The term “cryptid” was coined by John E. Wall, an enthusiastic researcher within the highly disputed field of cryptozoology—the study of animals whose existence is hitherto unproven by science. By definition, mythical creatures are not real. Yet so-called Cryptids (literally: “hidden creatures”) have captivated the human imagination for millennia, featuring prominently in folklore and urban legends, and inspiring numerous reported modern “sightings.” While cryptozoology only emerged as a distinct field of study in the 20th century, stories of fantastical beasts—of sea monsters, giant humanoid apes, and blood-sucking reptilians—have existed for centuries. Despite the wealth of scientific evidence debunking the existence of mythical creatures, contemporary belief in cryptids persists, fuelled by anecdotal reports, popular culture, and online speculation.

1. Bigfoot

The legend of Bigfoot, or Sasquatch, extends far back into the early history of North America. Described variously as a 6-10 foot tall, towering hominid ape-like creature, the name “Sasquatch” originates from the native Salish word for “wild man.”

European folklore is rich with stories of “wild men” living on the fringes of society, in woods, forests, and the wilderness. As Europeans made their way to North America it is more than likely that such tales traveled with them. Eventually, this led to the idea of Bigfoot. In 1811, David Thompson, a British explorer, and trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company, was credited with discovering what many believe to be the first documented Bigfoot footprints near modern-day Alberta, Canada.

However, despite countless expeditions and investigations, hard evidence for the existence of bigfoot remains elusive. The famous Patterson-Gimlin film (1967) of Bigfoot wandering through the Six Rivers National Forest in Northern California has been widely debunked. Photographs of enormous footprints remain inconclusive, while DNA analysis of hair samples attributed to Bigfoot have been shown to belong to other animals.

Nonetheless, thousands of sightings and personal testimonies have been reported across the United States and beyond. Native American folklore abounds with Bigfoot-like creatures, some describing them as giant, hairy, bipedal beasts, while others portray them as supernatural, spiritual beings that can appear and disappear in the blink of an eye.

In 1977, American Folklorist David Hufford speculated that “large hair-covered Bipeds” such as the illusive Bigfoot might actually exist. With anecdotal evidence such as sightings, testimonies, and folklore forming the foundation of the Bigfoot mythos, it appears that the “truth” of the existence of Bigfoot is a matter of faith rather than fact (Milligan, 1990).

2. The Loch Ness Monster

The Loch Ness Monster, affectionately known as “Nessie,” is one of the most famous cryptids of all time. Depicted as a long-necked, aquatic plesiosaur-like creature, Nessie is believed to dwell in the deep waters of Loch Ness, Scotland.

Located in the Scottish Highlands, Loch Ness is the largest body of fresh water in the British Isles. Stretching close to 25 miles (40km) long and approximately one mile (1.6km) wide at its widest point, Loch Ness is extremely deep. Its sheer vastness has fueled speculation that a mysterious creature lurks in its shadowy depths for at least 1,400 years.

One of the earliest references to the legend of Nessie is connected to Saint Columba, a 6th-century Irish Christian missionary. According to The Life of Saint Columbia, written by his 7th-century biographer, St. Adamnan, on his travels through Scotland Columba encountered a group of men near the loch burying a friend that had been attacked and killed by a giant “water beast.” Columba ordered one of his fellow monks into the water to investigate, at which point the terrible beast emerged. Saint Columba made the sign of the cross and compelled the beast to “come no further!” Terrified, Nessie fled the scene. The encounter marks the first written testimony of the Loch Ness Monster.

By the 18th century reports of “leviathans,” “serpents,” and “water beasts” in Loch Ness had become widespread. By the 1930s, “Nessie Mania” had taken hold, fueled by newspaper reports and the efforts of famous figures such as Aleister Crowley to popularize the myth. As tales of Nessie spread far and wide, an influx of tourists and monster hunters flocked to Loch Ness.

Today, while no convincing evidence of the mysterious creature has ever emerged, the legend of the Loch Ness Monster endures, bolstered by a thriving Nessie-based tourist industry and continued interest in the possibility of a mysterious monster lurking in the depths.

3. Chupacabra

Dead sheep and farm animals found dead, with puncture wounds, drained of blood—the perpetrators? A fierce and mysterious creature with glowing red eyes and large razor-sharp fangs. While tales of similar grizzly livestock killings by supposed vampire-like creatures in the Americas date back to the 1960s, the legend of the Chupacabra first came to widespread attention in 1995 in Puerto Rico.

