Throughout history, a number of trade goods have transformed cultures, established ties between civilizations, and even helped start wars. From the opium that encouraged the British Empire to expand its borders to the precious whale oil that pushed sailors to explore uncharted waters, these commodities were much more than trade goods; they changed the world.

1. Guano: More Valuable Than Gold

Since human civilization began farming, those who worked the land were largely at the mercy of the weather and the inherent mineral properties of the soil they farmed. This was the case for thousands of years until guano changed the way the world grew crops. The accumulated waste products of bats and seabirds, guano, has an exceptionally high concentration of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium. These minerals are vital for plant growth and make guano the perfect fertilizer. Aside from farming, guano was also traded as an ingredient for the production of gunpowder.

For hundreds of years, guano was used by cultures in modern-day Peru to boost the crop yields of farms located in relatively infertile areas of the Inca Empire. However, after European explorers encountered this practice in the 19th century, the global trade in guano took off. The use of guano as a fertilizer allowed European nations to boost their crop yields to feed their growing empires and greatly contributed to the modern farming practices we still use today. However, the global trade in guano steadily declined as seabird colonies began to collapse due to the over-exploitation of the mineral reserves. In 1910, after an artificial method of extracting nitrogen and other minerals from the atmosphere was developed, the global trade in guano became a thing of the past.

2. Whale Oil: Lighting the World

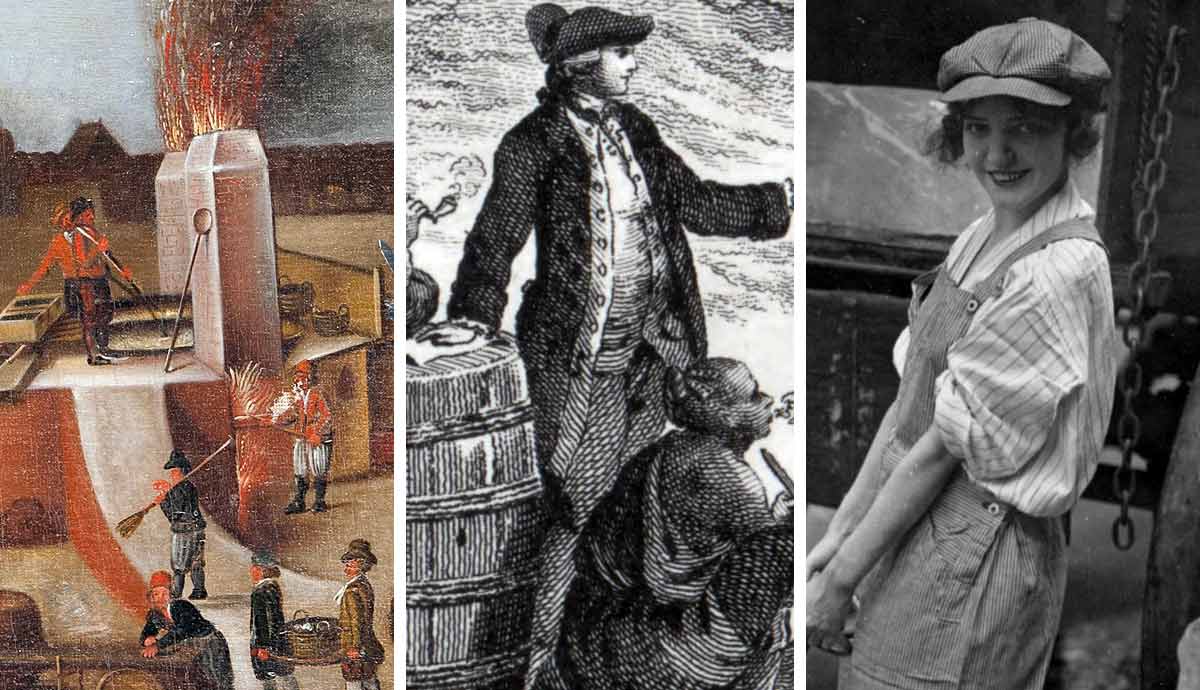

Before the advent of gas and electricity, the streets of major cities were primarily lit with whale oil. For centuries, this valuable commodity was extracted from baleen whales and sperm whales. The oil was mostly used to make soap and lamp fuel from the 16th century until the late 19th century. Moreover, whale oil was a highly sought-after lubricant for mechanical instruments, as well as a vital ingredient for varnish and sailing cloth. As industrial ingenuity increased and the global trade in whale oil became more lucrative, myriad new ways to use whale oil were invented. For example, during both World Wars, whale oil played a crucial role in the creation of explosives, and throughout the 1960s, whale liver oil was a highly significant source of Vitamin D.

