When it comes to underrated and underappreciated monarchs, King Henry III of England tops the list. All that is typically mentioned when glossing over Henry’s reign is that he had some troubles with the De Montfort family, the fact that he had an exceptionally long reign for a medieval monarch, and that he was a son of one of England’s lowest-regarded monarchs (King John) and a father of one of the most highly-regarded monarchs (Edward I). However, as we shall see, there was far more to Henry III’s reign than this.

Henry’s Early Life

Henry was born on October 1, 1207, in Winchester Castle, in Hampshire, England. He was the eldest son of King John of England, and his mother was John’s second wife, Isabella of Angoulême.

Unfortunately, very little is known of Henry’s early life as he was thrown into kingship aged just nine years old. However, it is known that he was raised in and around the Hampshire area in the south of the country, away from King John’s court. As a result, he likely had a much closer relationship with his mother than with his father.

In 1212, Henry’s education was entrusted to the Bishop of Winchester, a man called Peter des Roches. As part of this education, Henry was given military training and also taught how to ride a horse.

Henry’s Early Rule

Henry’s father, King John, died on October 19, 1216, aged just 49, which left the nine-year-old Henry as King of England. Henry was staying in Corfe Castle with his mother when he heard the news. On his deathbed, John had requested that Henry be placed under the guardianship of William Marshal, one of the greatest knights of the Middle Ages. This was one of the most important moves that John had made in his tenure as king.

Leading loyalists to John’s cause immediately crowned Henry as king, and he became King Henry III of England. Marshal knighted young Henry, and his official coronation took place at Gloucester Cathedral on October 28, 1216. Few knew then that the young boy sitting on the throne would go on to rule for another 56 years, making it the longest reign of any English monarch in the Medieval Period.

Because Henry was not yet a man, he was placed under a minority rule, meaning that others ruled in his name for him because he was unable to do so. Naturally, William Marshal was one of the men chosen to lead young Henry’s government. When he was appointed to do so, he chose to lead the king’s military efforts, while transferring guardianship of the king to Peter des Roches.

Henry’s Early Battles

The fact that the aging William Marshal had placed himself at the head of Henry’s military command was an incredibly astute diplomatic move. Less than a year into Henry’s reign, trouble began brewing, largely thanks to the issues left behind by the Magna Carta. The Magna Carta had been reissued in early 1217, giving birth to the idea of Parliament: that the king was the highest member of the council through which England should be governed.

