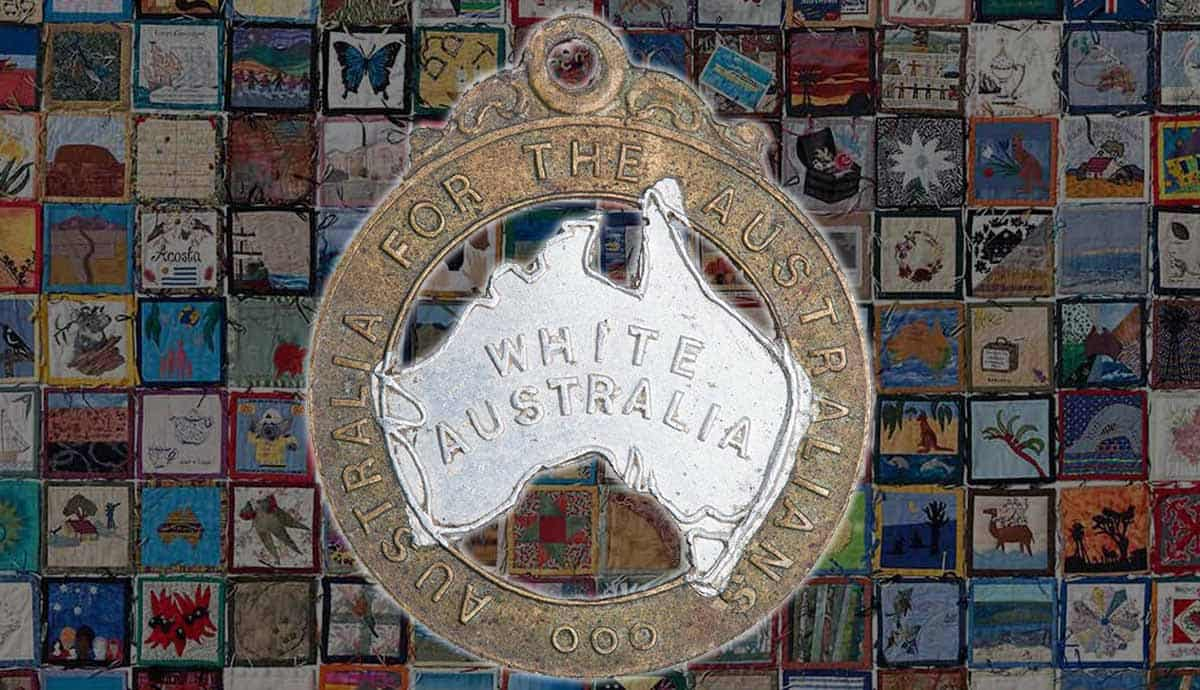

The Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 formally established the “white Australia policy” as a cornerstone of Australian society, linking Australian identity to whiteness. By restricting non-British migration to Australia, it deliberately shaped Australia’s demographic composition to create a homogeneously white society founded on British values. For more than five decades, non-white and non-British immigrants, along with seasonal workers such as miners and pearl divers, faced systematic exclusion, marginalization, prejudice, and increasingly strict immigration policies. The dismantling of the White Australia Policy in the 1970s contributed to the development of the multicultural society that Australia is known for today.

The Immigration Restriction Act

For more than five decades, the Immigration Restriction Act served the Commonwealth of Australia’s fundamental government policy and the cornerstone of the so-called white Australia policy. It came into law on December 23, 1901, and was one of the first laws passed by the new Commonwealth Parliament. It was part of a broader set of laws introduced in 1901 aimed at limiting and, if possible, eliminating immigration from China, Korea, and the South Sea Islands (South Sea Islanders were formerly referred to as Kanakas), as well as Japan.

In contrast, the Act encouraged immigration from European countries with predominantly British values. As a result, the Immigration Restriction Act played a significant role in developing and establishing a racially insulated white, European-based society, a society whose stability was perceived to depend on the exclusion of non-white individuals.

The law defined a prohibited immigrant, that is, an immigrant who would not be allowed into Australia, as “any person who when asked to do so by an officer fails to write out at dictation and sign in the presence of the officer a passage of fifty words in length in a European language directed by the officer.” In other words, the Act required that every non-white, non-European immigrant undertake a dictation test in a European language, at the officer’s discretion.

Similar Dictation Tests had already been implemented in Tasmania, New South Wales, and Western Australia in the late 1890s. After 1905, the test could be administered in any prescribed language. According to the Museum of Australian Democracy, the “Dictation Test was administered 805 times in 1902-03 with 46 people passing and 554 times in 1904-09 with only six people successful. After 1909 no person passed the Dictation Test and people who failed were refused entry or deported.”

