There are nine officially established Chinatowns in greater New York—Manhattan, Flushing, Sunset Park, Little Neck, the East Village, Forest Hills, Homecrest, Bensonhurst, and Elmhurst—but the oldest and most famous of them is in Manhattan. The neighborhood has a vibrant history and culture, including food, architecture, and the infamous tongs, marked by the tensions between assimilation and retention of Chinese identity. Like many other immigrant neighborhoods, Chinatown has had to navigate social, political, and economic obstacles, but it remains a living embodiment of the American Dream.

First Wave of Chinese Immigration

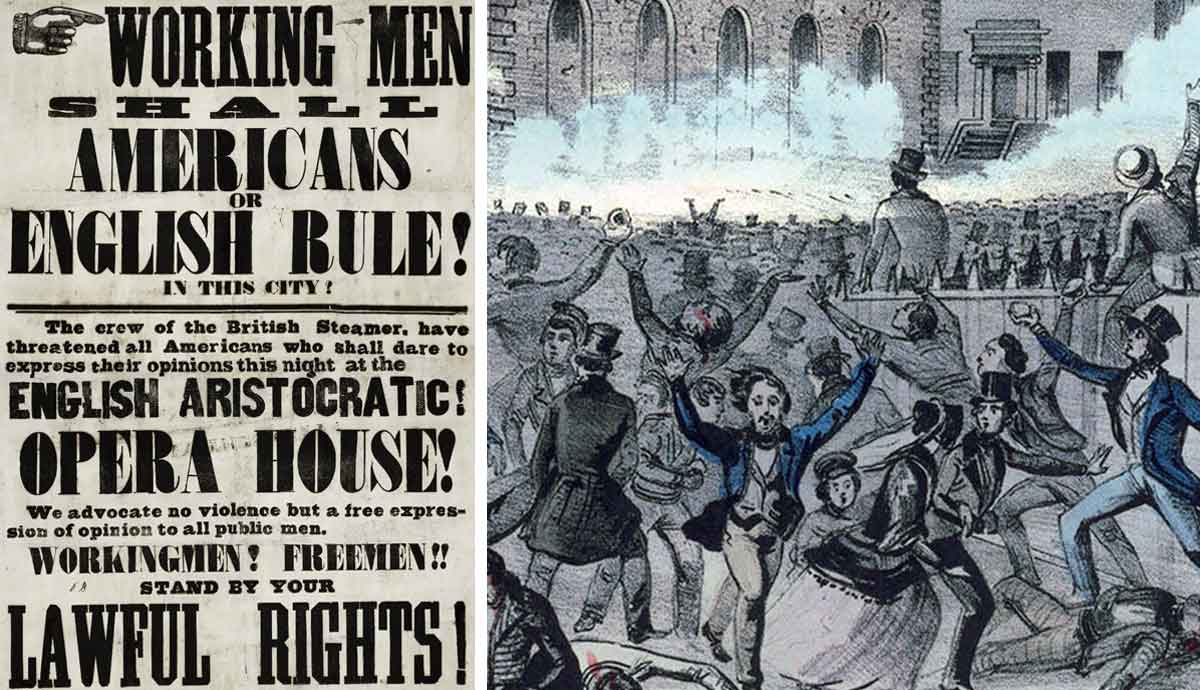

Chinese immigrants began arriving in the United States in the mid-1840s, after natural catastrophes and defeat at the hands of the British in the first Opium War led to famine and the Taiping rebellion in their homeland. They also came in large numbers after the passage of the Burlingame Treaty of 1868, which gave China Most Favored Nation status, encouraging immigration for labor purposes. Many were attracted to California’s gold fields and joined the hardscrabble communities near San Francisco and in the Sierra Mountains to pan for gold and make new lives for themselves.

Chinese immigrants also worked in large numbers on the transcontinental railroad, using dynamite and pickaxes to laboriously carve out tunnels in the mountains and lay out miles and miles of tracks. Unrecognized for their efforts at the time, they nonetheless made an indelible mark on the nation’s infrastructure and economy during the late 19th century.

Origins of Manhattan’s Chinatown

It was immigrants from the Toisan, Guangdong province who first established a neighborhood at the center of Mott, Pell, and Doyers streets in Lower Manhattan in the 1870s. Historian Herbert Asbury described Doyers Street in his famous book The Gangs of New York: “Doyers Street is a crooked little thoroughfare which runs twistingly, up hill and down, from Chatham Square to Pell Street, and with Pell and Mott streets forms New York’s Chinatown, of which it has always been the nerve center and the scene of much of the turbulent life of the quarter.”

