then mentions “another” on whose head the crown of thorns was placed. Jesus, however, stood on a high place overlooking the scene and laughing at the ignorance of those who thought they were killing him.

Gnosticism does not always explain Jesus’s crucifixion using a substitute. In The Gospel of Judas, for example, Jesus commissions Judas to turn him over to the authorities so that he will be killed and thereby liberate his soul from the confines of his body. Christian Gnosticism, thus, is not characterized by an alternate narrative so much as an alternate approach that assumes that what had apparently happened—along with the meaning that it supposedly carried—in the Crucifixion was a deception.

3. Simon of Cyrene

A 4th-century bishop named Epiphanius, who ministered in Salamis on the island of Cyprus, reports that there was a teacher from Egypt named Basilides who propagated an idea strikingly similar to the one that appears in The Treatise of the Great Seth, but with a few more details.

According to Bishop Epiphanius, it was Simon of Cyrene, the man who carried Jesus’s cross for him according to the New Testament, who ended up being crucified as Jesus’s substitute. Jesus used his miraculous power to change Simon’s appearance so that he looked identical to himself, while simultaneously changing his own appearance so that he looked like Simon. In other words, Jesus caused something like a switching of their bodies.

The Romans proceeded, in turn, to crucify Simon while Jesus stood at a distance laughing at their ignorance. Jesus was then ushered directly into heaven without dying at all.

4. A Volunteer

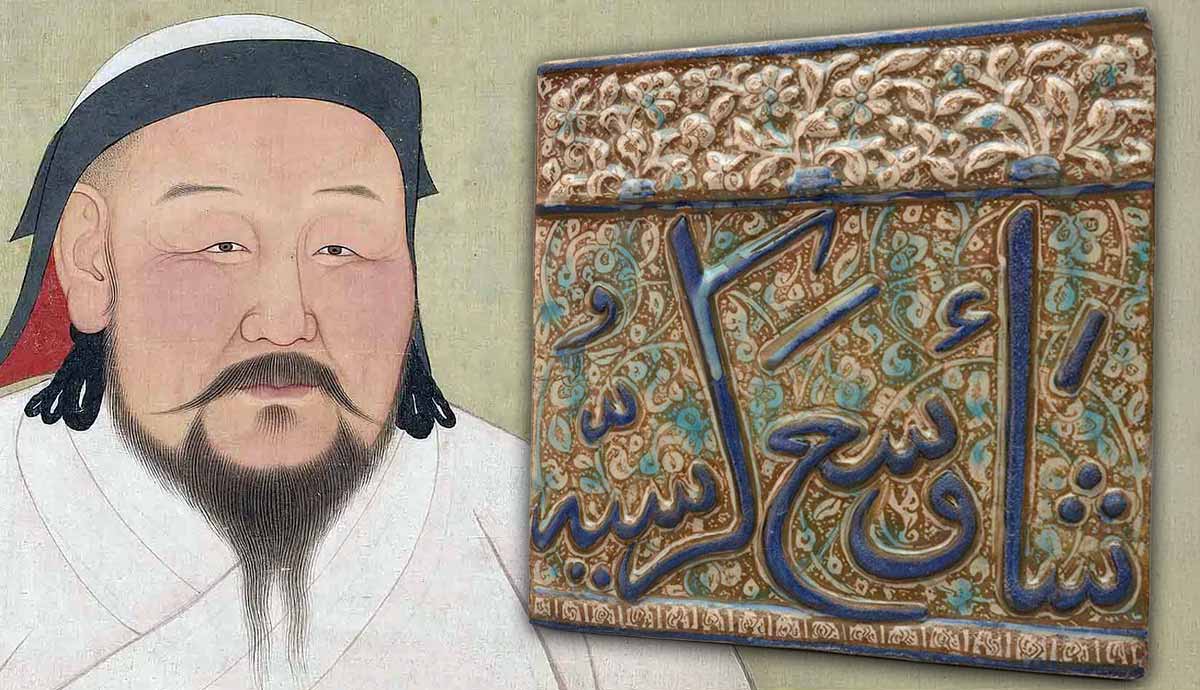

Islam’s holiest book, the Qur’an, famously reports that it only appeared to his oppressors as if Jesus was killed, but in fact, God rescued him and raised him up to heaven. No further details are provided, which has left the door open to a variety of explanations for Jesus’s “apparent” crucifixion. Islam does not have an official, orthodox doctrine on this matter apart from the firm belief that Jesus was not crucified.

The idea that a substitute died in Jesus’s place, however, has been popular in Muslim circles for centuries, beginning with a reference in the Hadiths, which are extra-Qur’anic collections of reports about the sayings and teachings of Muhammad. In a relatively obscure Hadith in one of these collections, Jesus asks for a volunteer from among his disciples who would be willing to die in his place. This would be accomplished by the superimposition of Jesus’s visage onto the disciple. An unnamed young man answers Jesus’s call, and Jesus accepts. A more succinct version of this scenario appears elsewhere in the Hadith as well.

The idea that a victim was selected to bear Jesus’s image and, in turn, be crucified in his stead seems to be rooted in Christian Gnosticism, as the sources discussed above imply. It appears that this interpretation of the crucifixion survived into and through the early Muslim movement. However, though significant religious players found it worthy of passing on, there is something morally troubling about it. Why would—or, rather, should—a bystander or volunteer be executed so that Jesus could escape?

