When it comes to colonial Colombia, two places dominate and receive by far the most visitors. Cartagena rightly hogs the spotlight, being one of the largest and grandest examples of Spanish colonial architecture in Latin America. La Candalaria, the old town of the country’s capital—Bogotá—is also well-known thanks to its accessibility and well-preserved streets. Beyond the tourist trail, however, is a wealth of spectacular historic settlements that more than justify the effort of straying off the beaten path.

1. Villa de Leyva

Just a few hours from Bogotá, and nestled in an open valley, Villa de Leyva is one of Colombia’s most well-preserved colonial towns. Its cobbles are charmingly uneven, its storied buildings are painted a blinding white, its roofs are made from fading terracotta. It was home to revolutionary figures as well as ancient peoples who built mysterious monuments. Surrounded by a surprising diversity of spectacular natural landscapes, everything from dusty semi-desert to misty páramo can be found nearby.

This was a significant place long before the Spanish arrived. Nearby are several well-preserved fossils of enormous marine animals that co-existed with the dinosaurs, proof that the area was once under water despite the town’s altitude. Little is known about this region’s early human history, but whoever occupied the valley two thousand years ago must have considered it important. Twenty minutes from Villa de Leyva is a site that the Spanish named “El Infiernito”—Little Hell. The stone columns that make up the site are arranged to align with the movements of the sun, leading some to believe that it was used as some sort of calendar.

Around the ninth century CE, the indigenous Muisca confederacy emerged, and this loose collection of chiefdoms controlled the high plateau from here to the south of Bogotá. The Muisca considered lakes to be sacred places, and it is with them that the El Dorado myth has its origins. While conquistadors believed it to be a lost city of gold, El Dorado actually referred to a Muisca leader. This chief would be painted in gold dust before diving into Lake Guatavita between Bogotá and Villa de Leyva. Iguaque Lagoon, high up in the mountains behind Villa de Leyva was also very important, being the place from which the ancestors of humanity were believed to have emerged.

The Muisca chose not to settle here permanently, as their culture was semi-nomadic and the dry land was unsuitable for cultivation. The Spanish had no such issues, founding Villa de Leyva in 1572, and handing out land to ex-soldiers as a reward for their service. The military connection explains why the town has the biggest square in Colombia—a place was needed to practice maneuvers should the soldiers ever be needed again. Alongside the veterans, Villa de Leyva quickly attracted the Catholic Church, and its priests left their mark on the town. Behind a set of unassuming walls, the Claustro de San Francisco is a little oasis of tranquility and greenery. A statue of Jesus stands on the hill behind the town, providing spectacular views for those who climb up to visit.

Villa de Leyva’s most famous inhabitant was Antonio Ricaurte, for whom the wider province is named. Ricaurte was born in the town, and after a career in colonial administration he joined the rebellion against Spanish rule. Fighting alongside Simón Bolívar, he died helping to liberate Venezuela. His family home has been turned into a museum, as has the house of another famous resident—Luis Alberto Acuña. While Fernando Botero may be Colombia’s most famous artist, Acuña is well known within Colombia for his distinctive psychedelic style. A collection of his eye-catching works can be viewed at the Museo Luis Alberto Acuña on the main square.

2. Barichara

Barichara has not one, but two spectacular features that combine to create a town some call the most beautiful in Colombia. Its small historic streets are breathtakingly beautiful, but on top of this, they stop abruptly at one edge of town to give way to a dramatic and deep river valley. Its historic buildings are so well preserved that it is usually cited as the inspiration for Disney’s film Encanto. The town’s name means “Place of Rest” in the indigenous Guane’s language, and this feels like an apt name. It is sleepy and relaxed, providing a refuge from the bustle of Colombia’s better-known destinations. Stone carving is historically a specialty of Barichara’s townspeople, and this is reflected in the cobbles and facades of its quaint houses.

