While the native Irish language thrived in Ireland until the 16th century, it became nearly extinct by the 20th century due to English colonization. However, it has recently recovered due to modern patriotic movements that link the language to the Irish national identity. The language has many names: Gaeilge is the name used by speakers, whereas Irish is what it is called in English. It is also commonly called Gaelic, but this is actually the term for the language of Scotland, which has a common lexical ancestor with Irish, known as Goidelic. Throughout history, the evolution of the Irish language serves as an analogy for the Irish battle for independence.

Proto-Celtic Tongues

Irish evolved from Proto-Celtic languages, a branch of the Indo-European family, which were once widespread across Western Europe in Roman and pre-Roman times. Today, they are mainly found in the British Isles and Brittany in northwestern France.

The original Celtic languages can be divided into two groups, Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic, based on geography and historical period. Continental Celtic refers to the languages of the Keltoi and Galatae, as described by classical writers. Between about 500 BCE and 500 CE, these peoples lived across a vast region that spanned from Galatia in the east to Gaul in the west.

Insular Celtic includes the Celtic languages of the British Isles and Breton in France, which moved from Britain to the continent. Evidence of early forms comes from classical place-names, Latin and Ogham inscriptions, and manuscripts dating from the 7th century CE onward.

The Insular Celtic languages are divided into two branches: Irish (Goidelic/Gaelic) and British (Brythonic). British was once widespread across Britain and the Isle of Man, but later fragmented due to Irish settlement in Scotland and on the Isle of Man, as well as invasions from the south. It survived in Welsh, which has been enjoying a revival, and also continued in Cornish until the 18th century.

Archaic Irish & the Ogham Script

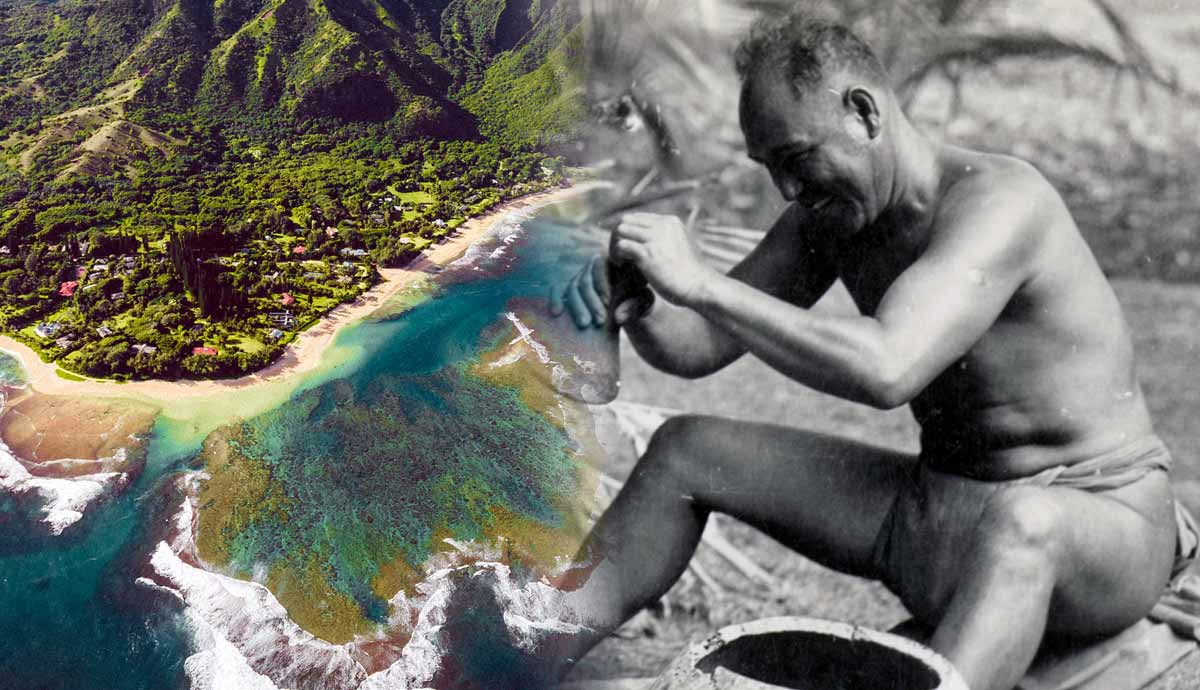

Archaic Irish was the sole language of Ireland in the 5th century CE, and gave rise to Scottish Gaelic and Manx through migration across the British Isles. Though Irish colonies also existed in Wales, little remains of their language except a few inscriptions. Overall, the Irish language was less influenced by other Celtic languages.

Archaic Irish is the oldest known documented type of the Goidelic/Gaelic language group. It was written in Ogham, Orthodox Ogham being the original form. There are around 400 Ogham inscriptions known today, with the earliest dating to around the 6th century CE, although historians theorize that it was established a couple of centuries earlier. Ogham inscriptions have been found mainly in Ireland, but also across the Western side of the British Isles, particularly in Wales and parts of Scotland.

