Columbus may have sailed in pursuit of gold, but what he and his successors found was a new world full of never-before-seen plants, animals, and even technology. From unique foods to mind-boggling tools and skills, civilizations in Meso- and South America wowed newcomers with everything from chocolate to brain surgery, pioneering or perfecting inventions we still use today.

1. First in Freeze Drying

Before every home had a refrigerator, food preservation was considerably more difficult. Yet, without the advantages of rapid modern transportation and agricultural practices used to counteract drought and pestilence, preservation was essential to survival. Long before kids could snack on the wonder that is astronaut ice cream, the Inca were the first to preserve food using a technique known as freeze-drying.

Freeze-drying is a preservation method that allows food to retain much of its original flavor and nutrients. Modern freeze-drying techniques use equipment to freeze the water in the food in question and then remove it by converting the ice to vapor and vacuuming it out. Removing the water content eliminates the moisture bacteria that need to grow, creating spoil-resistant food.

For the Inca, freeze-drying was a practical way to preserve an essential food, potatoes, utilizing the unique climate of the Andes. Not only did freeze-drying allow potatoes to be stored for long periods in case of drought, but it also made them lighter and easier to transport, ideal for soldiers on the road.

Freeze-dried potatoes, or chuño, from the Quechua ch’uñu, meaning “frozen potato,” predate the arrival of the Spanish, but the first recorded evidence of their existence comes from Spanish chroniclers in the late 16th century. To create chuño, farmers in the Andes would lay potatoes out to freeze at night, then dehydrate them in the strong sunlight during the day. After repeating this process several times, the potatoes would then be smashed, literally trampled underfoot, and go through several more rounds of freezing and dehydrating. The result is a preserved potato product that lasts for years. It’s often rehydrated in soups or other dishes, or they are ground and used as a type of flour.

The Inca didn’t use freeze-drying solely for potatoes. It was also notably used for meat to create a product far more widely known than chuño: jerky. While more traditional smoking and salting were likely used in the lower altitudes, up in the Andes, thin slices of llama or alpaca meat were treated much like potatoes, alternately frozen and sunbaked to create a dried meat that could be easily preserved and transported. The conquistadors apparently took more of a liking to ch’arki than chuño, adopting the snack and spreading it and its name around the world.

2. Masters of Skull Surgery

Something as delicate as brain surgery seems like it would be impossible without modern medicine, not to mention hygiene. However, primitive forms of brain surgery were performed as early as 5,000 years ago.

One of the civilizations to not only perform brain surgery, or trepanation, thousands of years ago but to do it regularly and well was the Inca. More trepanned skulls have been found in modern-day Peru than anywhere else in the world, and the success rates for those surgeries are among the highest for any pre-modern civilization that performed the procedure.

Trepanation is a broad term that encompasses boring, scraping, or cutting into the skull for any number of reasons, though often to address head trauma. Without antibiotics or anesthesia, it sounds like a nightmare at best and a death sentence at worst. But the Inca not only used the practice regularly, they became highly skilled.

The arid climate of the Andes lends itself to archeological preservation, which means scientists have been able to study hundreds of Inca and pre-Inca brain surgery patients. The earliest skulls studied in the region, dating back to 400-200 BCE, show survival rates around 40%. For comparison sake, researchers highlighted that the survival rate for battlefield trepanation during the American Civil War, over 2,000 years later, averaged about 50%.

But at the peak of the empire’s skill, the survival rate, as evidenced by healing around the incision site, was as high as 80%. Scientists even observed two skulls with seven healed incisions a piece, indicating that the procedure was not only used to treat the type of head injuries sustained in battle but also to try to address internal maladies, perhaps headaches or epilepsy.

So, how did they do it?

The archaeological evidence suggests that the practice was refined over time. Skulls have been discovered with post-mortem trepanation, indicating that Inca surgeons were studying anatomy to improve the procedure. As their knowledge expanded, the size of the holes being made shrank, and the technique shifted from boring holes in the skull to a less risky, gradual scraping away or “grooving” of bone that reduced the chances of puncturing the protective membrane around the brain. The site of the incisions also moved away from areas of the skull most likely to cause heavy bleeding.

The Inca also had a wide knowledge of medicinal herbs that may have been used to anesthetize patients and possibly prevent infection. Though there is no evidence linking these herbs directly to the trepanation procedure, Inca use of coca leaf as a topical pain killer, cinchona bark to lower fevers, and chicha, a fermented corn beer, as a pseudo-anesthesia to induce unconsciousness are all documented.

