In the more than 500 years since Europeans first made contact with the native peoples of the Americas, many Indigenous customs, practices and celebrations have been erased. Yet, over those same centuries, many with Indigenous roots fought to preserve the ancient rituals their ancestors held dear. Though some aspects have become intertwined with traditions and beliefs introduced by colonizers, these five Aztec, Inca, and Maya festivals are still celebrated in some form in the modern day.

Day of the Dead: Celebration of Life

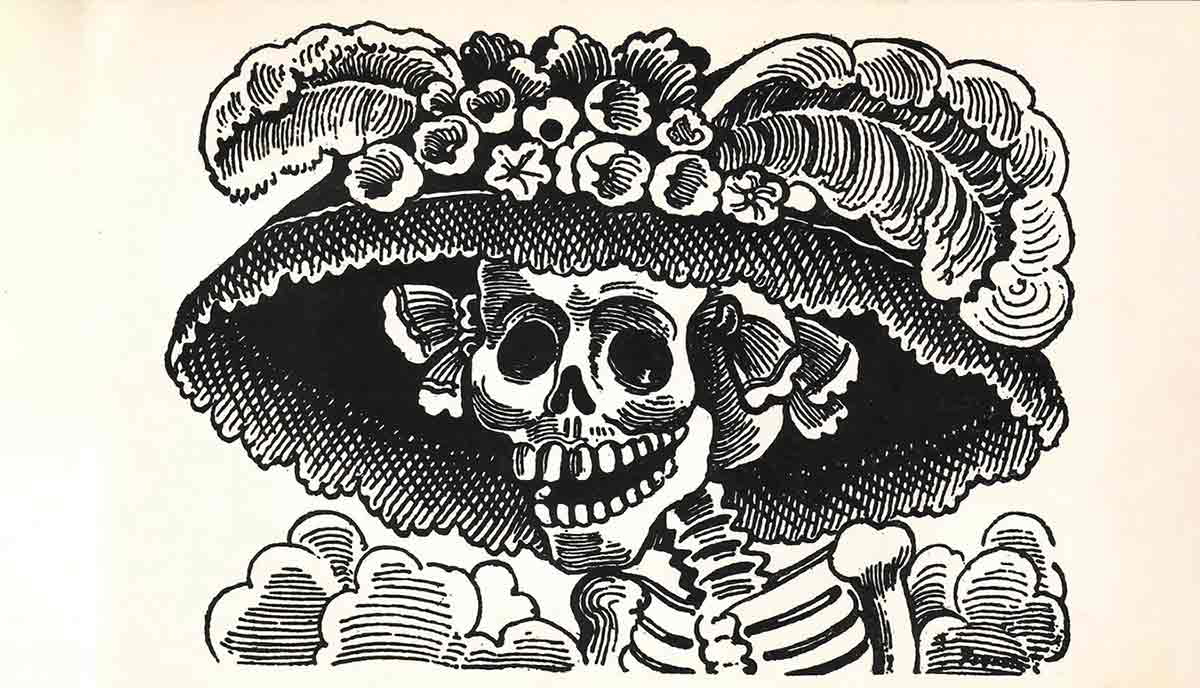

Mexico’s most famous celebration is also, arguably, one of the hemisphere’s oldest. Though replete with Catholic and European influences, most scholars agree that Día de los Muertos, Day of the Dead, can trace its roots to Mexica festivals honoring the dead and the gods of the underworld that were co-opted by the Church and fused with the Catholic All Souls’ Day.

What, exactly, those celebrations entailed and how much of the current holiday is drawn from Indigenous practices is a matter of debate. Many scholars believe Day of the Dead draws its greatest inspiration from an Aztec ritual during which offerings were made to the underworld goddess, Mictēcacihuātl, as thanks for caring for the dead. The grinning skull, or calavera, that has become ubiquitous in modern Day of the Dead celebrations is believed by some to have been inspired by depictions of the Aztec death goddess. Those celebrations, like most other Aztec festivals, likely involved rituals performed by priests—bloodletting and sacrifice—which aren’t elements of the contemporary holiday.

The Aztec and other Mesoamerican cultures devoted entire months to commemorating not just the underworld goddess, but all the dead, giving rise to several traditions seen in modern Day of the Dead celebrations. A practice of leaving food and gifts to help the dead traverse the nine levels of the underworld, for example, likely merged with Spanish traditions into the ofrendas created for the holiday today.

Cempasúchil, or marigolds, are an essential part of the Día de los Muertos today, and their use is also likely derived from Indigenous traditions. The fragrance of the cempasúchil was believed by Nahua peoples to attract and guide the dead. The burning of copal to purify the environment for the returning dead is almost certainly rooted in Indigenous traditions, as is the ubiquitous face painting, a well-documented Aztec practice. Other elements—sugar skulls, pan de muerto, paper garlands—are distinctly modern.

Most significantly, the timing of the Day of the Dead celebration has been changed. The Aztec feasts of the dead were celebrated during what are today August and September; Spanish efforts to stamp out and replace Indigenous practices with Christian ones shifted celebrations honoring the dead to coincide with All Saints Day, November 1, and All Souls’ Day, November 2.

