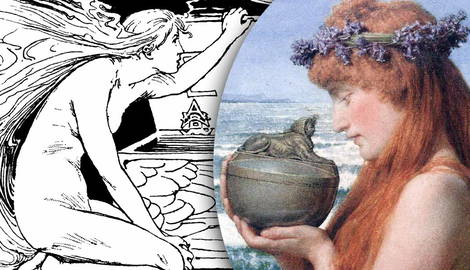

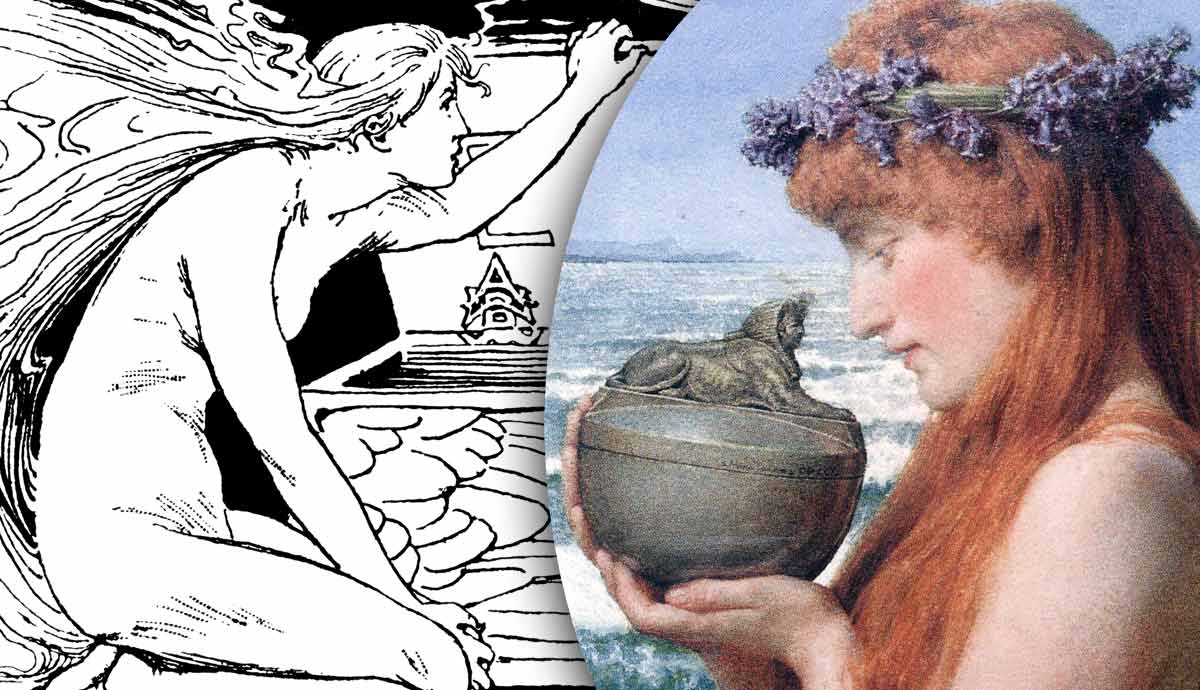

The story of Pandora’s box is a well-known tale about Pandora, the first woman according to ancient Greek mythology, and a box given to her by the gods. Recounted in Hesiod’s Theogony and Works and Days, the box was originally conceptualized as a jar, only becoming a box when a later author, Erasmus, translated the Greek word pithos as pyxis, the Latin word for box. The story serves as an explanation for why mankind must suffer all the hardships of life and why they must work to sustain themselves. As in the stories of many ancient cultures, such as that of Adam and Eve, original sin was caused by the destructive curiosity of a woman.

Elpis: The Spirit of Hope

Elpis was the embodiment of hope, much like how Nike was the embodiment of victory and Eris the embodiment of strife. There is no source that details who her parents were, but it was either Nyx, the primordial goddess of night, or Eris. Given her place within Pandora’s box with the rest of the evil spirits, who were all children of Eris, it’s not inconceivable to believe that she was one of her children.

The ancient Greek word elpis has commonly been translated to mean “hope,” though a more nuanced translation would be “supposition” or “expectation,” both in reference to hopes or fears. In this way, hope is neither a good thing nor a bad thing, but dependent on the situation and the effect it has on the person in possession of it.

The Story of Pandora’s Box

The best account of Pandora’s box comes from 7th-century BCE poet Hesiod in his Theogony, an epic poem about the birth of the gods detailing Zeus’ defeat of the Titans and rise to power. It also appears in his Works and Days, a didactic poem about man’s lot in life and how to live well.