The neighborhood soon expanded: “the lower end of Mott Street very quickly filled with Chinese…Gradually, the colony increased and spread into Doyer Street. Until now the entire triangular space bounded by Mott, Pell and Doyer Streets and Chatham square is given the exclusive occupation of these orientals, and they are fast acquiring possession of Bayard street.” It continued to grow as more Chinese laborers were pushed out of the American West, where increasing persecution from Irish Americans oppressed them both socially and economically.

Most of Chinatown’s inhabitants were men, with a ratio of 27 men for every woman. A contemporary observer offered a detailed description of the population: “three thousand, had seven hundred gamblers, four hundred and fifty hatchet men, one hundred and seventy-five merchants, seventy-five cigar makers and seventy-five vegetable growers, forty-five restaurateurs, forty-five pastry chefs, at least 20 opium dens, one annual opera, and yearly poetry writing competitions.”

Chinatown After the Chinese Exclusion Act

Prompted by growing nativist sentiment, the United States Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, the country’s first race-based immigration policy. It dealt a blow to Chinatown’s growth, as the neighborhood was still primarily men, and now fewer women could come over and start families. Those who were in the neighborhood had to stick together, which they did through the formation of cultural and social organizations. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association (CCBA) purchased a building at 16 Mott Street and set up what was known as Chinatown’s city hall, as it “meditated [sic] disputes, acted as middlemen in business transactions, and advocated for the rights of Chinese and Chinese Americans.” The building is known as the first genuine Chinese building in New York because it was an alteration of an older tenement building with Chinese ornamental and architectural design.

There were nearly 200 opium dens and gambling parlors in the neighborhood by the end of the century, and, combined with the racial prejudice of the day, outsiders conferred upon Chinatown a less-than-savory reputation. The two main tongs, or secret societies that engaged in criminal activity, often made the lurid pages of the Police Gazette, and the handful of murders that took place in the blind bend of Doyers Street gave it the nickname “the Bloody Angle.”

Often, white New Yorkers came down into the neighborhood in pursuit of a sort of touristy “slumming,” hoping to tour opium dens and murder sites. But they also came for the food, which was slowly becoming an attraction for non-Chinese patrons. According to Eater, restaurants began moving away from regional fare, and “savvy cooks reformulated dishes for non-Chinese palates.” Chop suey and egg foo young were two of these popular dishes, neither of which was traditionally Chinese.

The Early 20th Century

The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed on December 17, 1943, but immigration laws still only allowed for 105 new immigrants from China per year; it would not be until after the passage of 1965’s new immigration law that numbers increased in any meaningful way. In the early 1950s, the city put forth the China Village Plan, proposing to demolish the historic core and replace it with a housing project, but community advocates successfully fought the plan, and it was ultimately abandoned. This activism was in line with what Jane Jacobs advocated for in her seminal work The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), which sought to forestall urban planner Robert Moses’s plan to destroy the older fabric of the city in the name of “urban renewal.”

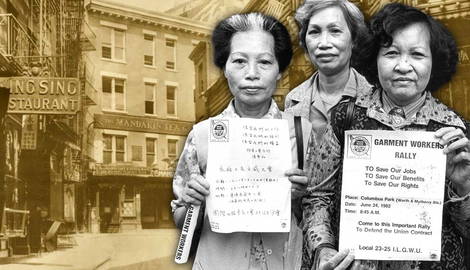

Post-1965: Expansion

President Lyndon B. Johnson and his Great Society Congress finally ended the strict caps on immigration from non-Western countries that had been in place since the 1920s. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 allowed for 20,000 new Chinese immigrants a year to come to the United States. In the late 1960s and 70s, most of them were coming from the Hong Kong and Guangdong provinces, making Cantonese the most spoken language.

By the 1980s and 90s, most immigrants were coming from the Fujian Province and settled in a part of the neighborhood that soon became known as “Little Fuzhou.” The City University of New York explains, “Many Fuzhounese immigrants had no legal statuses, and were forced into the lowest paid jobs. Their undocumented statuses also forced them to find a job a few blocks away from their ‘homes.’ These houses were usually illegally subdivided into many compartments by the landlord. Many Fuzhounese were able to learn Cantonese in order to survive in this Cantonese dominated neighborhood, but they were not able to assimilate into Cantonese culture. Therefore, a distinct new part of Chinatown known as ‘Little Fuzhou’ started to emerge on East Broadway and Eldridge Street.”