Like Villa de Leyva, Barichara’s history pre-dates humanity. The fossilized shells of creatures that lived millions of years ago demonstrate that it too was once a mecca for marine life. These fossils are so abundant that the curls of shells can be seen pressed into the buildings’ stone walls. Locals sell them to visitors from improvised stalls for just a few dollars. The Guane people, from whose language the town’s name is derived disappeared soon after the conquest, so relatively little is known about them. It is thought that they were linked to the Musica and probably worshiped some of the same deities.

Barichara was founded in 1705, three years after a man claimed to have witnessed an appearance of the Virgin Mary. Although the apparition was never officially recognized, the story was believed by the local population, and a church was built on the spot where it was said to have happened. The new inhabitants who arrived soon afterwards built their homes in the distinctive Andalusian style, as opposed to the grand Castilian fashion seen in other colonial towns. Barichara’s greatest claim to fame came after the end of the colonial period. Colombia’s thirteenth president was born and raised in the town.

Barichara is at one end of the Camino Real—part of the network of Indigenous paths that crossed this region and was adopted by the Spanish authorities to enable local transportation. Today, it is possible to walk a picturesque section of the road from Barichara down into the valley, to the smaller and almost as beautiful village of Guanes. The route weaves through picturesque little farms bounded by dry-stone walling, the original cobbles still forming the path underfoot.

3. Girón

Like Villa de Leyva and Barichara, Girón’s importance waned once Colombia had gained independence, which is why these towns are so well-preserved. Girón was overshadowed by its previously unimportant neighbor Bucaramanga, and today it is a suburb of a much larger city. Its historic streets are no less beautiful, but its busyness gives it a different feel. Many of Girón’s oldest buildings are still lived in, making it a truly authentic Colombian town. Its streets bustle with workers and children on their way to and from school, while its restaurants are squarely aimed at locals rather than tourists.

The old town is intersected by a network of small canals, and some of the quaint little bridges that cross them are hundreds of years old. Windows are protected by intricately carved wooden grates, and the same material has been used to construct the balconies that overlook the streets. Almost every corner offers a new picture-perfect moment in the form of an explosion of bougainvillea overhanging a whitewashed wall, or a church steeple framed by the hills behind.

Girón had a troubled birth, being founded three separate times. In 1631, while on a campaign of conquest, Francisco Mantilla established the town but was quickly ordered to abandon it. A rival settlement, Pamplona, had already claimed the land and argued that he was encroaching on their territory. Mantilla disputed this, but suddenly died in the middle of the court session called to resolve the issue. His cousin moved Girón to a new site 16 miles to the west, but the new settlement was plagued by disease. It was moved once again in 1638 to occupy its present site.

The town also played a role in the end of the colonial era. Colombia’s independence would come in 1819 when Simón Bolívar entered the country from Venezuela and eventually liberated it. The initial declarations of independence took place in 1810 however, when towns across the nation announced their rejection of Spanish rule. Girón was one of these rebellious settlements, and the building within which their declaration of independence was signed has been converted into a museum and restaurant. This is one of the town’s primary attractions, alongside the Parque de los Nieves, and the Basílica Menor del Señor de los Milagros. The wider region is also home to several attractions. Easily visited from Girón is the spectacular Chichimocha Canyon, which reaches a depth of 2,000 meters (6,600 feet) and a length of 141 miles, making it the second largest in the world.

