When Edward Said published his book Orientalism in 1978, his insights shattered previous notions of East-West relations and caused late twentieth-century thinkers to reexamine the motivations and messaging behind everything from popular literature and art to advertisements and school textbooks. However, some responses since the book’s publication have looked critically at its arguments and have labeled its application as overly broad. Should Edward Said be considered the father of a thought revolution, or is his version of Orientalism a reductive oversimplification of a complex issue?

About Edward Said and Orientalism

Edward Said might be a household name in global academic and political circles, but that was not always the case. He was born in 1935 in West Jerusalem in British-ruled Mandatory Palestine but also spent part of his formative years in Egypt and the United States. After obtaining his PhD in English literature, he became a professor at Columbia University, a prestigious position that afforded him the time and resources to conduct research and develop his own theories surrounding what he had witnessed throughout his life.

Said described in his book the active, rather than passive, construction of an entire system of self-sustaining knowledge which established and then reinforced the moral, technological, cultural, and intellectual superiority of the West as compared to its neighboring Near East countries, often referred to as the Orient. This term often referred to a number of diverse North African or Middle Eastern geopolitical entities, but these were frequently conflated in literature and the arts to be presented as one land, stripping cultures of their unique histories, customs, and identities and replacing them with unfavorable generalizations.

The Roots of Orientalism

A number of social, political, and economic factors influenced a growing interest in the East during the 19th century. The ease of safety and travel increased, leading to the emergence of the first organized tour groups and a reconfiguration of the popular European Grand Tour to include stops such as Turkey and Egypt. Views of the Ottoman Empire continued to evolve from those of a threatening adversary to a trade partner, a shift that had begun in the 18th century. The transmission of decorative motifs birthed from Napoleon’s campaign into Egypt infiltrated fashion, interior design, and furniture throughout France. The East was at once feared and admired, and Said notes that it is possible to simply study or appreciate the East for the qualities that make it unique. However, the West’s construction of Orientalism drew on these differences as the cornerstone for a structure of power and oppression as a means of controlling what they saw as a very valuable set of resources.

It is important to note that Orientalism can be seen as both a cause and a product of imperialism. As dominant forces wished to expand their empires, they felt justified in doing so based on the view that the lands of their desire were populated by people who were sexually immoral, lazy, attached to antiquated customs, and, therefore, in need of European intervention. Paintings, prints, travel diaries, literature, and plays that were based on first-hand accounts of colonized lands emphasized a sense of exoticism and mystery surrounding the East. These representations were taken as fact by the populations of Europe and North America, serving to bolster the stereotypes already in place.

Is All Art Depicting the East Considered Orientalist?

Some have argued that conscious participation in transmitting a political agenda is necessary in order to classify a particular work of art or literature as Orientalist. Edward Said disagrees with this line of thinking and, as stated by Mary Margaret DeMaria Smith in her essay in Cleopatra: The Sphinx Revisited, “According to Said’s theory of Orientalism, to be an Egyptologist, a writer of Egyptian stories, or a painter of Egyptian subjects implicates one in the production of ideas that justify domination of Egypt by French and then British colonial powers.” But can an artist, for example, create a painting representing some aspect of Eastern culture or history that might be considered appreciation rather than Orientalism?

A group of 19th-century painters known for depicting antiquity provides an interesting case study for this discussion. Artists including Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Edward Poynter, and Edwin Long created naturalistic genre scenes set in Ancient Egypt, Syria, or Palestine. These artists relied heavily on recent archaeological finds as well as their own careful study of museum objects to recreate compositions that were as close to historically accurate as possible.

It could be argued that these artists’ efforts were aimed at connecting contemporary viewers with the East to communicate that the modern West and ancient East were actually more alike than different, despite cultural contrasts and their vast temporal separation. Perhaps they wanted 19th-century Europeans to see that grief, celebration, entertainment, and shared meals transcend time and space. In response, Said might have countered that any message about the East communicated by these white, Western European men was influenced by their existence in a society of colonizers, not the colonized.

The Other Side of the Coin: Orientalism’s Detractors

One outspoken opponent of Said’s version of Orientalism is historian John MacKenzie. In his 1995 book Orientalism: History, Theory and the Arts, he draws on 19th-century art to challenge many of Said’s arguments. MacKenzie claims that North Africa and the Middle East were frequent subjects of paintings because these areas were easily accessible and provided a wide range of inspiration with their varied religions, topographies, archaeological remains, and cultures. He notes that there was not an influx of European artists to other more directly controlled imperial territories, and, thus, representation of a subjugated people should not be considered a primary motive behind many Orientalist works, nor was there any evidence that the collectors of these works were purchasing them with the intent to wield imperial power.

MacKenzie also finds fault with the idea that the Orient is portrayed negatively in art and insists that these connotations are a 20th-century construct that does not reflect the paintings’ original reception. Many images of markets and bazaars, he claims, were not intended to portray a land that was stuck in an outdated past and in need of technological advancement but instead were images conveying the lost art of craftsmanship and connoisseurship still present in the production of goods in the East.

