From the pre-Christian heroic age to the arrival of the Vikings in the late 8th century, Irish kings were almost constantly at war with each other. At stake were both the material and symbolic accouterments of status that would allow them to dominate their neighbors.

The most powerful of these kings would claim the title of “High King of Ireland,” usually equated with the kingship of Tara. Yet adopting a highfalutin style did not make it so. One of the few consistent things about a king’s power within this loose system of overlordship was that it almost never outlasted the individual whose personal gravitas had paved the way for them to claim such a position. A profound lack of centralization, coupled with the effective absence of any organs of government, made for a true political free-for-all in Early Medieval Ireland.

Irish Society During the Early Medieval Period

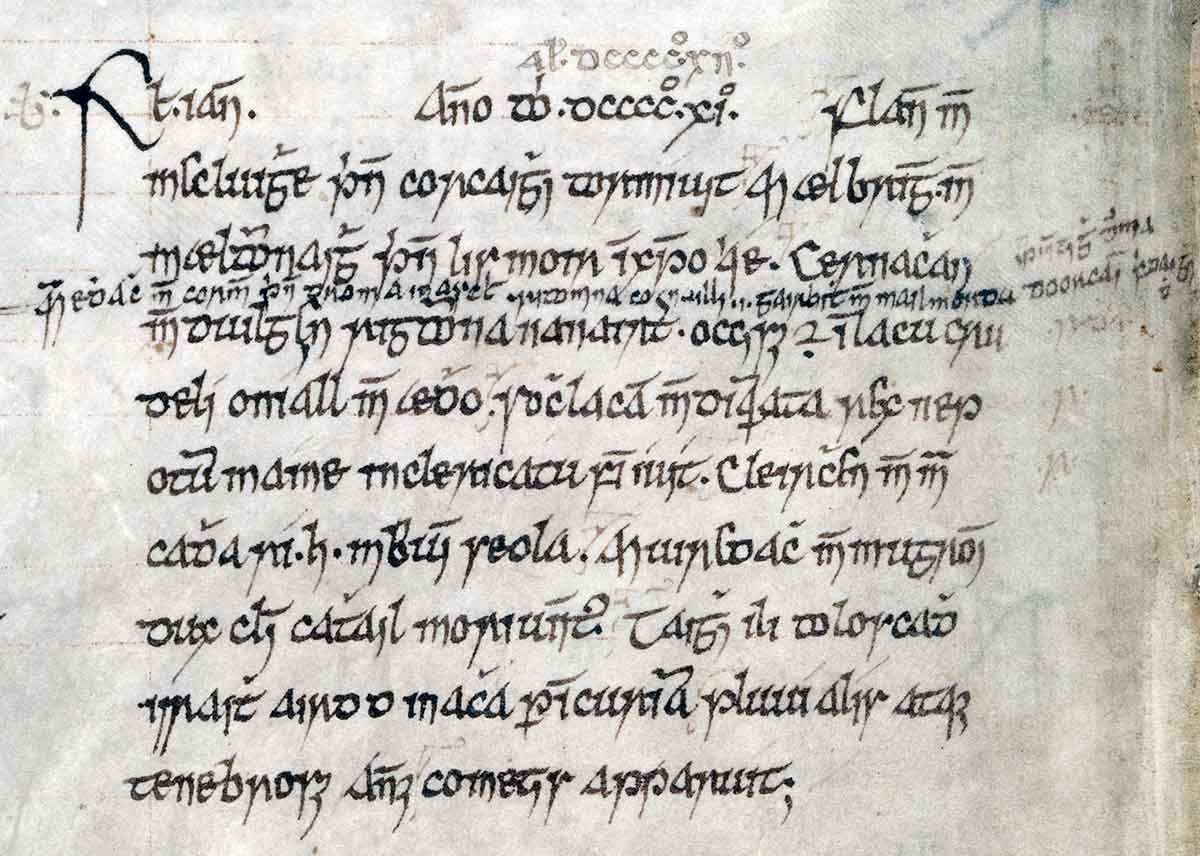

We are arguably better informed about the nature of society in early medieval Ireland than in almost any other part of Europe. The arrival of St Patrick, and thus of Christianity, in Ireland is dated to 432 CE by the Irish annals. Although this date is thought to be artificially early by historians, who espouse the so-called “two Patricks theory,” and see this retrospective editing of history as part of an effort to discredit the efforts of other missionaries such as Palladius. Most scholars agree that the historical St Patrick had probably arrived in Ireland by the late 5th century. Thus, Ireland began its conversion to Christianity well over a century before the arrival of Augustine in England in 597, and it was largely achieved by this date. The Annals of Ulster, record St Columba’s arrival on Iona, and his foundation of a monastery there, under the year 563.

The implications of this are significant. Ireland was to develop monasteries, libraries, and scriptoria (writing rooms where illuminated manuscripts were produced) to support a budding literate culture long before the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. As such, there is a proliferation of chronicles, annals (year-by-year records of significant events), saints’ lives, and legal texts that can tell us much about Irish society from as early as the 6th century.