4. Popayán

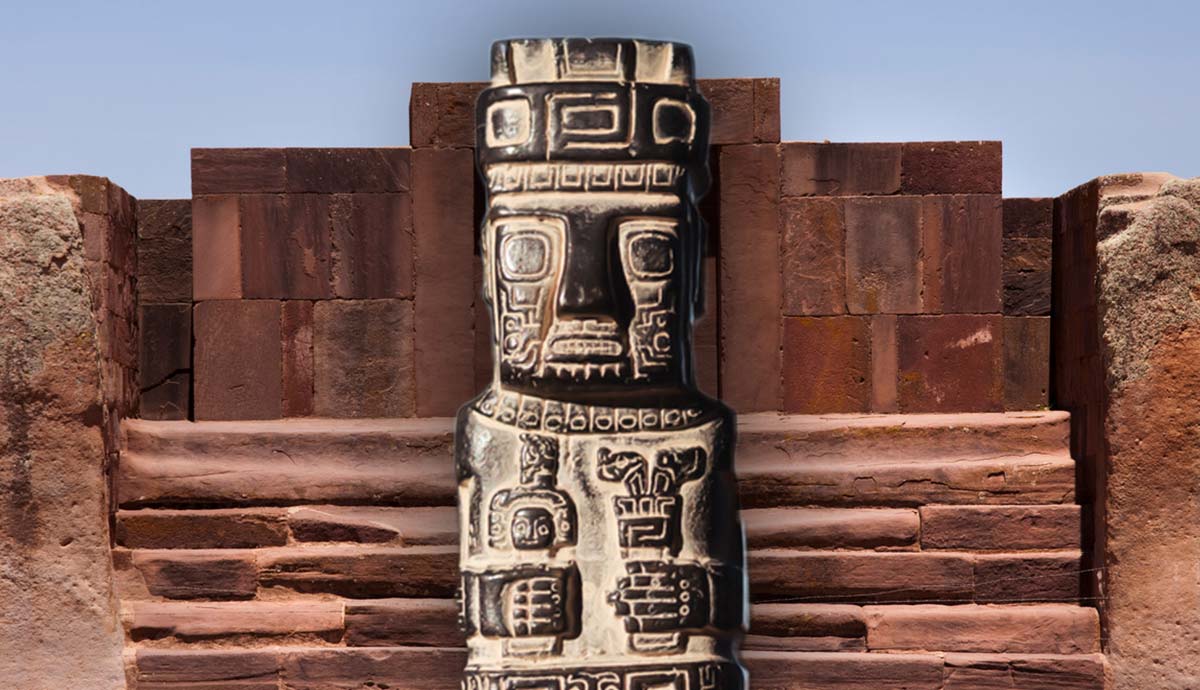

While still only a regional center, Popayán is the most important of the towns listed here. In fact, as one of the oldest cities in Colombia, it has always occupied an important place for the nation’s inhabitants. This part of Colombia has a deep Indigenous history, and Popayán is a necessary stop on the route to the mysterious statues of San Agustín. An unknown indigenous people built a pyramid at the place which would become Popayán—El Morro del Tulcán—and this still sits on the edge of the city’s historic core. Little excavation work has been done, and today it is a steep grassy mound that provides sweeping views of the city. It is still a contested space however, and in 2020 the Misak Indigenous people pulled down a statue of the conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar as an act of protest.

It was Belalcázar who founded the city in 1537, having been placed in charge of Quito by Pizarro during his conquest of the Inca. Belalcázar’s ambitions extended beyond being a minor player in the conquest, and he marched north to claim Colombia for himself, founding Popayán as he did so. Much of the wealth looted from the Inca and extracted from the silver mines in the Andes was shipped to Spain through Cartagena in Colombia’s north. Popayán profited from being an important stop on this route.

Popayán’s importance throughout the colonial period and right up through today means that its historic center is bigger than the other towns on this list, and its architecture is more baroque. It possesses an enormous number of significant buildings, despite periods of destruction caused by earthquakes. Among its most important religious constructions are the churches of San Francisco and Santo Domingo, as well as La Ermita chapel—one of the oldest in Colombia. Today the cathedral is an imposing building, but it began life as a simple straw hut during the earliest days of settlement. Alongside these are various palaces and theaters, as well the buildings that make up the University of Cauca. Founded in 1827, this is among the oldest and most prestigious universities in the country. The character of the city is still very much influenced by the large student population, and it is home to lively political and nightlife scenes.