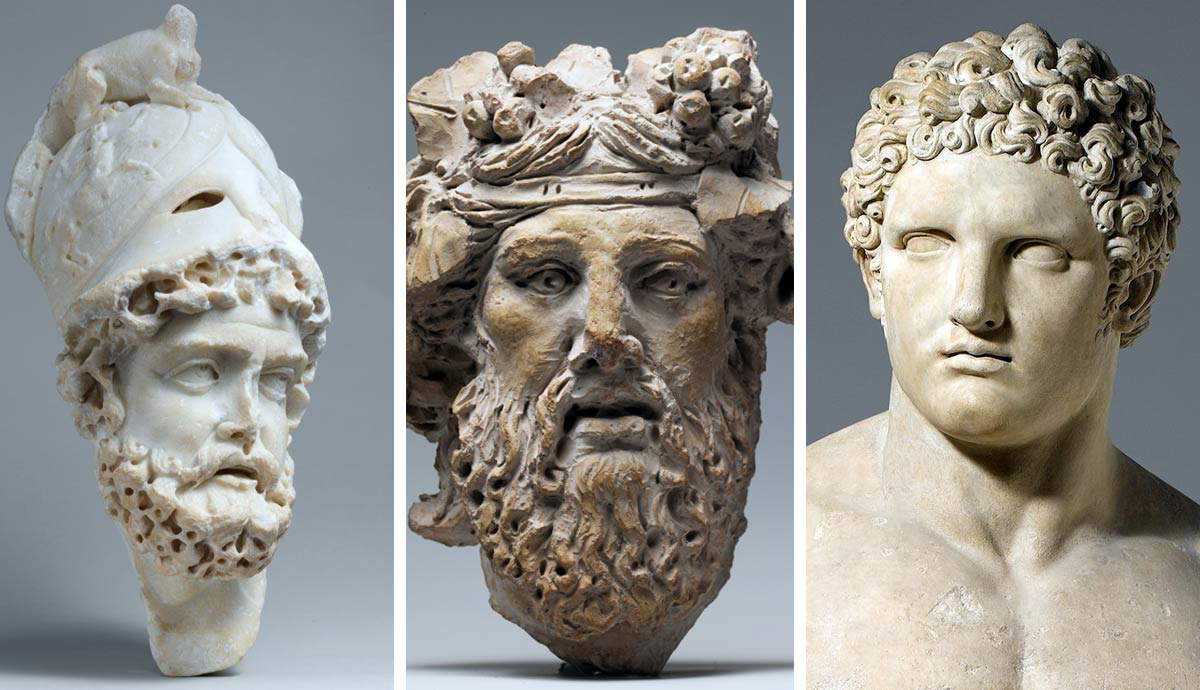

Pandora, her name meaning “giver of all gifts” or “she to whom all gave gifts,” was the first woman created as a punishment for mankind. Zeus had once hidden fire from mankind in order to punish them for a trick Prometheus played on him at Mekone, but Prometheus stole fire back in a fennel stalk. Annoyed that his punishment was negated, Zeus came up with another plan.

He had Hephaestus mold earth and water into the shape of a beautiful maiden, and give her human speech. Athena taught her skills and weaving, and Aphrodite instilled in her grace and passion. Hermes then placed in her a “canine” mind and a thieving nature. All the gods dressed her in finery and jewelry, and Hermes brought Pandora to be wed to Epimetheus, the brother of Prometheus.

Ignoring Prometheus’ advice to never accept a gift from Zeus, Epimetheus took Pandora into his home. Up until this point, men had lived easy lives without hardship or illness and never growing old, but then Pandora lifted the lid off a jar, spilling its contents and leaving humanity at the mercy of countless evils. Pandora then closed the lid of the jar before Hope was able to fly out.

The common reading of the story is that the jar contained all the evils of the world, and by opening the lid, Pandora released them, thus causing all the pain and suffering humans have to deal with in life. However, this presents a problem. If the jar contained evils, what was Hope doing inside it?

Hope in a Jar

It should be noted that in Hesiod’s account of the story, the contents of the jar are not specified. He simply wrote that Pandora spilled the jar’s contents, whatever they may be, leaving hope behind and mankind to deal with the evils of the world. The jar itself is never mentioned before this point, leading to the thought that he was working from an already established myth that would have been known to his audience.

It is possible that the jar was one of those mentioned in Homer’s Iliad, which were in Zeus’ possession. There it was written that Zeus had two jars from which he gave “gifts” to man, one full of evils and the other full of blessings. The question then arises, from which jar did Pandora lift the lid?

The common reading is that the jar contained evils. If this is the case, then why was Hope within the jar? Did Hesiod consider hope to be a detriment to humanity in the same manner as disease? This has been a consistent issue that scholars have tried to solve for years.

The symbolism of the jar is also scrutinized. In the story, the container is a pithos, a ceramic storage jar typically used for food. Yet it acts both as a prison for the evils, who are supposedly not among men at this time, and also as a storage container for Hope once the evils are released. The nature of the jar seems to conflict with itself.

There are a few schools of thought to solve this issue. Firstly, Elpis remained in the jar to preserve hope for man, or she remained in the jar to keep hope from man. This is also further divided depending on whether hope can be thought of as a good or an evil.

Starting with the common reading of the myth, that Hope was a good thing, and by remaining within the jar, was kept from man. This would mean that Hesiod believed the human condition was hopeless and generally desperate. It would also imply that man never had Hope, since the jar was acting as a prison for all things inside it.

