Before the era of Classical Greece, when hoplites fought shield to shield, and Athenians pondered the benefits of democracy, there was another Greece. One that ended almost a millennium before the rise of Athens as a powerhouse of the ancient world. This was the age of Mycenae, and it provided the foundation for the Greek myth and legends, from Achilles and Ares to Hector, Hera, and Hercules.

Unlike the myths, however, Mycenae was real. And the artifacts it provided showed a place full of mystery that has intrigued archaeologists and explorers ever since. Of special note were the eerie gold masks and the awe-inspiring Lion Gate, tangible and mysterious symbols of wealth and power that reflect Mycenae’s special status in the annals of Greek history (and prehistory!).

Mycenae: A Powerful Fortress

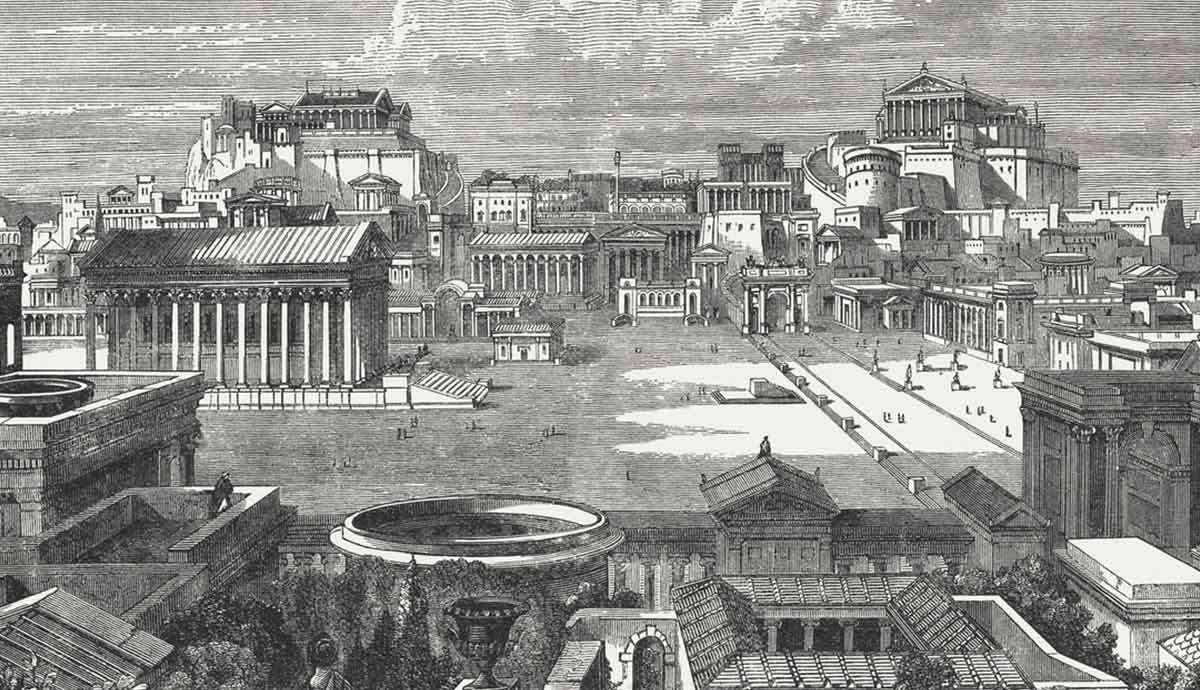

Located 120 kilometres (75 miles) south-west of Athens in the Peloponnese region, Mycenae was a major center of Greek civilization in the Late Bronze Age, and because of its importance, the era from 1600 BCE to around 1100 BCE in Greece is described as “Mycenaean.”

Homer wrote of Mycenae as “broad-streeted” and “golden,” and the seat of power of Agamemnon, the commander-in-chief who led the Greek forces in their battle with Troy. By the time the Greeks of classical antiquity were around, Mycenae was already ancient, and a site infused with legend and myth. Built atop a hill overlooking the surrounding landscape, Mycenae had a dramatic setting, and the masonry blocks are so large that later Greeks supposed the citadel was built by Cyclopean giants!