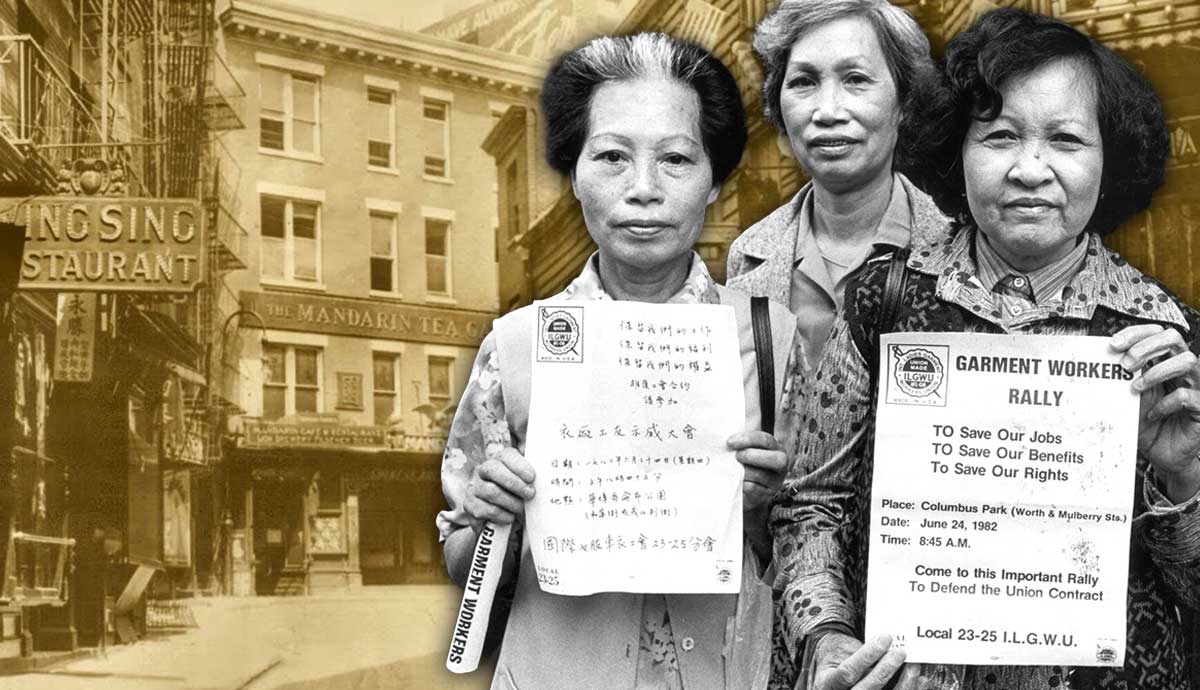

Chinatown began to expand its borders once again, spilling over into Little Italy. What began as roughly seven blocks a century earlier now grew to 55 blocks, stretching from the East River to City Hall and from St. James Place north of Canal Street. The buildings taken over from Little Italy were usually converted into garment factories and offices.

Chinatown in the 21st Century

Chinatown, as New York City’s official Department of Small Business Services report on the neighborhood states, “remains a cultural hub for Asian Americans from across the country and beyond.” Its denizens, unfortunately, suffered anti-Asian discrimination and hate crimes in 2020 and subsequent years after it was discovered that the COVID-19 virus had originated in China. In response, organizations and activists came together to, as the report says, “protect and empower the people, culture, and small businesses that make the neighborhood unique.” The state of New York awarded the neighborhood a $20 million Downtown Revitalization Initiative grant, a testament to the importance of the area to both the city and the state.

As of 2021, approximately 57,000 people live in Chinatown, and the foreign-born population in the neighborhood is 52%. Sixty percent of its residents are Asian alone in terms of race or ethnic background, the median age is 43, and 28% live below the poverty line. Challenges for the neighborhood remain, including language and cultural barriers, rising rents and other financial burdens, the density of commercial space and crowded sidewalks, and anti-Asian sentiment and crime. But the report also details several strengths, such as affordable food, good public transportation, a history of property ownership for many residents, and, perhaps most importantly, “History, culture, and intergenerational connections all contribute to a strong, deep, and layered sense of community, making this the cultural home and place of belonging and celebration for Chinese Americans and the greater Asian diaspora.”