Horyu-ji, located in modern-day Nara Prefecture, is one of Japan’s most venerated temples. Its origins trace back to the mid-Asuka Period (538–710) when Buddhism was beginning to thrive in the country. The world has changed greatly since then, but Horyu-ji has mostly remained the same, and today is home to some of the oldest wooden structures in the world. For this and other reasons, it was registered as the first UNESCO World Heritage Site in Japan. Here is everything you need to know about Japan’s oldest temple.

A Place of Recovery and Rebirth

According to records preserved in the temple and early Japanese chronicles, the catalyst for the creation of Horyu-ji was Emperor Yomei (540–587). Gravely ill, the emperor ordered the construction of a temple dedicated to the healing “Medicine Buddha” (Yakushi Nyorai/Bhaisajyaguru) sometime in the 580s in order to aid in his recovery. Although he did not live long enough to see the project completed, his son, the semi-mythical Prince Shotoku—who over the centuries grew a cult-like following around himself because of his deep devotion to Buddhism—realized his father’s vision. With his help and that of his mother, Empress Suiko, Horyu-ji, then known as Ikaruga Temple, was completed in 607.

However, the entire temple was destroyed in a fire in 670 (sadly common with Buddhist temples). The Nihon Shoki, the second-oldest Japanese chronicle, states clearly that “Not a single building was left” (Aston, p. 293). The entire complex had to be rebuilt from scratch between 708 and 714. For the longest time, that has been the accepted timeline, but as early as the 20th century, there have been dissenting voices questioning the extent of Ikaruga Temple’s destruction. It is now accepted that the central pillar of the temple’s Five-Story Pagoda (Goju-no-To), was made from a cypress that was cut down in 594. It seems improbable that the Horyu-ji reconstruction would use a random century-old pillar with no connection to Ikaruga whatsoever, meaning that some parts of it had to survive.

Designing Transcendence

Horyu-ji is made up of the Western Precinct (Saiin Garan) and the Eastern Precinct (Toin Garan) housing the Five-Story Pagoda, the Kondo Main Hall (“the world’s oldest extant wooden structure”), and other buildings all laid out in an asymmetrical design. The complex is accessible via the Chumon Middle Gate, the threshold to the sacred interior of Horyu-ji guarded by fearsome Nio guardian statues. As you pass through it, you enter a courtyard surrounded by the Kairo Covered Corridor (a cloister) with the Daikodo Great Lecture Hall across from the Chumon but not aligning perfectly with it. A short distance from the gate, but notably not in the center of the courtyard, there is the pagoda to the left and the Main Hall to the right.

This departure from axial symmetry typical of Chinese temples has been interpreted by some scholars as an early attempt at a distinctively Japanese architectural style. While it is possible that Horyu-ji’s layout reproduces a lesser-known, now-lost trend once found in mainland Asian Buddhist temples, it is equally likely that the irregularity and a purposeful abandonment of pursuing perfection has been partially inspired by the design of Shinto shrines.

An interesting detail is the Kairo whose pillars exhibit a subtle bulging known in classic architecture as entasis, an element reminiscent of ancient Greek buildings. This has actually led earlier researchers to speculate about a possible Hellenistic influence on Horyu-ji via Gandhara (modern-day northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan). However, the scholarly consensus today is that the similarities between Horyu-ji and ancient Greek architecture is little more than an interesting coincidence and further proof of the temple’s indigenous design, as entasis is not found in historic Buddhist temples in China or Korea.

