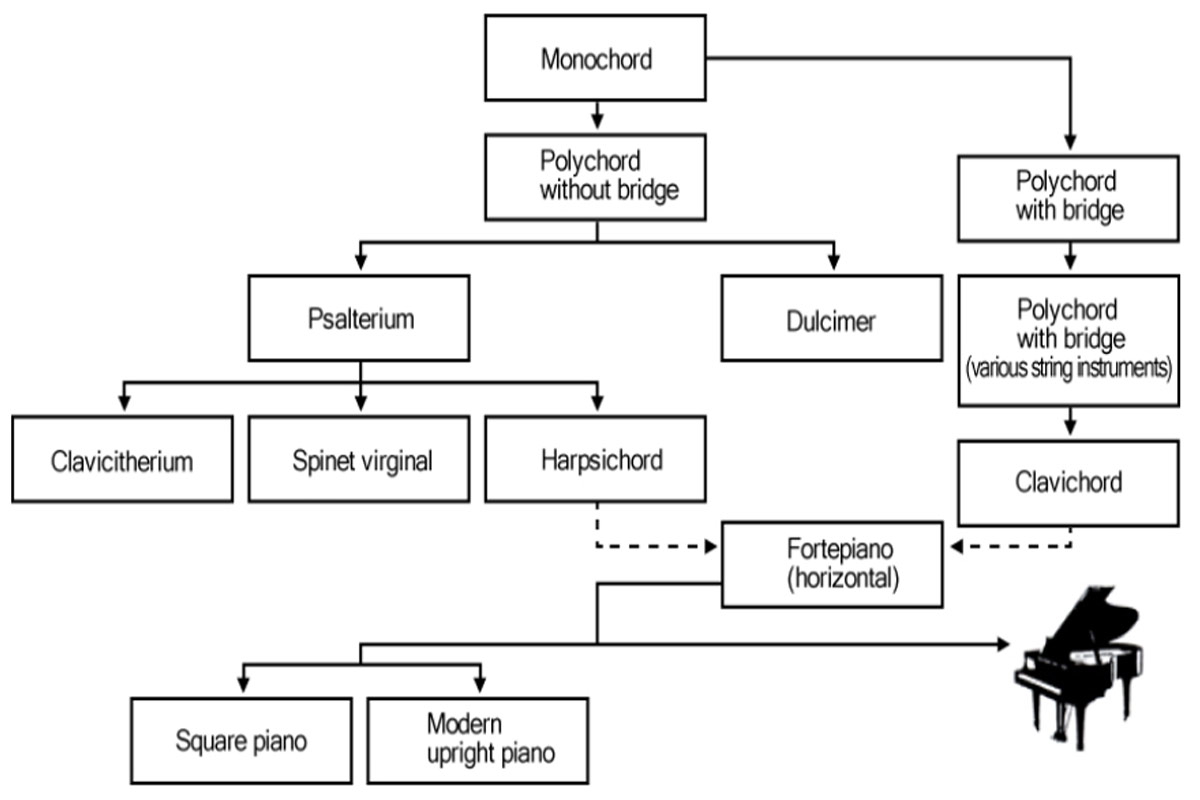

Today, the piano is one of the most common instruments found across musical genres. Yet, the piano we know and love today had a long journey before metamorphosing into its current form. Its origins can be traced back to Pythagoras’s monochord. There is a golden thread that runs through the piano’s history—strings, whether plucked or struck—are always present. Join the journey to discover more about the history of the piano from its humble beginnings to Bartolomeo Cristofori’s prototype piano to the behemoth concert grand pianos gracing concert stages and recording studios.

The Piano’s Historical Roots

Is a piano a string instrument, because it contains strings like a guitar? Is it a percussion instrument like the drums, because hammers strike the strings? It depends on who you ask… I like to think of the piano as a hybrid between a percussion and a stringed instrument.

We will start our journey with the most ancient instrument, the monochord, then proceed through the piano’s history via the clavichord and harpsichord, finally arriving at the modern piano.

Ancient Origins

Several instruments led to the invention of the modern piano. Each instrument contributed to its evolution.