Soon after, reports of livestock killings in comparable circumstances began to emerge in Mexico, Nicaragua, Chile, Brazil, and the Southwest United States. One possible explanation links these events to severe droughts that affected these regions between 1995 and 1996. Losing their natural prey to drought, wild predators may have turned to livestock to survive. Many noted that coyote attacks can result in uneaten victims with puncture wounds, and that, in the context of drought, animal carcasses quickly dry out.

While accounts of the mysterious Chupacabra vary they share one central feature: the creature preys on farm animals and drains their blood. The name itself translates literally from the Spanish as the “goat sucker.” In terms of a solid description, some describe a dog-like beast with fangs and red eyes. Others claim that the Chupacabra is bipedal. It has been portrayed as furry in some instances and reptilian with a spikey backbone in others. Most accounts converge on the image of a four to five-foot tall creature with powerful short legs, large red or black eyes, fangs, and either spikes down its back, or small bat-like wings.

One intriguing theory for this popular description, proposed by folklorist Benjamin Radford, suggests that early reports of a reptilian bipedal Chupacabra with glowing red eyes were influenced by that alien creature in the 1995 sci-fi horror movie, Species—the popular release of which conceded with the first Chupacabra sightings.

Nonetheless, regardless of its origins or physical form, the Chupacabra has become a global phenomenon. In less than two decades, the Chupacabra has cemented its place in popular culture, joining the ranks of popular cryptids such as Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster as a globally recognized icon of cryptological mystery and folklore (Radford, 2011).

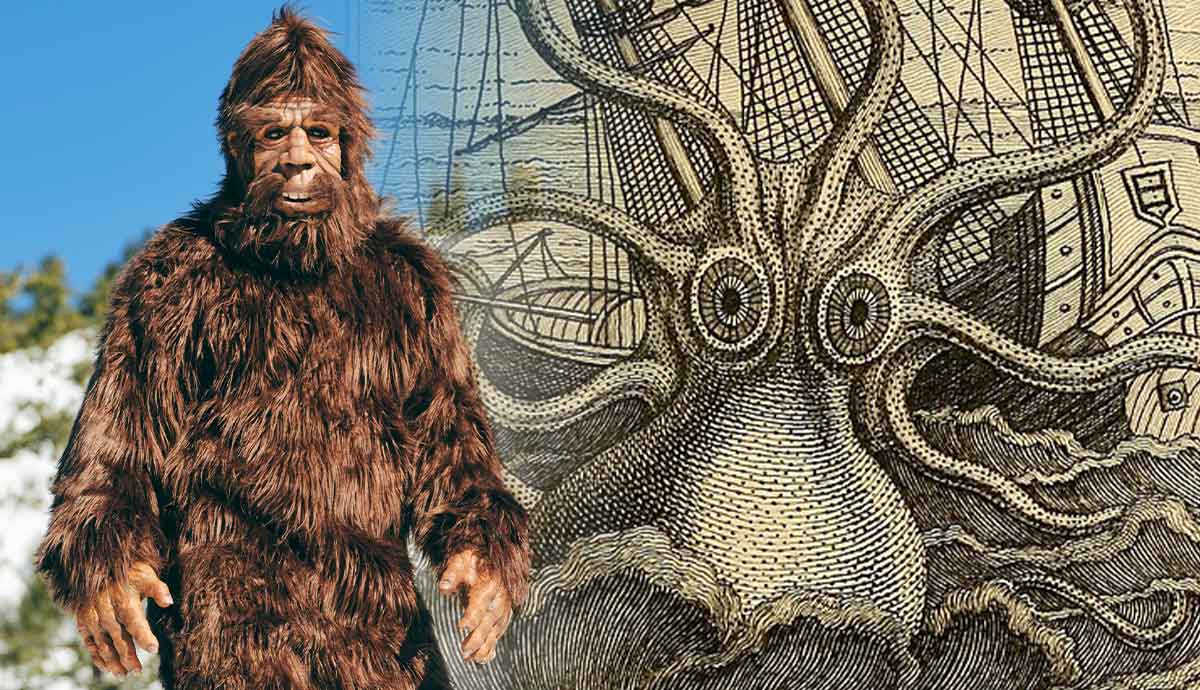

4. The Kraken

The infamous Kraken has long captured the popular imagination as a ship-wreaking menace of the deep. Described as an enormous cephalopod-like, “giant squid,” the Kraken is said to lurk in the depths of the North Sea between Norway, Greenland, and Iceland. In Scandinavian folklore, the Kraken is also known as the Krake, Krabben, or Horven. Legendary accounts portray its colossal size as rivaling that of a small island, its arms as thick as ship masts, and its tentacles capable of wrecking entire vessels.

