While modern celebrants welcome the new year on January 1 of the Gregorian calendar, the Inca, Aztec and Maya celebrated the dawn of a new year at various times—and sometimes multiple times. Given the challenges in reconciling ancient and modern calendars, pinpointing an exact “New Year’s Day” for these civilizations is no easy task. What is more certain is that in the ancient Americas, new year celebrations were often preceded by fasting and purification, followed by joyous celebrations honoring the gods and offering sacrifices to ensure their continued blessings in the year to come.

Inca New Year: Inti Raymi, June 24

Of the “big three” pre-conquest civilizations, the Inca new year celebration is the easiest to pinpoint, because it happens at the same time every year and is still celebrated today. The Inca welcomed the new year at the winter solstice, which occurs in June in the southern hemisphere. Held in honor of the sun god, Inti, it is believed the celebration, Inti Raymi or “Festival of the Sun,” was initiated by the Sapa Inca Pachacutec in the early 15th century.

The sun and the god responsible for it were essential to a prosperous year in Tawantinsuyu, the Inca Empire, so the celebration to thank Inti and ensure his continued blessings for the year to come was one of the largest in the empire. Thousands traveled to Cusco to celebrate during the festival, which, according to various sources, lasted somewhere between 9 and 15 days.

The celebration was marked by a period of fasting, followed by dancing, music, sacrifice and feasting. The mummified ancestors—past Sapa Incas and other nobility—were brought to the central plaza, where llamas were sacrificed, coca leaves were burned to forecast the future, and chicha beer was shared.

After the conquest, the Inti Raymi celebration was banned by the Spanish, the last formal celebration taking place in 1535. The feast continued to be celebrated in secret until the Viceroy of Peru formally outlawed it in 1572, along with other Indigenous practices and observances. Fortunately, famed Inca historian Garcilaso de la Vega had collected stories of the festival and its elements from family and friends, which he detailed in his book, Comentarios Reales de los Incas, so, though outlawed, the details of the celebration were not lost to time.

It was not until 1944 that the ceremony was formally revived. A group of Peruvian actors, in collaboration with the American Arts Institute in Cusco, staged a reenactment of the great festival based on de la Vega’s writings. It was so popular it became an annual event, and in 2001, was officially declared part of the Cultural Heritage of the Nation.

Today, a large Inti Raymi festival and reenactment is staged every year in Cusco on June 24, with smaller celebrations and processions in the days leading up to it. With reenactors dressed in traditional attire, the celebration begins at Qorikancha, the Temple of the Sun, with the opening ceremony. Participants then proceed to the Plaza de Armas, where locals and tourists alike listen to the Sapa Inca’s speech and observe various rituals to honor Inti, including offerings of coca and chicha. The final event takes place at the fortress of Sacsayhuamán, with additional rituals and symbolic sacrifices to the sun god—fortunately the ritual llama sacrifice element is left to the imagination. Traditional dances and music are performed throughout the day, locals often prepare traditional dishes for their families in celebration, and thousands of tourists pour into the country to take it all in.

Mexica New Year: Yancuic Xihuitl, March 12

Two different calendars were used in the Aztec Empire: a 260-day ritual calendar and a 365-day annual “civil” calendar based on the solar year. This yearly calendar was divided into 18 20-day months, which left five “empty” days at the end of the cycle during which the Mexica prepared to welcome a new year.

The last five days of the year, or nemontemi, meaning roughly “wasted days,” were considered a dangerous time. While each month in the calendar was dedicated to a particular deity, these five days had no patron or protector. Many everyday activities were put on hold to avoid calamity, and a period of fasting or reflection to prepare for the new year was observed.

As with the modern new year, much of the preparation and celebration took place the “night” before—though records indicate that the Aztec day began at 6 am, rather than midnight. When the new year dawned, it was heralded with the blowing of conch shells, while priests performed cleansing and other rituals designed to ensure a prosperous new year, particularly honoring the gods who would be responsible for good harvests.

Chronicles from the immediate post-conquest period offer different dates for the festival, interpreted through the Julian calendar in use at the time. Most modern scholars have placed the festival as likely falling sometime in late February or early March of the current Gregorian calendar. Today, many Nahua peoples celebrate the new year on March 12, staging events full of ceremonial dances and music, and lighting candles as well as more modern fireworks. Conch shells are still blown to welcome the special day.

An even more significant “new year” festival was celebrated when the renewal of the 365-day and 260-day calendar cycles coincided. This occurred every 52 years and was celebrated with the New Fire Ceremony, somewhat akin to heralding a new century today. Like the “wasted days,” the end of the 52-year cycle was a dangerous time. The Aztec believed that the world had ended and been recreated multiple times, and the end of any 52-year cycle could bring it to an end again.

As the day approached, the people would destroy their personal belongings to rid themselves of the old, practiced ritual bloodletting, fasted and purified themselves. All fires, including sacred fires kept burning throughout the 52-year period in the temples, would be extinguished on the final day, and the Empire’s priests would come together and attempt to start a new fire. If it didn’t catch, the world would come to an end. But if it did, it was used to relight fires throughout the region, spread by relay runners, and a great celebration ensued. Captives were sacrificed, blood offerings were made to the new fire, and the people feasted to welcome another 52-year period safe from the apocalypse.