The exact reason for Mycenae’s end is not known, although, like other settlements and civilizations at the end of the second millennium BCE, it was likely due to the effects of the Bronze Age Collapse. Internal strife, war, and natural disasters could all have been the culprits. The site went through periods of inhabitation and abandonment afterwards, eventually becoming a tourist attraction during the Roman era.

Excavating the site in the 19th century was a huge task, and at the center of much of the archaeological work was the self-taught, and contentious archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, who brought his discoveries to the attention of the world and drew harsh criticism for his methods and his wild claims.

Unearthing Mycenae

When excavations began in 1874 on Mycenae by the controversial Heinrich Schliemann, it was the moment that myth and history collided. Driven by his belief that myths led to hidden cities and that there were real-life foundations for Greek fables of antiquity, Schliemann blasted (literally) his way to finding the answers that he wanted to find.

Despite his unorthodox and destructive methods, he did, in fact, find things that generated intense debate and changed the way we view the ancient world. His grandiose statements and sensationalized publicity brought major attention from the public eye, and his exploits were followed with great interest.

“Grave Circle A” was the first of Schliemann’s excavations at Mycenae, and it heralded important discoveries that confirmed Schliemann’s belief that the site was linked to Homer’s Iliad. The 16th-century BCE royal cemetery contained six shaft graves containing a total of 19 bodies. Generating huge interest was the discovery in two of these graves of a total of five golden death masks. One of these masks, Schliemann believed, was the death mask of King Agamemnon, whose remains he believed he had found.

The Mystery of the Golden Masks

Subsequent analysis revealed “The Mask of Agamemnon” was made around 1500 BCE, several hundred years before Agamemnon, as mentioned in Homer’s writings, was thought to have existed. There are some suggestions that the mask may even be older, completely debunking all possibility of Schliemann’s claim. However, while the Iliad is considered poetic and not an actual historical source, there are many who believe it to be based on true events. The remains of what is likely Troy come from the site of Hisarlik in Turkey, which show a massive fortified city that was destroyed in 1180 BCE.

The mask was made from a thin sheet of gold, hammered against a wooden background, and it likely represents the person whose face it rested upon. Who exactly this person was is unknown, but he would have been of extremely high status—quite likely a king. When Schliemann notified King George of Greece about the discovery of the mask, he famously declared, “I have gazed upon the face of Agamemnon.” His dramatic claim has drawn criticism, not just for its overzealous and premature nature, but even by the object it referred to.

The mask differs significantly in its design from the other masks that were found at the site. It has a pointed beard and a style of mustache that does not align with other Mycenaean imagery of the era’s fashion. It is also unique in comparison with the other masks in that it has far more attention to detail, including cut out ears, and a three-dimensional appearance. Given Schliemann’s reputation, these factors have led some to believe that the mask is actually a forgery. David A. Traill posits in his book, Schliemann of Troy: Treasury and Deceit, that the mask could also be genuine, but altered by Schliemann.

With Schliemann’s controversial antics aside, there is no doubting that the masks, including that of “Agamemnon,” raise more questions than they answer, many about their purpose, the rituals that went with them, and the Mycenaean beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife. In this field, imagination and supposition are still large factors attached to established fact.

