Marseille prides itself on the name la cité phocéenne, the Phocaean City. The nickname of France’s second city comes from Phokaia, a Greek city over 2,000 kilometers away in Ionia (modern Turkey). It is the story of Greek colonization that connects these two ends of the Mediterranean. Marseille, or Massilia as it was known to its founders, began as a small outpost in the far west around 600 BCE and evolved into one of the most significant Greek cities west of Sicily. Famous for its medicine, wine, and explorers, Massalia played a significant role in shaping the history of the western Mediterranean.

The Age of Greek Colonization

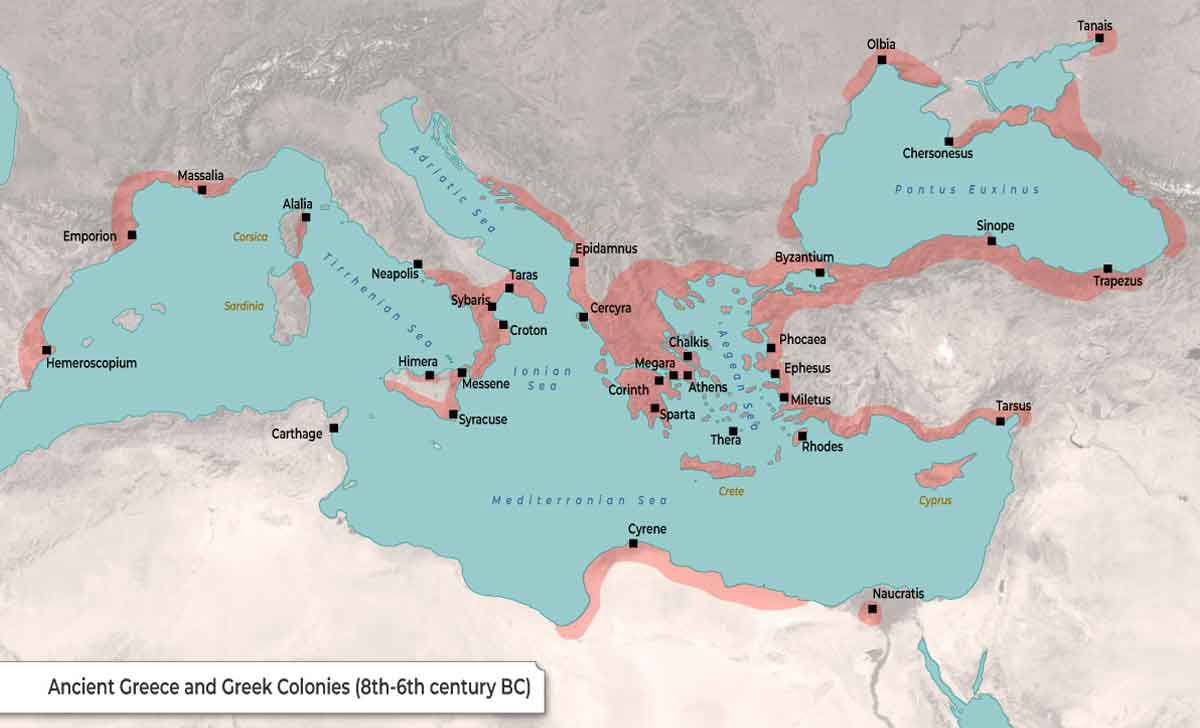

The inhabitants of the Greek city-states, poleis, of the 8th to the 5th centuries BCE were seafarers who sailed across the Mediterranean and Black Seas. Instead of returning home, many established roots, founding Greek cities from the Crimea to Spain. The southern shores of the Black Sea, the eastern Aegean, and southern Italy and Sicily all hosted substantial Greek communities, which in many cases existed well into the 20th century CE and continue to have a legacy today.

There was no single model or motivation for the founding of a Greek colony. Generally, the colony was a small outpost, near or directly on the coast. A polis typically consisted of an urban center and a surrounding territory (chora). The same was often true of colonies, though few colonies controlled a large area of land. Relations with the indigenous populations ranged from cooperation and cohabitation to conflict and segregation.

Massalia may have been an example of a small, unobtrusive presence that introduced new ideas, products, and technologies, and was welcomed or at least tolerated. This was in contrast to more aggressive colonies, which conquered valuable land and marginalized or enslaved the local inhabitants, a model seen in parts of Sicily. Equally, some Greek colonies were established on the fringes of powerful communities and had to be, to some extent, subject to them, as in Egypt.

Generally, colonies were sent out by a polis, with Phokaia, Miletus, Chalkis, and Eretria leading the way. Phokaia, while not a major state in later Greek history, was important in archaic Ionia. With excellent harbors on the eastern Aegean coast, the Phokaians were said to be amongst the first Greeks to undertake long voyages and were more accustomed to the sea than the land (Herodotus 1.163). When Phokaia was threatened by the Persians in the 6th century BCE, the population took to their ships and set sail for the western Mediterranean.