Maya New Year: July?

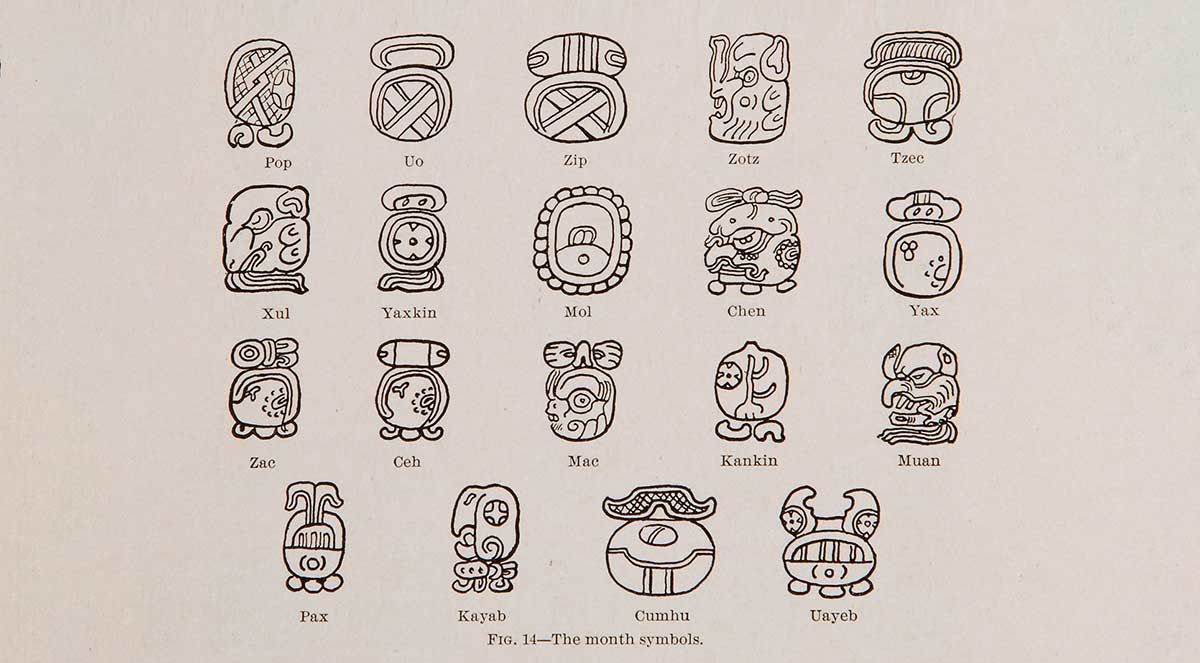

In close proximity, particularly in the Yucatan peninsula, the Aztec and Maya civilizations shared many spiritual beliefs and cultural elements, including the use of multiple calendars. Some scholars suggest both groups inherited these calendar concepts from the Mesoamerican “mother” culture, the Olmec. The Mayan Haab’ calendar mirrored the Aztec civil calendar, with 18 20-day months and a short month of 5 “leftover” days called Wayeb’.

During Wayeb’, the Maya prepared for the coming new year with special cleansing rituals, fasting and reflection. The first day of the new year was, arguably, 1 Pop, though some historians suggest that a correct reading of the Mayan calendar indicates that day 1 was actually referred to as 0 Pop. The day before was called the “seating of Pop,” akin to “New Year’s Eve,” and was marked by divination rituals intended to predict the course of the upcoming year. Each month of the Mayan calendar cycle had a particular patron god, and so on the day before, he would take his “seat” to prepare for the year ahead.

Though the Mayan system of calendars, particularly the long count, was precisely calculated, the Haab calendar did not take into account the discrepancy between the 365-day count and the actual length of a solar year: 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, 45 seconds. What this means to modern humans is that the first day of the Mayan year does not fall on a consistent day every contemporary year. For example, according to modern calendar conversions, in 2025, 1 Pop fell on March 31, but 20 years ago, it occurred in early April. Because the beginning of a new agricultural cycle takes place in July, this is often a month for new year celebrations within the remaining Maya communities, usually around the 26th.

However, celebrations of the sacred new year, meaning the first day of the Mayan ritual calendar, known today as the Tzolk’in in Yucatec Maya and Chol Q’ij in K’iche Maya, are more common. Wajxaqib’ B’atz is commemorated every 260 days, particularly by the K’iche Maya in present-day Guatemala. The event is marked by the selection of a new “calendar keeper,” a spiritual guide for the next 260 days. Because this calendar’s cycle is so much shorter than the 365-day modern year, Wajxaqib’ B’atz can take place on any date; in 2025 it took place on October 5.

In addition, it’s worth noting that the Mayan Empire had collapsed long before the conquest, leaving behind more independent communities that developed their own rituals and practices. By the time of European contact, few were left who could interpret or explain the various calendar systems used centuries earlier by their ancestors—or cared to risk encountering the Spanish to do so. Much of what is believed about the Mayan calendars, and attempts to reconcile them with the modern calendar, has come through centuries of archaeological work, which is still ongoing.