The Lion Gate: A Symbol of Power

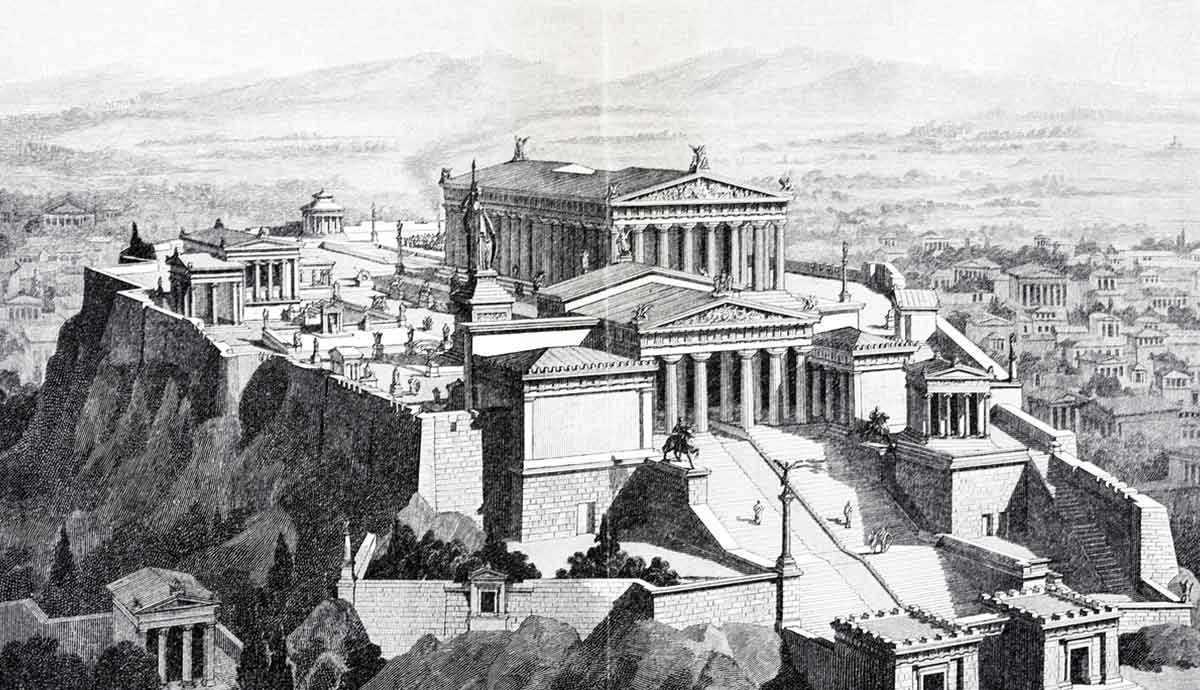

At the northwestern side of the Mycenae acropolis is the entrance to the citadel. The “Lion Gate,” as it is known in modern terminology, is so called for the sculptured likeness of two lionesses that sit in a relieving triangle atop the entrance’s lintel. Built from massive stone blocks, the gate sits at the end of a long, defensible defile, effectively creating a sense of vulnerability for those approaching the grandiose fortress.

The gate is a wonder of engineering and contains many interesting facets in its construction. The entrance is fairly large, being 11.5 feet high and 10 feet wide (reduced to 9 feet just below the lintel), and is flanked by huge stone blocks that would have taken considerable effort to move into place. Above the entrance, the construction uses a corbelled arch technique to lighten the load on the lintel and the supporting posts.

The Lion Gate was a powerful and permanent feature that commanded admiration and awe. A testament to this fact is that the gate has stood in place, virtually undamaged, since it was built in 1250 BCE. The relief of the lionesses also represents the oldest monumental sculpture in Europe, and must have been even more awe-inspiring at the time of the Mycenaeans, as there was probably little else to which such a structure could be compared.

It is difficult to tell for certain what abstractions the lion relief represented, but it is a reasonable assumption to state that lions, as they have in virtually every other culture around the world, were symbols representative of strength, power, protection, ferocity, and authority. At Mycenae, they were the first thing that visitors saw as they entered the fortress, conveying a sense of regal might and reminding the visitor of the power that surrounded them. During the Mycenaean Era, lions were common throughout Greece. And their range extended westwards across the Mediterranean region. Herodotus even noted lions lived as far north as the Balkans.

The Relics as Representations of Mycenae

Perhaps the best-known relics of Mycenae, the golden masks and the Lion Gate, while very different objects, are evocative of many things, and provide great insights into the culture. The masks are indicative of wealth, while the gate represents an engineering marvel for the time period. Together, they are symbols of regal authority, power, and an intricate knowledge of craftsmanship far ahead of many of their contemporaries, from gold filigree to the moving of massive stones.

Not only are they relevant to Mycenae itself, but they also reflect the words of Homer, who spoke of Mycenae as a rich and powerful kingdom. The real-world evidence suggests Homer’s words were not just fantastical myths. Instead, they had a basis in actual history. This stunning revelation was a sensation when Mycenae was excavated, and it continues to fuel interest to this day, as the mysteries of the Mycenaeans and their great fortress are slowly revealed.