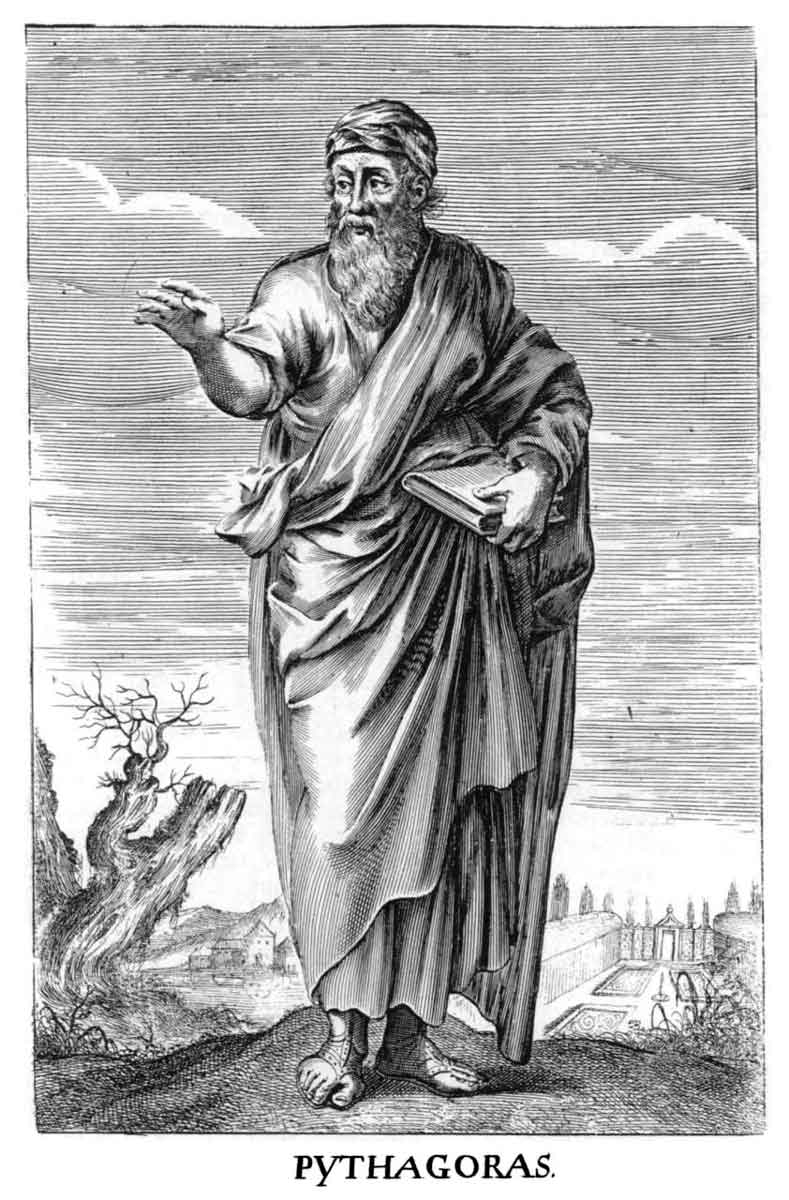

The piano’s journey starts with an unlikely candidate—the Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras. He invented the monochord as a scientific exercise to measure musical intervals (the space between two notes). Pythagoras discovered that different lengths of string produce different pitches.

When he halved the length of the string, the pitch sounded one octave (eight notes) higher. Other string lengths, or ratios, would produce consonant (pleasant-sounding) pitches. For example, reducing the string length to two-thirds (3:2) will produce a perfect fifth. Pythagoras’s findings laid the foundations of Western music and illustrated a natural, mathematical relationship between pitches.

Boethius, a late Roman philosopher, was aware of the instrument and his writings (De Institutione Musica) preserved this knowledge of music theorists into the Medieval and Late Medieval periods. Treatises on the monochord date from around 10 CE and by the late 14th century, keys were added to strike strings in a box. Another ancient instrument—the organ—inspired the addition of keys. Eventually, this became the prototype of the clavichord by the late 14th century (more on the clavichord later).

Before keys were added to the clavichord prototypes, there was the hammered dulcimer—a favorite of medieval musicians in Western and Eastern Europe. The hammered dulcimer probably originated in the Middle East around 900 CE. The instrument spread to North Africa and finally arrived in Europe during the 12th century CE, along with the Moors.

When you play the hammered dulcimer, the strings keep on resounding and the notes create a woven fabric of music that melts together. This “problem” would later be “rectified” in the clavichord and harpsichord.

German musician Pantaleon Hebenstreit designed a special dulcimer for himself. His instrument had two soundboards and was around 9 feet (3 meters) long—four times the length of a traditional dulcimer. Further, adaptations of Hebenstreit’s parts included hammers that were covered with different materials to produce loud and soft sounds. Hebenstreit’s special dulcimer did not develop into a commercial product because players required his special skills.

