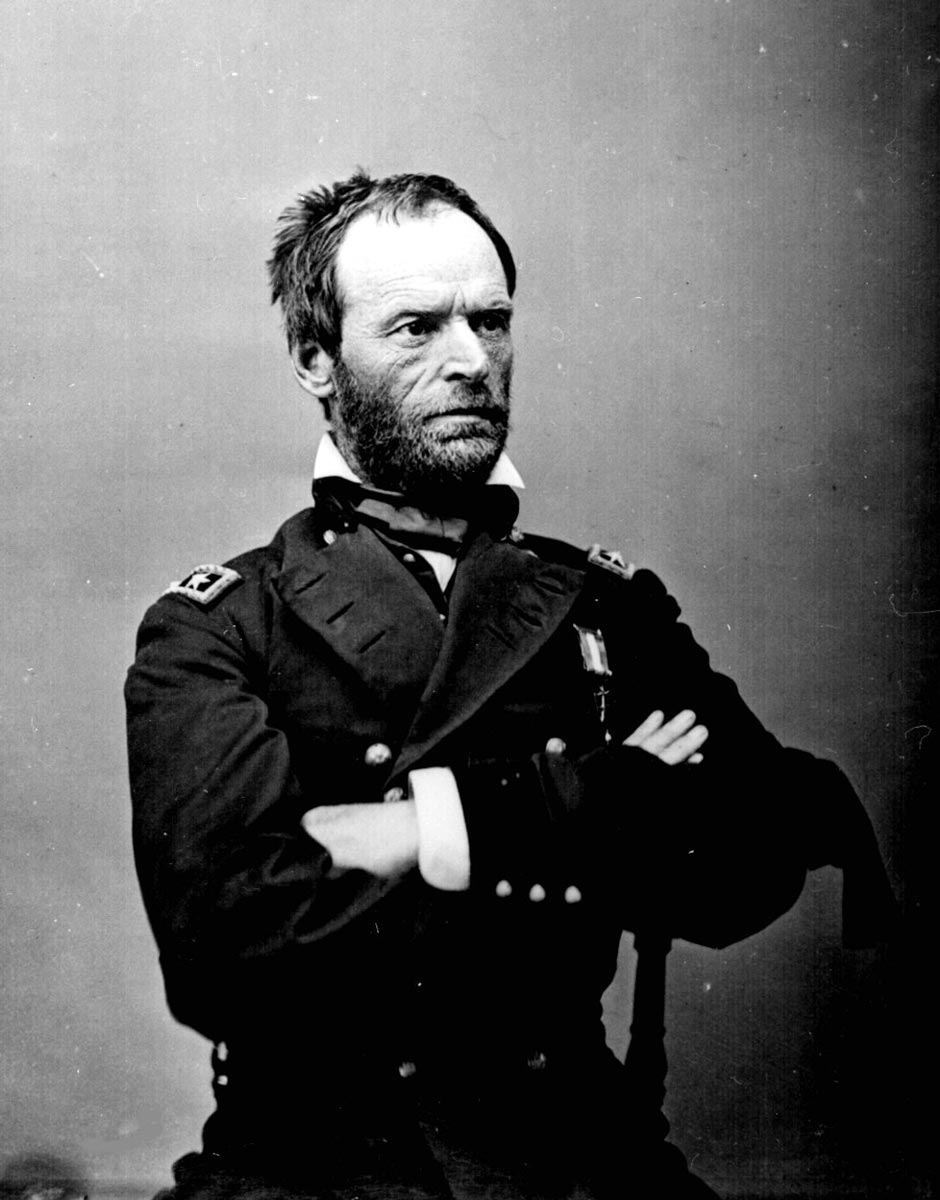

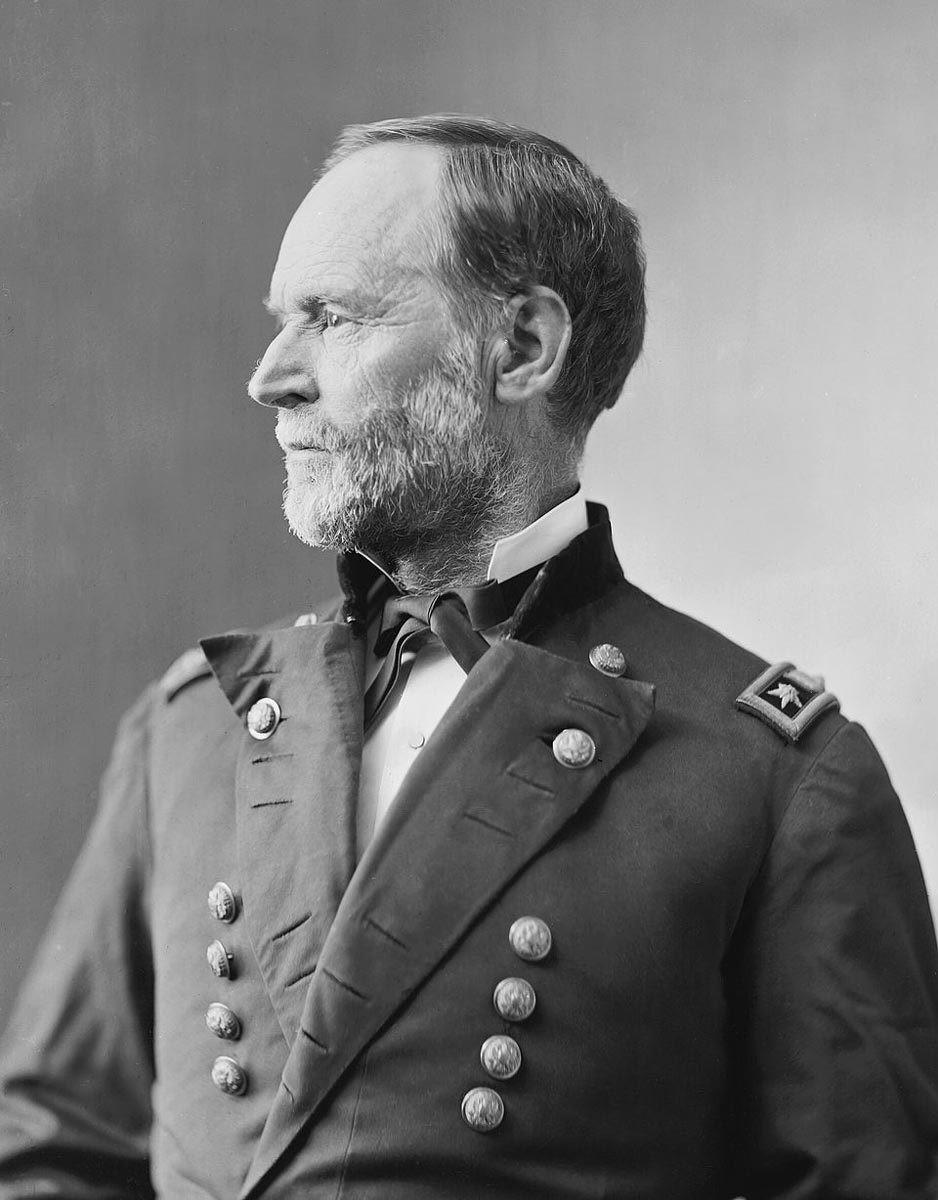

William Tecumseh Sherman was one of the most important Union generals of the Civil War. Sherman helped turn the tide early in the war with victories in the Western Theater and later with his infamous March to the Sea. After the war, he played a key role in the Reconstruction, served as commanding general of all US forces, and remained an influential voice in American affairs until his death. Sherman’s legacy remains one of the most powerful in American military history.

Early Life

William Tecumseh Sherman was born in Ohio in 1820 to Charles and Mary Sherman. When Sherman was only nine, his father died of typhoid fever, leaving his mother to care for eleven children. Sherman was sent to live with a neighbor, Thomas Ewing, a future US Senator from Ohio. Ewing sponsored the young Sherman’s application to the US Military Academy at West Point when he was just 16 years old. He wasn’t a top student academically, but stood out for his practical knowledge and leadership skills.

Graduating in 1840, at the age of 20, Sherman was commissioned as an officer into the artillery and served in Florida during the Seminole Wars before being sent to California during the Mexican-American War in 1848. While he didn’t see as much combat as other officers, his time out West gave him experience in the logistics of warfare, skills he would later use on his infamous “scorched earth” campaign across the American South.