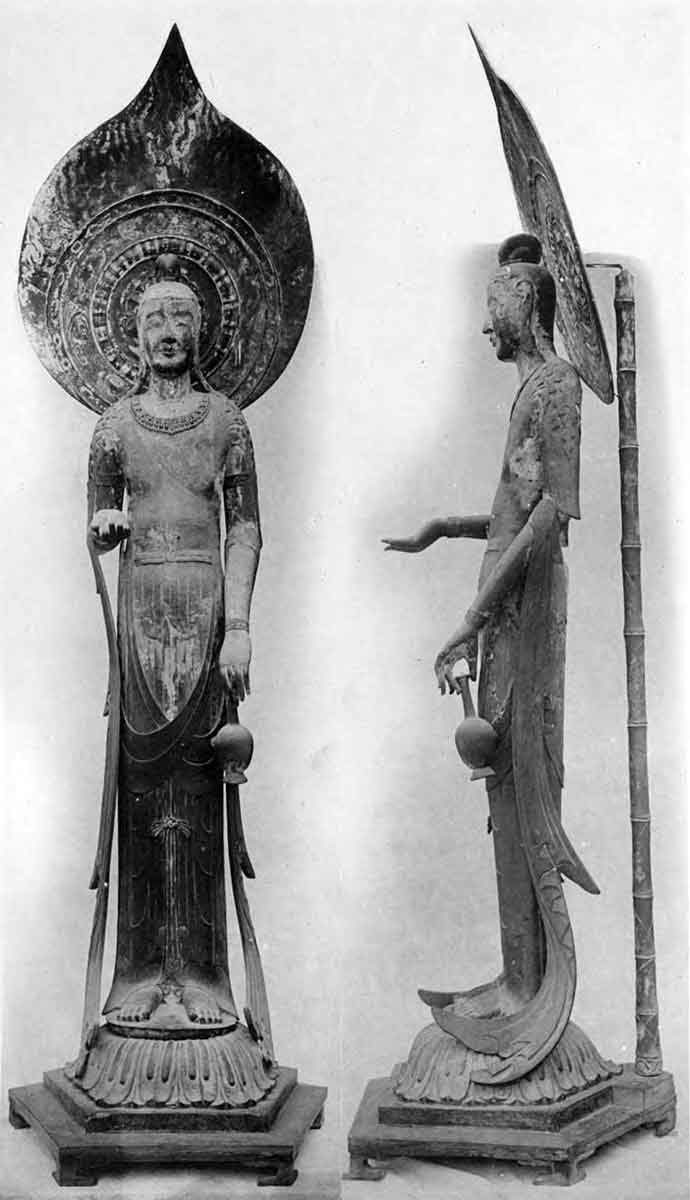

Other structures within the complex include the Shoro Bell Tower, the Kyozo Sutra Repository, and the octagonal Yumedono Hall of Dreams that forms the center of the Eastern Precinct (with the Western one focusing around the pagoda and Main Hall) and which was constructed on the former site of Prince Shotoku’s private residence. The name of the hall comes from a legend involving the prince seeing a golden Buddha in his dreams, who tasked him with spreading Buddhism all throughout Japan. The dream has been immortalized in the form of Kuse Kannon, a gilded camphorwood statue that the temple only unveils two times a year.

A Repository of Buddhist Beauty

Besides being an architectural marvel, Horyu-ji is also home to over 2,300 historically significant Buddhist artifacts. Among them, nearly 190 have been designated as National Treasures or Important Cultural Properties of Japan. The Main Hall contains some interesting examples of Buddhist art like a collection of statues representing various Buddhist figures, including that of Shakyamuni (also known as Gautama), the historical Buddha, whose visage was most likely based on the likeness of Prince Shotoku. But the majority of the temple treasures are housed in the Great Treasure Gallery.

Constructed in 1998, the gallery now houses such masterpieces as Kudara Kannon, a 2.1-meter-tall statue of the goddess of compassion and mercy carved from a single camphor trunk. Despite its name referencing the ancient Korean kingdom of Baekje, scholars believe that the statue was produced in Japan. Another standout is the Tamamushi Shrine, a seventh-century miniature altar adorned with intricate Buddhist imagery, which might have originally belonged to Empress Suiko. Also of note is the statue of the “Dream-Changer” Yumechigai Kannon, believed to have the power to transform nightmares into peaceful dreams, and the Lady Tachibana Shrine, featuring a delicate bronze Amida triad with notable Tang Dynasty influences.

Among the most historically significant and stunning treasures of Horyu-ji are the One Million Pagodas, a set of miniature wooden towers commissioned by Empress Koken in the 8th century. Each houses a printed Buddhist charm and acts as a talisman in order to bring peace to the land. The pagodas were originally distributed among the 10 major temples of Nara, with each one receiving 100,000 miniatures. Horyu-ji is the only temple that has retained a significant number of them, today housing over 46,000 tiny pagodas.

Secrets of the Five-Story Pagoda

Of all the structures within Horyu-ji, the Five-Story Pagoda is perhaps the most iconic. It is also the most sophisticated. Measuring approximately 32.5 meters in height, it is widely regarded as the oldest wooden pagoda in Japan and one of the oldest wooden towers on the planet. Inspired by Indian stupas, it was constructed to enshrine relics of the historical Buddha and ashes of important devotees that are believed to rest around three meters beneath its base.

One of the most fascinating things about the pagoda is its structural ingenuity that makes it resilient against earthquakes and typhoons, two natural disasters unfortunately common in Japan. The key to the pagoda’s long life is the shinbashira, the aforementioned 6th-century pillar made from cypress that runs vertically throughout the tower.

The flexible monopole skeleton of the Goju-no-To effectively acts as a quake dampener, absorbing seismic energy and making the pagoda sway when the ground moves, thus keeping it standing upright for the last 1,300 years. The tower’s architecture also employs traditional Japanese joinery techniques, which, because they do not use nails, allow the components of the pagoda to shift during earthquakes, dissipating the seismic energy to prevent a catastrophic collapse. The pagoda’s survival across centuries of war and disasters is a true testament to the superb skills of its builders.

Atop the pagoda you will find a spire called a sorin made up of many elements such as rings, a flame-shaped ornament known as suien (“water smoke”), so called to protect against the destructive power of fire through word magic, and a hoshu (or hoju) jewel meant to symbolize dreams coming true. In Buddhism, that means achieving nirvana, which creates an allegorical representation of Buddhism itself with the symbol of enlightenment being placed high above the ashes of the faithful under the tower, emphasizing the heights that humans should strive for in life.

Further enhancing the pagoda’s spiritual and artistic heritage is the series of clay tableaux at its base. Dating back to 711, these dioramas depict significant episodes from the life of the Buddha. With 97 intricately crafted figures, these scenes provide a visual insight into the tenets of the Buddhist religion (or philosophy) without which Horyu-ji temple would never have existed.

Sources:

Translated by Aston, W. G. (2008). Nihongi Volume II – Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697.