3. Chewing Gum Gurus

Anyone who’s ever stepped on a wad of chewing gum carelessly discarded on the sidewalk has probably cursed the person who invented it. But despite the rage induced by having to remove the sticky substance from shoes, clothes, and hair, the habit of chewing gum has persisted for an impressively long time.

Various cultures developed a practice of chewing plant-derived substances, including the ancient Greeks. However, modern chewing gum has its roots, literally, in the Aztec Empire and the sapodilla tree, native to Mesoamerica and the Caribbean.

When injured, the sapodilla tree secretes a sticky resin to cover and protect the damaged area. The Aztec, as well as the Maya, developed a practice of harvesting and chewing this latex. It has a slightly sweet flavor, and they sometimes mix it with additional ingredients to improve the texture. The word for this substance, tzictli in Nahuatl, became chicle in Spanish, and is also where the name Chiclets, one of the most well-known chewing gum brands, came from.

Gum chewing in the Aztec Empire was not a free-for-all. While it was done to freshen breath and clean teeth, much like today, social norms determined who could chew tzictli and where. According to Spanish chroniclers in the 16th century, only unmarried women and children could chew gum in public without judgment. Married women could chew gum in private, and gum chewing by men was frowned upon altogether.

Though a variety of chewing gums were produced from tree resins and saps in the early Americas, modern chewing gum was first developed from tzictli in the late 19th century. Former Mexican leader Antonio López de Santa Anna, living in exile in the US, imported chicle from his home country and gave some to collaborator and inventor Thomas Andrews to develop as a rubber substitute.

Failing to make chicle a success in that regard, Andrews instead developed it into a commercial chewing gum. In 1899, he incorporated the American Chicle Company in New Jersey, and various chewing gum companies continued to import and use chicle to produce commercial chewing gum. Ultimately, chicle was replaced by synthetics in the 1960s.

4. Popcorn Purveyors

Maize, of the standard and popping varieties, spread throughout the pre-conquest Americas as early as 4000 BCE, and into the present-day southwestern US by approximately 2,500 years ago. However, the process of domesticating this staple food was a long one that began in present-day Mexico.