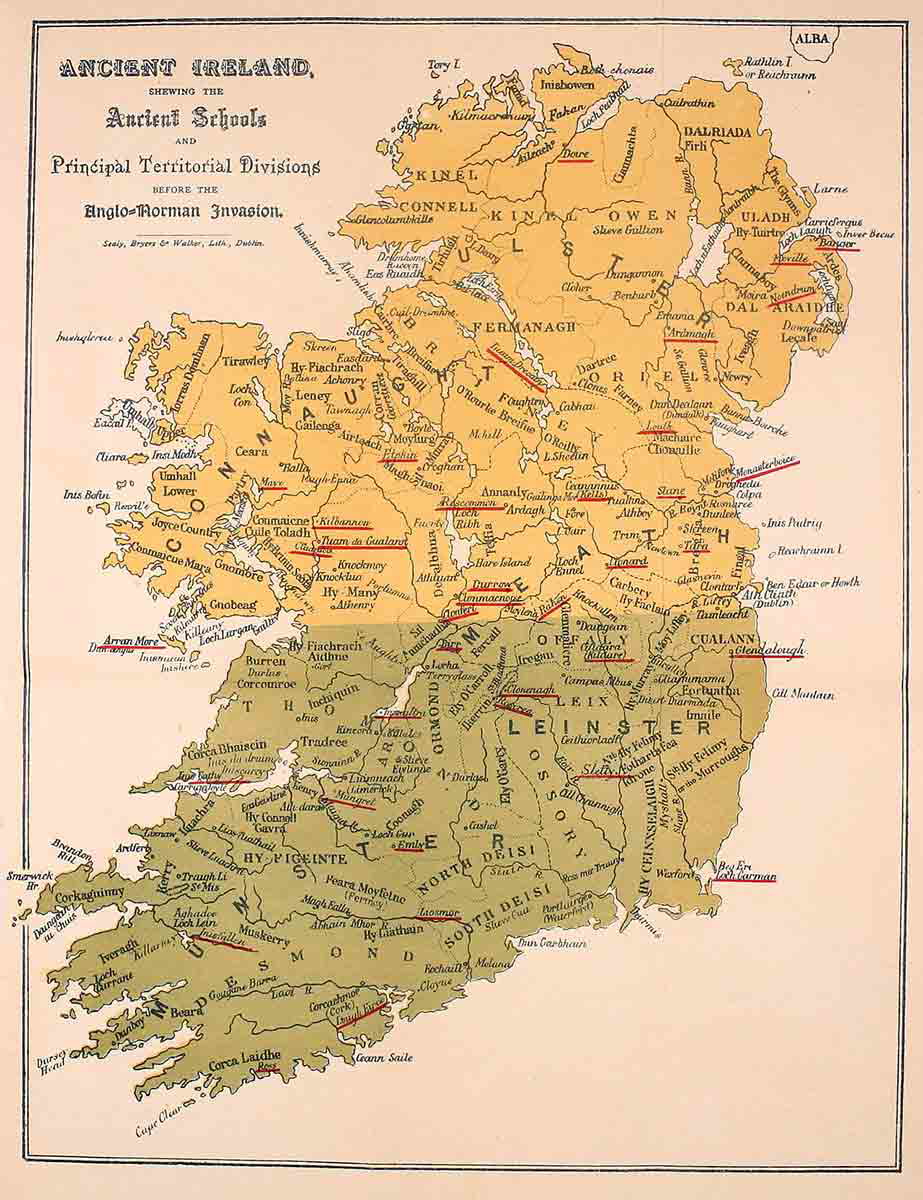

What emerges from these written sources is that Ireland in the Early Medieval Period was an immensely complex tapestry of different kingdoms and sub-kingdoms, constantly forming and reforming into new constellations. The fundamental socio-political unit here was the túath (pl. túatha), meaning “people” in Old Irish. Although there are varying interpretations of the precise semantics of the word, Thomas Charles-Edwards, one of the leading historians of medieval Ireland, defined it essentially as “preeminently a community of farmers” as well as “the domain of public acts.” If searching for an analog from the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, we would probably find it either in the “hundred” or the “shire,” discrete territorial groupings with their own self-contained legal jurisdictions.

It seems to have been very common for túatha to combine into larger polities under more powerful kings, who in turn might compete with each other for the kingship of a larger kingdom comprising most or all of what we would call a province, such as Ulster or Meath, the largest political unit. The five provinces of Ireland, in fact, owe much to the geopolitics of these early Irish conflicts.

