The ancient Britons were Celts, in as much as they were speakers of a Celtic language. How did the Celts arrive in Britain? Traditionally, scholars have understood that they arrived in Britain in approximately 600 or 500 BCE, during the European Iron Age. However, what is the basis for this conclusion, and does it really stand up to scrutiny? Is there any evidence of an invasion or even a generally peaceful migration? Or did the Celtic language spread to Britain much earlier in history, as far back as the Bronze Age?

The Traditional Narrative of an Iron Age Celtic Invasion

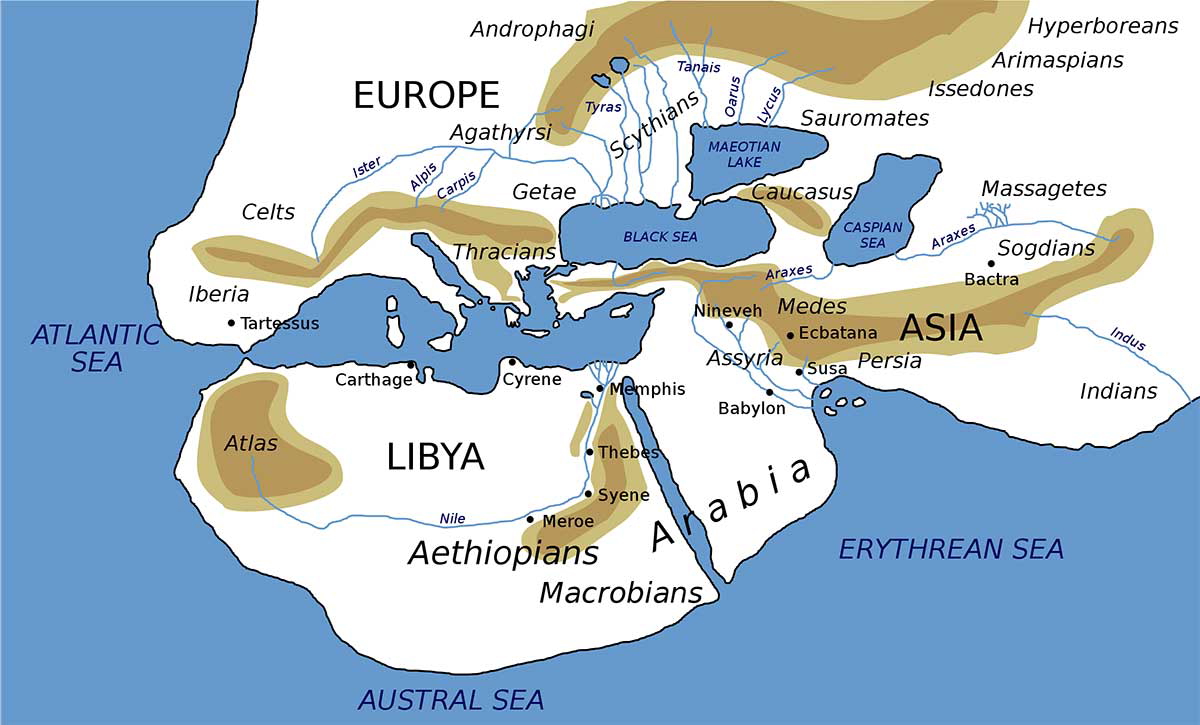

The Celts first appear in historical sources in the writings of the ancient Greeks, starting in the 6th century BCE. These references place them in Gaul, in what is now France. They were also associated with Iberia from an early period. Although no ancient source explicitly refers to the Britons as Celts, there are a number of statements that show that this is what they were understood to have been. Furthermore, the primary common feature of the disparate groups referred to as Celts by the Greeks and Romans was their shared Celtic language family. The Britons belonged to the same language family.

Researchers note that the earliest references to the Celts place them on the continent. Furthermore, there is no trace of mass migration out of Britain. Hence, the traditional idea is that the Celts migrated to Britain from Gaul in the Iron Age, in c. 600 to 500 BCE.

An Alternative Bronze Age Invasion

However, in recent years, archaeologists have argued that there is no good evidence of a large-scale migration from the continent to Britain at the start of the Iron Age. For this reason, as historian Paul Elliott explained, archaeologists have looked further back in time for the evident Celtic invasion. One potential period is in the Early Bronze Age, when the Bell Beaker people arrived in Britain and replaced nearly all of the native population.

Other archaeologists prefer a different period. They place the Celtic arrival in the Middle to Late Bronze Age, somewhere between 1550 and 750 BCE. A genetic study in 2021 demonstrated that there was a particularly notable influx of people from the continent in the period between 1000-875 BCE. They proposed this as a plausible vector for the arrival of early Celtic languages into Britain. In comparison, they found that there was relatively little genetic evidence of migration into Britain from the continent in the Iron Age.