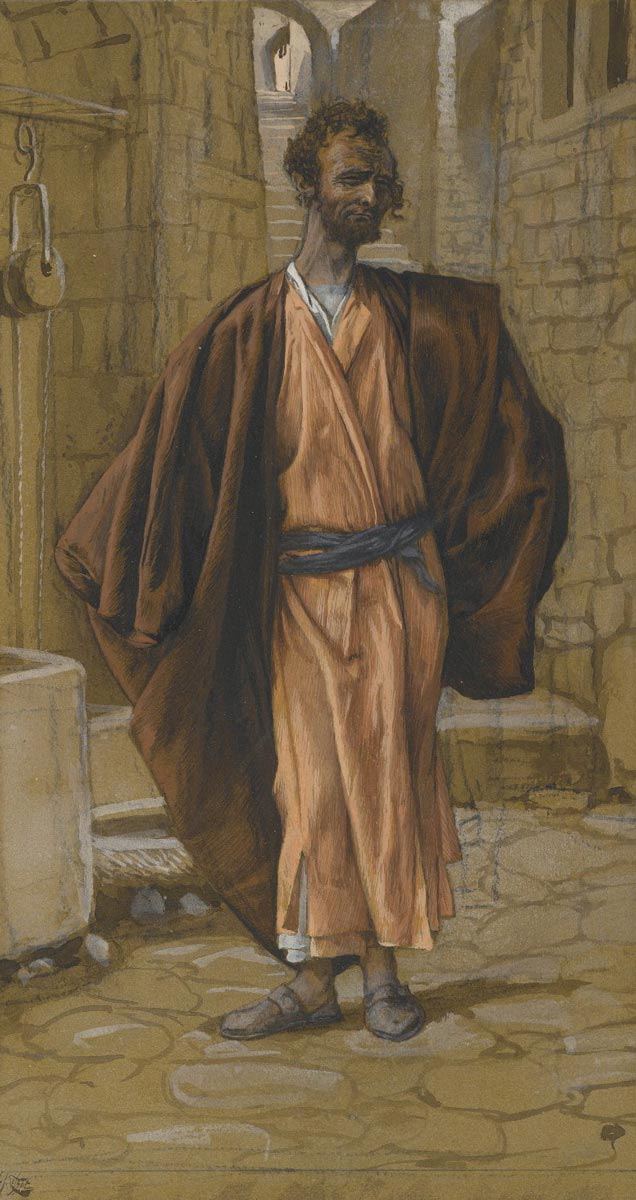

An innovative retelling of the crucifixion story that utilizes this image-casting trope later solved this problem. Instead of an innocent bystander, the victim would be Judas Iscariot, Jesus’s betrayer.

5. Judas

The so-called Gospel of Barnabas (not to be confused with the Epistle of Barnabas) is a medieval, Muslim forgery using the name of one of Jesus’s disciples. It poses as the real story and message of Jesus, revealed by Jesus to correct the twisted version of it that had been propagated by Paul and others who had been, according to this work, deceived. The work is clearly not a serious historical take. However, this is not to say that it is not a clever one.

In this retelling, the famous kiss of Judas never occurs. Instead, upon hearing Judas approaching with the soldiers to arrest him in the garden where he was praying, Jesus runs in fear into the house where his other disciples are sleeping. Seeing that Jesus is in danger, God sends four angels to rescue him, and they bear him out of the house and up to heaven without his disciples’ knowledge.

When Judas enters the house ahead of the soldiers in order to turn Jesus over, God miraculously casts Jesus’s appearance onto Judas. The soldiers then enter the house to arrest this Jesus look-alike, and Jesus’s disciples flee in fear and befuddlement. Judas is then subjected to all of the tortures mentioned in the Gospels while Jesus himself is at rest in Heaven.

Jesus asks God to allow him to reappear on Earth only after hearing his mother believed it was him who had been crucified. He later appears to a portion—but not all—of his disciples. Jesus is angered by his disciples’ quickness to believe that he had been crucified since he had predicted that God would deliver him. Unbelief, thus, is presented as the root of the deception that he had been killed.

Why a Replacement Theory?

The Gospel of Barnabas presents the most detailed replacement theory available and, as such, provides the most colorful background for reflecting on why such theories have been attractive to some.

While in the Gospels the abuses of Jesus are understood to be the unjust treatment of an innocent sufferer, in this telling they become a kind of retribution: Judas suffers what would have been suffered by the one he intended to betray. The text even says that, while the intention was for Judas to die under the whip, God himself preserved him so that he would have to suffer the entirety of the Crucifixion. Justice, on a retributive definition of the word, is served on this account.

This story presents God as a clever tactician. Not only do Judas’s designs fall back on his own head, but Jesus’s accusers also end up as fools. The New Testament presents their designs as unjust and evil. But in The Gospel of Barnabas’s recreation of the story, a dimension of idiocy is added. In the New Testament God is presented as overcoming the injustice and evil of the Crucifixion through the Resurrection. In other words, no amount of leadership competence or executional acumen could have prevented God’s final victory. But in The Gospel of Barnabas God foils the Crucifixion itself by capitalizing on the ignorance and folly of Jesus’s persecutors.

Thus, at stake for the crafters of replacement theories was not merely a curious historical reconstruction, but a different way of understanding how God works in the world.

Subverting Orthodoxy

At the end of The Gospel of Barnabas, the Apostle Paul is singled out as one of those who had been deceived by the notion that Jesus had died and resurrected. This strikes the reader of the New Testament as odd since, according to the New Testament Book of Acts, it was Barnabas who actively welcomed a recently converted Paul into the fledgling Jesus movement when most were wary of him.

However, because it was Paul more than any other person who propagated what would become the standard explanation for Jesus’s post-death reappearances across the northeastern Mediterranean world, opposing this idea would need to discredit him.