The Papacy is arguably the longest continually running institution in history, and is less than a decade away from running for 2,000 years. This timeline assumes Peter was the first of a continuous line of popes running through the ages to Pope Leo XIV, elected on May 8, 2025. Surprisingly, the papal succession only became an official doctrine of the Church about 155 years ago, though it has been a long-held view since the 2nd century CE, and crystallized during the 4th to 5th centuries CE. Throughout this period, the Church has experienced many highs and lows, and gained and lost power.

Papal Succession

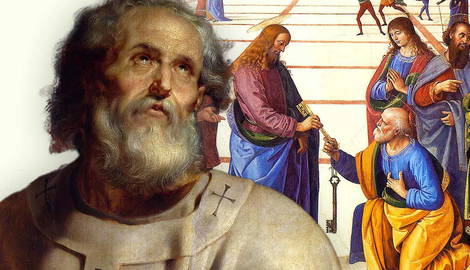

The Catholic position on papal succession rests on their interpretation of Matthew 16:18: “And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”

They believe these words of Jesus established Peter as the first pope. Because Peter died a martyr in Rome during the persecution under Nero around 64 to 67 CE, according to tradition, the city became the center of apostolic authority. That position of Peter as the apostle upon whom the Church was established has transferred to the bishop of Rome, and then on from one bishop to the next throughout the ages to the current pope, Leo XIV.

The view of Peter as the first in a continuous line of leaders of the Church residing in Rome is evident from writings by Church Fathers from the 2nd century. Historical evidence for his role as “pope” in the modern sense is sparse. Clement I and Ignatius of Antioch emphasized Rome’s growing authority in the early years of Christianity, but there was no centralized authority in Rome to speak of then. The modern papacy, with centralized authority, developed gradually from the 3rd century onward.

Initially, the local clergy and laity in Rome elected their bishop. As the influence and authority of the bishop of Rome grew, so did those who elected the pontiff. The emperors of the Western and later the Eastern Roman Empire influenced and approved papal elections from the 4th to the 7th centuries.

During the Frankish and Feudal Period of the 8th to 10th centuries, there was much political interference in the elections of popes. Pope Nicholas II established a College of Cardinals to elect the pope in 1059 CE. The Conclave System for papal elections was developed during the 13th century.

Many bishops from different cities used the title “pope,” which derives from the Latin word papa and means “father.” During the 11th century CE, it became exclusive to the bishop of Rome as a sign of his primacy over other bishops, though some of them, like those in Alexandria, used “pope” earlier. Papal succession and authority were defined as formal doctrine during the First Vatican Council held from 1869 to 1870 in the dogmatic constitution Pastor Aeternus.

Ebbs and Flows of the Papacy

In the early years of Christian history, the Church experienced intense persecution. During that time, the Church grew exponentially despite the slaughter of many Christians by the Romans who ruled the civilized world of the time. With the reign of Emperor Constantine, the situation changed drastically for Christians in the empire. The Edict of Milan legalized Christian practice in Roman-held territories, and soon after, the Edict of Thessalonica proclaimed Christianity the Roman State religion in 380 CE.

This change to the legal status of Christianity enhanced the status of the bishop of Rome. Pope Leo I of Rome, who reigned from 440 to 461 CE as the 45th pope in succession, asserted authority over other bishops. He engaged in political talks with invading powers, such as negotiating with Attila the Hun, though the papacy was not a significant political power yet. His legacy, however, earned him the title “Leo the Great.”

The Western Roman Empire fell soon after his reign, leaving a power vacuum in Italy when Germanic tribes took territories previously held by Rome. The population of Rome shrank to about 100,000 from more than a million at its peak. This decline influenced the Church until Pope Gregory I changed its fortunes and implemented reforms in Rome during his relatively short papacy from 590 to 604 CE. He brought spiritual reforms, played a greater diplomatic role in civil affairs, established charitable and social services, and provided the kind of leadership the city and greater society needed. He was instrumental in expanding the missionary work of the Church, like sending Augustine to convert the Anglo-Saxons. His papacy increased the spiritual and administrative influence and authority of the Church. Today, we know him as Gregory the Great due to his impact on the Church and society.

The High Middle Ages

The Papal authority, however, did not go unchallenged. The Investiture Controversy saw popes and monarchs clash about who had the right to appoint bishops. Pope Gregory VII asserted papal authority in the Dictatus Papae in 1075, which resulted in the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV, waiting barefoot in the snow for forgiveness from the Pope. The matter was not settled, though, and later conflicts between the papacy and monarchs ensued sporadically.

The Papacy reached the zenith of its power in the 13th century under Pope Innocent III, who reigned from 1198 to 1216. He freely interfered in European politics, launched the Fourth Crusade, and convened the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. He asserted papal supremacy over kings and emperors and standardized Church practices, displaying his civil and spiritual authority.

The papal prestige of Rome waned when French influence resulted in the Avignon Papacy. The Western Schism further weakened the Church and how people perceived its legitimacy and integrity while rival popes reigned in Avignon and Rome. The matter was settled during the Council of Constance (1414-1418), which saw unity restored as Martin V was elected as pope instead of the rival popes.