It was during this war that Sherman met another junior officer, Ulysses S. Grant. The friendship between the two would become crucial in the conflict to come. After the war, he briefly left the army to work as manager of the San Francisco branch of the Bank of Lucas, Turner & Co. Sherman quickly found that civilian life did not suit him. In 1859, he became the first superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy, now known as Louisiana State University (LSU).

The Western Theater of War

After several Confederate states seceded from the Union in 1861, Sherman resigned his position as superintendent. He initially did not rejoin the army in defense of the Union. He felt politicians had made a mess of halting secession, famously saying to his younger brother John, a Congressman from Ohio, “you politicians have gone and got things in a hell of a fix.” Sherman spent the next year as a civilian in St. Louis. When the Civil War broke out, Sherman rejoined the Army and was quickly assigned to key commands in the Western Theater.

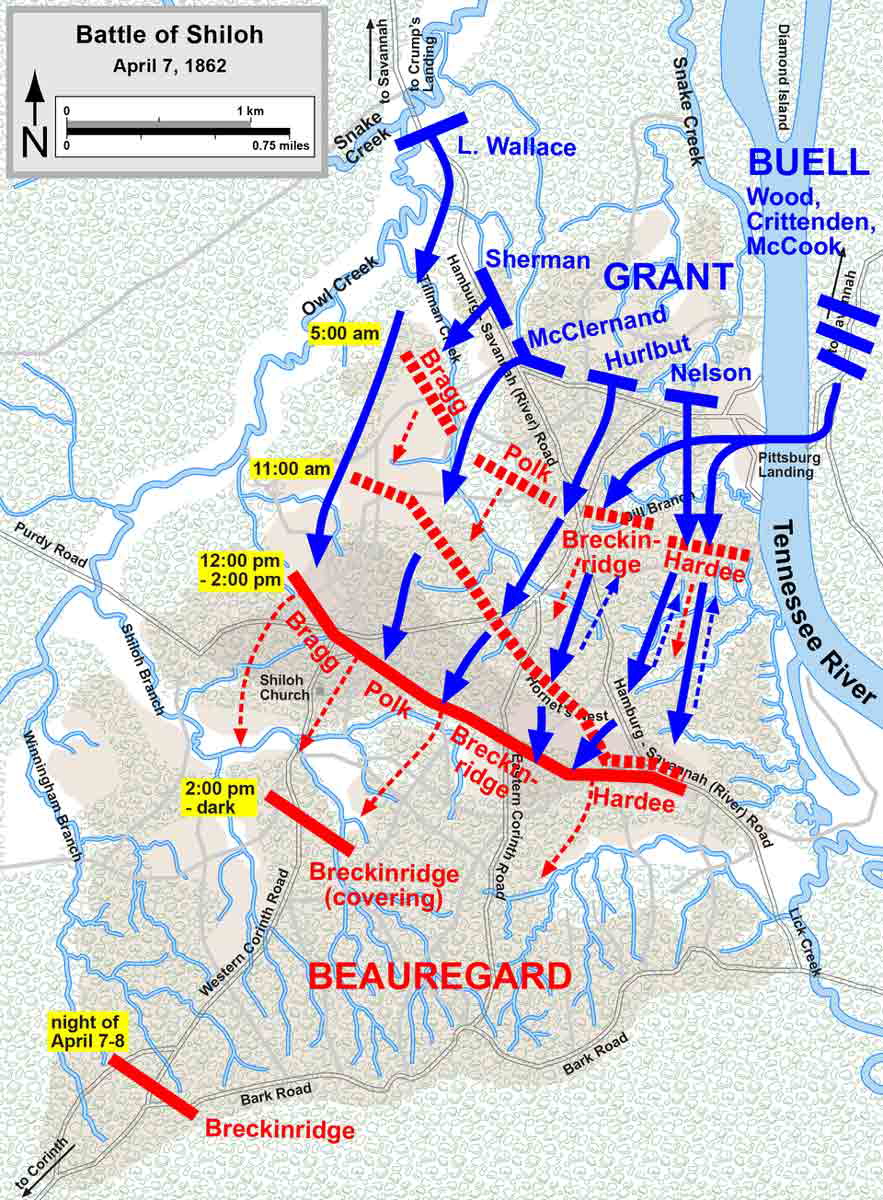

Working closely with his old friend Ulysses S. Grant, he helped secure major Union victories at battles like Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga. At Shiloh in 1862, Sherman’s leadership under fire helped prevent a total Union collapse during a surprise Confederate attack. A year earlier, Sherman was battling severe mental stress as a corps commander in Kentucky. Rumors swirled that he was unfit for command, and the press published newspapers calling Sherman “mad” and “insane.” In October of that year, he was relieved of command and spent several months at home recovering. Grant stood by Sherman during that time and welcomed him back to command in December 1861.