Qoyllur Rit’i: Syncretic Celebration

Before the colonizers introduced Christianity, the Incas worshiped a pantheon of gods as well as smaller mountain spirits, apus. Pilgrimages into the mountains were a common way to honor these spirits, and the plausible origin of the modern Qoyllur Rit’i pilgrimage and celebration. Meaning “festival of the snow star” in Quechua, Qoyllur Rit’i is, officially, a yearly pilgrimage to a location where, according to legend, Jesus Christ once appeared in the form of a child. The actual root of the pilgrimage is murkier.

Extant records indicate that Ausangate mountain, one of the tallest in Peru and in the same region as the festival, was one of the most important apus at the time of the conquest. Scholar Robert Randall also notes that the timing of the snow star festival coincides with the reappearance of the Pleiades constellation in the night sky, an event marked by celebration in the Inca Empire—and one that seems more relevant to the name “snow star” than an apparition of Christ.

The Church, on the other hand, holds that the pilgrimage began to honor a miraculous apparition of Christ, who appeared in the form of a child and befriended a local peasant boy, Marianito. When Marianito brought the church elders to meet his new friend, the Christ child transformed, brandishing a tree trunk in the shape of a cross. Marianito died of shock and was buried beneath a large black rock nearby, which villagers began to visit to honor the event. Some scholars note that the apparent “worship” of a rock sounds more Indigenous than Christian, and further suggest that the appearance of this legend, coinciding with the last significant Indigenous rebellion under Tupac Amaru II, indicates an attempt to stamp out an Indigenous cult of worship at a challenging time and replace it with a more palatable Christian festival.

Whatever the true origin, today the Qoyllur Rit’i celebration includes both Indigenous and Catholic elements in a syncretic festival that draws pilgrims from throughout the Andes. It includes various processions with the Lord of Qoyllur Rit’i, dance performances, pilgrims adopting traditional dress to play specific roles in the event, and the extraction of blocks of ice from the glacier, to be used as holy water in the coming year.

Wajxaqib’ B’atz: New Year Celebration

Recording time over multiple calendars, including the 365-day solar calendar, the 260-day ritual calendar, the 52-year calendar round and the long count calendar, the Maya no doubt had numerous celebrations and festivals to mark important days. With the collapse of the Maya civilization, many of those events have been lost to time, but some of the most important celebrations have been kept alive for hundreds of years, particularly in more isolated Maya communities.

The ritual marking the restart of the 260-day ritual calendar, Wajxaqib’ B’atz, is among the surviving celebrations, still observed among the K’iche Maya in Guatemala. The ritual calendar of the Maya consists of 13 numbers and 20 day names; it restarts after each day name and number have coincided once, which occurs every 260 days. While Wajxaqib’ B’atz can be translated as “8 monkey,” and marks the restart day, the day name b’atz is, notably, also associated with the thread of time.

How this important day was celebrated at the peak of the Mayan civilization is unclear, though scholars believe Mayan celebrations often involved blood letting and sacrifice, offerings to the gods, dancing and feasting; this celebration likely included some of the same.

Rituals practiced today may provide further clues. Participants travel to sacred places, including caves and mountains, to pray, burn incense, and make offerings to sacred fires constructed on circular altars. As the year restarts, “day keepers” are appointed or renewed during sacred ceremonies. These members of the community will act as spiritual guides for the next year, keeping track of important dates and carrying out various rituals, as well as consulting with the deities and spirits in order to advise members of the community.

