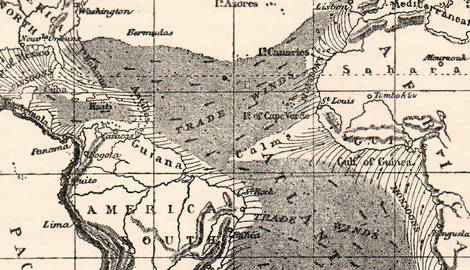

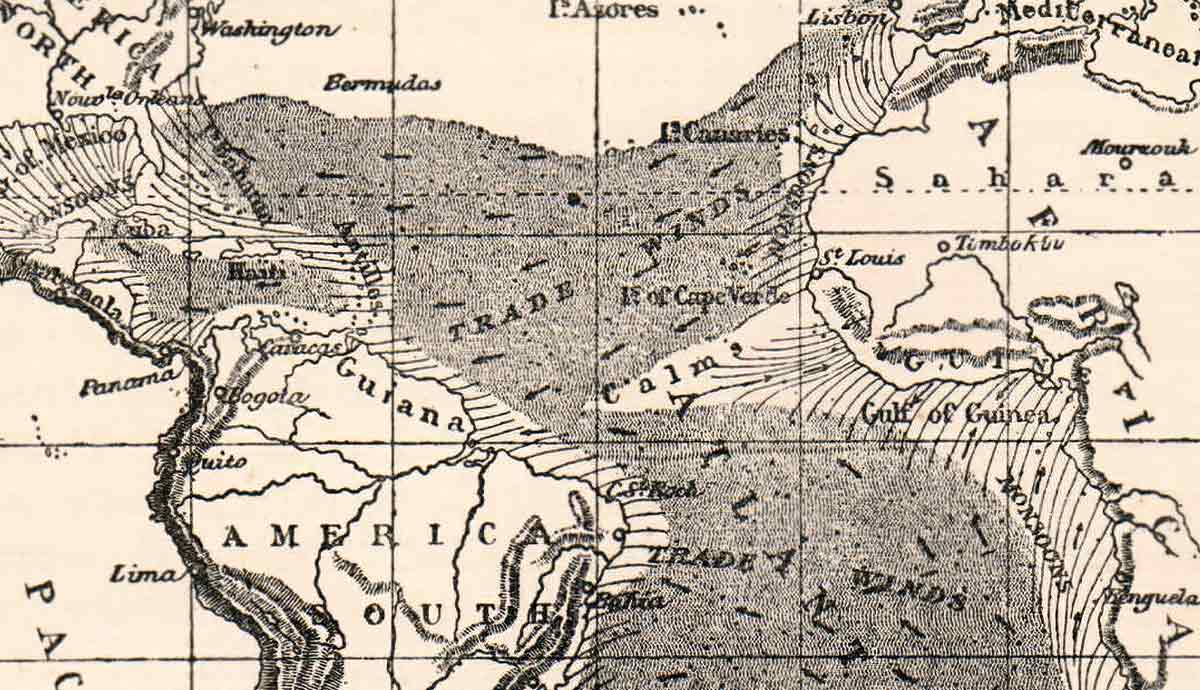

The permanent east-to-west blowing winds are a worldwide phenomenon. These predictable winds, driven by temperature and pressure differences, are sent east to west. This direction is dictated by the Earth’s rotation (Coriolis effect), which creates a consistent flow. Each hemisphere’s wind blew accordingly from southeast or northeast. Interacting with the ocean, the winds pushed the water along, creating reliable currents that so many mariners, settlers, and merchants depended on.

In Navigation and Exploration

Fate would have the Portuguese discover the Atlantic’s trade winds. By the early 1400s, Portuguese ships regularly sailed down the African coast. But this meant against the wind until they learned the volta do mar trick.