These three levels of kingship, each of which was broadly within the range of normalcy at any one time, are reflected in 7th-century Irish laws. The text Crith Gablach (a text on status) describes three ranks of king: rí ruirech (king of great kings), rí buiden (a king of war bands), and rí túathe (a king of a people). If there is even a degree of veracity to this idealized hierarchy of power, Ireland was truly a country bursting at the seams with kings.

Inextricable from the túath was the kinship group, or fine, which was arguably the main basis for kingly legitimacy in early medieval Ireland. The view of kinship that we get from the sources is arguably somewhat skewed since it was vulnerable to tampering by later scholars who wished to legitimize dynasties by associating them, fictitiously, with a famous historical ancestor such as Niall “of the Nine Hostages.” Within a kinship group such as the Uí Neill, the alleged descendants of Niall, there were several sub-groups each ruling over their own túatha.

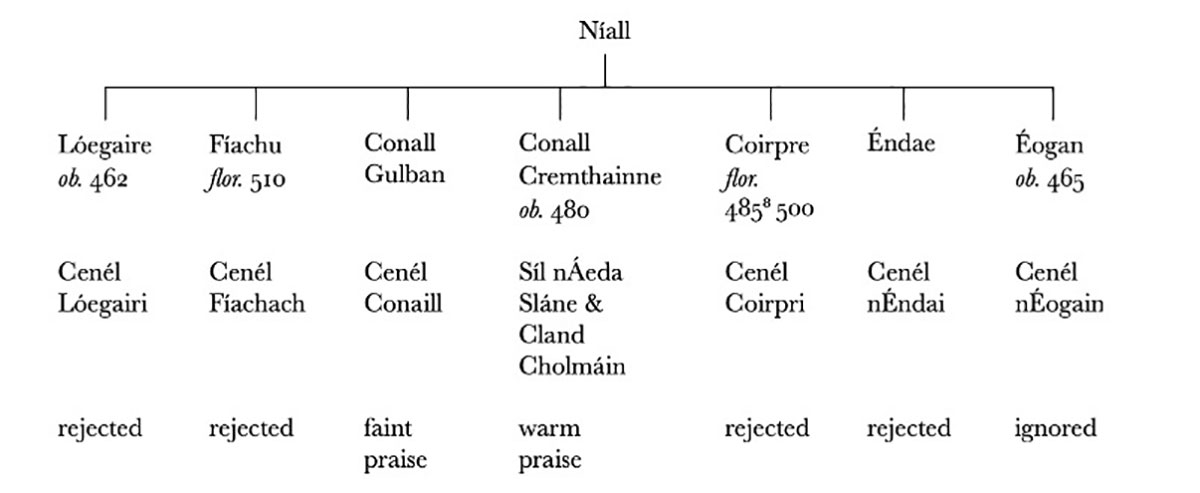

In Meath, dominated by the “southern” Uí Neill, there were six branches of the dynasty competing for power and status: Cenél nÉndai, Cenél Coirpri, Cenél Lóegaire, Clann Cholmáin, Síl nÁedo Sláine, and Cenél Fiachach. Each of these ruled over their own túath and would compete to dominate the túatha around them. The most powerful among these could then hope to lay claim to the kingship of Meath. The northern Uí Neill dynasties, the Cenél nEógain and the Cenél Conaill would similarly compete for power in Ailech, in the far north of Ireland.

