The Inca Empire ruled a vast territory for nearly a century, yet its power relied on more than force. At its core lay the Qhapaq Ñan, a network of roads and trails that became the empire’s backbone. Stretching over 25,000 miles from Colombia to Peru, Chile, and Argentina, it crossed some of the most rugged terrain on earth. Hundreds of stops along the way sustained armies, traders, pilgrims, and runners, binding the Andes into one of history’s greatest empires.

A Road Without Wheels

When people think of mighty road networks, it is usually Rome that comes to mind. But long before the Spanish set eyes on Cusco, the Inca had already mapped a system to rival anything in the Old World. The difference was in design. While the Romans built for wagons, carts, and cavalry, the Incas built their trails for runners, llamas, and steady feet. The Inca world had neither transport, wheels, nor horses until the Spanish arrived.

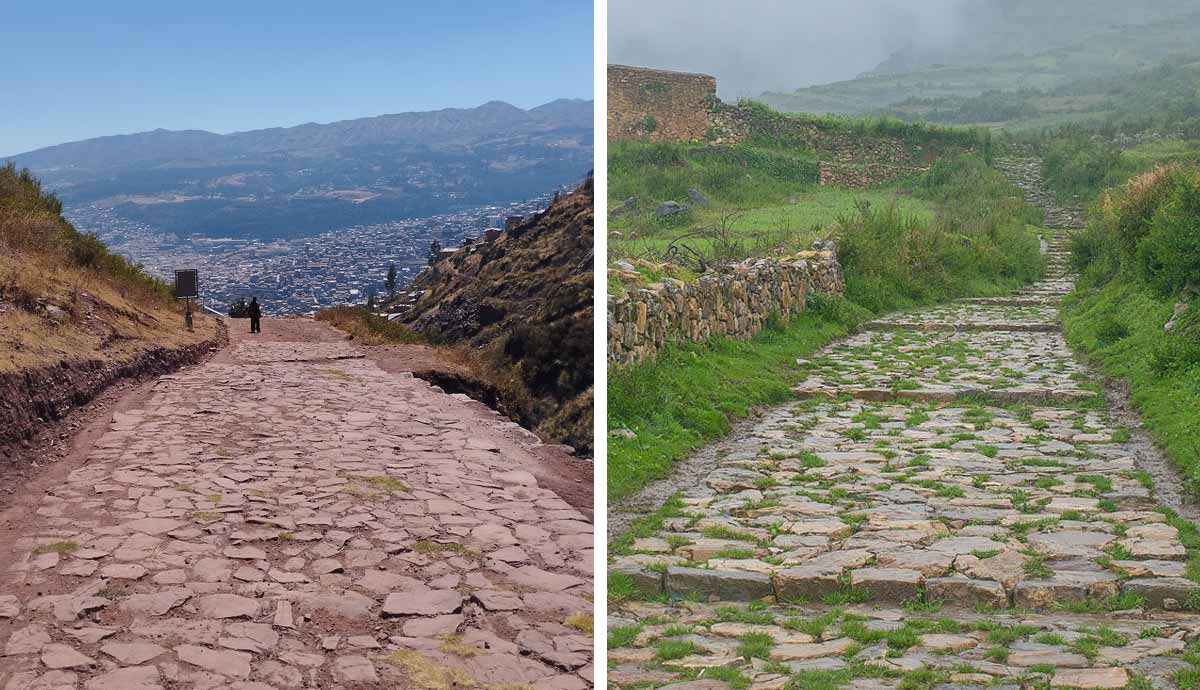

The old Andean roadway was a network of paths that were narrow and purposeful, hugging cliffsides, zigzagging across valleys, and climbing heights that would make most modern roads impossible. Yet the scope was staggering. By connecting the capital at Cusco with every province, the Inca ensured that no corner of their empire felt too remote nor too disconnected.

Did you know? The Qhapaq Ñan was so vast that if you placed all its routes end to end, it would almost circle the Earth.