While Latin spread with the arrival of Christianity, Ogham continued to be used for monumental and funerary inscriptions.

Old Irish

Old Irish evolved from Archaic Irish and had a relatively short life span. Written records suggest it was only used from around 600-900 CE. However, it was the first vernacular language to be widely written in Europe.

The few contemporary sources that survive consist mainly of small notes in Latin religious manuscripts. Many were preserved in monasteries in mainland Europe, having been gifted to other Christian communities by Irish missionaries. Unlike in Ireland, where manuscripts were heavily used and often worn out, those on the Continent endured because they were essentially illegible to the native populations.

Most of what is known about Old Irish has been transmitted by texts rewritten in Middle or Early Modern Irish. Many Old Irish texts, rewritten or not, were essential for recording early Irish mythology, literary narratives, and even legal documents.

Middle Irish

Middle Irish thrived between 900 and 1200 CE. The language borrowed some Scandinavian words through ongoing contact with the Vikings from the 8th century onwards. But the unique grammar of Irish remained unaffected. Despite ongoing conflict with Norse invaders, Irish literary culture thrived, leaving behind plenty of surviving manuscripts from this period.

When the Irish eventually rose up and defeated the Vikings under Brian Boru, numerous Norsemen deserted Ireland, but many others had already married into the population. This created many bilingual and cross-cultural families who could speak Irish and Norse.

Anglo-Norman settlement in Ireland during the late 12th century brought new cultural and linguistic influences. Although their arrival added to an already multilingual society, Irish remained the dominant language. Over time, even the Normans in Ireland adopted it. Their presence enriched Irish vocabulary with many loanwords, particularly in areas like law (giúistís “justice,” cúirt “court”) as well as everyday life (garsún “boy”).

Early Modern Irish

Alongside the influx of multiculturalism, the 12th century saw Church reforms that linked Ireland more closely with Western Europe. These combined pressures and changes appear to have motivated Irish scholars to standardize and refine the language, ensuring its resilience and continued authority.

Consequently, Classical or Early Modern Irish was thrust into being through a new, enforced regulation of the language. Early Modern Irish marks the shift from Middle to Modern Irish between 1200 and 1600 CE. Its literary standard, Classical Gaelic, was shared by poets from Ireland and Scotland from the 13th to the 18th centuries. Native scholars produced grammatical tracts to teach this refined form of the language to poets, professionals, and clergy.

Before the 12th century, the dialects of Ireland and Scotland were seen as one language. In the formal standard for bardic poetry, contemporary vernaculars were employed while allowing some dialectal variation. This conservative standard was taught with little change for centuries, using grammatical tracts and instructional poems in bardic schools.

Despite efforts to enforce the authority of the Irish language, ongoing English colonization led to its loss of power. This culminated in Henry VIII declaring himself King of Ireland in 1542. Although most people spoke Irish, English became essential for administration and law, preventing Irish from becoming an official language and leaving its speakers without political independence.

Decline of the Irish Language

While Irish lost much of its status under English control, it remained widely spoken in rural areas and among urban workers. However, from the mid-18th century, wealthier Irish speakers gradually adopted English, as it dominated government, trade, and high social life, making it crucial for anyone seeking social or financial advancement. Irish, increasingly seen as backwards and vulgar, was discouraged at home and actively suppressed by the Anglo-Irish authorities, especially in larger towns and cities and in the eastern regions.

The introduction of the state-funded National Schools in 1831, largely run by the Church, reinforced this shift. Irish was largely excluded from the curriculum and taught as a minor subject only after English, Latin, Greek, and French. Furthermore, the lack of an authorized Irish Catholic Bible (An Biobla Naofa) until 1981 meant that religious education was delivered mainly in English or Latin. By the end of the 19th century, Irish was a minority language in Ireland.

The Impact of Politics in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Before the Great Famine of the 1840s, Irish remained widely used in courts and commerce, with interpreters often employed and fluency among magistrates, lawyers, and jurors valued. This was because many poorer and working-class people could speak limited English, but even those who were fluent in English often asked for Irish interpreters.

However, An Gorta Mór (as the Great Famine is known in Irish), which began in 1845 and lasted until 1852, devastated rural Irish-speaking communities, causing over a million deaths and forcing another million to emigrate, mainly to English-speaking countries such as the United States and Britain. Additionally, those who were less affected by the famine were mainly anglicized upper-class professionals, which meant even less need for the Irish language.

The Irish speakers who survived often needed English to find work and integrate abroad, which weakened the transmission of Irish within families. Over time, the combination of famine, emigration, and social and economic pressures concentrated Irish speakers in poorer rural areas, accelerating the decline of Irish.