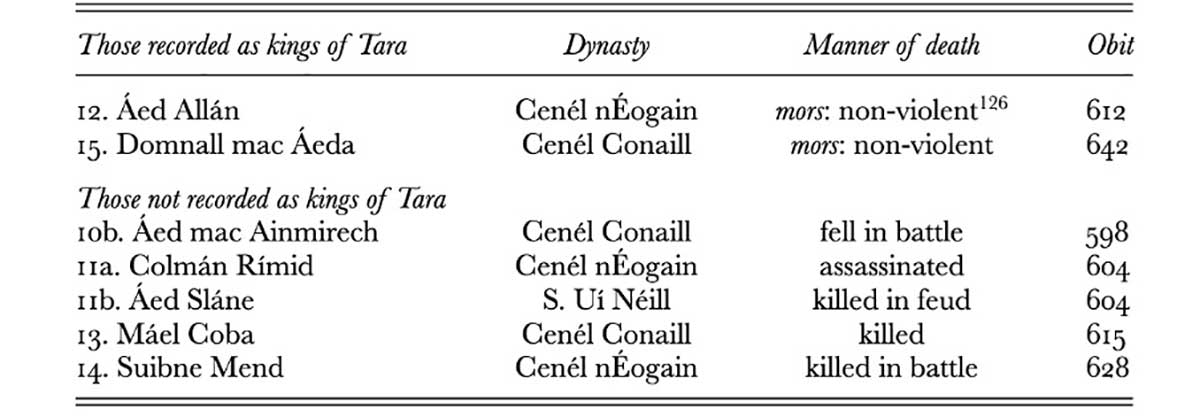

While kings were consistently able to project power over an entire province and thus become ri ruirech, it was more unusual to obtain overlordship over other provinces. Certain exceptional figures, such as Áed Allán from the northern Cenél nEógain Dynasty in the 8th century, were able to dominate other kingdoms. The most powerful kings among the Uí Neill could lay claim to the kingship of Tara, denoting kingship over all of the Uí Neill kindreds and túatha in both the north of Ireland and in Meath.

Even rarer was a king that could project power over the two “halves” of Ireland, Leth Cuinn (“Conn’s half,” the provinces of Meath, Ulster and Connacht) and Leth Moga (“Mug’s half,” the provinces of Leinster and Munster). No king was in fact able to do this until the later 9th century.

In the contest for power in Ireland, titles and styles were important. Ireland was a land that put a lot of stock in symbolism and sacred places such as Tara, which was central to the Uí Neill kindreds’ own power. The polities cobbled together by Irish kings were never two of the same, and kingship was based both on control over territory and other kin groups. But how did kings compete for power in early medieval Ireland, and what constituted power?