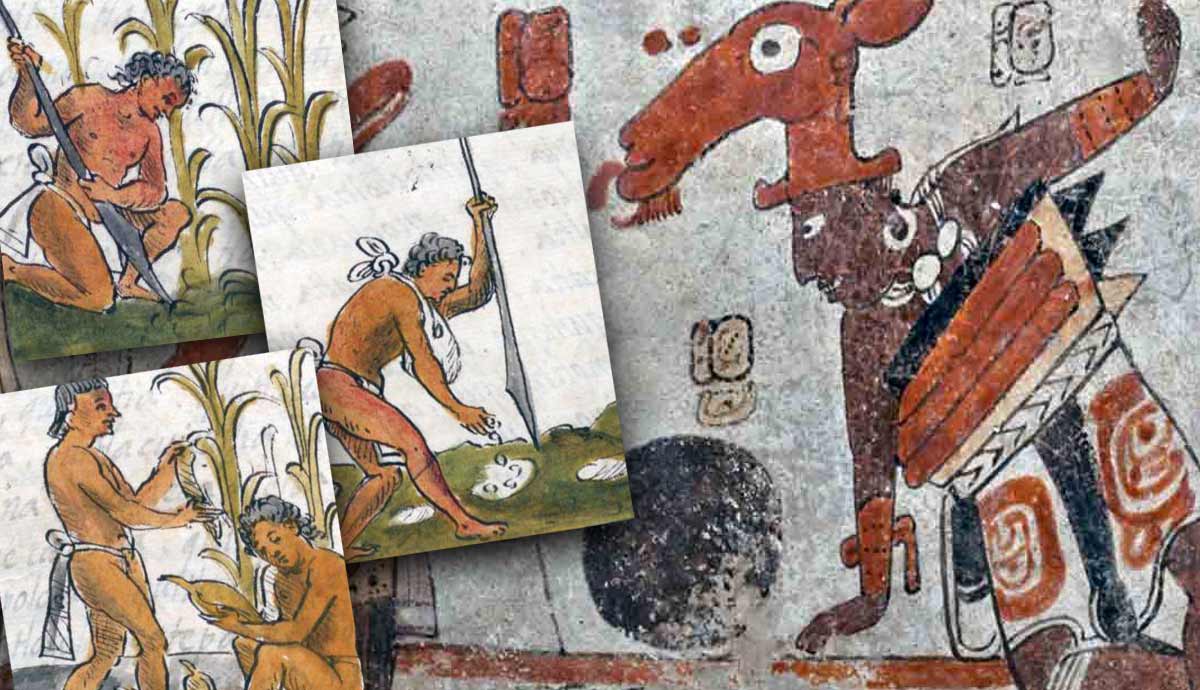

Teosinte, the wild grass that was eventually domesticated into maize, bears little resemblance to today’s corn. The plant had a single “ear” that was teeny by comparison, with just 5-12 hard seeds, not the multiple large cobs full of soft kernels seen today. Fortunately for modern moviegoers, the ancient peoples of Mesoamerica didn’t let the inedibility of corn’s ancestors discourage them. Instead, they invented a tasty snack to tide them over while they worked to cultivate a more edible crop.

Through selective breeding, the Indigenous peoples of present-day Mexico were able to gradually produce a plant with a larger number of softer edible kernels. But before they succeeded in that endeavor, they still had the hard-kernelled predecessors to deal with. Though it was not edible raw, and it was too hard even to grind, they discovered that when heated, pressure would build up in the kernel, leading it to burst. These “popped” kernels were edible and became an important food source that continued to be popular long after a softer, easier-to-use corn was bred.

While it was not the Mexica themselves who “invented” popcorn, but their Indigenous ancestors, Spanish colonizers first encountered popcorn when they invaded the Aztec Empire, where popcorn, or momochitl, was not only eaten but also used in decoration and for ceremonial purposes. In particular, it seems to have been associated with the god of rain, Tlaloc, with popcorn garlands and necklaces worn during festivities to honor him. According to the Spanish chronicle by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, The Festival of Toxcatl, held prior to the rainy season, included women doing a “popcorn dance” to honor the gods and request their blessing in providing essential rains.

5. Fashion-Forward Red Dye

We might not have the bright red color favored by women’s fashion football team uniforms without the Aztec. Before the 16th century, Europeans used a red dye known as madder red, a plant-based dye that made a shade much paler than is common today. The Spanish must have been very impressed when they saw the vibrant scarlet sported by the Aztecs.

The Aztec made their dye from cochineal beetles, which are tiny insects that produce a red pigment called carminic acid as a natural repellent against certain predators. Probably discovering the art around the 2nd century BCE, the Aztec ground up the insects to use them as a natural source of red dye, though it takes 70,000 cochineal insects to produce just one pound of the dye. The Aztec called the pigment “nocheztli,” which means “cactus blood,” reflecting the diet of the insects. They ate the native prickly pear plant, brushing the beetles off the cactus with a deer’s tail.

The Aztec used the dye to color textiles, paint manuscripts, as cosmetics, and even as medicine for issues such as digestive problems and fever. It bonds best with fabrics made from animal fibers, such as alpaca wool, rather than plant fibers like cotton.

The Spanish immediately saw the value of the dye and started to export it to Europe, while protecting the secret of its source to maintain a monopoly. Cochineal dye became central to their economy for three centuries as it was used in the robes of Catholic cardinals and the uniforms of British army officers.

Synthetic dyes capable of producing the same vibrant red were developed in the 19th century, but cochineal is still used as a food dye, thanks to its organic nature.

6. Revolutionizing Rubber

From tires to designer sneakers, rubber is ubiquitous today, and its invention is usually credited to Charles Goodyear. However, the Maya civilization would beg to differ. Ancient Mayans and their predecessors were making and using rubber thousands of years before Mr. Goodyear’s name was first plastered on blimps.

The Maya are famous for their ball courts, and a bouncy rubber ball is key to any ball game. The oldest known rubber ball discovered in Mesoamerica dates to 1600 BCE, meaning the Olmec, a smaller civilization that overlapped with the Maya and is considered one of its predecessors, was likely the first to create rubber. In fact, “Olmec” derives from the Nahuatl word used for this culture that literally translates as “rubber people.”

The Maya continued the practice of ceremonial ball games, making improvements to natural rubber that allowed it to be used in other applications as well, including shoes. By the time the Spanish arrived, a large rubber industry was thriving in the Americas, producing thousands of rubber balls each year, as well as other goods.

