The common modern perception of Vikings is that of lawless raiders, yet this could not be further from the truth. While they did raid, and their lifestyles often tended towards the more brutal side of human existence, they certainly had a strong connection to rules that needed to be obeyed.

The Viking world was surprisingly democratic in its legal structure, and it did not fade away after the Viking Era. Rather, it was absorbed into the structures of Europe. Much of it evolved and can still be seen today, while the ethos of civil participation that they brought is highly relevant in the history of democracy.

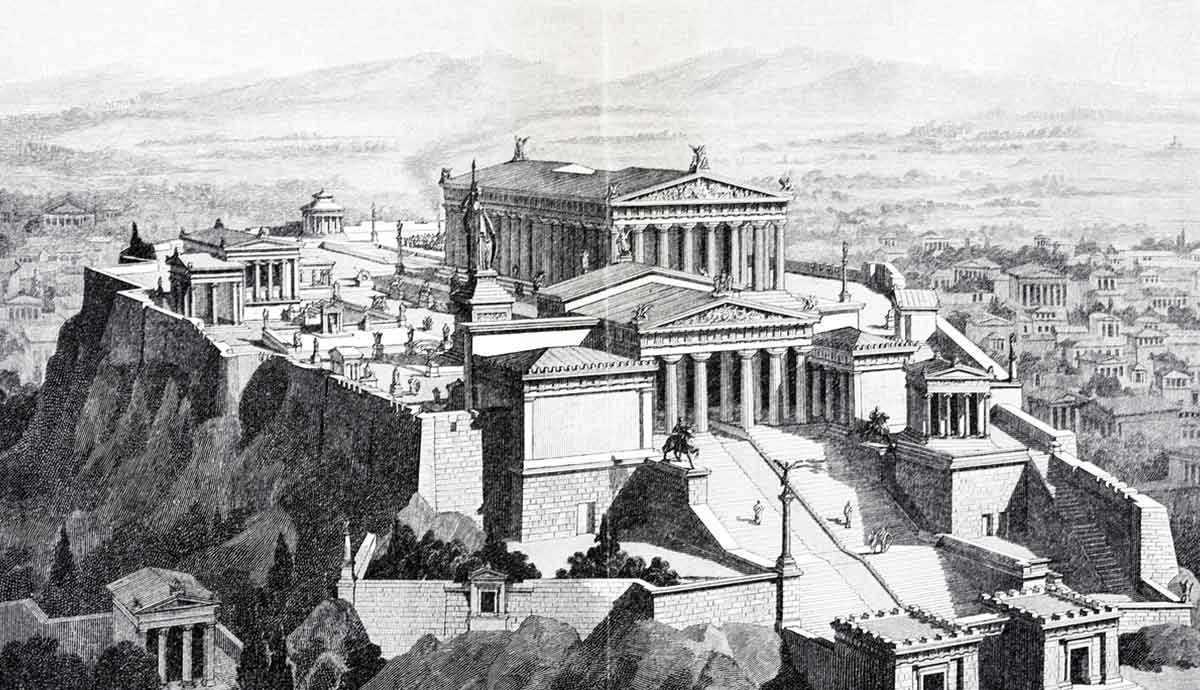

Greece AND Scandinavia: The Birthplaces of Democracy?

Greece is often quoted as being the birthplace of democracy. Modern democracy, in reality, has a nuanced evolution that extends far outside of Greece and the Classical Era, and includes influence from the Viking world.

In Greece, democracy originated around the 6th and 5th centuries BCE. The philosophy behind Athenian democracy was that citizens should have direct control over and participate in their own government. It is widely regarded in hindsight as being progressive for the time, yet it had significant drawbacks and challenges. Democracy, as practiced in Greece, was only open to adult male citizens. Women and slaves could not take part. It was also direct rather than representative. Direct democracy can lead to abuses by the majority, while minorities end up with little protection. It also allows for those with little expertise to make big decisions, while complex issues are simplified to “yes” or “no” choices.

Nevertheless, it was a foundation for a more inclusive society where the general population and their opinions were considered valuable.

The Vikings, in contrast, had monarchies. Their societal structure was, however, influenced by certain practices, with councils and juries, which could be considered democratic in retrospect. While the Greek model had philosophical underpinnings, the Viking systems were driven by pragmatic needs and were not designed to emulate any particular philosophy of governance. Nevertheless, the Vikings had notable cultural influence over many parts of Europe, and so too did their forms of governance.

Democracy: A Viking Thing

Central to governance in Germanic society, and particularly in this case, Viking society, was the “thing.” Also referred to as a folkmoot, the thing was a general assembly made up of free men, and it performed legislative functions, presided over by a lawspeaker. The thing was responsible for electing royal nominees and resolving legal disputes. It also served as a social forum where people could forge alliances, conduct trade, and organize marriages.

Like in Greece, the democratic process was heavily androcentric. Women could not vote, serve on juries, or hold any political office. However, their voices were heard, and in some rare cases in Viking society, women with particularly high prestige could be elevated to a decision-making council. The thing was responsible for settling disputes in a neutral fashion rather than leaving the matter to be resolved (or exacerbated) through bloodshed.

In contrast, the feudal system in much of the rest of Europe, and especially in England and France, was hierarchical, and all decision-making was done by the nobility. The peasantry had virtually no say in matters.

The importance of the “lawspeaker” in Viking societies was key. In a society with no written laws, it was the lawspeaker’s function to memorize laws and apply them to whatever context arose. This dynamic shifted in the 10th century when legal codes, recited by the lawspeaker, underwent the gradual process of being transcribed. Nevertheless, the duties of the lawspeaker as a repository for the law were still preserved out of tradition, and the lawspeaker commanded considerable respect.

