Japanese Buddhist temples serve numerous functions, from giving shape to the ideas of Buddhist faith, to differentiating the belief system from Shinto, thus giving it its own, unique identity. Moreover, Japanese temples are simply beautiful in a majestic and often ornate way, dazzling visitors with deep colors, glistening metal, and unbelievably grand structures, though that ultimately depends on their style. The best way to understand the splendor of Japanese Buddhist temples is to go visit them in person. Hopefully, though, this guide can be a close second.

Fundamental Differences Between Shinto Shrines and Buddhist Temples

Japan’s current religious landscape has been shaped by the centuries-long coexistence of Shinto, the indigenous animistic belief with roots possibly dating to prehistory, and Buddhism, introduced from India via China and Korea in the mid-6th century. The distinction between Shinto shrines (jinja, miya, yashiro, jingu) and Buddhist temples (tera, otera) is not merely religious but also architectural and philosophical.

Oral tradition says that Shinto shrines first appeared in Japan in the 1st century BCE. But in those times, a “shrine” did not necessarily mean an artificial structure. Anywhere where a kami divine spirit dwelled and could hear the pleas of their believers could be a “shrine”: a field, a river, a mountain. Proper shrines as we think of them today probably first appeared around the 5th or 6th century CE. Originally, they were temporary constructs meant for specific rituals, often erected in the heart of nature. Once a rite was done, the shrine would be disassembled.

Over time, these sacred structures evolved into more permanent buildings but they never forgot their roots, eschewing metal fittings or painted wood to show reverence to nature, and being dismantled every 20 years to be reborn from new materials on shrine grounds. Not all shrines continue this (needless to say very expensive) tradition, but many do. Japan’s Shinto shrines are further easily identified by their iconic torii gates, often painted in red to ward off evil spirits.

Japan’s Buddhist temples, on the other hand, are expansive, architecturally elaborate, and doctrinally oriented inwards towards the individual and their quest for enlightenment. Yet at the same time, they also exist to remind people of the cosmological Buddhist order. While the same can be said about some Shinto shrines, Japanese Buddhist temples are more often multi-building complexes with tight security, be it in the form of protective walls or fierce guardian statues standing inside grand gates.

Temple roofs tend to be tiled and more elaborate, showing influences from mainland Asia. From above, tiled temple roofs resemble rows of ceramic pipes carefully harmonized with the whitened eaves to create a visual illusion of the roof gently floating in midair. Ornamentation in the form of metal fittings, gilding, wood adorned in various colors, and the presence of statues are other characteristics of Japanese Buddhist temples.

Buildings of the Buddha

Buddhist temple architecture in Japan is organized around a group of buildings with specific functions making up a single complex. One of the most classic temple styles is the shichido-garan or “seven-hall complex,” though it is not universal and its implementation differs depending on the specific school. Those temples that liked to keep things traditional were made up of a sammon main gate, a butsuden or kondo main hall housing sacred relics, the hatto lecture hall where studies were conducted, the sodo hall where monks lived and meditated in groups, the yokudo ablution hall, the kuri kitchen, and the kawaya latrines.

Other structures that you could also find at some of the bigger temple complexes are the jikido dining hall, the shoro belltower, the kyozo sutra repository, and of course the pagoda. Derived from the Indian stupa and transformed by Chinese and Korean architectural influences, a Japanese Buddhist pagoda can have three, five, nine, or 13 tiers, is made of wood, and typically houses relics and ashes of departed devotees. For example, Horyu-ji, Japan’s oldest temple, is home to a famous five-story wooden pagoda.

However, the specific layout of these structures, and even the total number of structures in a complex, differed greatly depending on the importance of the temple. For example, by the 11th century, the Enryaku-ji temple on Mt. Hiei in the old capital of Kyoto, was made up of over 3,000 buildings. Today, about 150 remain, spread across 1,700 hectares.

Architectural Styles of Buddhist Temples: A Cosmos of Differences

Wayo Style

Originating in the Heian Period (794–1185), the Wayo style is characterized by simplicity, minimal ornamentation, and a close relationship with nature, possibly taking inspiration from Shinto shrines in order to better integrate Buddhism into the Japanese religious landscape during its early years in Japan. The Wayo style features thin columns, low ceilings, and minimally adorned wood, all arranged in a way to create an open space divided with screens, which could be removed to integrate a temple with the natural environment. It is thanks to this style that Japanese Buddhist temples developed a tradition of maintaining beautiful, lush gardens.