The Reformation to Modern Times

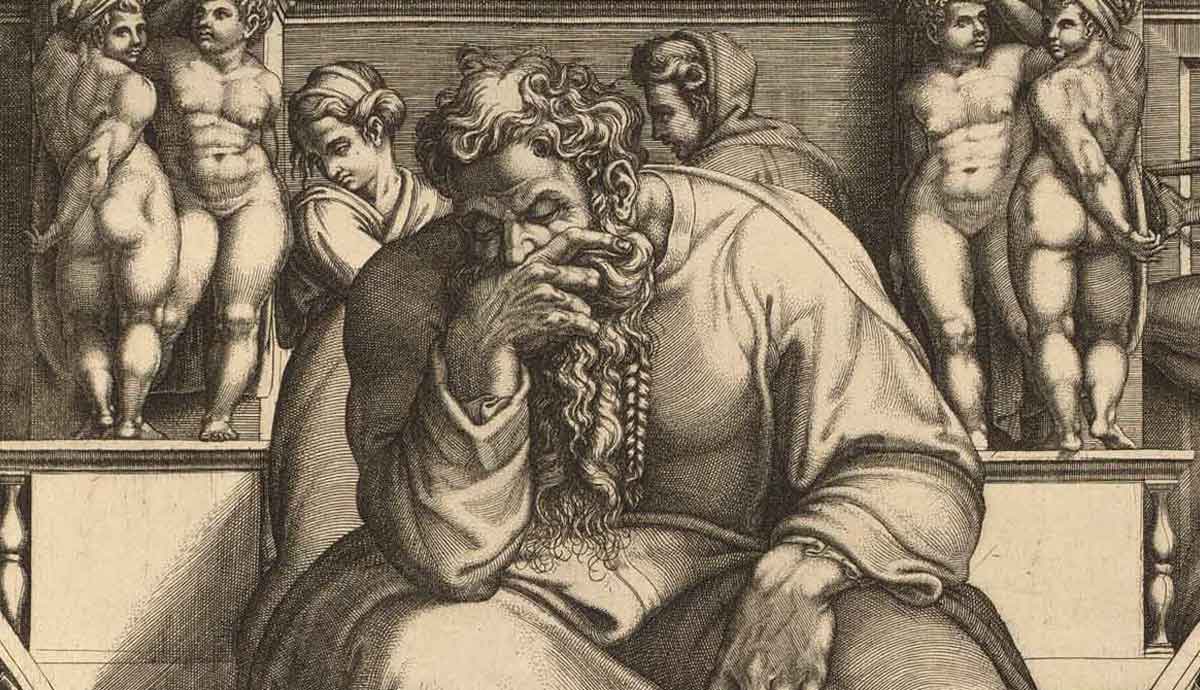

Barely a century later, the Reformation started, exposing the abuses and hypocrisy of the Church. At the time, the Church played a significant role in society and culture, patronizing artists like Michelangelo and Raphael to adorn their cathedrals and palaces with works of art and showcasing their riches and opulence. The spiritual decline in its ranks was laid bare, and the Church pushed back against Reformed narratives. The Jesuit order was instrumental in this process and missionary work that saw Catholicism spread globally.

The Enlightenment saw the Papacy lose much of its temporal power, and the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars weakened the Papal States. Eventually, the unification of Italy in 1870 saw the Papacy lose the Papal States, and Pope Pius IX considered himself a “prisoner of the Vatican.” Later, the Lateran Treaty established the Vatican City as an independent state in 1929.

The recognition of the Papacy as a significant player in international politics and ecclesiastical events is evident from the Second Vatican Council, Ecumenism, and Pope John Paul II’s role in bringing down the Soviet Union. The attendance of serving and previous American presidents at the funerals of Popes John Paul II and Francis shows the respect and regard they, and other world leaders who attended, had for them as spiritual and political leaders.

Papal Names as a Symbolic Style of Governance

For the first 500 years of Christian history, people called the popes by their given names. That practice gave way to choosing a papal name when Mercurius was elected Pope in 533 CE. He wanted to avoid any connotations people might make to the pagan deity. He chose the name John in honor of the first Pope John and Saint John. Since a previous pope had the name John, he became John II. The use of elected names was rare from the 6th to the 10th centuries, with most popes retaining their birth names. Those who did choose other names did so to honor popes or saints they admired.

The general practice of keeping given names changed in the 11th century with the election of German popes who often selected names of early church bishops to signify continuity. Choosing a new name symbolized a new mission or spiritual rebirth and signaled the direction and style of government the pope intended to follow. Some names featured prominently, like John (21 excluding antipopes), Benedict (16), or Pius (12). New popes avoided the name Peter out of respect for the first pope. It would be pretentious to name oneself after the pope appointed by Christ himself.

Some popes adopted the names of more than one saint, like Pope John Paul I and II. When Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio was elected pope, he was the first to name himself after Saint Francis of Assisi, thus reigning as Pope Francis. The name of the current pope, Leo XIV, indicates that he will likely work toward theological clarity and firmness, as well as establishing Church authority like his namesake Leo XIII did.