Whiteness and British Values

The passage of the Immigration Restriction Act marked the culmination of years of what, by today’s standards, would be considered a series of racist measures aimed at curbing non-white immigration. The Chinese, much like Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, were seen as outsiders, as an obstacle to economic development, particularly in the Northern Territories. Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer (1860-1929), the appointed Special Commissioner and Chief Protector of Aborigines in the Northern Territory since 1912, imposed restrictions on Chinese and Asian workers based on his own personal class hierarchy.

As Russell McGregor notes in his book Imagined Destinies, “… at the bottom of the scale were the Aboriginals, the objects of protection, on whom there was no question that regulation and control should be strict and comprehensive.” Spencer once declared that, while Aboriginal people needed protection, in Darwin, “the Chinese are a great curse here,” because “they get hold of the natives and give them opium and sundry vile concoctions that they call whiskey.”

According to Spencer, both Aboriginal people and Chinese immigrants shared a tendency toward moral decay and depravity. He believed that, unlike Europeans or Australians of European descent, they lacked moral values and therefore constituted a “curse” that threatened to corrupt white Australia. His ideas were paternalistic and racist but they were widely accepted by thousands of people in early 20th century Australia.

The Immigration Restriction Act was not unique within the political landscape of the Australian colonies. Long before the creation of the Commonwealth of Australia on January 1, 1901, the colonies had enacted a series of restrictive laws as early as the 1860s to limit Chinese immigration, and later, following the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95, to restrict Japanese and South Asian immigrants as well.

The Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 paved the way for additional legislation aimed at creating opportunities solely for white immigrants. The infamous Pacific Islander Labourers Act, for instance, sought to restrict South Sea Pacific Islanders, who were either denied entry except with a license or deported if found on Australian soil after December 31, 1906. Section 16(1) of the Post and Telegraph Act mandated the hiring of exclusively white workers to transport mail to and from Australia. Two years later, the Parliament passed the Naturalization Act 1903, which has since been repealed, preventing non-European immigrants from becoming naturalized British subjects.

Miners and Pearl Divers

In a campaign speech delivered in 1903, Alfred Deakin (1856-1919), who would become Australia’s second Prime Minister that same year, declared that due to the Immigration Restriction Act and the Dictation Test, of the 31,000 individuals who entered Australia that year, 28,000 were Europeans. He noted, “… of the remainder, many of the colored persons came to Australia to engage on pearling vessels. The arrangement we have made is that they land only to sign their articles. A guarantee is taken from those who bring them that, when their time is up, they shall leave the country. By this means they never really enter Australia. They merely fish in our waters or just outside them.”

The white Australia policy was a direct response to widespread concerns that Asian laborers were “stealing” employment opportunities from white Australians, therefore undermining the stability of “white” Australia. This feeling was particularly influenced by the widespread anti-Chinese sentiment among European miners during the Gold Rush.

In the mid-1850s, the Gold Rush marked a new era in Australian history, politics, and demographics. Starting in 1851, European workers flocked to Australia, followed closely by a notable wave of Chinese immigrants. Between the 1850s and 1860s, approximately 40,000 Chinese workers from Southern China migrated to Australia, to Sydney and Melbourne, via Hong Kong. The majority of these migrants were men, and by 1861, they constituted 3.3% of the total population.

Over the years that followed, many Asian migrants relocated from the remote goldfields to rapidly developing cities like Sydney, Adelaide, and Melbourne. At the same time, underpaid South Sea Islanders were extensively employed on sugarcane plantations in Queensland, many of whom had been forcibly taken from their homes in the Pacific—a practice known as “blackbirding.”

Meanwhile, the pearling industry in northern Australia was flourishing thanks to the hard work of Aboriginal divers and Asian immigrants. In places such as Broome, Western Australia, Darwin, Northern Territory, and Thursday Island, Queensland, thousands of Japanese, Malaysian, Philippine, and Chinese divers and immigrant workers—often underpaid and driven to take on the most hazardous jobs that white Australians refused to take on—formed the backbone of the Australian pearling industry. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Australian pearls gained worldwide fame, primarily due to the efforts of thousands of immigrant workers from Asia alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander divers.