Shiloh, and the leadership Sherman showed during that time, proved that he had regained his mental state. By late 1863, newspapers no longer saw him as a liability; in fact, following successful engagements at Shiloh, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga, Sherman was seen as a rising star in the Union Army. His understanding of warfare was about to be put to the test as the war entered into its final years.

The Atlanta Campaign

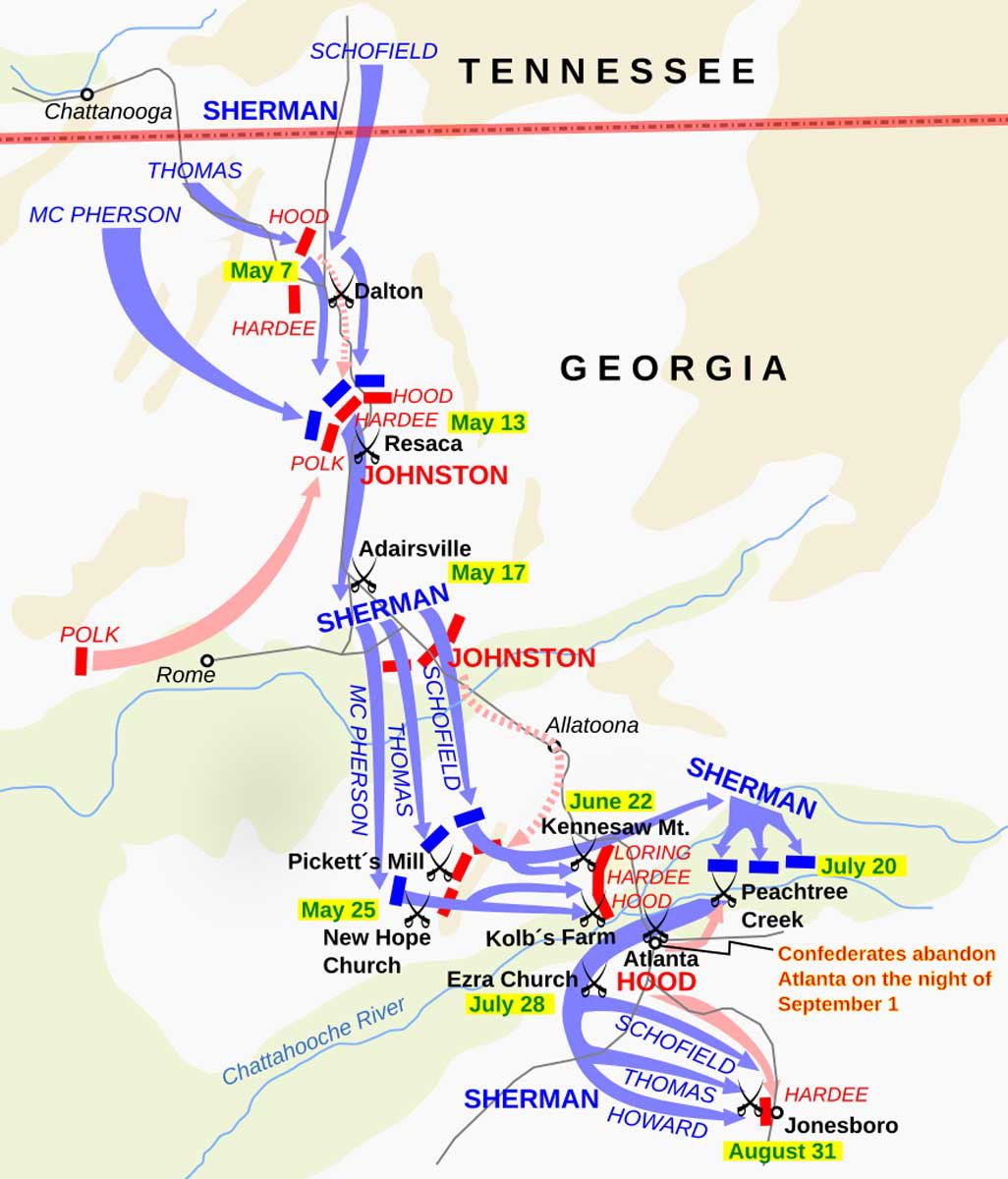

In 1864, Sherman was given command of Union forces in the West as Grant was reassigned to the East to take on Robert E. Lee. Sherman launched the Atlanta Campaign—a months-long effort to take one of the Confederacy’s last major metropolitan cities and a hub for commerce.

