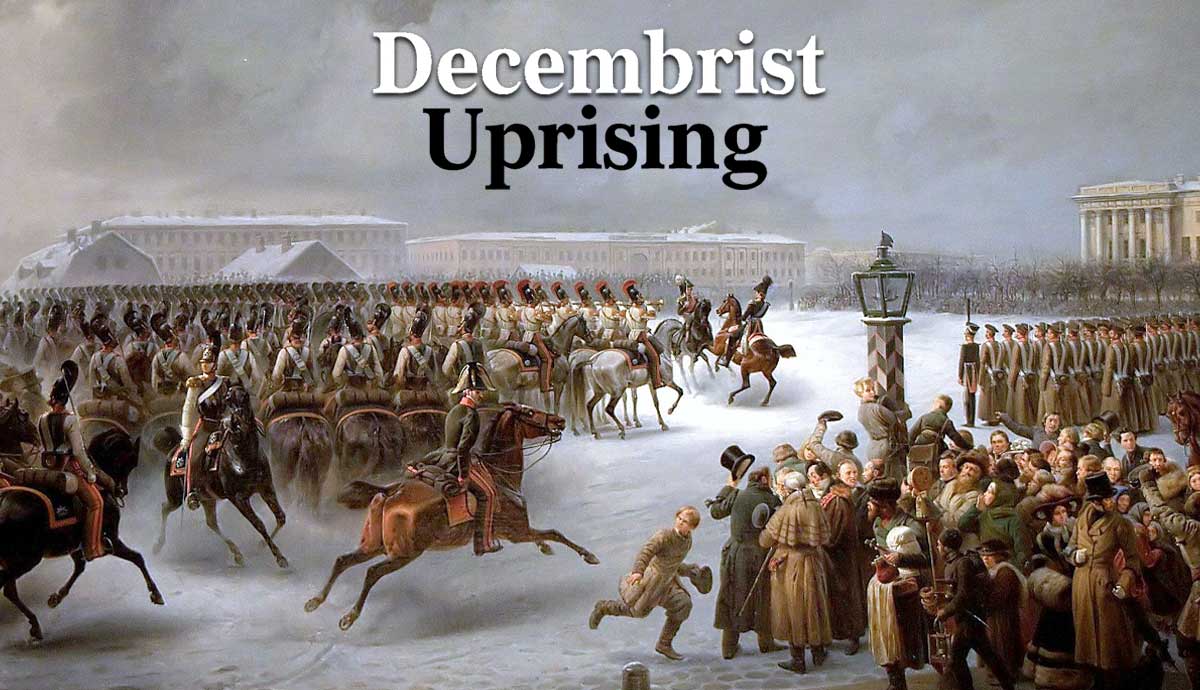

On December 26, 1825, around 3,000 Russian guardsmen staged a demonstration on Senate Square in St Petersburg against the accession of Tsar Nicholas I. They were led by liberal officers who had been conspiring for several years to overthrow the tsarist regime, abolish serfdom, and introduce a constitution. After a tense confrontation for several hours, Nicholas reluctantly fired on the rebels. Hundreds of conspirators were arrested and over a hundred were sentenced to exile in Siberia.

The Revolutionary Spirit

In March 1801, Tsar Alexander I of Russia succeeded his assassinated father Tsar Paul as Emperor of Russia. Educated by the Swiss liberal philosopher Frédéric-César de La Harpe, Alexander came to the throne seeking to introduce liberal political reforms and abolish the notorious institution of serfdom. Alexander’s early reform initiatives were significantly watered down by conservative aristocrats who warned of peasant uprisings.

Alexander’s domestic agenda was further impacted by the outbreak of war with Napoleonic France, but reform prospects improved after Alexander and Napoleon signed the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807. In 1809 Alexander’s chief minister Mikhail Speransky introduced proposals for a constitution inspired by British, American, and French models with separation of powers between executive, legislative, and judicial branches. However, the plans were shelved as tensions began to build between Russia and Napoleon, and in March 1812 Speransky was exiled to Siberia as a French sympathizer.

Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812 famously ended in disaster, and by April 1814 Russian soldiers were triumphantly marching through the streets of Paris. The liberal officers who experienced the freedoms of French society returned to Russia hoping that the tsar would resurrect his reform agenda.

Although Alexander had granted Poland a constitution in 1815 and appointed Speransky to lead administrative reforms in Siberia in 1819, their hopes for meaningful change were dashed as Alexander surrounded himself with conservative advisors including the reactionary general Alexei Arakcheev, who was placed in charge of Alexander’s military colonies. Arakcheev’s administration of the scheme, which intended to turn soldiers into farmers in peacetime and peasants into soldiers in wartime, was widely resented and led to sporadic mutinies.