Carved Into Mountains and Hung Over Rivers

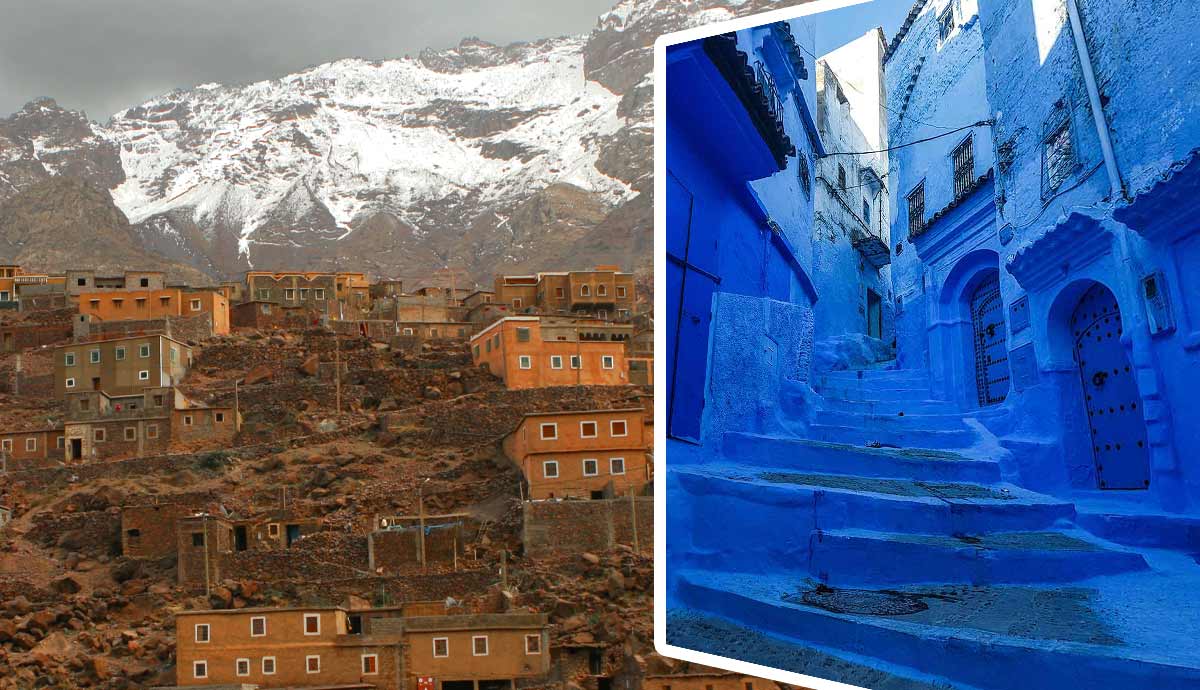

The Andes are some of the harshest landscapes on the planet, yet the Inca found ways to carve paths through them. They paved trails with stone so they could survive centuries of use, built retaining walls to hold slopes in place, and cut staircases directly into cliff faces. Tackle an Inca trail nowadays and you’ll no doubt feel awe-struck. The labor and ingenuity it took to build passages where there was nothing but rock and thin air is astonishing.

Some of the toughest hurdles the Incas had to cross were rivers, yet they found ingenious ways to cross them. Rather than laying heavy stone bridges, they turned to something much lighter and surprisingly sturdy: ichu grass. Communities would harvest, twist, and braid the grass into thick ropes, which would then be woven into suspension bridges stretching across deep gorges.

Naturally, the work didn’t end once the bridge was built, and regular maintenance was required. As expected, the Incas turned this into a ceremonial event. Every year, entire villages would gather to weave new ropes, replace the ropes, again turning something practical into a ceremonial endeavor. For people living in isolated valleys, these crossings were near-sacred lifelines. These pivotal links kept them connected to markets, festivals, and the empire beyond their mountains.