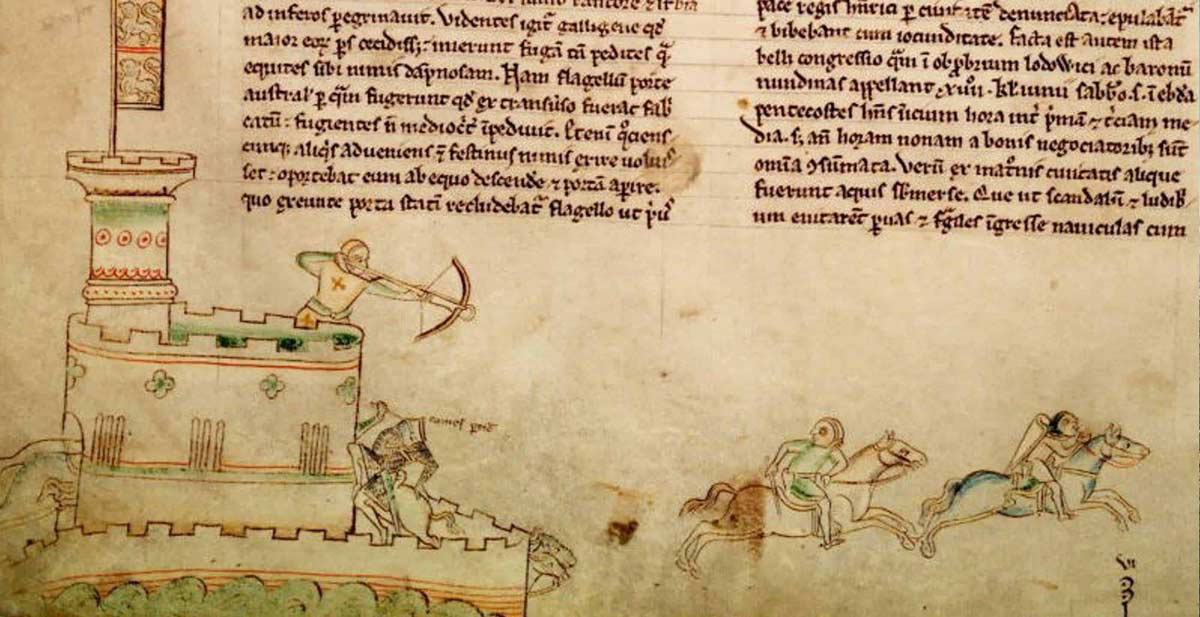

William Marshal saw victory later in the year as he led a Royalist force at the Battle of Lincoln on May 20, 1217, against Prince Louis of France’s forces, who were still trying to force his claim to the English throne as he had done during King John’s reign.

Hubert de Burgh, the Justiciar of England, also saw off a Capetian force at the Battle of Sandwich, off the Dover coast on August 24, 1217.

Despite the initial successes listed above thanks to Henry’s governors working together, their relations with one another soon soured. The two who came to loggerheads most often were Hubert de Burgh and Peter des Roches, and by 1223, des Roches had attempted to persuade Pope Honorius III to get rid of Henry’s governors.

Ultimately, this plan backfired, and de Burgh was the one who eventually ousted des Roches from his seat of power. However, Henry had finally turned 16 and was fit to rule. What many historians regard as King Henry III’s “true reign” was about to begin.

The French Problem

By January 1227, Henry had full control of his government. What Henry did excellently was that despite his minority coming to an end, he still listened to his advisers, which most likely contributed to him becoming such a successful monarch.

Like many medieval English kings, France was a contentious issue. After his father had just about lost the entire Plantagenet Empire on the continent, Henry had to, as he put it, “reclaim [his] inheritance.”

In 1226, King Louis VIII of France died, leaving his nine-year-old son Louis IX as heir apparent. The young King Louis was in a dangerous position, and a weak position, to defend his realm. In 1228, Peter I, Duke of Brittany openly paid homage to Henry III, and Henry saw this as the time to strike.

However, Henry took too long in his preparations, and by the time he did invade France in May 1230, the campaign achieved nothing. He ended up simply signing a treaty with Louis IX until 1234. In other words, it was a huge waste of resources.

Political Strife at Home

Not all was well at home, either. Henry’s chief minister, Hubert de Burgh fell from power in 1232; a year prior, his old enemy, Peter des Roches, had returned to England from the Crusades with several supporters for his cause.

Hubert decided to seek sanctuary in Merton Priory, but Henry had him imprisoned in the Tower of London instead. Des Roches then took over Henry’s government, but it was not long before he was on a power trip.

Many barons and earls who had supported de Burgh found their lands and titles being stripped by des Roches, and many (including Richard Marshal, son of William Marshal) complained personally to the king that he was not doing enough to protect their rights. This turned into a full-scale civil war between Des Roches’s followers and Marshal’s followers.

However, it was thanks to the intervention of Edmund of Abingdon, the Archbishop of Canterbury, that the conflict came to an end after he held a series of councils in 1234. Henry dismissed des Roches, and for the rest of his reign, he ruled the kingdom personally, rather than through senior ministers.

Henry’s Marriage and Family

Henry married Eleanor of Provence in 1236, a political marriage that would gain the English king credibility with noble families in south and eastern France. Eleanor would go on to become one of the most formidable medieval queens, with some historians claiming she was more hard-headed and determined than her husband.

Together, Henry and Eleanor had five children—the eldest of whom, Edward, would go on to reign as King Edward I of England.