The Northern Society

In 1816, several Russian Guards officers founded the Union of Salvation, a secret society dedicated to the abolition of serfdom and a constitutional monarchy. The organization was soon dominated by the radical Pavel Pestel, who became its chief ideologue and began agitating for political revolution. In 1818, the Union of Salvation was reorganized into the Union of Prosperity, a more moderate body boasting a wider membership base.

After Pestel was transferred to the headquarters of the Second Army in Tulchin, Ukraine in 1818, the Union of Prosperity was divided between a moderate northern faction in St Petersburg and a more radical southern faction in Tulchin. The Union of Prosperity was dissolved in early 1821 as its more cautious members feared a government crackdown following a high-profile mutiny by the elite Semenovsky Guards. Pestel refused to recognize the dissolution and founded the independent Southern Society.

In 1822, a few leaders including Nikita Muravyev and Prince Sergey Trubetskoy formed the Northern Society in St Petersburg. Although a republican at heart, Muravyev drew up a constitution that envisaged the abolition of serfdom, a constitutional monarchy, and a federal system of 13 states and two provinces inspired by the US Constitution.

The Northern Society became more radical after the poet Kondraty Ryleev was recruited into the ranks in 1823. Although he opposed Muravyev’s constitution and was more sympathetic to Pestel, he proved an effective propagandist and spokesperson for the Northern Society’s cause.

The Southern Society

From Tulchin, Pestel recognized that any successful military uprising had to take place in St Petersburg, the imperial capital. He hoped to cooperate with the Northern Society, but criticized Muravyev’s constitution for being too moderate. He believed that a federal system would encourage fragmentation and considered the land grants Muravyev proposed for freed serfs to be insufficient.

Pestel set out his own political agenda in his unfinished treatise Russian Justice. He envisaged a comprehensive overhaul of Russian society, with each individual entitled to a strip of land sufficient to sustain a family of five. Any surplus land belonged to the state, which could rent it out to wealthier peasants.

In contrast to Muravyev’s federal model, he proposed a strong central government to direct the revolutionary changes, conceding autonomy only to the Poles. While Pestel called for a free press and individual liberty, he also envisaged a temporary dictatorship for up to a decade supported by a secret police to enforce the revolution. Pestel was an admirer of the meritocratic system that had existed in Napoleonic France, and his revolutionary ideas led his critics to label him the “Russian Napoleon.”

In 1824, Pestel travelled to St Petersburg in an effort to reunite the two societies on the basis of his republican ideas, but was bitterly opposed by Muraviev. He returned to Tulchin bitterly disappointed, though the Northern Society became more radical by 1825 as Ryleev assumed a more prominent role.

A Succession Crisis

While Pestel was prepared to overthrow the tsar by military force, members of the Northern Society preferred either to present Muravyev’s constitution to Tsar Alexander, or to await the tsar’s death and demand the changes from his successor.

On December 1, 1825, Tsar Alexander I died unexpectedly at the age of 50 at the port of Taganrog in southern Russia. Since Alexander had no sons, his younger brother Constantine was officially next in line to the throne. However, Constantine, the Viceroy of Poland, was content to remain in Warsaw and had renounced his succession rights in early 1823. This placed Grand Duke Nicholas next in line to succeed Alexander.

Alexander accepted Constantine’s renunciation but kept the matter secret, and Nicholas himself was completely ignorant of the arrangement. As news of Alexander’s death spread across the empire, Russian officers and officials began swearing oaths recognizing Constantine as the new tsar. From Warsaw, Constantine reiterated his renunciation. Nicholas remained reluctant to take the crown and it was only on December 24 after Constantine adamantly refused to go to St Petersburg that he agreed to become tsar. As a result, the Senate and Imperial Guard were scheduled to swear a new oath to Nicholas on December 26 (December 14 in the Old Style Julian Calendar used in the Russian Empire).

By this point, both the Northern and Southern Societies had agreed to the principle of an armed uprising to overthrow the government. However, Alexander’s death took the conspirators by surprise. Ryleev and the Northern Society leaders decided to take advantage of the confusion by refusing to swear allegiance to Nicholas on the 26th and proclaiming Constantine as the true tsar. The Society elected Prince Sergey Trubetskoy as “dictator,” giving him full authority on the day of the uprising.

A Fatal Confrontation

On December 25, Trubetskoy and other Northern Society leaders began informing the commanders of the Guards regiments of their plans. To their disappointment, several refused to join, leaving the conspirators with only the Grenadier, the Marine Guards, and Moskovsky Guard regiment. Although Trubetskoy rapidly drew up grandiose plans to seize the Winter Palace and arrest the imperial family, during the night he was convinced that the uprising was doomed to fail.

On the morning of the 26th, a few of the Decembrist regiments assembled on Senate Square on the banks of the River Neva and shouted “Hurrah Constantine!” Trubetskoy was absent during the appointed hour and instead visited the chief of staff’s office to express his desire to swear his oath to Nicholas, before taking refuge at the Austrian Embassy. In Trubetskoy’s absence, the rebel units, who numbered some 3,000 men, stood around without taking any initiative.