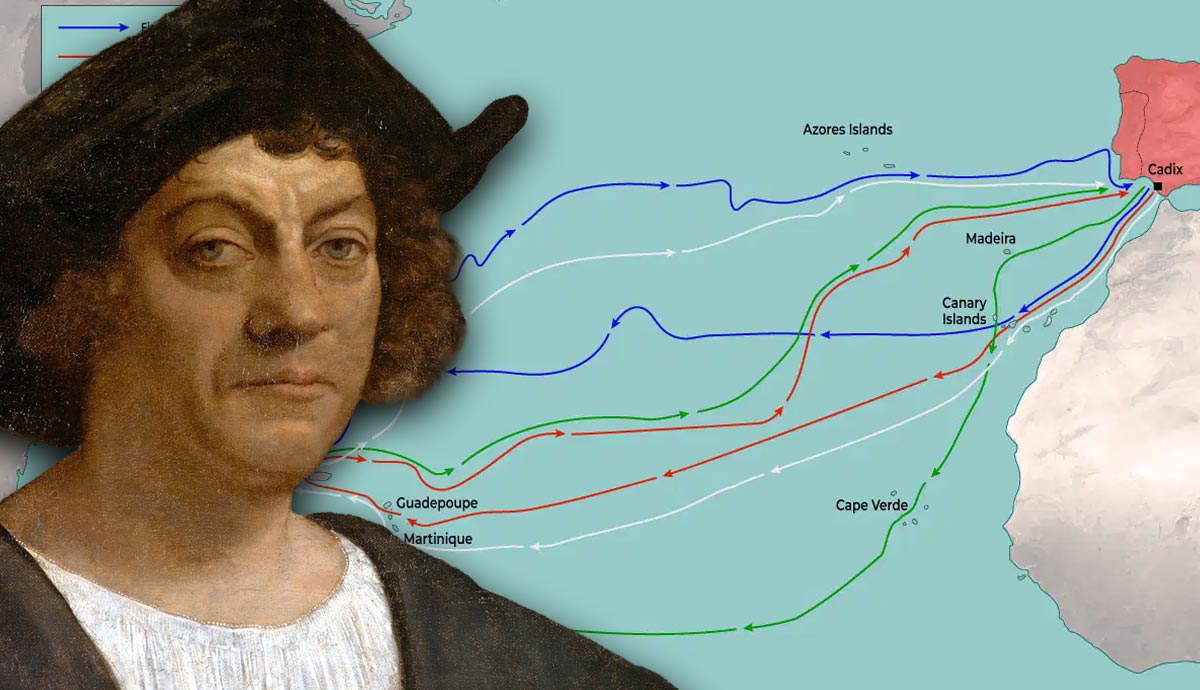

By using this trick, or “turn of the sea”, the Portuguese sailed into the Atlantic and caught the trade winds to hook back towards Europe. Soon, Columbus and the later Spanish galleons used northeast trade winds to reach America, particularly the Caribbean.

By trial and error, the Europeans found that the trade winds’ latitude positions, 30° N and 30° S, never changed. First, Columbus used this in his explorations. In the 16th-century Atlantic trade, their galleons gathered in convoys, dubbed the West Indies Fleet, gathered in Havana to catch “the trades” back to Europe.

Spanish navigator, Andres de Urdaneta, discovered the Pacific trade winds in 1565. A seasoned sailor, Urdaneta’s travels took him to locales like the Spice Islands, the Moluccas, and the Philippines. His knowledge of local currents led him to speculate that “westerlies,” or westward-blowing trade winds, existed.

To test this, Urdaneta sailed north, hoping to avoid doldrums and stormy seas around the equator. He sailed north, eventually catching a northeast current off Japan. Next, he encountered the westerly trade winds and, four months later, reached the California coast, proving his speculations. His route set up the Manila Galleon route, linking Asia and America for over two centuries. Ships returning to Spain would catch the trade winds, thus creating a global trading network.

The Trades, Magellan, and Circumnavigation

Even before Urdaneta’s groundbreaking trip, Magellan, or rather the remnants of his fleet, circumnavigated the globe. Spain hired Magellan in 1519 to seek a westward route to the Spice Islands. With a fleet of five ships and 270 men, Magellan skirted Africa’s coast before striking out into the Atlantic. He used the northeast trades for this, then the southeast trades for South America. Next, he passed through the Straits of Magellan.

This fleet relied on the Pacific southeast trades, which sent them northwest. For three months, they sailed before reaching Guam. Magellan perished fighting locals in the Philippines. One of his ships did reach Spain, demonstrating the global reach of the trade winds.

The Winds of Commerce

Though all this sailing and sailing accomplished much, the main driver was money. In a time without refrigeration, costly spices served as preservatives, changing Europe’s cuisine. With spices and other high-cost goods, one ship’s voyage could make or break a merchant.

Other significant commodities included silver from the Americas to Europe and Asia, silk, and luxury goods (such as porcelain). Also, sadly, the trades moved the transatlantic slave trade along, too, transporting humans from Africa to America. These unfortunates would fuel entire industries in the Americas, often in harsh or brutal conditions.

Enabled Colonization and Cultural Exchange

With sustained east-to-west airflow, the trades enabled true world empires. With these winds, European countries crossed the Atlantic and sailed into the Pacific’s far reaches to establish strongholds. Though still dangerous, these 16th- and 17th-century journeys became readily possible. For example, Spain used the Caribbean islands as jumping-off points. Spain, Holland, Britain, and France all built world-spanning empires.

Slowly, the strongholds became colonies via trade, exploitation, or even war. The trades became a sort of seaborne infrastructure, cementing imperial control over far-flung regions. Disruptions could be addressed much more quickly given the known winds.

Along with wind-driven colonization came cultural exchange. For example, languages like Portuguese and French spread, usually along with Christianity. Crops such as sugar, rice, corn, and rice radically changed diets worldwide. Maize would be an almost universal crop.

For the world, trade winds weren’t just a weather occurrence. These breezes became driving forces of empire, exploration, trade, and cultural exchange. They simply blew history forward, bringing change.