The issue with this reading is that if Hope is good, why then did Zeus put it inside a jar of evils during a time when mankind lived in peace and abundance? And notably, a jar he seemingly intended to be spilled, since all things happen by the will of Zeus. If Hope was an evil, then why not allow it to be released with the others? If Hope was instead meant to have been preserved for humanity by remaining in the jar, then the implication is that even before the jar was spilled, humanity was subject to the evils within. This is directly contradicted by the text of the story in Works and Days.

This problem disappears if we consider that the jar Pandora opened never contained evils but instead blessings, and that the jar was not a prison. This would imply that the evils that afflict mankind were already present before the jar was spilled. This fits with Hesiod’s other body of work, the Theogony, where he wrote that evil spirits, such as suffering and disease, were primordial beings and separate from Zeus’ conflict against Prometheus and humans. Symbolically, this would mean that humanity was in possession of the tools with which to combat those primordial evils, and it was only at the spilling of the jar’s contents that we lost those tools, leaving only hope behind.

That also fits with stories written by later authors. The 6th century BCE poet, Theognis of Megara, wrote that Hope was the last goddess left among mankind, the others having fled back to Olympus. Babrius, a 3rd-century CE poet, elaborated on the story. He wrote that Zeus entrusted mankind with a jar containing blessings, but an unspecified man became curious about its contents and so opened the lid, letting all the blessings fly back to Olympus. A version by Macedonius made the one who opened the jar Pandora.

Hope can also be considered a spirit with dual natures, such as how Hesiod described Eris earlier in the poem. This reading would explain Zeus’ desire to keep hope inside the jar when all the other blessings flew out. If he was trying to punish humanity, it wouldn’t make much sense to leave them with a blessing, unless that blessing was a double-edged sword. Through much of the Works and Days, Hesiod makes clear his view that even strife can be a good thing when it drives a man to work rather than to conflict. The same can be true for Hope. It is good when it leads a man to work to achieve his expectations, but it is evil if it drives a man to idleness.

Why Did Pandora Open the Jar?

Pandora’s motivation for opening the box can be gleaned from Hesiod’s description of Pandora’s character and his treatment of women throughout the rest of the poem. He wrote that Pandora had a canine mind, deceptive language, and a thieving nature. The dog symbolism was generally used to denote greed and gluttony, as well as insolence and shamelessness. All these things depict Hesiod’s mythical archetype for a woman. Someone beautiful and bewitching, yet shameless and greedy.

Further hints to her motivation come from the two other women described in the poem, the bad wife and the woman who roots around in the granary. The bad wife is gluttonous and unindustrious, one who doesn’t contribute to the prosperity of the household and is instead a burden on her husband. The second woman is more directly linked with Pandora in that she is explicitly a thief and uses deceptive language to root around in the storage area. All these points lead to the conclusion that Pandora opened the jar in order to steal whatever was inside.

Pandora as Earth Goddess

Pandora was thought to have originally been an earth goddess whom Hesiod adapted to his poem. This can be seen in her imagery, where she was depicted crowned and veiled and rising from the earth. The imagery of the pithos, itself an earthenware jar used for food storage, could also be a metaphor for the earth. It is the vessel that holds all things needed for humanity to live and thrive. Hope being the only blessing remaining in the jar symbolizes man’s hope that those lost blessings still reside in the earth, but it is only through labor and suffering that he is able to realize it. Through Pandora, women are connected with the earth and man’s relationship with it.

In a poem that extols the virtue of self-sufficiency, the paradox is that man’s dependency on the earth and on women is required for it. Without women, a man will have no heirs and no one to take for him when he’s old, but she also poses an economic burden, requiring him to work not just for himself but for her as well. These things are inescapable facts of life for the Iron Age man, who was the implied audience for the story. The only thing left to him was Hope. Hope that his fields produce, Hope that he has a good wife who gives him good children, and Hope that his efforts are enough to realize those things.

The myth of Pandora is more than a warning against reckless curiosity; it’s a nuanced reflection on the human condition. Hesiod’s ambiguous treatment of Hope invites us to view it not as a universal good, but as something to approach with caution. Like his portrayal of women, Hope holds the power both to sustain and to deceive. That is the paradox of life: the things we depend on most are often those most capable of doing us harm.

Selected Bibliography

Beall, E. F. (1989) “The Contents of Hesiod’s Pandora Jar: Erga 94-98,” Hermes, 117(2), 227–230.

Canevaro, L. G. (2013) “The Clash of the Sexes in Hesiod’s ‘Works and Days,’” Greece & Rome, 60(2), 185–202.

Hesiod (7th century BCE) Theogony and Works and Days, translation by D. Wender, Penguin Group, 1973.

Marquardt, P. A. (1982) “Hesiod’s Ambiguous View of Woman,” Classical Philology, 77(4), 283–291.

Verdenius, W. J. (1971) “A “Hopeless” Line in Hesiod: ‘Works and Days’ 96,” Mnemosyne, 24(3), 225–231.

Wolkow, B. M. (2007) “The Mind of a Bitch: Pandora’s Motive and Intent in the Erga,” Hermes, 135(3), 247–262.