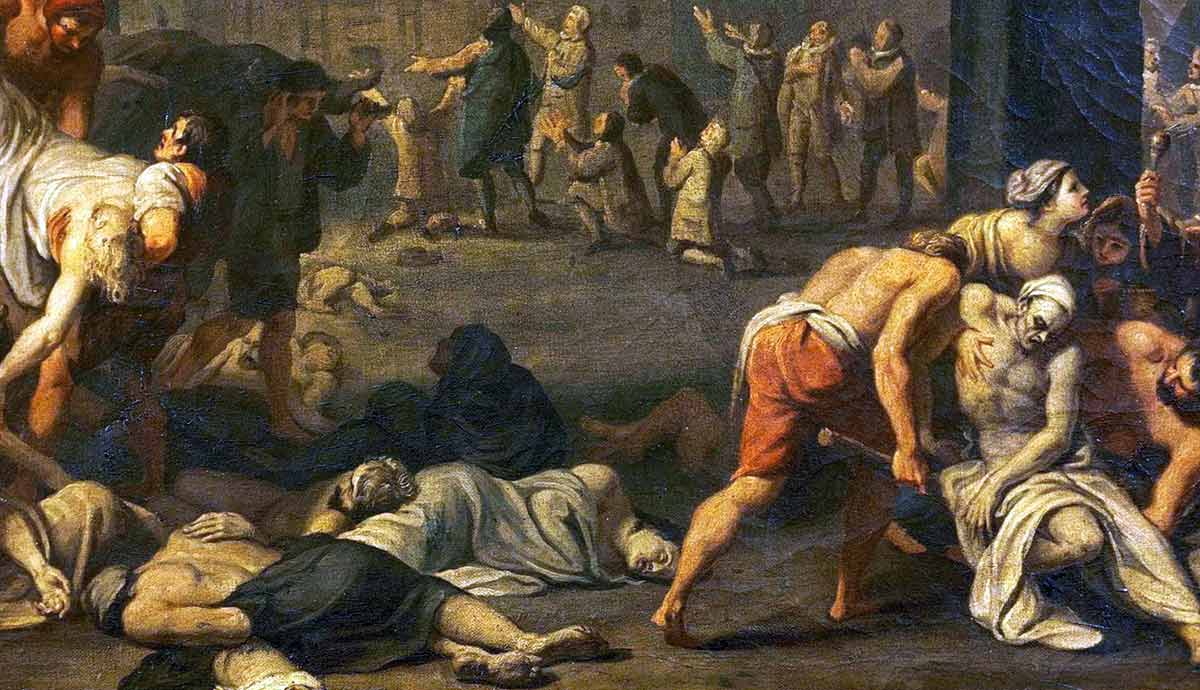

Arriving in Europe in 1347 and spreading across the continent, the Black Death had a significant long-term impact on social transformation. It created a labor shortage that empowered laborers and challenged the feudal order. In the post-plague years, it gave workers newfound freedom and bargaining power.

By 1349, the ruling classes had responded with new legislation that sought to control wages and establish harsh penalties for peasants leaving their manors for better pay. The elite’s reaction to the upheaval created widespread resentment, and by the late 14th century, it was clear the ruling classes would use all necessary means, including legal and violent force to maintain their dominance.

The Plague’s Impact on Wages

Before the plague, Europe’s large population kept labor cheap, but this reality was inverted almost overnight after the emergence of the plague. This was because the malady led to an era of labor scarcity that made workers more valuable. While the situation granted them leverage, it also led to social friction. In the immediate aftermath, the English chronicler Henry Knighton noted the change.

He observed that laborers now became insolent, and defied their lords’ commands. Historical data confirms that in the 1350s, the wage spike averaged 12 to 28 percent and showed further increases in the cities. Some manors experienced an over 60 percent increase in wages. By the 1360s, wages had risen by another 20 to 40 percent across England.

Laws Enacted to Rein in Runaway Wages

Responding swiftly and decisively to the fast evolving situation, King Edward III issued an Ordinance in 1349, followed later by Parliament passing a more detailed act in 1351 that began a formal legal suppression. It froze wages to pre-plague levels and forbade employers from offering more. In the following years, the Crown empowered sheriffs to enforce the laws often capturing and returning any fugitive laborers to their manors.

In 1351, the Statute of Labourers codified the system which limited workers to their local villages. The establishment of special commissions ensured initial enforcement, and by the 1350s, thousands of prosecutions were recorded against both workers and employers.

How Dress Codes Were Regulated

Born of the elite’s anxiety and widely flouted by desperate landowners, the wage laws failed to stop rising pay, but their failure created profound anxiety. The ruling class instead began policing social status, regulating the dress code of commoners and determining the fabrics they could wear. It, for example, forbade silk and silver for commoners.

In 1363, the English Parliament passed a sweeping statute that dictated what different social classes could wear but its main purpose was to make social rank visible. It attempted to reinforce the social hierarchy from the fields to the royal court, as the elite’s focus shifted to preventing commoners from dressing above their social status.

How Suppression Sparked Open Rebellion

Fueled by deep-seated resentment, legislative suppression periodically exploded into rebellion. But these uprisings varied in scale. They involved open social conflict that saw peasants attack castles and attack nobles. In the late 14th century, the revolts grew more organized and ambitious, with the English Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 marching on London. Inspired by the teachings of the radical preacher John Ball, and led by the military captain Wat Tyler, the rebels spread messages that proclaimed that God never wanted a few men to feast while most went hungry.

Thousands of ordinary farmers and craftsmen were inspired and marched to London. They burned the homes of the king’s advisors and forced the young King Richard II to ride out and meet them. For one brief moment, the poor stood taller than they ever had.

The French Jacquerie of 1358 provides another brutal example of the uprisings, while in a separate event, disenfranchised Ciompi wool workers in Italy briefly restructured the government of Florence in 1378, winning political rights and guild recognition that lasted for over three years.

Long-Term Consequences

Led by figures like Wat Tyler, the English revolt at first seemed successful, but it collapsed after its leader was killed. The Crown soon carried out mass executions to reassert royal authority. After 1381, the revolt yielded lasting consequences and its greatest accomplishment was the gradual decline of serfdom. It forced the ruling class to abandon poll tax and hastened the end of institutional serfdom. The situation also created a new reality where the balance of power between lord and laborer was altered permanently.