Did you know? The Q’eswachaka bridge, near Cusco, is still rebuilt every year by local communities using traditional methods passed through the generations.

The Empire’s Fastest Messengers

If the roads were the arteries of the empire, the chasquis were its pulse. Trained to sprint short distances from a young age, the Inca runners carried verbal reports or quipus knotted with data. They would hand messages off at tambos, small waystations where food, shelter, and another runner awaited. With this ingenious relay system, information could travel hundreds of miles in just a matter of days.

Once the Spanish conquistadors realized how the Incas ran their empire, they were stunned by the efficiency. Fresh fish from the Pacific could arrive in Cusco, over 300 miles inland, before it spoiled. Orders from the emperor in Cusco reached distant provinces in days rather than weeks. For a world without wheels or written mail, this was a communications system as advanced as anything in Europe.

Did you know? Inca relay runners could cover up to 150 miles in a single day, making them faster over long distances than mounted couriers in Spain.

Highways to the Heavens

While many Inca trails were used to move goods or armies, others had a deeper spiritual use, linking shrines, mountain huacas, and ceremonial centers. The paths themselves often followed sacred alignments, mirroring the paths of the sun, moon, and alignments showcased in Machu Picchu.

In some regions, the journey mattered about as much as the destination. A mountain pass might be marked with cairns or offerings to appease the apus, the powerful mountain spirits, and communities maintained daily rituals that blended life with faith.

Did you know? Some Inca roads doubled as processional routes for festivals, where dancers, musicians, and pilgrims filled the paths on their way to sacred ceremonies.

Control Through Connection

The Inca roads were not just a clever convenience; they were the backbone of how the empire stayed in control. Armies could be on the move within hours, quashing uprisings before they had a chance to spread. Officials traveling between provinces didn’t have to rely on local generosity either. Waystations stocked with food and supplies meant they could cover long distances without draining communities along the way.

The network also made it possible to shift resources where they were most needed. If one province were hit by drought, surplus grain from another could be sent quickly to keep people fed. Even the empire’s labor tax, known as the mit’a, depended on the roads. Communities sent workers to Cusco or major building projects, and what they produced could then be distributed back out again, all thanks to the trails that stitched the Andes together.

Did you know? History eventually showed that the power of the Inca Empire was only as strong as its ability to keep its maze of pathways open and maintained.

When Your Lifeline Is Turned Against You

When the Spanish arrived in the Andes, they soon realized that the Inca Empire relied entirely on its intricate, and to them, unique road system. The empire’s labor had carved trails through mountains and across valleys, and the newcomers wasted no time making use of them. Marches that might have been impossible in such rugged terrain suddenly became manageable. Ironically, the genial road system that created the Incas’ dominion would become the key to its downfall.

Yet the Spanish, proficient as they were at colonizing by now, also realized that what made the roads so valuable also made them dangerous. A well-kept network could just as easily support resistance against colonial rule. To prevent that, many sections of the Inca trail were dismantled, left to crumble, or repurposed for their own construction.

Did you know? The Spanish relied so heavily on Inca roads that entire expeditions, including the march on Cusco, followed these ancient routes almost step for step.

Where the Roads Still Live

The fall of the Inca Empire and the arrival of European horses and carts left much of the Qhapaq Ñan to fade. Yet countless sections remain. Farmers still use the trails to reach markets, shepherds guide their llamas across them, and hikers tread paths to famous sites like Machu Picchu.

The classic Inca Trail may be the most celebrated, but there are countless other routes worth exploring, from the demanding trek to Choquequirao to remote sections in Bolivia and Ecuador that pass through landscapes little changed since the days of the empire. In recognition of their enduring importance, UNESCO declared the Qhapaq Ñan a World Heritage Site in 2014, protecting parts of the road in six countries.

The most extraordinary aspect of the Inca Empire’s road system is that only a quarter of it has been fully mapped, meaning much of it still lies hidden beneath modern roads or untouched landscapes.