Edward was an unusual name for an English monarch to give to their children in the mid-13th century (the Anglicized Edmund was often preferred), but Henry III’s interest, and borderline obsession, with Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-66) led to Edward becoming the joint-most popular name for English/British monarchs alongside Henry and a name that we often associate with the Middle Ages, thanks to the three Edwardian Kings (r. 1272–1377), who ruled for just over 100 years consecutively.

Henry’s children went on to form excellent diplomatic relations. As well as fathering a king of England, his eldest daughter Margaret went on to marry Alexander III of Scotland, his son Edmund was the founder of the House of Lancaster, while his daughter Beatrice went on to marry John II, Duke of Brittany. His youngest daughter, Katherine, sadly died as a child.

The Turbulent 1240s

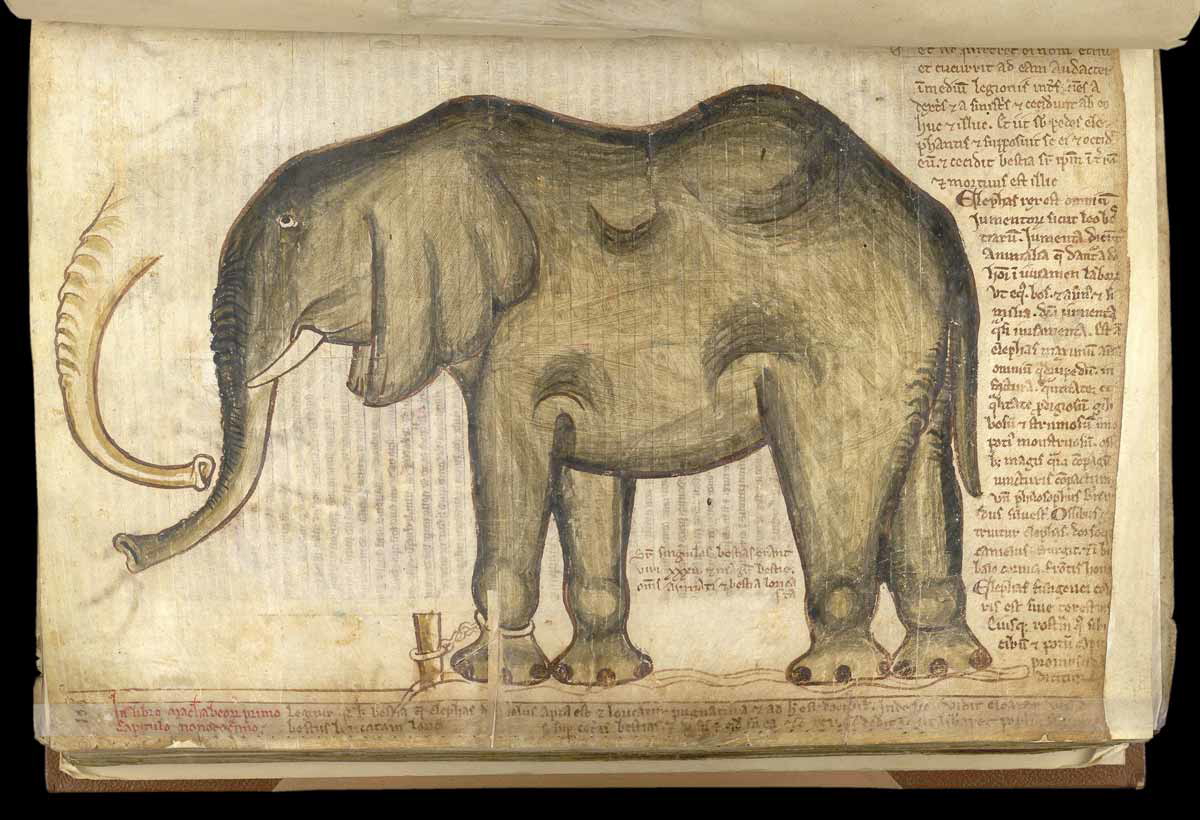

While the 1230s had generally been an era of peace for Henry (they included the establishment of London’s first menagerie in the Tower of London), the 1240s were an entirely different story.