The idea of strings being hit by hammers shows the humble origins of the modern piano. But it would still be a few centuries before anything related to a modern piano would emerge in the workshop of Bartolomeo Cristofori.

Late Medieval and Renaissance: Strides Toward Hammer Action

While the clavichord and harpsichord have their origin in the Late Middle Ages, they flourished in the Renaissance. It was a period known for its emphasis on innovation, independent thought, and inventions that drove humanity forward.

The Clavichord: Striking Strings Becomes Possible

The clavichord changed the face and sound of music across Europe. The clavichord took inspiration from the hammered dulcimer’s hammers and the organ’s keyboard, where each key corresponded to a single note. The clavichord was invented in the early 14th century and is derived from the monochord. The harpsichord also has its roots in the Medieval Period.

It was a revolutionary instrument. When a key is pressed, a tangent—usually brass—strikes the bi-chord strings (two parallel strings tuned to the same pitch) to produce sound. The tangent remains in contact with the string, acting like a fret on a guitar.

However, the clavichord had a drawback—the instrument was not loud enough to fill a concert hall (unlike a harpsichord) and was best suited for performances at home. Despite its drawback, the clavichord had other unique features, which include a vibrato effect when the pressure on the key is varied. For the first time, players could also vary the volume by striking the keys harder or softer, however, the loudest sound a clavichord could produce was about mezzo-piano.

For around 300 to 400 years, the clavichord remained a popular instrument, because it was relatively small (before 1730 they measured around 4 feet [1.2 m] and had four octaves).

It was also more affordable than its cousin, the harpsichord, which made it an excellent choice for individuals who wanted to learn a keyboard instrument. Composers like Mozart would take their clavichord on their travels to practice while away from home.

Harpsichords: Plucking Strings and Adding Dampers

Perhaps the harpsichord (variants of which include the muselar, spinet, and virginal) is opposed to the clavichord. Instead of striking the strings, as with the clavichord, a jack or quill plucks the strings.

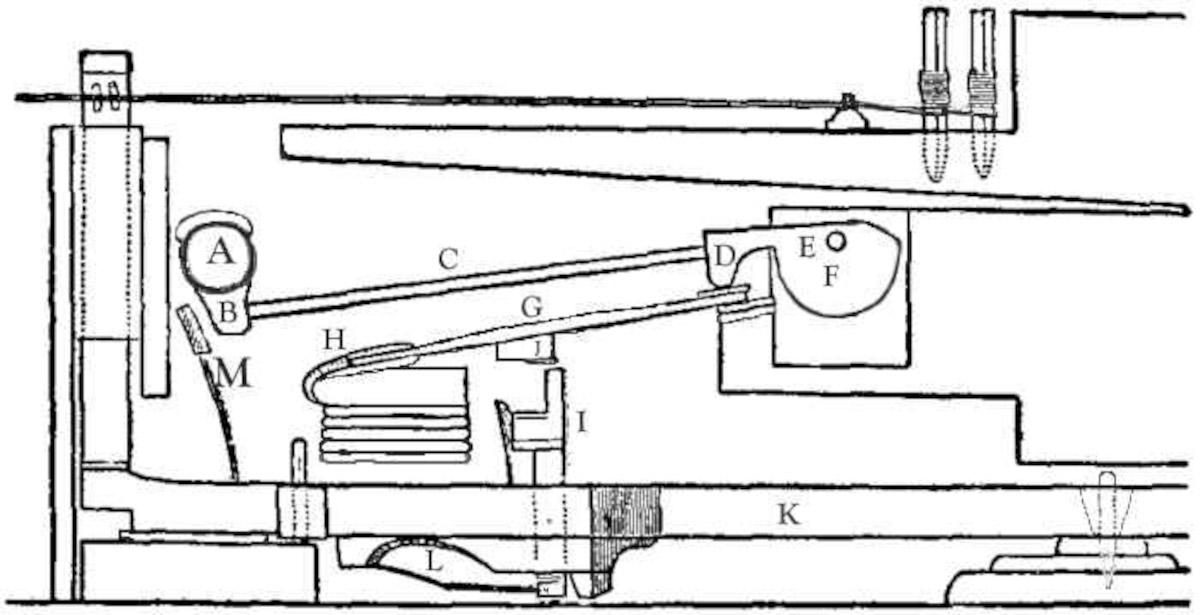

When a player strikes the key, a jack or quill is raised to pluck the string to let it vibrate. A felt damper is lifted off the strings to allow it to vibrate freely. However, the harpsichord has a much more intricate mechanism that foreshadows ideas we find in the modern piano. Apart from the jack falling back to its original position because of gravity (thank you for clarifying the concept, Iasac Newton and Leonardo da Vinci!) and weight, there is also a spring mechanism called the tongue. The tongue is another pivot mechanism that is activated by a spring that allows it to swing forward while carrying the plectrum past the string. Ultimately, this would become the “escapement” that Cristofori and later piano makers would use in their piano actions. The damper comes to rest on the string, stopping the vibration and sound.