Several motivations acted as push and pull factors. Trading links between Greece and the eastern and western Mediterranean dated back to the Mycenaean era in some cases (Graham, 2006, p. 95). The Phokaians were widely regarded as energetic traders. There were also conditions pushing people away from Greece. Archaeological evidence suggests that the population in Greece was increasing as colonization began in the 8th century BCE (Graham, 2006, p. 157). A growing population may have encouraged the search for land and prompted political unrest. A surplus population or losing faction in a civil war may well have been sent out to seek their fortune elsewhere.

Foundation Myths

Several versions of Massalia’s foundation story were recorded by later writers. When a polis sent out a colony, it often followed a specific pattern. There would be a consultation of the gods, and often a visit to the oracle at Delphi. Oaths were sworn, and a local noble was appointed as the leader and founder of the colony. When these stories were written down a century or more after the event, they had evolved into a semi-mythologized set of standard tales.

One of the most widely circulated stories places the origins of Massalia at a wedding. The wedding story exists in two slightly different versions transmitted by the much later writers Justin in the 2nd century CE (43.3) and Athaenaeus in the 4th century CE (13.36). In this story, the Phokaians arrive at the mouth of the river Rhône and get invited to the wedding of the local king Nannus, or Nanos. It is up to the daughter of the king, Gyptis or Petta, to choose her husband by handing them a bowl at a feast. She unexpectedly chooses Protis (or Euxenus), a Phokaian invited to the feast. The king honors his daughter’s choice and allows the Phokaians to build a city that becomes Massalia.

As the confusion with the names implies, it is doubtful this is an accurate record of events. However, it could be a dramatized retelling of a vital element in the foundation of Massalia. It is clear from the stories that the Phokaians did not sail randomly to the Rhône. They had a knowledge of the region and perhaps an existing relationship with the local people. Since Greek colonization expeditions were mainly male affairs (Graham, 2006, p. 147), there would have been a need for intermarriage. Perhaps the story reflects that the initial foundation of Massalia was a negotiated affair that grew out of beneficial relations between the two groups.

Interestingly, another story gives a prominent role to a woman. Strabo (4.1.4) says that before setting out, the Phokaians, in response to an oracle, sailed to Ephesus in search of a guide. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus was important to all the Ionian Greeks. In Ephesus, a prominent woman named Aristarcha had a dream in which the goddess commanded her to embark on a journey and retrieve sacred objects from the temple. Aristarcha sailed with the expedition and, once in Massalia, became a priestess. From that point on, the Massaliots maintained a cult of Artemis, which linked them to their homeland.

Colonies and mother cities often maintained a strong connection, often expressed through shared religious practices. While Strabo’s story appears to conflate the foundation of Massalia with the evacuation of Phokaia, which likely occurred several decades later, it still conveys information about colonization.

Archaeological Evidence

The stories of Massalia’s foundation can be enhanced by archaeology and our understanding of Greek colonization.

Archaeological investigations in and around Marseilles suggest the city was founded around 600 BCE (Hansen & Nielsen, 2004, p. 159). As the stories of the wedding of Protis imply, the Phokaians had prior knowledge of the area. Greeks had already arrived in Italy and Sicily in the 8th century, bringing them into contact with the Carthaginians, Etruscans, and nascent Romans. The Etruscans had well-developed contacts with southern Gaul and the Ligurians (Lucas, 2019, p. 69).

Given the Phokaians’ experience as traders, we can imagine they would have explored the commercial opportunities offered by the western Mediterranean trade routes. One of the many commodities coming from northern and western Europe at the time was tin, a key component in the creation of bronze. Massalia was one of several Phokaian colonies established in southern France, Corsica, and Spain that would have access to the tin routes. Phokaian colonies largely did not attempt to control a large hinterland, suggesting that their primary interest was trade rather than land (Graham, 2006, p. 140).

The future site of Massalia had obvious appeal. Massalia was built on a series of hills overlooking one of the best natural harbors in the region, the modern Vieux Port. The hills and nearby marshes made it easy to defend, while the port gave sheltered access to the sea. To the east lay Italy and Etruscan trade. Just to the west lay the mouth of the river Rhône, giving access to the goods of northern Europe.

The marriage of Protis implies a cooperative relationship with the inhabitants of southern Gaul. The Massaliots certainly had something to offer: wine. Strabo (4.1.5) describes the region as good for vines and olives but poor for wheat. The wine introduced by the Massaliots quickly gained popularity, and its consumption transformed the local Celtic societies. Wine drinking and the paraphernalia of its consumption at feasts became a part, and perhaps a maker of, elite Celtic life, while Massalia came to dominate the commercial life of the region.