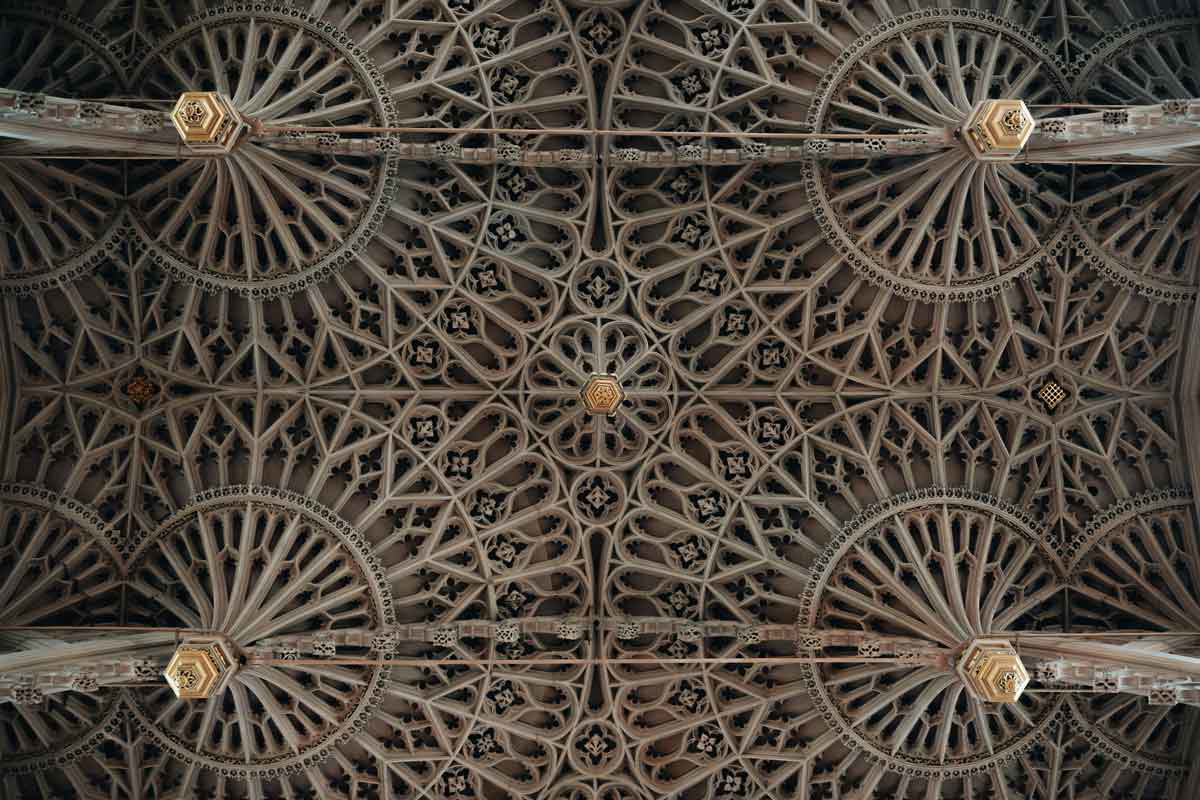

One major event came in 1245, which was when Henry began the construction of Westminster Abbey, which almost bankrupted the Crown. It would take another 25 years for the abbey to be completed. Following the Magna Carta, the barons had much more of a say in the Crown’s finances and how money was spent, and this took a turn for the worse when, in 1247, the barons invited Henry’s half-siblings over from France.

The Lusignans (his mother’s children from a previous marriage), assumed high political positions, which aggravated the barons. They felt that foreigners could not naturally assume high positions in a different country than their own. The leader of the barons was one of the most famous names in medieval English history: Simon de Montfort.