During the global whale oil trade, the finished product was typically created at sea aboard massive industrial whaling ships, which used steam pressure to render a whale carcass into valuable oil. However, as overfishing led to an increase in the price of whale oil, consumers sought cheaper alternatives. Eventually, all of the most important uses of whale oil were replaced with petroleum alternatives, and the industry steadily collapsed.

3. Salt: White Gold

Before the advent of commercial refrigeration, one of the only ways to preserve food was to extract moisture using salt. For thousands of years, the global salt trade was a key driving factor for the development of civilizations in the ancient world. For centuries, the trade and production of salt played a key role in the economies of the Ancient Greeks, Tamils, Romans, and Chinese. Salt was such an important good for the early Romans that roads were constructed leading from the Adriatic Sea to Rome in order to allow for faster transport of sea salt.

Notably, the modern word “salary” derives from the Latin word for salt. However, there is very little evidence to support the notion that Roman legionaries were paid in salt. Their salary was paid in currency and was often referred to as a “solarium” as it may have been used to purchase salt for food preservation. During the latter period of the Roman Empire and continuing into the early Middle Ages, salt was a highly traded commodity, which was transported along salt roads across Europe. However, as industrial production and new methods of food preservation became prevalent, the value of salt plummeted, and a global trade network became a preserve of the ancient world.

4. Ambergris: Perfume From the Sea

Ambergris is perhaps one of the most obscure forgotten trade goods. The solid waxy material known as ambergris is found in the intestines of sperm whales and is a byproduct of the digestive process. In Europe, the global trade in ambergris was largely driven by the perfume industry as it was used to stabilize the ingredients in high-end fragrances. In Asia, ambergris had myriad uses and was employed in traditional medicine and even as a food flavoring. Ambergris is found washed up on shores around the world, and its name comes from the French word “gray amber” due to its similarity to the natural mineral found along the North Sea. Ambergris is a chemically complex mix of acids and cholesterols that increase in potency once dried. Today, the properties of ambergris are replicated by synthetic materials.