Irish Warfare in the 5th to 9th Centuries

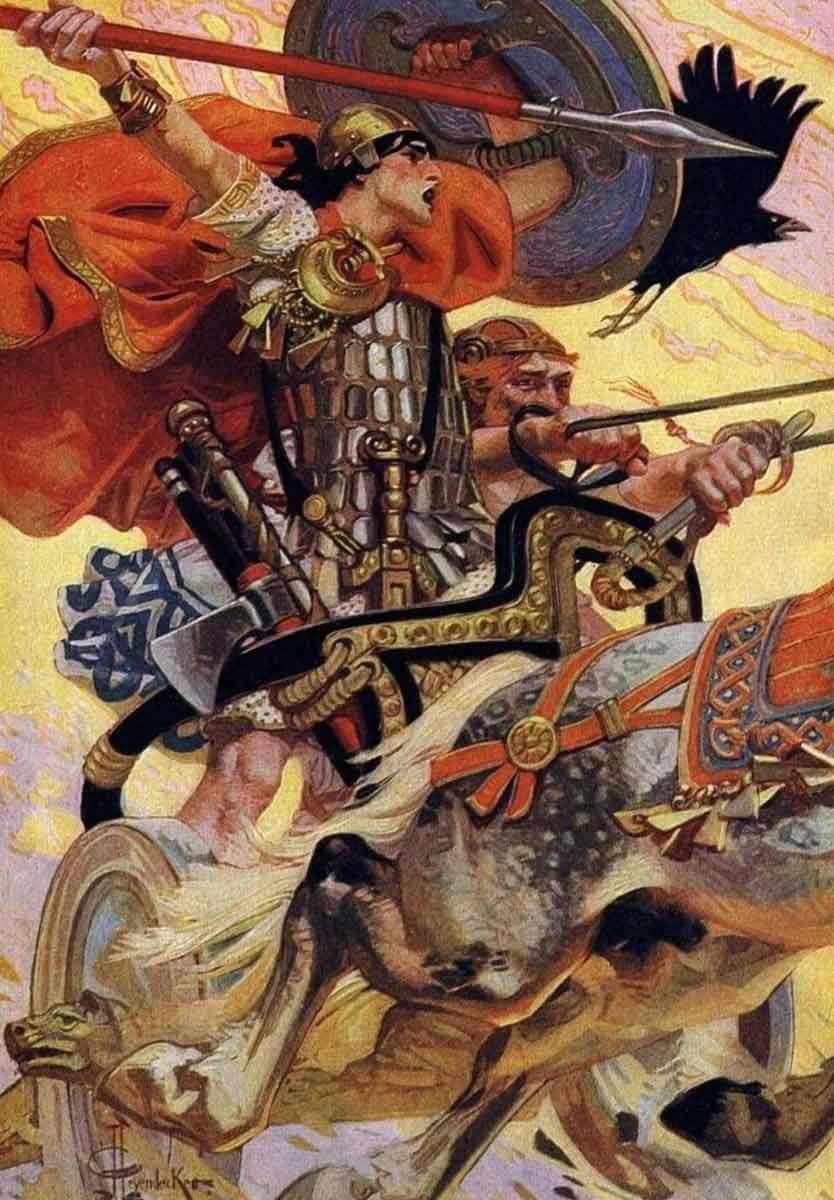

Early Irish literature, chiefly the so-called “Ulster Cycle,” paints early Christian Ireland as a war-torn land wracked with feuds and dominated by heroes. Some of the stories contained in the Ulster Cycle are no less dramatic, or tragic than what we find in the great Greek epics.

One episode, from The Death of Aife’s Only Son, sees the hero of the Ulster cycle, Cú Chulainn, slay his own son Connla, who had come to Ulster after having pledged to his mother Aife not to reveal his identity, nor ever to back down from a challenge. Another famous epic from the Ulster Cycle is the so-called Cattle Raid of Cooley, in which Queen Medb of Connacht invades Ulster, seeking out the precious stud bull, Donn Cúailnge. Cu Chulainn defends Ulster single-handedly, killing hundreds of his opponents, each in single combat, which eventually forces Queen Medb to retreat.

The Ulster Cycle is useful insofar as it reflects how people in early medieval Ireland conceptualized a heroic past in light of their own experience. No doubt warfare was somewhat more prosaic than the tales of individual prowess and heroism in the Tain suggest. Yet the Ulster Cycle puts some rather fanciful flesh on a skeleton of truth. Cattle raiding was indeed a key element in the power play between petty kings in early medieval Ireland. The first reference to cattle raiding in Irish chronicles comes in 628, and there are numerous references thereafter.