Bartolomeo Cristofori took the best the harpsichord and clavichord offered when he invented the first iteration of the modern piano as we know it today.

Bartolomeo Cristofori’s Clavicembalo Col Piano e Forte

For an instrument that changed the face of music history in the Western world, Cristofori’s invention had a quiet genesis. It comes as a surprise because every major composer since Mozart has played the piano. Many composers were piano virtuosi, and the piano is often found at the heart of many Western classical performances.

Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731) from Padua, Italy, is often credited with the invention of the piano, or as the Medici court musician Federigo Meccoli called it, the “arpi cimbalo del piano e forte.” The exact date of Cristofori’s invention lies somewhere between 1696 and 1699, but 1700 is often taken as the year of invention.

Cristofori’s major innovation lies in the action he invented—instead of striking the keys with brass tangents or plucking them with quills, hammers covered with felt or leather were used. Further innovations included the “escapement” action where the hammer would fall away from the string. This action allows the string to vibrate freely and the piano can strike harder than a clavichord’s tangent could. Further, with all the force and speed present when the hammer hits a string, Cristofori added a “check” to stop the hammer from re-hitting the string.

With significant innovation also came criticism from one the greatest composers who ever lived. JS Bach praised and criticized German instrument builder Gottfried Silbermann’s piano, which was modeled after Cristofori’s a year after the inventor died in 1732. While JS Bach praised Silbermann’s instrument for its beautiful tone, he complained about the heavy touch and said the treble sounded too weak. One should remember that Bach was an accomplished organist and keyboard player and also built organs during his lifetime. Of course, the master’s comments took Silbermann by surprise, but he took it as sound advice and continued to improve the Silbermann pianos’ action.

Bach finally gave his approval to Silbermann’s instrument when he visited his son Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach at Frederick the Great’s palace in 1747 in Potsdam. Bach also improvised a fugue for the emperor on the improved instrument based on a theme composed by the emperor himself. Today, this work is known as The Musical Offering.

Bach’s approval of Silbermann’s improved pianos extended further—he became a sales agent for the piano and carried Cristofori’s legacy and ideas into central Europe for new generations to discover and improve upon.

The Modern Piano Emerges, ca. 1800s

Cristofori’s innovative piano design and action only became public knowledge after he received a visit from the Italian journalist Scipione Maffei. Two years later, an article appeared with drawings of Cristofori’s design. Silbermann, mentioned above, copied the design and made his adjustments to it. Other instrument makers also took the design and put their signatures on it. Thus, the English and Viennese schools of piano-making emerged.

Viennese Action Pianos

The harpsichord, which could play loud and soft, caught Mozart’s attention, and he wrote about Johann Andres Stein’s instruments in a letter to his father in 1777. The Viennese action, perfected between ca. 1780-90, was in use until 1905, while some sources mention the end of World War I.

With the Viennese or Prellmechanik action, the hammers are directly attached to the piano key and point toward the player. This arrangement allows the escapement to be placed underneath the edge of the soundboard. In a Viennese action, the hammer tends to “stroke” the string when it hits it, resulting in a gentler sound. These are pianos composers like CPE Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven would have played and composed on.

English Pianos: Heavier Designs Equal Bigger Sound

The English, not wasting time, also had a distinct action. While Viennese instruments had a more refined and somewhat softer sound, the English piano had a heftier sound which was achieved by adding iron bars to the wooden framework. The strings were also heavier, which exerted more tension on the framework, hence the iron bar reinforcements.

Beethoven was a big proponent of the pianos made by John Broadwood & Sons and preferred them because they could withstand his robust playing and hammering while he was growing deaf.

While both the Viennese and English pianos made a louder piano possible, there was still a drawback—players (and composers) could not play notes in quick succession.

The French Innovation: Érard’s Double Escapement

Instruments became heavier—as makers sought to strengthen them—and they grew louder. However, there was still the problem of repeating notes quickly. Cristofori’s action served as the blueprint for piano makers, and many innovations were introduced.

Sebastian Érard stands out with his 1821 patent for the “double escapement.” His innovation meant the hammer could strike the string again before returning to its original position. The hammer was kept close to the strings and the escapement action was re-engaged and ready to play the next note.

