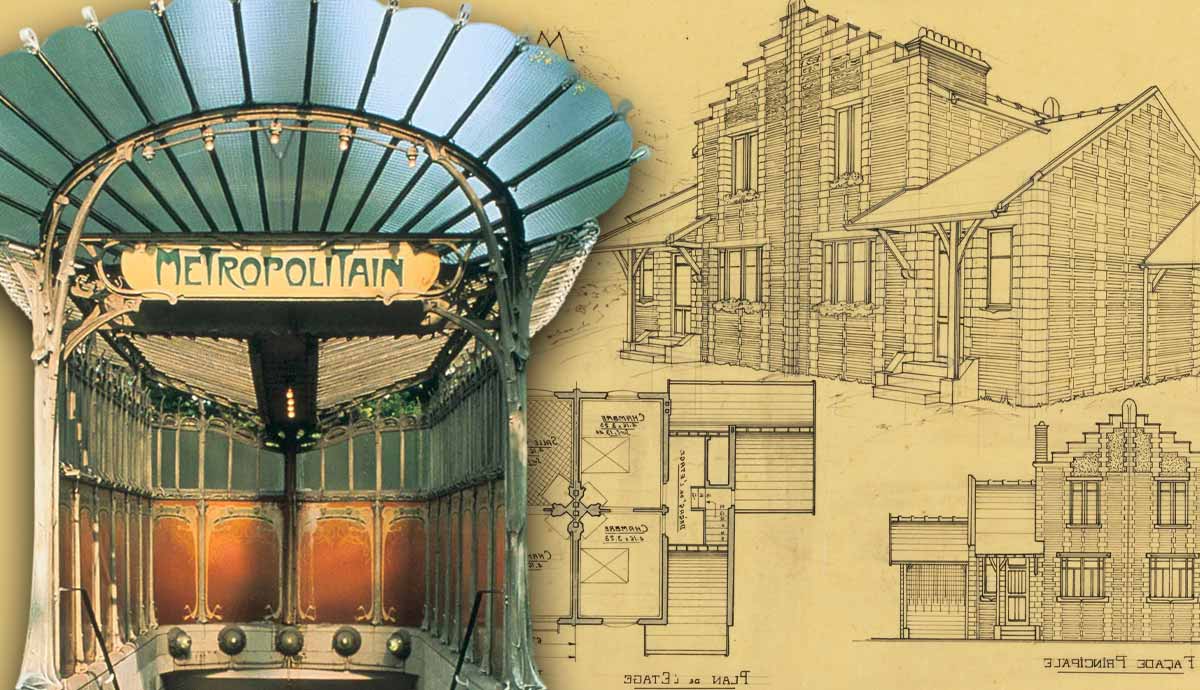

The signature design of Parisian subway entrances by Hector Guimard is among the most recognizable in the history of modern design. Still, the name of their creator sounds unjustly unfamiliar to the masses. Guimard was a revolutionary architect and the proponent of functional, affordable, yet aesthetically refined housing for the modern era. Yet, only a handful of his projects remain intact and appreciated. Read on to learn more about Hector Guimard and his works.

Hector Guimard: The Art Nouveau Legend

Born in Lyon in 1876, Hector Guimard had little to no artistic background, raised in the family of a doctor and a seamstress. Still, he showed an early inclination towards decorative art that allowed him to study it professionally despite limited financial means. By the age of 20, he became one of the best students in the Paris School of Decorative Arts and even managed to travel around Europe using scholarships and stipends. Eager to continue his studies, he enrolled at the most prestigious French art institution Ecole des Beaux-Arts, but never graduated, dropping out to work for a construction company.

During the first decade of his work, Guimard worked with variations of architectural style implemented during the Haussmann reconstruction of Paris. He mostly accepted commissions in the central areas of Paris: as a teenager, he ran away from home and settled in the house of his godmother, a wealthy landowner, who helped him obtain an education and make connections. As a result, Guimard became almost native to this area, clearly understanding its infrastructure, needs, and habits of the locals.

Still, his signature style did not form until his 1895 trip to Belgium. There, the Art Nouveau architecture was on the rise. The whiplash lines and ornaments of these unusual buildings mimicked nature and aimed to surpass it. They celebrated human creativity and skill, blending the influences of Rococo style, Egyptian art, and Neo-Gothic dramatism. Guimar believed that natural forms held the key to all architectural principles and human needs and only needed to be translated into the language of modern materials.

Castel Beranger, 1895-98

The thirty-six apartment block in central Paris became the turning point in Guimard’s career. The architect, who was only thirty years old at the time, found inspiration in Belgian Art Nouveau mansions and convinced his commissioner to experiment with form and decor. A seven-story building even had an installed lift, which was unusual at the time. Guimard mixed the radical excess of the Art Nouveau architecture with the aesthetics of Medieval castles, creating an abundantly decorated yet comforting space.

To place such a structure in the 16th arrondissement was ambitious on its own: this part of the city was known and still remains famous for its conservative and grandiose architecture. The playful Art Nouveau structure with curved stairs and fountains felt foreign and overdressed among its older neighbors. Guimard designed every element possible—from the facades to the doorknobs and furniture—to ensure a consistent and multi-dimensional experience from his building. He settled in one of the top floor apartments, with his close friend, the famous Pointillist painter Paul Signac, as his neighbor.