Dismantling the White Policy

In the aftermath of World War II, Arthur Calwell (1896-1973), who served as the Minister for Immigration in the Chifley government and was a strong supporter of the white Australia policy, allowed refugees from Europe and Eastern Europe, particularly from Poland and the Baltic countries, to migrate to Australia. Although they were not English-speaking, they were perceived as fair-skinned and blonde enough to assimilate successfully into the white Australians without posing a threat to the white Australia policy.

By the 1950s, it became evident that the strict implementation of not only the Immigration Restriction Act but also the Pacific Island Labourers Act and the Post and Telegraph Act, were significantly hindering population growth. By the early 1970s, the white Australia Policy was obsolete and was acknowledged as openly and shamelessly racist. The dismantling of this policy is notably tied to two names in Australian politics: Harold Holt and Albert Grassby.

In 1966, the Liberal Government, led by Harold Holt (1908-1967) passed the Migration Act, the first immigration law that enabled all potential non-European workers or immigrants with academic qualifications to apply for entry into Australia. The shift was groundbreaking, as immigrants were now being selected based on their skills and academic achievements rather than, as had been the case for over six decades, the color of their skin or country of origin.

Eight years earlier, the Migration Act of 1958 had repealed the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 by removing the application of the dictation test. While the Migration Act of 1958 effectively initiated the dismantling of the white Australia policy, it was not formally abandoned until 1973. In 1973, Albert Grassby (1926-2005), the Minister for Immigration in the government led by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam (196-2014), traveled to the Philippines and announced that the white Australia policy was officially dead.

“Give me a shovel and I will bury it,” he declared. Today, Grassby is widely recognized as the “father of Australian multiculturalism.” The same year, the Whitlam government implemented the Universal Migration Policy, which allowed individuals from any country to apply for immigration to Australia.

In 1975, the White Australia Policy was “definitively renounced” when the Australian Parliament passed the Racial Discrimination Act (RDA), which aimed to “ensure that everyone is treated equally, regardless of their race, colour, descent, or national or ethnic origin.” Additionally, the RDA made racial hatred unlawful and provided a series of examples of racial discrimination in employment practices. Requiring all employees to speak only English, for instance, is considered discriminatory. 70 years earlier, this requirement had been one of the pre-conditions for any immigrant who wanted to live and work in Australia.

Multiculturalism

In 1901, the year the Immigration Restriction Act was enacted, Australia had a population of approximately 3.8 million people, with 22.6 of them born overseas. According to data provided by the Commonwealth Parliament in its 2018 “Population and migration statistics in Australia,” the majority of those born overseas came from the United Kingdom, what is now Ireland, present-day Germany, and China, notably the only Asian country among the top five. The 1901 census also indicated that significant numbers arrived from New Zealand and present-day Sweden and Norway, as well as from South Sea Islands and British India.

Statistics from 1954 show a significant shift in immigration trends. While the United Kingdom remained at the top of the list, Italy took second place. Germany ranked third, while Poland replaced China in the fourth position. The Netherlands and Ireland followed, with New Zealand taking the place of the South Sea Islands, and Greece replacing India.

Between 1947 and 1981, the number of non-white individuals of non-European descent living and working in Australia more than doubled. After the end of the Vietnam War on April 30, 1975, and the dismantling of the white Australia policy, thousands of Vietnamese refugees arrived in Darwin, the northernmost city in Australia, seeking a new home.

A century after the passage and implementation of the Immigration Restriction Act, the Pacific Island Labourers Act, and the Post and Telegraph Act, the 2001 census revealed a dramatically different demographic landscape. While the United Kingdom still topped the list, New Zealand and Italy ranked second and third, respectively. In fourth and fifth places were two major Asian countries, Vietnam and China, with the Philippines and India occupying the eighth and ninth spots. By the 2016 census, the demographic composition of those born overseas had changed significantly once again compared to the 2001 results.

China, India, the Philippines, and Vietnam rose to occupy the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth places, respectively, ousting Italy. Notably, Malaysia and Sri Lanka filled the ninth and tenth places, resulting in six Asian countries being listed among the top ten countries of birth for foreign-born Australians.

The census data from 1901, 1954, 2001, and 2016 illustrate the profound impact that the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 had on Australian society and its demographic composition. For over half a century, strict immigration regulations created a predominantly white, insular society based on British and European values, while seasonal workers from Asia and the Pacific were often excluded or deported.

Today, thanks to the efforts of politicians such as Harold Holt and Albert Grassby—the latter commonly referred to as the “father of Australian multiculturalism”—Australia has become a multicultural society that thrives on the cultural and economic contributions from individuals coming from a diverse array of countries, including Vietnam, India, Italy, and the United Kingdom.