The fact that one of the first things the new inhabitants did was to build a wall suggests that the goodwill of the locals could not be completely relied upon. Before telling the story of Protis’ marriage, Justin informs us that the Massaliots had to combat the fierce local tribes. Justin (43.4) also provides an interesting story regarding the second generation. After the initial peaceful contact, the successor of Nonnus plotted to attack Massalia alongside the neighboring Ligurians. The plot only failed when a local woman in love with a Greek warned the Massaliots, who, ever after, kept a close watch on foreigners.

Massalia certainly had other enemies. There are several references to battles between Massalia and Carthage, at least some of which the Massaliots claim to have won. It is possible that Massalia played some role in the story of the Phokaian refugees who fled the Persian attack in c. 545 BCE. Strabo appears to have conflated the story of Aristarcha with this event, which resulted in a Phokaian colony on Corsica being driven out by the Carthaginians and Etruscans.

A Civilizing Influence?

While it had its enemies, Massalia survived and thrived. Behind its walls, the city soon had the features of any other Greek town. Temples of Ephesian Artemis and Delphian Apollo graced the hills above the port, though their remains have not been found. Archaeologists frequently come across the remains of Massalia during work in the city center, where a marketplace (agora) and naval works have been located around the Vieux Port. At its height, Massalia likely had a substantial population of around 20,000.

Like every polis, Massalia had its own government, which, according to Strabo, consisted of a narrow aristocracy comprising a council of 600 and a small executive committee. To be a councilor, your family had to have been citizens for at least three generations. Given that we are also told there were families in Massalia who claimed descent from the founder Protis three hundred years later (Athenaeus, fr. 549), we are left with the impression of a conservative society that closely guarded its lineage and identity.

Following its foundation, Massalia became one of the major cities of the classical Mediterranean. Along with introducing wine to Celtic society, Massalia helped disseminate other Greek elements, such as the alphabet and silver coinage (Bouffier, 2009). The prejudice of our Greek and Roman sources led them to portray Massalia as a kind of beacon of civilization, teaching the barbarian inhabitants of southern Gaul the arts of civilized life, such as walls, vines, and laws.

Scholars today give the inhabitants of Gaul much more agency in their relationship with Massalia. The Massaliots became commercially and militarily powerful in southern Gaul, founding several colonies, including Agathe (Agde) and Nikaia (Nice). These settlements initially started as fortresses and eventually developed into major towns. However, Greek did not become dominant as it did in southern Italy and Sicily, although the local elite were adept at selecting and adapting the elements of Greek culture that suited them (Lucas, 2019, p. 73).

The Massaliots maintained the seafaring traditions of their Phokaian forebears and produced some of ancient Greece’s great explorers. Perhaps the most famous Massaliot was Pytheas, who was said to have explored northern Europe in the 4th century BCE. Pytheas claimed to have reached the British Isles and the mysterious Thule, which has been variously placed anywhere from the Orkneys to Iceland.

Roman Massalia

Like many Greek cities, Massalia’s later history was entangled with that of Rome. There are traditions that date the friendship between the two to the early phases of Phokaian colonization. One story records that the Massaliots aided Rome after the city was sacked by the Gauls in 390 BCE (Justin 43.5). Rome’s defeat of Carthage in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE repaid the favor by removing one of Massalia’s principal trading rivals and increasing the city’s commercial dominance (Bouffier, 2009). Once the Romans crossed the Alps into southern Gaul in the 2nd century BCE, they were again of service to Massalia as they protected the city from attack. While a Roman province grew around the city, Massalia continued to govern itself. Massalia benefited in several ways from the rise of the Romans, but gradually the new power marginalized the old city. Commercial activity was taken over by the Romans, and the center of gravity in southern Gaul shifted to Roman sites such as Narbonne (Bouffier, 2009).

By the time the Massaliots chose the wrong side in the Roman civil war and were besieged by Julius Caesar in 49 BCE, the city was already said to have been in decline. However, Massalia retained a high reputation among the Romans and was well regarded for its schools of medicine and philosophy, as well as its supposed civilizing influence. So highly regarded was this city founded by Phokaians that Strabo (4.1.5) tells us that 1st-century BCE Romans often preferred Massalia to Athens.

Select Bibliography

Bouffier, S. (2009) “Marseille et la Gaule méditerranéenne avant la conquête romaine,” Pallas, 80: 35-60.

Graham, A.J. (2006) “The colonial expansion of Greece” in Boardman, J. and Hammand, N.G.L. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 3 Part 3: The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C. 83-162, Cambridge University Press.

Hansen, M.H. and Nielsen, T.H. (2004) An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis, Oxford University Press.

Lucas, J. (2019). “Marseilles: Greek settlement on the fringes of Iron Age Provence” in Lucas, J., Murray, C.A., and Owen, S. Greek Colonization in Local Contexts: Case Studies in Colonial Interactions, 59-76, Oxbow Books.

Tréziny, H. (2005) “Les colonies grecques de méditerranée occidentale,” Histoire urbane, 13: 51-66.