Historical references to monstrous cephalopods date back to antiquity, with Pliny providing the first known European accounts. However, perhaps the most vivid early report of the Kraken comes from Hans Poulsen Egede, a Danish-Norwegian missionary who launched a mission to Greenland in 1734. Egede is said to have encountered a terrifying “sea serpent” off the coast of Greenland, “longer than our whole ship”—now widely believed to have been some sort of giant squid.

Further accounts were compiled by the bishop of Bergen, Erik Pontoppidan, in his Natural History of Norway (1755). Drawing on reports from sailors and fishermen, Pontoppidan characterized the Kraken as resembling a “vanishing island” and suggested the creature to be a “polype” (octopus, squid) or “of the starfish kind” (White, 2004). His descriptions fueled fascination and fear in equal measure.

In modern times, the Kraken moved from folklore to a staple of popular culture. It has featured in literature such as Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851), movies such as Clash of the Titans (1981) and Pirates of the Caribbean (2006), and it has even become a brand of alcoholic drink, Kraken Black Spiced Rum.

The Kraken myth likely stems from sightings of the real-life giant squid (Architeuthis dux), a deep-sea dwelling squid that can grow to an estimated 12-13 meters (approx. 40 feet) long. Despite its size, very little is known about the giant squid’s behavior and whereabouts. The first images of one in its natural environment were only captured in 2004.

Curiously, it appears that the legend of the Kraken inspired scientific interest in the giant squid, rather than the other way around. Even today, neither scientists nor cryptozoologists can entirely dismiss the possibility that an undiscovered giant cephalopod fitting the Kraken’s description might still lurk in the deepest depths of the ocean.

5. Tasmanian Tiger

The last known surviving Tasmanian Tiger (Thylacinus cynocephalus), also known as the Thylacine, or Marsupial Wolf, died in 1936 in a zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. A large carnivorous marsupial that hunted kangaroos, small rodents, and birds, the Thylacine had short, dense yellowish-brown fur, pointy ears, a large powerful jaw, and a long stiff tail. It earned the nickname the “Tasmanian Tiger” due to the existence of 15 to 20 dark stripes across its back.

During prehistoric times, Australia was home to a variety of carnivorous marsupials, from the early Miocene Thylacinus maknessi to the smaller, early Pliocene Thylacinus yorkellus of South Australia. Thylacinus cynocephalus was the last surviving member of the family genus to survive in modern times.

The prevailing theory about Thylacine extinction in mainland Australia suggests that it disappeared no longer than 2,000 years ago. Likely due to competition with dingos and potentially due to the pressure of human hunting. Aboriginal rock paintings of Thylacine-like animals have been found from Western Australia to the Northern Territory.

In Tasmania, where Dingos were absent, Thylacines were driven to extinction by European colonizers who hunted them, destroyed their habitat, and generally regarded them as pests. When the British colonized Tasmania in 1803, there were an estimated 5,000 Thylacines in the wild. The perceived threat to British livestock (sheep) led to widespread persecution, as rewards and bounties were offered for kills. By the early 20th century Tasmanian Tigers were on the brink of extinction.

Although the last known captive Thylacine died in 1936, reports of sightings have persisted. Some scientists believe that small populations may have existed for decades after the species was declared extinct, with recent scientific modeling based on credible sightings indicating the possibility that Thylacines may have survived until as recently as the 1980s.

However, despite widespread scientific consensus that the Tasmanian Tiger is extinct, the search for “living Thylacines” continues. Groups like the Thylacine Awareness Group of Australia, undeterred by the disinterest of professional scientists, continue to pursue sightings and investigate reports. Against the odds, modern amateur research into the Tasmanian tiger has shifted into the realm of cryptozoology.