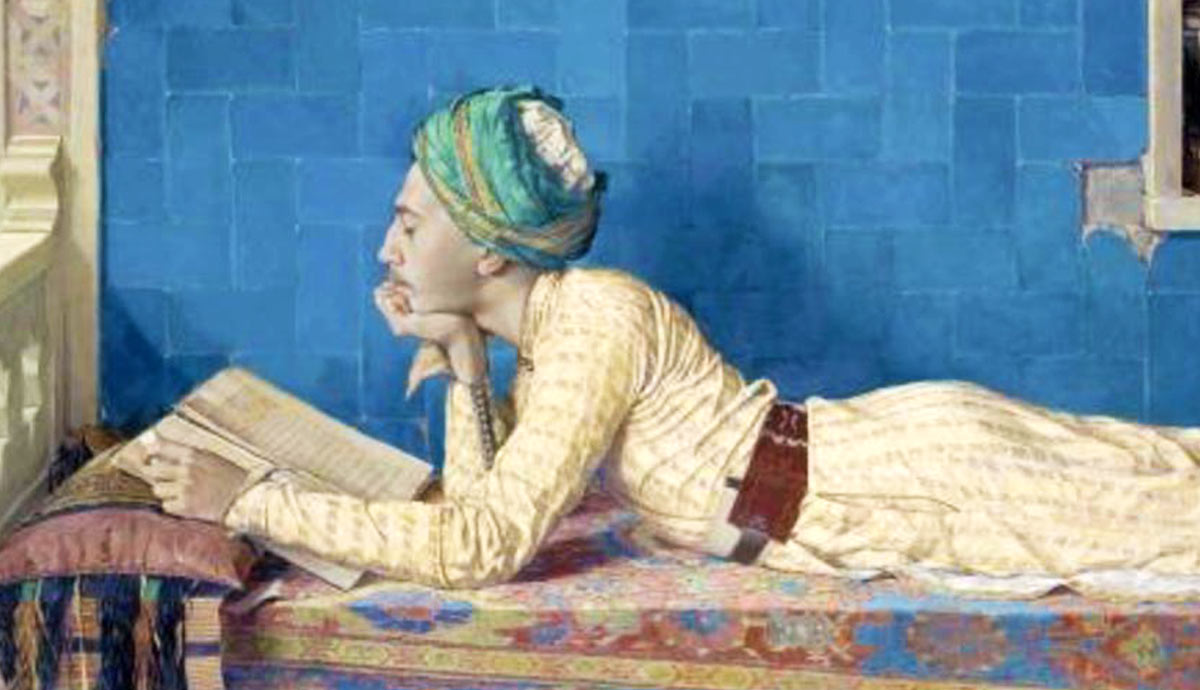

The author also disputes the idea that messages of laziness or idleness pervade Oriental images. MacKenzie believes many of these paintings actually portray respect for literacy and education, appreciation of the arts and literature among Eastern cultures, and piety that was to be admired. He states in his book, “Far from offering an artistic programme for imperialism, they were finding in the East ancient verities lost in their own civilisation. Many of them set out not to condemn the East, but to discover echoes of a world they had lost.”

The Dangers of Stereotyping

MacKenzie’s most direct attack on authors such as Edward Said and Linda Nochlin is that they are not, in fact, historians at all. That is not to say that they are not brilliant minds or to call them wholly uninformed, but rather he makes the argument that imperial attitudes across Europe and North America varied widely, and these authors ascribed only one attitude across several continents and countries. MacKenzie also notes that the political leaders of the era likely had very different motivations than did the art world.

Additionally, thoughts about imperialism underwent quite a notable evolution throughout the century from 1800 to 1900, and the claims made by Nochlin, Said, and others do not take that evolution into account. In short, MacKenzie summarizes by saying that it is unfair and counterproductive to cherry-pick and combine artists from different locations and points in the 19th century and to portray them as locked into one set of racial and imperial assumptions.

Edward Said and Orientalism: Both Revolutionary and Reductive?

As with any school of thought, there is much to be gained from viewing visual culture through a postcolonial lens, but scholars like John MacKenzie remind us of the perils of doing so. In what may feel like a trite conclusion, Orientalism can be considered both revolutionary and reductive. Before the work of Edward Said and the many authors who have built upon his studies since the 1970s, cultural awareness of negative portrayals of the East was not commonplace in scholarly discussions. The power dynamics that existed in the 19th century between empires and colonies should not be discounted when discussing the era.

At the same time, there is reason to question the concept’s extensive use to explain the intent behind nearly all visual and written culture from the 18th century onwards. While it is valid to believe that effect is as important (if not more important) than intent, we do a disservice to creators when we ignore their intent altogether, particularly when our assumptions sometimes contradict the overtly stated meaning of their work.