The natural rubber first used by the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica came from the Castilla elastica, or Panama rubber tree. In its original state, the sap, or latex, from the tree is sticky and becomes brittle as it hardens; not an ideal substance for bouncy balls. This sap was mixed with juice from the morning glory vine, which created a more usable and bouncy rubber.

Modern researchers have recreated this original Maya recipe, as noted by Spanish chroniclers, and found that adjusting the ratio of latex to juice creates rubber of varying properties, including a less bouncy, more durable rubber that may have been used for shoes. Spanish records from the 16th century indicate that natives were wearing sandals with rubber soles, though no archaeological evidence of ancient flip-flops has been found.

Charles Goodyear, the so-called inventor of vulcanized rubber, created it by heating latex from Brazilian rubber trees with sulfur, which makes the latex more durable and elastic. Interestingly, the morning glory juice used by the Maya to create rubber has sulfur-containing amino acids. The Maya and their predecessors may not have understood the chemistry of polymer chains, but they were still the masters of vulcanizing rubber.

7. Spearheads of Spectator Stadiums

Largest ball court in Mesoamerica, Chichen Itza, Yucatán, Mexico. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The rubber ball games played by the Maya were just as popular with the public as soccer is in that region of the world today. It was also not just played by the Maya, but throughout Mesoamerica, again, just like soccer.

Naturally, people needed a place to play and watch, and so every city in the Maya civilization had a ball court consisting of a playing field enclosed by viewing platforms where spectators could watch the game. While the Maya ball courts may not have rivaled the Roman Colosseum for size and capacity, it is their ubiquity that is impressive. At the site of Chichen Itza alone, archaeology reveals seven ball courts for a population of 35-50,000 people. Today, London has 21 stadiums for a population of nine million.

The stadiums were open-ended and marked by two long, parallel, range-type mounds that have an approximate north-south long axis, forming an I shape. Two vertical stone hoops on the walls of the court stood opposite each other in the center of the long alley. There were sloping benches on either side of the alley, which formed part of the gameplay with the bouncy rubber ball bouncing off the sides. The largest known court was 300 feet long, but courts were not uniform in size.

While ball games were known to have had religious and ceremonial meaning, they were also played for entertainment purposes, and there is evidence of amateur games and even pickup games serving as regular entertainment. In the game Pok-ta-pok, the two opposing sides had to try and hit the ball into one of the two stone hoops, but they could only pass and shoot the ball using their thighs and hips. While it sounds a lot like modern soccer, there is evidence that the losers, at least during ritual games. were sometimes given to the gods as blood sacrifices.

8. The World’s First Chocolatiers

The sweet treat that now marks nearly every holiday celebration has been adapted and, arguably, improved by numerous inventors and companies over the last 500 or so years. But every Hershey’s Kiss and M&M owes its existence to the Maya.

While the English word for chocolate most likely comes from the Nahuatl xocolatl, and it was the Aztec ruler Montezuma whom the Spanish discovered consuming the bitter beverage, it was the Maya and their predecessors who first invented the way to make cacao beans edible.

Researchers believe cacao beans may have been consumed as early as 1500 BCE, and cooking artifacts from the pre-Maya Olmec civilization have shown traces of theobromine, a chemical unique to cacao, and the one that makes it poisonous to dogs!

How they discovered the joys of chocolate is largely a mystery, as in their raw form, the beans are inedible. The process of making them into something people actually enjoy consuming is laborious. Once extracted from the cacao pods, the seeds must first be fermented, then allowed to dry, then roasted, and then finally ground.

The Olmec civilization died out around 350 BCE, but the Maya picked up where they left off, and much more is known about their love affair with chocolate. Maya written records, as well as paintings, carvings, and other artifacts, indicate that chocolate held an important role in society. It was used in celebrations and ceremonies, and the beans served as a form of currency. The word cacao itself comes from the Maya word kakaw, and evidence suggests the Maya were actively cultivating cacao trees, not simply harvesting wild beans.

Chocolate during the time of the Maya civilization was not usually sweetened, but was popular and widely consumed. Despite its bitter flavor it was enjoyed as a hot frothy beverage, chocolhaa, and sometimes spiced with ground chilis, cinnamon, vanilla, or other herbs.

What chocolate wasn’t to the Maya was food. It was always a beverage. Treats like truffles and candy bars came long after the conquest by the Spanish, who shared the treat with Europe, and hundreds of sweet goodies were developed, all from the humble Maya kakaw bean.