American Pianos: The Age of Cast Iron

Today, we can thank Alpheus Babcock for the cast iron frame found in modern pianos. Babcock filed a patent for a full cast iron plate for a square piano in 1825. A cast iron frame took the tension off the wooden frame and a myriad of piano shapes and sizes started to emerge. Thicker wires could be used, and pianos became louder. The upright piano also entered the average house, and everyone could have a piano no matter what their space.

Until 1859 pianos were straight-strung—all the strings ran parallel to each other like a harpsichord’s strings do. However, Steinway & Sons produced the first overstrung grand piano in 1859. The low bass strings are angled over the middle strings meaning the piano has a richer tone.

The Modern Piano Has Arrived—Long Live the Piano!

Around 1870 the modern piano was born. Very little has changed since then regarding piano manufacturing and design.

The modern piano had arrived and along with it, the middle class. In 1909 around 365,000 pianos were sold compared to the few thousand sold in 1850. During the Industrial Revolution, factories and cast iron certainly played their part in giving music to everyone.

Grand pianos come with two (or three) pedals. Most commonly the left pedal shifts the keyboard to the right and the hammers only strike two of the three strings. This is known as the una corda pedal when harpsichords would only strike one of the pairs of strings. However, the trade-off is a change in timbre. The right pedal is the sustain pedal and lifts the dampers off the strings to allow the pianist to achieve smooth (legato) playing or allow the strings to vibrate freely. Larger pianos have a third pedal, known as the sostenuto pedal placed in the middle. When the pedal is used with the right timing the player can strike the keys and sustain the notes, but they can then “play over” those sustained notes without losing the sustained sound.

Since 1885, the piano has become standardized, and innovations are few and far between nowadays. Cristofori’s action was improved through the next two centuries, but the basics stayed the same.

Modern Innovations Worth Noting

Various piano manufacturers have produced some notable designs. Of course, there are some innovative composers too who wrote interesting music for the piano. Below are some select examples.

Pedal Pianos

Luigi Bargato patented the Doppio Borgato Model L282 pedal piano in 2000. The premise of a pedal piano is that a second piano is placed underneath the “main” piano and the pedals are similar to those of an organ. Any composition written for a pipe organ can also be played on the Borgato Doppio.

A Piano With Four Pedals

Fazioli, an Italian piano manufacturer, overcame the problem of the una corda or “soft pedal” by introducing a fourth pedal to the Model F308 pianos. Instead of shifting the keyboard and altering the timbre, the fourth pedal shifts the hammers upward. Reducing the striking distance allows the piano to produce a softer sound without compromising on the timbre.

Sympathetic Strings

Another innovation worth mentioning is the 1873 invention by Julius Blüthner’s aliquot string system. A fourth string is placed slightly above the three strings of the top three octaves, but the hammers do not strike it. However, it vibrates sympathetically and creates a richer tone.

Some Modern Playing Techniques

Henry Cowell (1897-1965) introduced extended piano playing techniques (techniques that fall outside the scope of tradition) and eschewed the use of the keyboard in works like The Banshee (1925) and the Aeolian Harp. The player would scrape, scratch, bang, or pluck the strings of the piano to produce sounds.

Other extended techniques Cowell used can be seen and heard in the composition, Three Irish Legends, where the performer uses their whole arm to create cluster chords.

John Cage, an avant-garde composer, had other ideas for the piano and once faced the challenge of insufficient space on the stage for percussion instruments. Ergo, he turned the piano into a percussion ensemble. The original idea of a prepared piano can be traced back to 1940 and the performance of the dance piece by Syvilla Fort called the Bacchanale. Cage also credits Henry Cowell with inspiring him to “prepare” the piano for performances.

Final Thoughts

The modern piano has undergone many developments to arrive at its final form. Each generation sought to improve on the previous one’s innovations, and it drove Western music forward. While the modern piano’s predecessors like the clavichord and harpsichord fell out of favor for some time, the historically informed performance movement offers a glimpse into the original composer’s world and soundscape.

Playing Beethoven on an 1816 Broadwood piano or Mozart on a fortepiano gives us a glimpse of what audiences would have heard. Each instrument has its place in the world of music. The piano may have undergone a long journey, but it is here to stay and fill the ears of listeners for many years to come.

Learning a musical instrument, like the piano, has many benefits like enhanced memory, improved mental health, and the sharpening of fine motor skills. So, why not treat yourself to the world of music? Remember, you do not have to become the next Beethoven or Mozart—you are doing this for yourself and your enjoyment.