Paris Metro

The Beranger project brought fame and recognition to Guimard and helped him win the most iconic project closely associated with his oeuvre and legacy. After the Castel Beranger success, Guimard easily won the city council commission for the design of the underground train system. Apart from Guimard’s fame, the council chose him for political reasons. At the time of the Metro construction, the Paris city council was comprised of Socialists whose views the architect shared. Guimard aimed to democratize Art Nouveau, making the complex aesthetic transgress the boundaries of class and education, and the project of public transportation would be the perfect opportunity.

Guimard understood that the underground system would be used primarily by the working class, so he relied on affordable and recognizable industrial materials. He assembled each subway entrance from a set of mass-produced cast iron pieces, which varied in form and decoration. He developed a typeface for the signs and even installed signal lights that would alert passengers above about the train approaching underground. The abundant decoration, reminiscent of Eastern architecture and overgrown gardens, made Art Nouveau accessible and affordable for the wider public.

Still, despite the popularized aesthetic, Guimard’s colleagues and critics criticized the iconic entrances. Some believed that the curvy font was too hard to read, and others complained about the dark green color, which was indiscernible from its surroundings. Upper-class Parisians argued that the curvaceous arches ruined the pompous facades of elite neighborhoods.

Humbert de Romans Hall

The enormous and lavish music hall Salle Humbert de Romans, with eleven hundred seats, an organ, marble, mahogany, and orange glass decoration, was perhaps Guimard’s most ambitious and complex project. Yet, like most of his other work, it seemed to be doomed from the start. After years of negotiations, design, and construction, the hall stood still for only four years. In 1905, the owner demolished it to build a tennis court.

Initially, the idea of building a music hall came from a Dominican monk who ran a school in the same prestigious 16th arrondissement. The monk, known as Father Lavy, envisioned a concert facility to perform church music and chorals. The Paris Archdiocese refused to fund the project, so the money was raised from private sponsors from Father Lavy’s circles. To ensure the proper acoustics, Hector Guimard invited the famous composer Camille Saint-Saens as a consultant. Initially, the opening was planned for the 1900 Paris World Fair but was delayed until November 1901. Father Lavy did not manage to enjoy his creation, as only a month later he was banished to Constantinople, criticized for his enormous spending and vanity.

Post-World War I Housing: The Revolutionary Project by Hector Guimard

Still, the most underrated accomplishments of Hector Guimard were related not to the Art Nouveau period but to the years following the end of World War I. By that time, Art Nouveau fell out of fashion. The aesthetically overwhelming style had worn out its audience, and wartime scarcity brought an end to frivolous excesses. World War I left many regions of Europe, including Northern France, devastated. People from the war-affected areas desperately needed new housing and infrastructure.

Hector Guimard was among the ones seeking immediate solutions. To facilitate construction, he invented the concept of modular components: pre-designed elements of buildings that could be assembled in days, with no measurements or extra materials needed. Like a box of Lego bricks, Guimard’s elements could form any type, size, or configuration depending on his client’s requirements. He was enthusiastic about the possibilities of such a method, but for years, he remained the only one who had used it.

After the war, Guimard’s signature aesthetic became more somber and minimalist, focusing on function before form. He was truly the first architect to offer concrete as a cheap and functional material, years before Le Corbusier and the Brutalists. His keen attention to detail demonstrated in the complex Art Nouveau designs once again manifested itself, this time in meticulously thought-through elements of construction and daily use that would make his projects not only easy to build but comfortable to inhabit. Although Guimard designed affordable and simple housing, he never thought of making them identical. Every house had distinctive, customizable elements to create a diverse and engaging yet stylistically matching cityscape for its inhabitants. Unfortunately, Guimard’s housing projects remained mostly theoretical, deemed too innovative and unusual.

Guimard’s Final Years in New York

In 1909, Guimard married an American painter, Adeline Oppenheim, who came to Paris to study art. Her work was relatively well-received and mentioned by her contemporaries in several books on outstanding woman painters. The couple struggled with money as Guimard was replaced by other architects who were younger and more fashionable. Mostly, their financial support came from Oppenheim’s father, a New York banker. In the early 1930s, the couple witnessed the rising anti-semitic hostilities and the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany.

Due to Guimard’s political affiliation and Oppenheim’s Jewish origins, the couple decided to move to the USA in 1938. Only four years later, Guimard died there in complete obscurity. Following his death, Adeline Guimard-Oppenheim transported his entire archive, including designs, blueprints, drawings, and notes, to New York. Her dedication helped preserve Guimard’s body of work through the years of his European fall from grace and the dramatic events of World War II.

Hector Guimard’s Legacy Demolished

Still, the architectural legacy of Hector Guimard mostly remained in the form of his blueprints and plans. After the war, Adeline attempted to open a Guimard museum in one of his buildings, but the authorities refused the idea. By the 1960s, most of his iconic buildings were either destroyed or completely reshaped. The original metro entrances designed by Guimard have mostly been demolished or given away to other cities to strengthen cultural ties. Today, only one original entrance remains completely intact, 88 are partially preserved, and others are installed in Canada, Portugal, Russia, and the USA.

The architect’s widow donated most of his archives to several US museums, including the Museum of Modern Art and the Cooper Hewitt Design Museum. These institutions helped re-establish Guimard’s reputation in the 1970s after a series of Art Nouveau exhibitions attracted the attention of European officials. Today, the few remaining buildings are protected by the French state as outstanding cultural heritage.