Daibutsuyo Style

Introduced during the Kamakura Period (1185–1333), the Daibutsuyo style was heavily influenced by the temple designs of Song Dynasty China. Unlike the subdued Wayo style, this temple architecture emphasizes grandiosity in everything from the size of the buildings to the massive exposed beams or sacred statues. The Todai-ji’s Great Buddha Hall (Daibutsuden) with its 15-meter-high Great Buddha statue is a quintessential Daibutsuyo monument.

Zenshuyo Style

Also appearing in the Kamakura Period, the Zenshuyo style is closely associated with Zen Buddhism and is characterized by austerity, minimalism, and earthen floors. The interiors are dim and subdued in order to create a space conducive to introspection and meditation.

Setchuyo Style

During the Muromachi Period (1336–1573), Japanese architects began to synthesize earlier styles into a hybrid known as Setchuyo. This approach combines elements of Wayo, Daibutsuyo, and Zenshuyo into a clearly distinct amalgamation of simplicity and grandeur. Temples in the Setchuyo style are often built in tiers with restraint and minimalism stacked upon a parade of daring colors or vice versa as seen in the famous Kinkaku-ji (Golden Pavilion) in Kyoto. The Setchuyo style can also be expressed via a heavily ornate temple in the middle of a natural setting, creating a mesmerizing contrast of two worlds.

Case Study: Todai-ji and the Great Buddha Hall

The Todai-ji temple in Nara stands as one of the most enduring symbols of Japanese Buddhism. Founded in the 8th century by Emperor Shomu, it was intended to promote Buddhist unity across the country. At the heart of this temple complex is the Daibutsuden, or Great Buddha Hall, which houses the colossal bronze statue of Vairocana Buddha. The original hall was burned down in 1180 and then again in 1567, and the one standing today dates back to the Edo Period (1603–1868), but it stands mightily. Todai-ji’s Great Buddha Hall is the largest wooden structure in the world, measuring over 57 meters in width and 48 meters in height.

Despite being smaller than the original structure, the Great Buddha Hall remains as majestic and awe-inspiring as it was over a thousand years ago. The wooden structure is a celebration of life through the use of natural materials, while the statue of the Buddha represents a world beyond our own and the enlightenment that is the ultimate goal of any Buddhist. Adjacent to the Great Buddha Hall is the Shoso-in Repository treasure house. Its raised floor, stacked timber walls, and stone foundation are not only uniquely Japanese Buddhist architectural concepts, they also protect priceless artifacts from moisture and pests.

