Can we know anything for certain? That’s the question behind David Hume’s Problem of Induction. Hume undermines the basis for using past experience to predict what will happen in the future, calling into question not only science and knowledge but also our everyday beliefs. If we can’t logically justify our confidence that the sun will rise tomorrow or that objects will fall to Earth, where does that leave us? We’ll explore Hume’s radical claims and their impact – and ask whether it’s possible to escape this bind.

Understanding Hume’s Problem of Induction

Induction is a technique of reasoning in which we derive general principles from specific observations. For example, if every swan we have ever seen is white, we might conclude that all swans are white. This kind of reasoning is deeply embedded in human thought and underpins a lot of science as well as our everyday decision-making.

But David Hume famously questioned this process, arguing that there is no logical justification for assuming that the future will resemble the past. Just because the sun has risen every morning up until now does not mean it will do so again tomorrow – yet this is what induction leads us to believe.

Hume’s critique is deeper than it first appears. It asks whether we can assume that the laws of nature will remain the same. For instance, how do we know gravity will work tomorrow exactly as it does today?

According to Hume, our belief in this consistency doesn’t come from logic itself. Instead, it is based on habit and custom. If something has always happened a certain way before, we expect it to happen like that again.

This raises an important question: if induction (our process of reasoning) lacks a logical foundation but our understanding of the world relies on induction, can we ever truly say we “know” anything for sure?

Hume’s Problem of Induction still looms large in philosophical skepticism today. It calls into doubt some of our most basic assumptions about what knowledge is and how reality functions.

The Principle of Uniformity of Nature

It’s commonly assumed that natural laws don’t change—this is known as the Principle of Uniformity of Nature. We are confident that things will always behave as they always have, be it gravity pulling downwards or water freezing at 0°C wherever and whenever.

This principle underpins both science and our daily lives. We need to be able to forecast outcomes (like tomorrow’s weather) in order to plan ahead or make decisions. But does it always hold true? David Hume wasn’t so sure.

David Hume questioned whether there is a good reason to believe in this principle. One might think that there is: after all, why wouldn’t things continue behaving as they always have done?

Hume observed that our belief in uniformity is based not on rational proof but on habit and custom. We have seen the same thing happen repeatedly and now expect it to keep happening.

For instance, because the sun has risen every morning until today, we are convinced it will rise again tomorrow. Yet this inference is not certain, merely probable – as Hume reminds readers with his illustration.

It follows disturbingly that confidence about what science (or induction) tells us rests psychologically more than rationally. It’s just how minds have been molded by experience. And this might undermine claims to know things for sure.

The Limitations of Empirical Knowledge

Hume’s Problem of Induction undermines the foundation of empirical science. These sciences use experiments and observations to learn about the world. However, there is a difference between this kind of knowledge, based on facts such as “the sun rises in the east,” and knowledge based on math or logic.

Math and logic provide truths that will never change. If something is true, then it must be so. Hume points out that all our scientific claims (and indeed most things we believe) fall into the first category.

As such they rest on induction for their justification. And this form of reasoning has no rational basis for assuming a regular connection between the future and the past.

Take, for instance, the case of water. Scientists note that at sea level, it boils at 100°C – from which a general law is derived. According to Hume, there is no logical reason why water must always boil at this temperature under such conditions. Rather, it is just habit (or custom) that makes us think it will.

This basic uncertainty affects all scientific theories and predictions. However, they have often been confirmed by observation. These ideas can never be established with total certainty as they are based on induction.

So, although science does offer highly effective ways of making sense of the world, Hume’s worry reminds us that any empirical knowledge will always have at least some element of risk attached. This point challenges how much trust we can safely place in scientific “facts.”