This is perhaps the most ironic thing—de Montfort was French, yet was leading a nationalistic English cause. Having been made Earl of Leicester in 1231, de Montfort went on to marry Henry’s younger sister, Eleanor. Henry then made him Governor of Gascony but sacked him from this position when he lost the territory in 1252.

De Montfort then became the ideal leading figure for the barons’ cause.

Baronial Troubles

Things finally came to a head in 1258, when the barons essentially took control out of Henry’s hands and into their own.

The Provisions of Oxford in October of the same year asserted the barons’ authority and representation in Henry’s government, as well as their ability to press concerns in opposition to those of the sitting monarch.

A year later, these were followed by the Provisions of Westminster, which further enforced the Oxford Provisions as well as enforcing taxation reforms. Henry was outraged that power had been taken out of his hands and this again led to another minor civil war, which came to be known as the Second Barons’ War (1264-67).

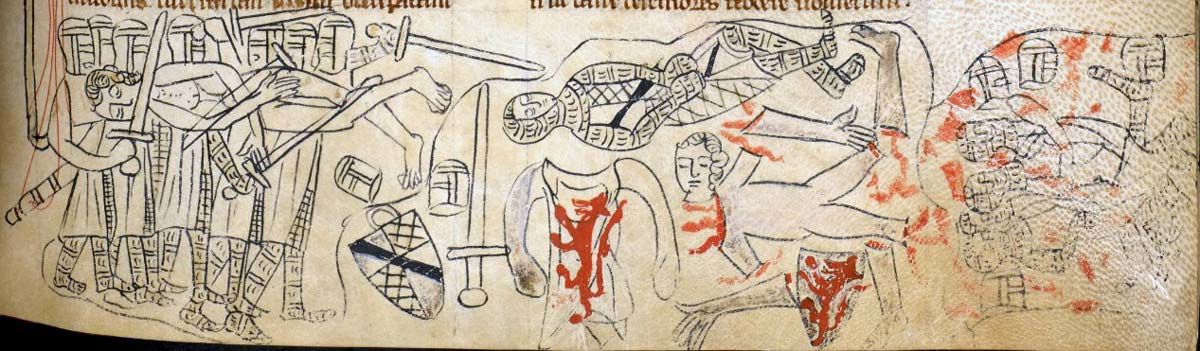

The baronial leader, Simon de Montfort, led the rebels against Henry. De Montfort was not just experienced politically, but militarily too—he had been on crusade and knew how to fight. At the Battle of Lewes (May 14, 1264), de Montfort’s forces were victorious against the Royalists, which included Prince Edward, who was captured.

Edward escaped from captivity and managed to raise another army in a year. The opposing sides met again at the Battle of Evesham on August 4, 1265, which was one of the turning points in Henry’s reign. Not only had Prince Edward shown his prowess on the battlefield by winning the skirmish, but de Montfort was killed and dismembered on the battlefield.

It was not until 1267 that the war finally ended with the Statute of Marlborough (similar to how the Magna Carta had ended the First Barons’ War half a century earlier).

Henry’s Death and Legacy

The king was aging by this point, but he did live to see his beloved Westminster Abbey completed in 1269, which was arguably the grandest church in Europe at the time.

Henry eventually died aged 65 on November 16, 1272.

But what legacy did Henry III leave behind? Most historians gloss over his reign as it is generally seen as long but uneventful. However, this is not the case at all. Henry had the misfortune of being situated between two kings at opposite ends of the scale—the terrible King John at one end and the glorious Edward I at the other.

However, Henry’s reign should not go unnoticed. While he had problems such as the way he treated the Jewish community (advocating for them to wear badges, much like a particular German leader did almost 700 years later), and issues with the barons, overall, Henry was a good king.

He founded Westminster Abbey, dealt with rebellion very calmly, listened to his advisers after his minority ended, and established diplomatic relations throughout Europe among his children. And, if you’ve ever enjoyed a visit to a zoo in the UK, remember that King Henry III founded the very first one in the 1250s!