Warrior Temples

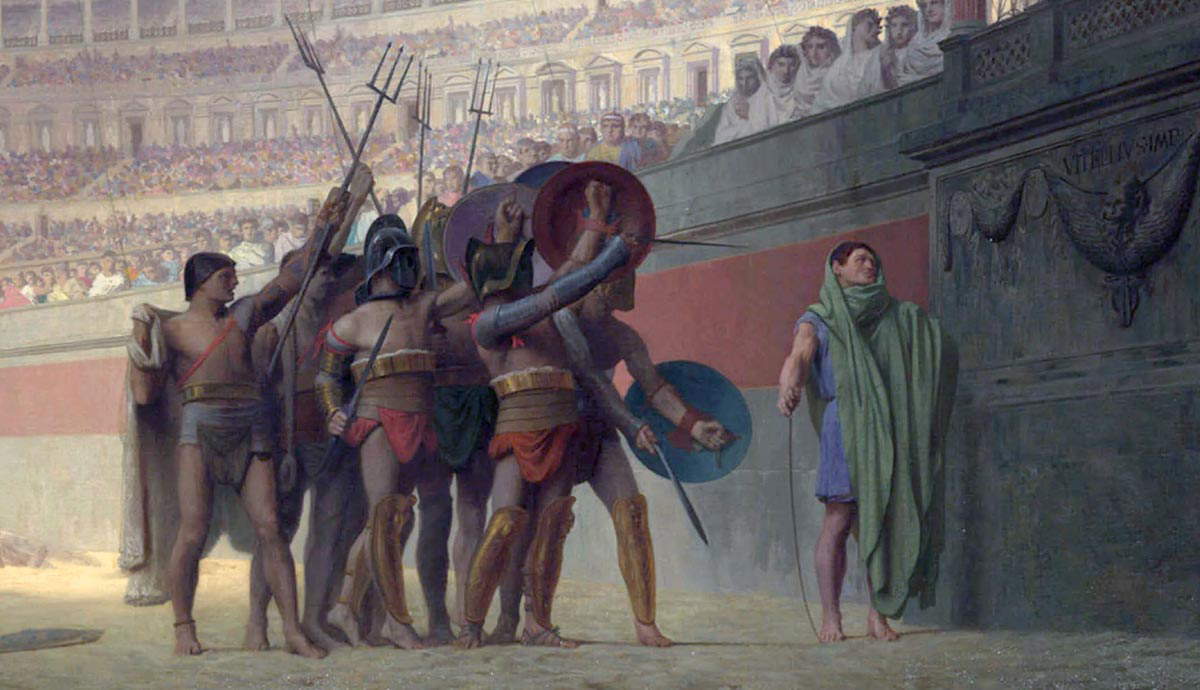

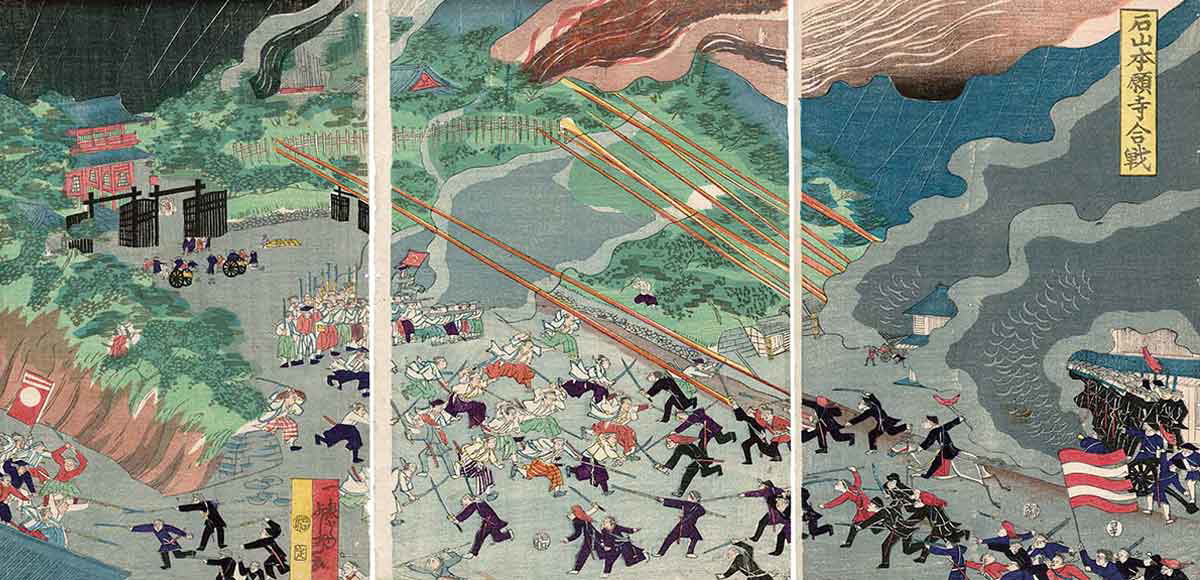

Japan has a long tradition of warrior monks going back to the 10th century, but despite this, the introduction of a soldier class to monastic life did not fundamentally change the architecture of Buddhist temples. The biggest ones like Todai-ji or Enryaku-ji were capable of creating embankments, digging ditches, and building palisades, but they primarily relied on their status and natural terrain to protect them. It was the Ikko-Ikki—leagues of Buddhist peasant zealots led by monks—who constructed actual fortified temples.

These complexes, like Ishiyama Hongan-ji, were usually clearly divided into sacred and secular areas, since monastic warriors were not always strictly speaking monks and required plenty of laymen to serve as support staff. This turned Ikko bases into two separate worlds.

The sacred parts of those temples were the most beautiful and the most fortified, with gates, stone terraces, fences, palisades, moats, and ditches protecting the main hall, the lecture hall, or the sutra repository. By contrast, the secular side, while still protected, usually only offered one layer of fortifications between the outside world and living quarters, kitchens, and refectories.

This process was similar to how towns developed around Japanese castles, and by the 16th century, a fortified Ikko temple and a fortress of a warlord were virtually indistinguishable from each other, adding to the fascinating architectural heritage of Japanese Buddhist temples.

Sources:

Turnbull, S. (2008), Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949–1603.