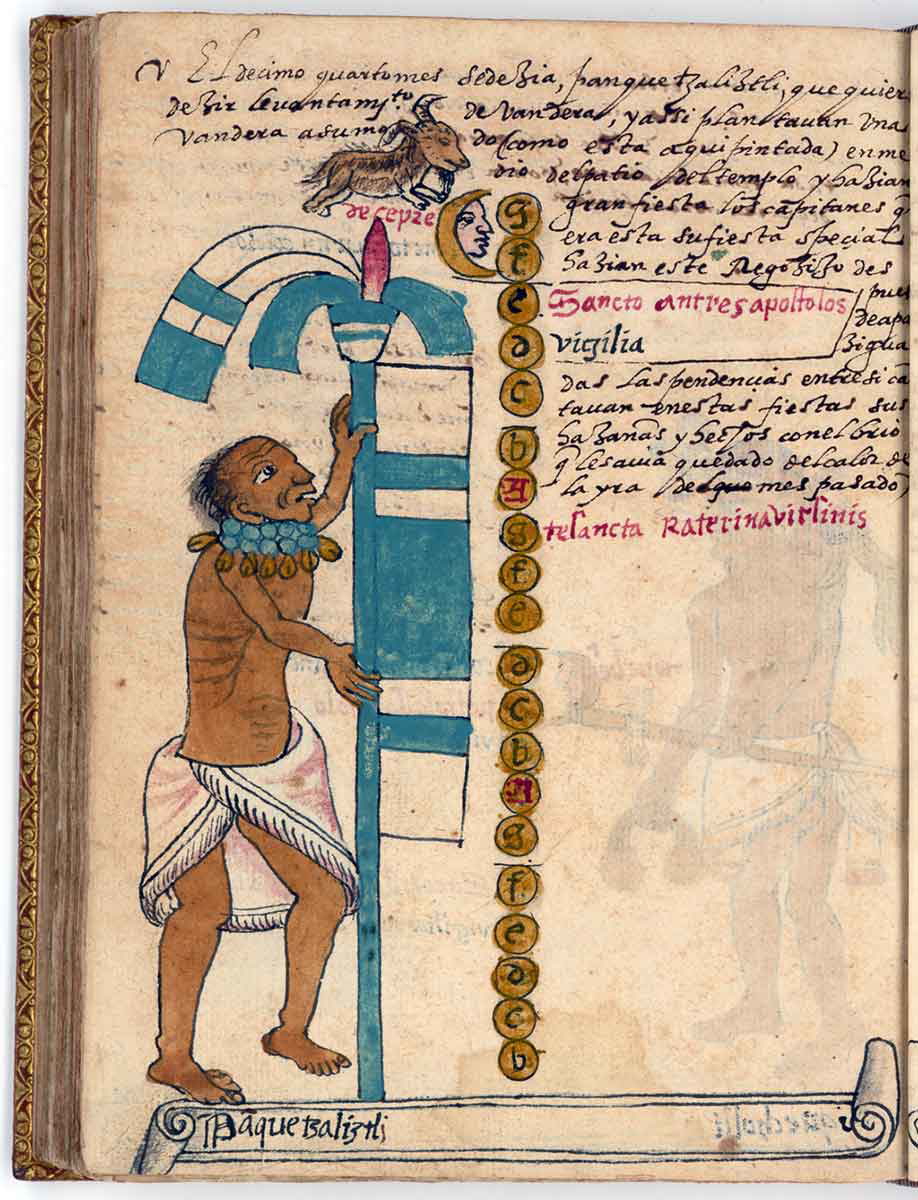

Panquetzaliztli: Birthday Celebration

So many elements of the Aztec Panquetzaliztli remain, it seems fair to say it’s still celebrated, at least in spirit. Once a Mexica celebration of the birth of the sun god Huitzilopochtli, coinciding with the winter solstice, the timing of this festival led to a co-mingling with Christmas in the centuries since the conquest.

Panquetzaliztli, or “raising of banners,” was celebrated in the weeks leading up to the solstice with dancing, feasting, simulated battles, and a foot race in which an effigy of Huitzilopochtli was carried through the streets. Obvious parallels between celebrating the birth of a Mexica deity and the birth of Jesus Christ made it relatively easy for Spanish evangelists to co-opt Panquetzaliztli and largely replace it with European Christmas traditions. Though the ritual sacrifice and battle reenactments of Panquetzaliztli are gone, many elements of the original celebration remain and have been incorporated into modern Christmas celebrations, including two particularly recognizable ones: las posadas and poinsettias.

Las posadas is a tradition of ritualized processions over nine days, reenacting Mary and Joseph’s journey through Bethlehem seeking shelter. On its face, it seems distinctly Christian, but it is not a Christmas custom practiced outside Mesoamerica. Notably, the Panquetzaliztli festival involved processions to specific locations around Tenochtitlan, where sacred rituals were performed, leading scholars to conclude that las posadas evolved from that tradition.

Poinsettias—cuetlaxochitl in Nahuatl—are native to present-day Mexico and bloom around the time of the Panquetzaliztli celebration. Cultivated by the Aztecs for spiritual and medicinal use, their bright red color was associated with blood sacrifice to Huitzilopochtli and the flowers were often used to decorate temples, particularly during Panquetzaliztli and other festivals that honored the sun god. Christian evangelists made use of the flower’s star shape to relate it with the star of Bethlehem and incorporated it into Mexican Christmas celebrations.

Pa ‘Puul: Nature Celebration

Throughout the pre-conquest American empires, festivals were held to honor deities as well as elements of the natural world that were essential to survival. Rain was arguably the most important of these natural elements—sufficient rainfall was at the root of a thriving civilization.

Pa ‘Puul, or “breaking pots” was a Mayan ritual to petition the gods for rain and, subsequently, good harvests. Whether it was an annual festival or a ritual practiced in times of drought is unclear. Today this festival is celebrated annually in June by the Maya in Yucatan, Mexico.

The day’s festivities begin with children being sent out to collect animals the Maya traditionally associated with rain, primarily lizards and frogs. These animals are then placed in pots to await the start of the ceremony. Once the pots are filled, they’re broken, releasing the animals and creating a sound mimicking thunder, believed by the Maya to encourage rain. Some accounts indicate that the freed animals are believed to return to the wild to tell the gods that rain is needed.

Today, with the Christianization of most of Mesoamerica, the festival has become associated with St. John the Baptist, whose feast day is June 24. As in other Indigenous communities, a legend attributing a miracle to the saint—in this case, much needed rainfall—has resulted in traditional rituals being transferred to the Church and its calendar.