Evidence Against a Bronze Age Origin

This evidence for a Celtic invasion or migration into Britain in the Bronze Age has caused this theory to become quite popular. Nevertheless, it is not without its problems. As the Encyclopedia Britannica notes, the Insular Celtic languages, that is, the Celtic languages of the British Isles, display a number of characteristics that seem unique to the Celtic language family. Britannica then notes the following:

“Some scholars have argued that these features may have resulted from the presence of a large non-Celtic substratum in the British Isles. Because it is hardly likely that the Celtic invasions of those islands began much before 500 BCE or that the invaders exterminated the existing inhabitants, such a possibility cannot be denied.”

According to this quotation, the spread of Celtic languages to Britain is “hardly likely” to have begun before 500 BCE. One key reason is that ancient Brythonic and ancient Gaulish were very similar languages.

Brythonic was the Celtic language of the ancient Britons, while Gaulish was the Celtic language of the Gallic tribes of Gaul. A number of early Roman writers acknowledged that their languages were very similar. Although we do not have any extensive texts from pre-Roman Britain, some scholars believe that Brythonic in the 1st century BCE was mutually intelligible with Gaulish. Indeed, the statements of the Roman writers point in that direction.

This being the case, is it really reasonable to conclude that the Celtic invasion or migration of Britain occurred as far back as c. 1000 BCE? Remember, Britain was not connected to Gaul by a land bridge. The common continental phenomenon of one language gradually transitioning into another one among neighboring countries would not have occurred. Although trade existed between Britain and Gaul, there was still an entire sea separating the common people.

Consider how distinct Cornish and Welsh have become after the two peoples were separated in the 7th century CE. Surely, if Celtic languages were brought to Britain as early as 1000 BCE, they would have diverged significantly by the 1st century BCE.

Evidence for an Iron Age Migration

Let us return to the idea of an Iron Age Celtic invasion of Britain. Is it really true that there is no evidence of any substantial migration in this period? What does the latest research reveal about this topic?