Even Irish political leaders such as Dónall Ó Conaill, known by the anglicized name Daniel O’Connell, moved toward English. Historically, Ó Conaill has been dubbed a liberator of Ireland with substantially progressive views at the time. He was and still is renowned for his opposition to slavery and his actions in emancipating the Catholic populations within Ireland. However, he claimed indifference to the abandonment of Irish, despite it being his mother tongue.

Within the Republic of Ireland

The trajectory of the language in the Republic and Northern Ireland was different, but both used it in various ways to separate themselves from Britain.

The independent Irish state was established in 1922, originally the Irish Free State, later the Republic of Ireland. Despite some leaders supporting Irish, English remained the main language of administration, even in regions where most people spoke Irish. Early efforts to promote the language, such as a 1922 decree requiring Irish versions of names on official records, were largely unimplemented, partly due to the Irish Civil War. Irish became a compulsory school subject in 1928, but this was later scrutinized. Since independence, the number of first-language Irish speakers has declined, while second-language speakers have grown.

The first president of Ireland, Douglas Hyde (1938-1945), emphasized that the Irish language transcended religion and politics. However, the Gaelic League, an organization founded in 1893 to revive the Irish language, was already being subtly influenced by Irish Republican operatives. British officials overseeing education tried to block the expansion of Irish schooling so persistently that the Lord Lieutenant, John Hamilton-Gordon, had to intervene in 1906 to enforce it.

Critics, including MP John Lonsdale and the Ulster Unionist Council, portrayed the Gaelic movement as politically motivated, claiming Irish instruction in schools was a waste of money and a tool for spreading anti-English rhetoric and republican ideas. Consequently, it was only in 2003 that the Official Languages Act reinforced Irish as an official language in public services, and in 2007, it became an official working language of the European Union.

Irish in Northern Ireland

During “The Troubles,” the Irish language in Northern Ireland became highly politicized. Many republican prisoners, including Gerry Adams, the former Sinn Féin leader, learned Irish in jail and created secret “Jailtachts” to communicate without British guards understanding them. Subsequently, the language allowed republicans to strengthen solidarity and maintain a distinct nationalist identity.

Irish also served as a symbolic tool against British influence and a means to reclaim suppressed cultural heritage. In 1969, a cooperative housing project on Shaw’s Road in West Belfast aimed to establish an urban neo-Gaeltacht, giving rise to what is now called Belfast Irish, an urban dialect of Ulster Irish shaped by the conflict. It is now the main dialect in the Gaeltacht Quarter.

The iconic Irish slogan tiocfaidh ár lá (“our day will come”) is linked to Bobby Sands, a Provisional IRA prisoner at the Maze Prison, whose organization aimed to end British rule in Northern Ireland and achieve Irish reunification. The phrase appears in Bobby Sands’ diary from the 1981 hunger strike, though Diarmait Mac Giolla Chríost traces it to an earlier 1975-77 pamphlet by Gerry Adams. Adams credits the slogan to Republican prisoners in both the Maze and Armagh Prisons.

Tiocfaidh ár lá has been used publicly by figures such as Patrick Magee after his 1986 sentencing for the Brighton Bombing, by the leader of Sinn Féin, Mary Lou McDonald, at a 2018 conference, and poet Gearóid Mac Lochlainn in his 2002 poem Ag Siopadóireacht, where tiocfaidh ár lá is retained in Irish as a symbol of rebellion even in its English translation.

Additionally, Tiocfaidh ár lá, or TAL for short, is the name of a fan-run zine for the Celtic football club. Despite being from Glasgow, Scotland, Celtic F.C. was founded in 1887 by Irishman Brother Walfrid to support Glasgow’s impoverished Catholic communities and Irish immigrants. It was named in honor of both Irish and Scottish heritage. The club still maintains strong ties to the Irish community and culture, with a devoted following in Ireland.

Irish in the Arts

Today, the Irish language is increasingly woven into everyday conversation and creative or commercial ventures, from fashion to media. Cine4 and a host of Irish film production companies have also expanded global exposure for the Irish language. The comedic biopic “Kneecap” (2024), which chronicles the formation of the hip-hop trio of the same name, has received international acclaim and garnered multiple awards.

Music has played a central role in this resurgence, particularly Irish rebel songs, which originated during periods of English and British rule and celebrate historical struggles for independence and national identity. Over time, these songs have evolved into “crossover” forms, blending traditional Irish lyrics and instrumentation with contemporary pop, punk, and rock styles.

Bands like The Pogues, originally named Pogue Mahone, a play on the Irish phrase “póg mo thóin,” meaning “kiss my a**,” the Dropkick Murphys, and the Wolfetones have brought Irish rebel music to international audiences, sustaining its cultural significance. This interplay of language, music, and modern media has strengthened the appeal of Irish among new generations, making it both a tool for cultural preservation and a medium for creative, global expression.