Nicholas was unnerved by the demonstration, but had little desire to ascend the throne upon the bodies of Russian guardsmen. He made several attempts to reach a peaceful resolution and persuade the rebels to stand down. Mikhail Miloradovich, governor-general of St Petersburg and a popular hero of the war against Napoleon, volunteered to parley with the rebels. The Decembrists refused to accept his entreaties, and as he turned back he was shot and killed by Pyotr Kakhovsky, who had been planning to assassinate Nicholas himself.

Although Nicholas had continued to seek a peaceful resolution to the confrontation after Miloradovich’s death, as night approached he was afraid of the defection of loyal troops if the demonstration continued into the following morning. Nicholas ordered his cavalry to ride down the rebels, but the unshod horses struggled to move in the ice and were forced to retreat.

Nicholas made one final effort by dispatching artillery general Ivan Sukhozanet to offer the rebels a pardon if they dispersed, which was refused. Sukhozanet therefore advised the tsar to clear the square with artillery fire. Nicholas was appalled by the suggestion but eventually agreed to do so after being advised that he had no other choice if he wanted to remain on the throne.

While the rebels witnessed three artillery pieces being brought forward, they could not imagine their brethren firing on them. After the insurrectionists ignored a final warning, the deadly muzzles of the cannon burst forth with murderous canister shot. Hundreds of soldiers and civilians were killed and wounded in the ensuing action as the artillerymen continued to fire into the backs of the retreating rebels and the cavalry rode down any units attempting to reform. Large numbers of rebels drowned as cannon balls broke the ice on the frozen Neva.

A Brutal Crackdown

The Northern Society envisaged a simultaneous insurrection by the Southern Society in Ukraine, but any plans for a rising in the south were undermined by Pestel’s arrest on December 25. The Southern Society did not receive news of events in St Petersburg until early January. Pestel’s associates Sergey Muravyev-Apostol and Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin led a few hundred men of the Chernigovsky regiment and occupied a few towns around Kyiv but were eventually defeated by a government force. The ringleaders of the Southern Society were arrested and taken to St Petersburg for questioning.

While Decembrists were rounded up and imprisoned in the notorious Peter and Paul Fortress, Nicholas appointed a special investigative committee whose members included his younger brother Grand Duke Mikhail Pavlovich and secret police chief Alexander Benckendorff. The tsar himself personally questioned most of the Decembrists. Although instinctively conservative, Nicholas was sympathetic to moderate reforms and his charming manner encouraged many of the rebels to share information about the conspiracy.

After the investigation committee completed its work, Nicholas established a special court to pass sentences upon the Decembrists. Almost 600 men were brought to trial, of whom around half were acquitted. Of the remainder, 121 were identified as worthy of the heaviest punishments. Five ringleaders were sentenced to be quartered, while a further 31 individuals were to be beheaded, while the remainder would be exiled to Siberia. Nicholas modified the sentences so that only the five would be hanged, while the 31 would be exiled to Siberia for life.

On July 25, 1826, Kondraty Ryleev, Pyotr Kakhovsky, Pavel Pestel, Sergey Muraviev-Apostol, and Alexey Bestuzhev-Ryumin were hanged on the grounds of the Peter and Paul Fortress. The same day, the first party of exiles began making their way to Siberia in heavy chains.

The First Russian Revolution?

Despite its failure, the Decembrist uprising was a major event in Russian history. The Russian liberal intelligentsia sympathized with the Decembrists and cast Nicholas I as a brutal tyrant. The small group of Decembrist wives who accompanied their husbands to their Siberian exile were celebrated for their loyalty and sacrifice.

Although Nicholas occasionally agreed to reduce the sentences of individual exiles, it was in 1856 only after his death that his son Alexander II granted full amnesty and restored the privileges of the surviving Decembrists. A liberal reformer, Alexander II finally emancipated the serfs in January 1861, although its conditions still imposed heavy burdens on the liberated peasants.

Unlike the conspirators who led palace coups in 18th century Russia, the Decembrists were motivated by wider political ideals rather than personal interests. Their example inspired Russian revolutionary groups in the second half of the 19th century, such as the People’s Will, which assassinated Alexander II’s in 1881.

Following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the Decembrists were celebrated as revolutionary heroes. Yuri Shaporin’s 1953 opera The Decembrists was one of the most popular productions at the Bolshoi Opera, and in 1975 a monument to the five executed Decembrists was erected in the grounds of the Peter and Paul Fortress.

The subject of the Decembrists continues to be of cultural interest in contemporary Russia following the release of the 2019 film Union of Salvation. In accordance with the conservative values of the Russian state, the film depicts the Decembrists as dangerous fanatics who recklessly undermined the state and threatened civil war until Tsar Nicholas took action to restore order and harmony.