Justice, in Viking society, was considered a duty of the entire community, and thus the process was a communal affair. Through debate and consensus, legal issues were resolved. This dynamic existed from the local level to the regional things, where decisions were made that affected entire nations.

The Viking (or Dane) Legacy in England

The Vikings had a significant impact on the fabric of England, where they were often referred to as “Danes.” From the sacking of the monastery of Lyndisfarne in 793 CE to the end of the Viking Era in England in 1066, their culture, language, forms of governance, and legal codes intertwined with Anglo-Saxon England in a way that left a lasting legacy.

In 865, the Vikings invaded England with the Great Heathen Army and began carving out kingdoms, defeating Northumbria, East Anglia, and half of Mercia. In May 878, King Alfred of Wessex defeated the Vikings at Edington, and the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum that followed established a boundary between the Viking and Anglo-Saxon parts of England. About half of England became known as the Danelaw, where Viking customs, governance, and legal policies were enforced. The word “law,” in fact, comes from the Vikings. In addition, the Vikings provided the foundation for the jury system, which was later refined by other influences, specifically the Normans, who conquered England in 1066 and who formalized many legal practices.

The Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum provided a foundational framework for the shared legal system that developed between the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings in the years that followed. Under King Cnut (r. 1016 to 1035), a Dane who ruled all of England, a unified system was put in place that was applicable throughout the entire realm. These laws represented a fusion of Dane and Anglo-Saxon law rather than a simple co-existence. Of note is the fact that the fusion of these systems was facilitated by shared cultural heritage. Similar concepts of legal procedure had evolved due to the common Germanic ancestry of the Anglo-Saxons and the Vikings.

Regions under the Danelaw can be said to have preserved a facet of democracy in the form of “sokemen,” who were people between free tenants and bond tenants. In other words, people in the Danelaw areas generally had more freedom and political autonomy. Even after the Norman conquest and imposition of feudalism, this dynamic persisted to some extent.

An Enduring Legacy in Iceland and the North

Largely free from major influences of other cultures for most of its existence, it is unsurprising that one of the most enduring examples of Viking governance is Iceland. This island, once free of human habitation (except for a few Irish monks), was colonized by Vikings beginning in the second half of the 9th century. In fact, Iceland’s parliament, the Althing, was founded in 930 CE and is often referenced as the oldest surviving parliament in the world. For more than three centuries after its founding, the Althing served as the general assembly where Iceland’s leaders met to discuss issues of great importance and to create laws and dispense justice.

The meeting of the Althing was the biggest event of the year in Iceland, and people gathered from all over the island to take part. Here, free men could have their voices heard, disputes could be settled, and other social activities could take place. As per tradition in other Viking cultures, the lawspeaker took a central role in conducting the proceedings.

While the position of lawspeaker no longer exists, there are many vestiges of the old ways that are still apparent in Iceland’s democracy. The parliament is still called the “Althing,” and although it was dissolved in 1800 and reestablished in 1843, the modern Althing still fulfills the same function, albeit with different methods. It is no longer simply an assembly, but a fully functioning modern parliament, and the original judicial roles have been absorbed into Iceland’s legal system. Nevertheless, it has symbolic significance as a democratic institution that predates the advent of modern democracy by some considerable time.

Unlike other European countries, Iceland didn’t have its own monarchy. It was established as a commonwealth, and it existed as a proto-democracy for the first three centuries before being ruled by Norway and then Denmark. It became an independent democracy after leaving its union with Denmark in 1944. Given this history, it is unsurprising that Iceland consistently ranks as one of the world’s most democratic countries, as the tradition is kept very much alive by its citizens.

It is also unsurprising that other Scandinavian countries and territories also rank highly in this regard. Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and the Faroe Islands all represent this dynamic to some degree, and all were almost exclusively inhabited by the Vikings.

The Evolution of the Thing Through Feudalism

Of note is the fact that feudalism never took hold in Scandinavia the same way as it did in the rest of Europe, with the exception of Denmark, which was geographically closer to the influence of neighboring feudal states. Nevertheless, Denmark still had a considerably high proportion of freemen. In Denmark, the things were gradually dissolved and replaced with the power of an absolute monarchy.

While feudalism was rigid and hierarchical in nature and based on hereditary inheritance, Sweden, for example, was barely a good example of this. Serfdom did not exist, and nobles had no hereditary fiefs. In Norway and Sweden, the things were never formally dissolved. In Sweden, they evolved into the Riksdag, first held in 1435, which functioned as a parliament. It was made up of four estates: Nobility, Clergy, Burghers, and, surprisingly, the Peasants. This was in stark contrast to the feudal systems in the rest of Europe, where peasants had very little representation, if any at all. The inclusion of the peasantry at the first meeting is a contested point, however, and they may have been represented only in subsequent meetings.

In Norway, the things were never fully dissolved, but they lost power to the monarchy. Their legacy was recognized in the name of the Storting (Great Thing), the new parliament that was established in 1814, and continues to this day.

While the thing is an obvious and conspicuous function of Viking “democracy,” it is not the legacy Vikings left behind. Rather, it was a symptom of the legacy. The most enduring legacy of Viking democracy lies not in any particular invented system but in a certain culture of governance that champions communal responsibility and seeks consensus through the individual’s investment in the system. To this day, this culture has persisted and has evolved in the countries where the Vikings had a significant cultural influence.