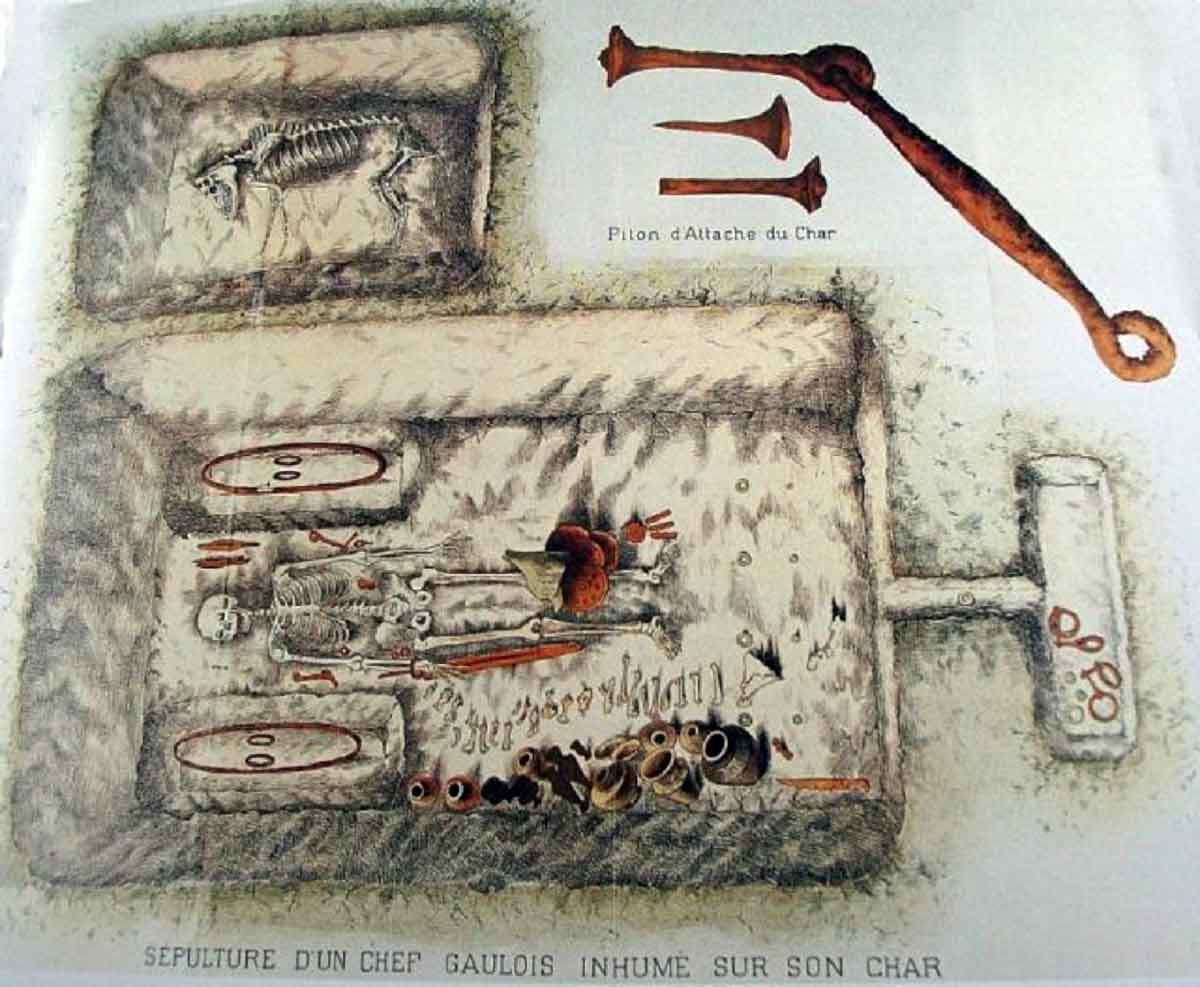

One famous example of Celtic culture in Iron Age Britain that appears to have resulted from an invasion or migration is the Arras Culture of Yorkshire. This culture used square grave barrows, many of which have been found with chariot burials. The practice of chariot burials is characteristic of the Le Tène Culture among the continental Celts of the Iron Age, starting in c. 500 BCE. The use of square barrows is also characteristic of the La Tene Celtic culture, even without the presence of a chariot.

The earliest chariots found in the Arras Culture date to c. 400 BCE. Since this is after the earliest examples in Gaul, this naturally indicates that the culture was brought from Gaul to Britain.

As Oxford Reference states: “The square barrow tradition in England has been characterized as a key part of the Arras Culture, which may have been introduced to eastern England by settlers from France.”

This archaeological evidence clearly points towards some type of migration, whether violent or not. However, it has usually not been considered good enough evidence for an Iron Age Celtic invasion of Britain. Why not? The answer is in Peter Elliott’s comments, which were referenced earlier. While there is evidence for some migration, the Arras Culture was limited to only one part of Yorkshire.

Significantly, recent research points to a different conclusion. As the Oxford Reference highlights, the square barrows “are found mainly in Humberside and the East Riding of Yorkshire. An increasing number, however, are being recognized in other parts of England.”

Indeed, satellite imagery has found them as far south as Essex, while archaeology has revealed one chariot burial as far north as Newbridge, Scotland. Incidentally, this latter find is the earliest known chariot burial in Britain, dating to c. 450 BCE.

Harmonizing With the Genetic Evidence

Based on this evidence, some scholars today are arguing that Britain’s early Iron Age did, in fact, see a large-scale migration. One archaeologist argued that the first-generation immigrants may have arrived over a much larger area, but the practice of chariot burials only endured after that first generation in Yorkshire’s Arras Culture.

The aforementioned genetic study indeed noted that there is less evidence of migration in Britain in the Iron Age compared to the Bronze Age. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the migration, which evidently did occur, could not have spread the language there. After all, the Roman invasion of Gaul did not actually involve a mass migration of Romans to the land, yet the language of the Romans ended up replacing Gaulish.

Those engaging in chariot burials were of the elite class, not the common people or traders. Therefore, it is evident that those who brought the square barrow chariot burial culture to Britain must have been in positions of power. Consequently, even without substantially changing the genetics of Britain, they could have had a powerful impact on the language.

Was There Really a Celtic Invasion of Britain?

In conclusion, what does the evidence really suggest regarding the Celtic invasion or migration to Britain? It is clear that this issue continues to be a controversial topic, and it is far from settled. Genetic research supports the conclusion that there was substantial migration into Britain from the continent in c. 1000-875 BCE. It is very likely that the inhabitants of Gaul at that time were already Celtic speakers, meaning that they must have brought Celtic to Britain. However, the strong similarities between Brythonic and Gaulish as late as the 1st century BCE argues against the two languages separating so far back.

Evidence from the Arras Culture provides clear indications of a migration of an elite class from Celtic Gaul to Britain in the Iron Age, in the 5th century BCE. However, recent research shows that this migration must have been much larger than originally thought. Furthermore, given the evident status of these arrivals, they may have been in a position to impact the language of the island disproportionately to their genetic impact.