The Annals of Ulster entry for 721, for instance, describes “An invasion of the Laigin (men of Leinster) by Fergal,” and that “the cattle-tribute was imposed and the hostages of the Laigin secured for Fergal son of Mael Dúin.” As difficult as these laconic entries can be to decipher, the impression we get from the sources is of a world of hit-and-run raids for wealth in cattle and kind. The ring-forts which are so ubiquitous in the Irish landscape are undoubtedly a reflection of widespread cattle raiding, and the need of ordinary farmers to protect themselves from it on a smaller scale.

While Irish warfare may not have been as glorious as the epics suggest, there seems little reason to doubt that kings fought alongside their fían, or warband, in the thick of the fighting. The Irish annals are full of references to Irish kings dying in battle, to the extent that they form a large part of the subject matter. From this, it may be inferred that battles involved relatively small armies. In order to conduct lightning raids, armed forces needed to be mobile, and to retreat quickly into friendly territory with their bounty.

The nature of warfare as a small-scale, individualistic affair would also go a long way toward explaining the frequency of violent deaths in battle of kings, who might have been better able to protect themselves from danger had they been in command of larger military forces.

There seems little reason to doubt, furthermore, that Irish armies were poorly armored, or not at all. The settlement of the Vikings in the 9th century brought urbanization and the production of armaments, including hauberks, or coats of mail. The importance attached to these items by later texts such as the Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh, which singles out the Vikings for their use of heavy armor, suggests that chainmail was rare before the arrival of the Vikings in Ireland.

Raiding for cattle was important since there was no coinage in Ireland at this time, and silver, in general, was relatively rare before the Viking Age, when Scandinavian raiders and traders brought Ireland within a network of long-distance trade stretching to the shores of the Caspian Sea, bringing exotic goods with them. Precious metals seem only to have been used for very high-status items, such as the Tara Brooch, before this. Nor is there any evidence for fortifications of the type that would allow armies to dominate the landscape, as Edward the Elder and Æthelflaed were able to do against the Vikings during the unification of Anglo-Saxon England. Neither the Irish ráths nor the symbolic hillfort sites such as Tara, show any evidence of having been used in this way.

Without defensible positions from which to hold down territory, or a source of wealth which could store value and itself could be easily stored and protected, it was almost impossible to establish any kind of consolidated political advantage. There is no doubt that this explains, in large part, the interminable violence, and the pattern of raid and counter-raid, which characterized kingly politics in early medieval Ireland.

Institutions of Kingship

On what then, did the power of ambitious Irish kings rest, aside from the pattern of cattle-raiding and battles recounted by the annals, and embellished by the epics? The evidence of the annals gives us a few scraps of information in this regard.

Both the Annals of Ulster and historical texts connected with St Patrick written at Armagh make reference to an event known as the “Feast of Tara.” This was the site for one of the confrontations between Lóegaire, one of the supposed sons of Niall “of the Nine Hostages,” and St Patrick, at which various texts recount Lóegaire as having plotted the death of Patrick and having been foiled by the saint. The Life of St Patrick by Muirchú places at the Feast of Tara alongside Lóegaire “the kings, satraps, leaders, princes and the nobles of the people; also the druids, incantators, fortune-tellers, and the inventors and teachers of every skill and craft.”

Although little can be gleaned from the sources about the nature of this event, it seems likely that the Feast served as an occasion for sub-kings to renew their allegiances to the king of Tara, and perhaps for gift-giving and the formation of new political alliances. The nature of the Feast as a pagan festival is supported by the annals, which record the last instance of the Feast of Tara in 560, by which time the conversion of Ireland to Christianity was mostly complete. Yet Tara continued to be an important site, playing host to an important ecclesiastical synod in 780 between the men of the Uí Neill and Leinster.

Tara was not the only important royal site in Ireland during the Early Medieval Period. The Rock of Cashel, sometimes known as Cashel of the Kings in the Irish annals, was the symbolic site associated with the kings of Munster. Emain Macha in Ulster was also a pagan site until the 4th century and was probably an important center associated with the kings of Ulaid during the following centuries. The Grianán of Ailech was the royal site contested by the northern Uí Neill kindreds and was an altogether more impressive spectacle with a five-meter-high (16-foot) ring stone wall, probably built during the 8th century, crowning a prominent hill in Co. Donegal.