Capturing the city would devastate Southern morale and drastically diminish their capability to continue the war effort. Sherman faced off against Confederate generals like Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood, pushing his troops through tough terrain and constant resistance as he made his way south from Tennessee into the heart of Georgia. While difficult, Sherman was able to consistently force the Confederates south towards the capital.

In September, Sherman finally took Atlanta. The victory was more than just a military win—it came at a critical time politically. President Abraham Lincoln was up for re-election and facing growing criticism over the war’s progress. Sherman’s capture of Atlanta helped turn public opinion in Lincoln’s favor and boosted Northern morale, leading to his reelection.

The March to the Sea

After taking Atlanta, Sherman launched what would become his most famous, and controversial, campaign: the March to the Sea. In November 1864, he led 60,000 troops from Atlanta southeast to Savannah. Atlanta had not been enough to demoralize the South. The March to the Sea would showcase for the first time what Sherman called “scorched earth tactics,” more commonly known today as “total war.” His troops burned crops, bent rail lines, which famously became known as “Sherman’s neckties,” and raided supplies from local populations along the way. Sherman believed that by bringing the war directly to Southern civilians, he could force the Confederacy to surrender faster. The strategy worked. His army reached Savannah in December, facing little resistance. The city was spared destruction as Sherman believed it was too beautiful to burn, and Sherman offered it as a “Christmas gift” to President Lincoln.

The March to the Sea was effective, but it impacted the way military operations would be waged in the future. Sherman showed that to successfully wage a war, you must bring its devastation to everyone involved.

South Carolina Campaign

Following his success in Georgia, Sherman turned his attention north. In early 1865, he marched his army through the Carolinas, aiming to link up with Grant’s forces in Virginia for a final push on Lee’s forces. The campaign was brutal. Sherman’s troops faced harsh weather and difficult terrain, but they pressed forward, capturing key cities like Columbia and Fayetteville. In Columbia, fires broke out, Sherman denied that he ordered the burning, but the event added to his already growing controversial legacy.

As he advanced, Confederate resistance crumbled. By April, General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to Sherman in North Carolina, just days after Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. Sherman’s campaign through the Carolinas helped seal the Confederacy’s fate. It also showed his commitment to this new tactic of total war. Though often overshadowed by the surrender at Appomattox, Sherman’s work in the final months of the war was crucial.

Reconstruction Era

After the war, Sherman stayed in the Army and took on several key roles during Reconstruction. He served as commander of the Military Division of the Mississippi, overseeing large portions of the South as it was being rebuilt. Sherman shared Lincoln’s view of restoring order and the old Union quickly, but had little patience for politicians. He often clashed with Radical Republicans in Congress who wanted more aggressive policies that would punish the South for secession and give sweeping rights to newly emancipated slaves.

While Sherman was firm in his belief that the Union had to be preserved at all costs, he didn’t always agree with the vision of what the postwar South should look like, as many at the time had differing viewpoints on the methods and goals of reconstructing the country. Many urged Sherman to run for President, and while he helped enforce federal law, it was clear he was more comfortable on the battlefield than in the halls of government, as he often said, if he were elected, he would never serve.

Legacy

William Tecumseh Sherman remains one of the most talked-about figures of the Civil War. His tactics helped bring the conflict to a close, and his partnership with Grant was one of the most effective in US military history. His “total war” strategy—especially during the March to the Sea—has been used to demonstrate effective scorched earth tactics in today’s military institutions.

After retiring from the Army, he remained outspoken and continued to write about his experiences, eventually publishing his memoirs. He famously turned down several offers to run for political office, once saying, “I will not accept if nominated and will not serve if elected.” Sherman died in 1891, but his influence lives on. Whether viewed as a ruthless warrior or a brilliant strategist, he left a mark on American history that won’t be forgotten.