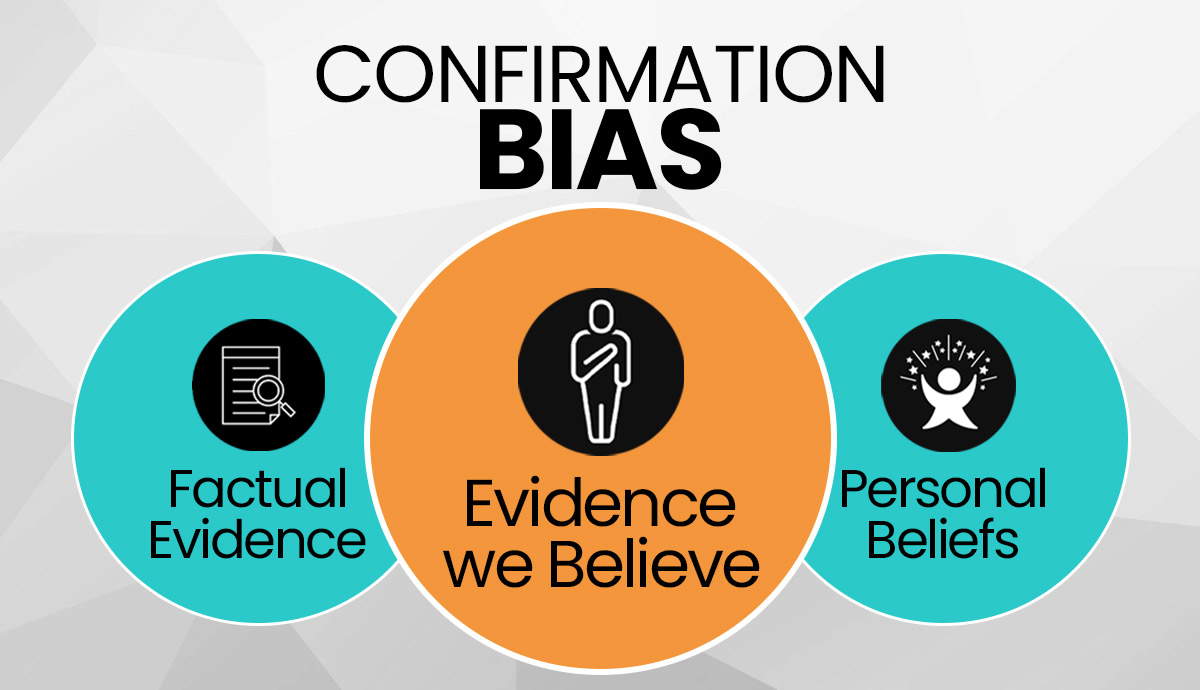

The Psychological Basis of Belief

Hume made a bold suggestion that our beliefs might spring more from psychological conditioning than rational deduction. Rather than being swayed by logical proofs, he said, we simply tend to think things that experience has shown us over and over again.

Take sunrise. We have watched the sun come up each morning since before we can remember – so isn’t it only natural for us to expect it will do the same tomorrow? In this view, belief in daily dawn doesn’t rest on argument but on habit or custom. It is an ingrained pattern that operates so smoothly we hardly ever notice what it’s doing.

Believing that if you let go of a stone, it will fall to the ground is similarly based not on reason. There is no way to prove logically that it must always happen this way.

Think about touching a hot stove. After getting burned, you become cautious around it, not because you have logically deduced that it is dangerous but due to the lasting impact of the pain itself. This realization has wide-reaching implications for human understanding.

If our convictions come from regular associations rather than rational assessments, then we ought to be very careful when making any claim to know something – particularly about things that will happen in the future. Hume’s way of seeing things leads one to doubt deeply that there is such a thing as knowledge at all.

Once it is understood that what we take to be true are just the effects of our minds’ habits, there arises an unsettling question: How can we ever know if anything lies beyond those facts immediately confronting us? This insight undermines not only everyday thinking processes but also the entire edifice of science.

Responses to Hume’s Problem of Induction

Hume’s Problem of Induction has sparked various philosophical reactions aimed at saving our understanding of science and knowledge.

Karl Popper provides one such response. He suggests the principle of falsifiability, which argues that while we can never prove scientific theories true through induction, we can subject them to stringent tests – and discard them as false if they fail.

For instance, consider the theory that “all swans are white.” No number of observations of white swans can substantiate this statement, yet just one sighting of a single black swan can refute it. In this way, Popper says, science shifts from making observations to avoiding them. It lets go of Hume’s skeptical puzzle entirely.

Another possible stance, such as Bayesian probability, provides a numerical system to modify beliefs depending on new data. This implies managing, rather than avoiding, uncertainty.

Pragmatism offers a similar idea. If beliefs help us get what we want, then they are useful things to have when guiding our actions – even if we can never be totally sure they are true. However, some people still wonder whether these two approaches are sufficient in the face of Humean doubt.

Although both Popperian and Bayesian methods (as well as pragmatism) give us ways to deal with an unpredictable world, there is nothing in their ideas that forces one to say Hume was wrong about induction not being rationally justified.

The question remains open: is it possible to move away from habits and social customs and towards real knowledge? Or must we always live with some level of either radical or mitigated skepticism?

The Implications for Modern Science and Philosophy

Hume’s challenge of induction still affects science and philosophy today. It changes what we think knowledge means – how sure can we really be about anything? In fact, his problem makes us take a step back when doing science: because of him, we know that all scientific ideas are only ever provisional.

Scientists these days don’t often say they’ve found out something once and for all. They will tell you their best theory given the evidence so far – but it could change tomorrow.

You can see this attitude at work when theories develop. People used to believe Newton’s laws of motion were definitely correct. But then Einstein came along with his theory called “relativity,” which showed us a different way to understand things moving – and now those old ideas from Newton seem a bit limited.

The acceptance of not knowing has been good for science. It has made researchers test ideas more carefully, think more critically, and check each other’s work. This attitude echoes what Hume said about knowledge. He urged people to be modest about what they could know because it might always be wrong.

But is any knowledge safe from doubt? Although some believe that each new discovery brings us nearer to the truth, others agree with Hume that there are some things we will never be sure of – no matter how many different ways we find to investigate them.

So, What Is Hume’s Problem of Induction?

David Hume’s Problem of Induction casts uncertainty on how we can learn facts about the world from just our immediate experiences. He questioned whether there is a logical basis for believing these things: perhaps it is just a habit we have gotten into?

When scientists make predictions, they assume that the laws of nature will hold up under all conditions. Yet, as Hume pointed out in his critique, this belief cannot be proved rationally – it may also simply be down to custom and past experience. So, there is an awkward question mark over science itself.

Hume’s idea puts us in an uncomfortable position: if our knowledge rests on habit rather than solid evidence, can we really “know” anything at all?

His problem prompts us to think more deeply about the limitations of human understanding. We might simply be making our best guess based on what we’ve observed previously.