5. Beaver Pelts: The Key Commodity of the Fur Trade

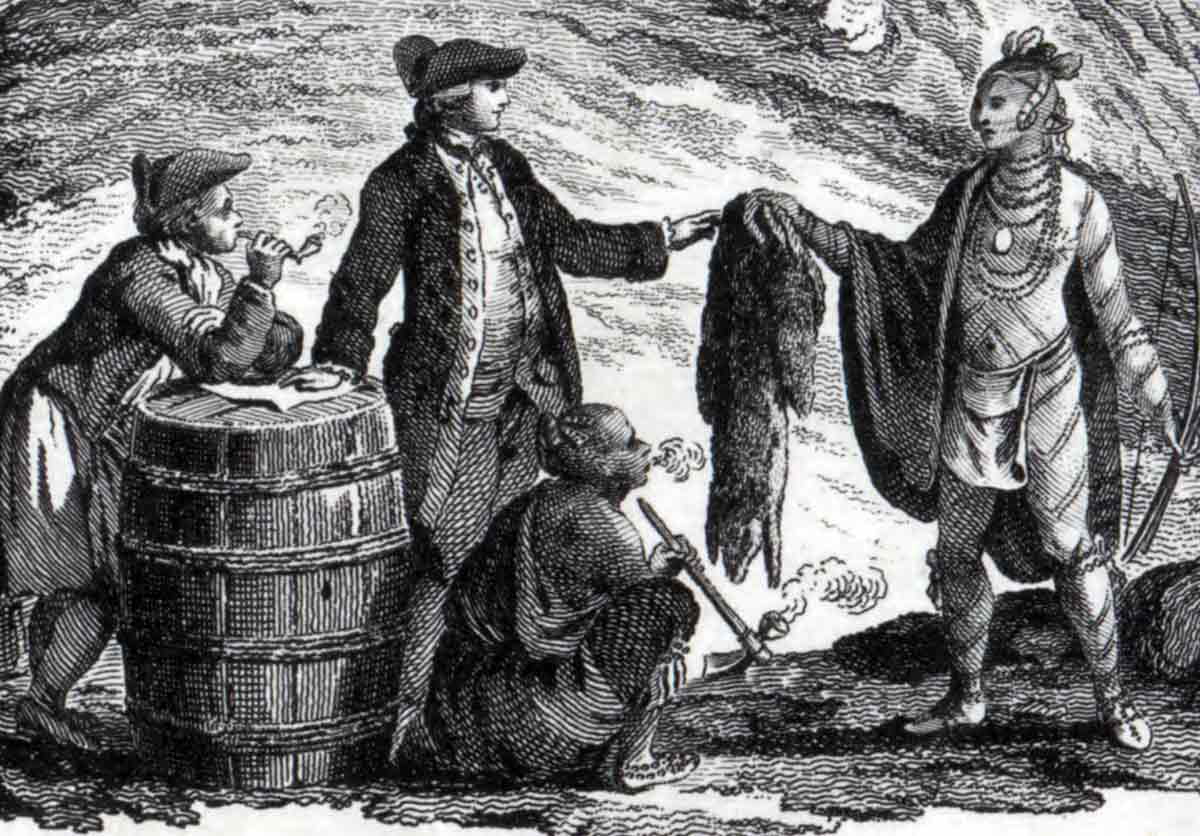

The economy of the early North American colonies, especially Canada, relied heavily on the trade of beaver pelts. The creation of an entirely unique currency, known as the Made Beaver currency by the Hudson Bay Company—used to standardize the price of beaver pelts and distribute the wealth of the fur trade among hunters—clearly shows how vital trade in beaver pelts was to the early settlers. Beaver pelts were primarily used to make hats due to the length and composition of the fur. Global trade began in earnest around the 16th century as wealthy Europeans looked to the relatively tariff-free economy of North America to make their fortune.

During its peak, the global beaver pelt trade contributed to a number of armed conflicts, such as the French and Indian War and the Beaver Wars. The trade reached its peak at the beginning of the 19th century and steadily declined as European fashion evolved and cheaper synthetic alternatives replaced expensive animal furs.

6. Ice Blocks: Cold Gold

Before the refrigerator made it readily accessible, water ice was a relatively rare commodity across large parts of the world. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the ice trade in Norway and the United States involved harvesting naturally occurring ice from mountain ponds and streams, storing it in an ice house, and then shipping it across the world. One of the pioneers of the ice trade was Frederic Tudor, who started shipping ice blocks from the northern provinces to the Caribbean.

As the ice trade grew, a huge number of frozen blocks were harvested from the Hudson River and Maine and shipped from New York to cities around the world. The abundance of ice allowed the brewing, fishing, and meatpacking industries to expand considerably, opening up new markets and enabling business to continue during the summer months. At the end of the 19th century, the ice trade in the US was worth almost thirty million dollars and employed nearly one hundred thousand people. The global ice trade collapsed in the first half of the 20th century as artificial refrigeration took off and allowed ice to be produced regardless of location.

7. Opium: A Driving Force of Imperialism

The opium poppy, which originated in Turkey, was first mentioned by the Greek philosopher and physician Dioscorides in the 1st century CE. The opium poppy was used in ancient medicine as a painkiller and panacea. Until the late 7th century, the opium trade was localized to Mesopotamia and Greece, after which it slowly spread out and made its way to China and India, where it was used in a variety of traditional medicines. Throughout much of history, opium was taken orally as a panacea and was not potent enough to cause addiction.

However, as tobacco smoking became more widespread in Europe and the global trade in tobacco products became lucrative, the practice of opium smoking also began to develop. The practice was particularly popular in China, where opium smoking became popular, and by the 17th century, addiction to opium-laced tobacco was a common occurrence. During the 18th century, European imperial powers, especially Britain, sought to take advantage of the lucrative opium market in China and began trading the narcotic in exchange for tea and silk. The opium trade between Britain and Chinese merchants caused serious problems for the Chinese authorities, who sought to eradicate opium addiction by restricting trade. This resulted in the Opium Wars, which ended with Britain winning the right to trade the commodity freely in Chinese ports.

8. Indigo: A Forgotten Cash Crop

Throughout history, various cultures have used indigo to dye clothing. Evidence of the earliest known indigo production can be found in Peru, dating back almost six thousand years. In China and Japan, indigo has long been used to dye fabrics, especially silk, with India being at the heart of much of the ancient indigo trade. Historical records indicate that the Ancient Greeks and Romans imported much of the indigo from India, which was considered a luxury commodity.

During the Middle Ages, across Europe, the woad plant was used as a substitute to dye clothing instead of expensive imported indigo. However, after European explorers established sea routes to India in the early 16th century, the production of indigo grew rapidly. At the height of the indigo trade, nearly ten thousand square kilometers of Indian land was dedicated to the growing of indigo. As cheaper synthetic alternatives became more readily available, the global indigo trade steadily declined.