What all these sites have in common is a long history stretching back into the early Iron Age, and even in some cases going back to the Neolithic Period. Association with a site of such antiquity must have endowed the king in question with a degree of legitimacy, a sense that their dynasty too had an ancient claim to power and authority. It is not unlikely that Irish kings held regular assemblies here at which their vassals, and sub-kings from further afield, attended.

Another ceremonial event associated with the Uí Neill kings was the so-called Oenach Tailten (“Fair of Teltown”). The Annals of Ulster, with its characteristic aversion to expanding on details, describes under the year 717 a “Disturbance of the fair of Tailtiu by Fogartach, in which Ruba’s son and Dub Sléibe’s son fell.” The Fair of Teltown seems to have been held regularly right up to the Norman Invasion of Ireland in 1171. The nature of the occasion, unfortunately, remains shrouded in mystery.

Some modern Irish observers conceptualize the event as a kind of Gaelic Olympics, endowing it with a history that reaches far back into the prehistoric past. Whatever the truth of the matter, it is likely that the Fair of Teltown was primarily an occasion for forging alliances and for the visual demonstration of status and munificence on the part of the king of Meath. It may also have served as an opportunity for traders to flaunt their wares to assembled guests, and for the latter to exchange the latest rumors and gossip. The disturbance of such a fair constituted an affront to the royal dignity, a challenge that any presiding king must have had to meet with punitive justice in sight of their dependents.

Slender as the evidence may be, it seems that there was some limited institutional underpinning to the power of Irish kings. The association with ceremonial sites, often centuries-old already by the time of St Patrick’s arrival in Ireland, enabled kings to claim a legitimacy that periodic feasts, fairs, and assemblies may have served to reify and enhance.

The Role of the Church

The influence of the Church can only have added to this sense that some dynasties in particular were singled out for greatness. The history, and pseudo-history, of St Patrick was a convenient device in this regard. During the 7th century, the Church of Armagh lay claim to the heritage of St Patrick as a means of legitimizing its primacy among the churches of Ireland. St Patrick’s own writings, the Confessio, and the Epistola, make no reference to Armagh, but two later scholars, Muirchú and Tírechán, both sought to realign Patick’s missionary itinerary through Ireland to give pride of place to Armagh.

Irish scholars’ predilection for tampering with their own history was not confined to the world of the Church, however. Muirchú and Tírechán both frame Patrick’s conversion of Ireland partially as a sequence of encounters with various progenitors of Uí Neill dynasties. Patrick is said to prophesy a glorious future for certain branches of the family and to condemn others to obscurity. Clann Cholmáin from the southern Uí Neill, and Cenél Conaill from the northern Uí Neill, were singled out in particular for greatness, while other branches of the family such as Cenél Fiachach and Cenél Coirpri, were rejected. Yet other famous branches, such as the Cenél nÉogain, were ignored and may only have claimed kinship with the other Uí Neill dynasties later.

Comparing this with the evidence of the Irish annals, what emerges is that the kindreds “favored” by St Patrick were, in fact, the predominant dynasties of the 7th and 8th centuries, not those who ruled during the 5th and 6th centuries, when St Patrick is thought to have been active. It is a clear case of history being written, or commissioned, by the victors.

Those branches of the Uí Neill who were best able to patronize the Church of Armagh were to receive a return on their investment: blessing and legitimation from Ireland’s principal saint interpolated into the church’s historical traditions. Historical contingency became historical destiny, and the ascendant kinship groups were given the legitimacy of a value and apparent antiquity no less compelling than that conferred by their association with ancient hillforts.

How to Become a King in Early Medieval Ireland

Thus far we have dealt with kinship groups, and their legitimacy in providing kings of larger political units, such as the provinces of Meath or Ulster. But how to choose a king from among the ranks of a kinship group? If the origin of the various branches of the Uí Neill lies in the pseudo-historical mists of the 5th century, then by the 7th and 8th centuries there would have been scores, potentially hundreds, of eligible candidates for the kingship of a túath such as that controlled by Cenél Conaill in the southern Uí Neill territories.

The central concept for determining candidature for kingship was febas, or “personal excellence.” The greater part of this had to do with descent, both in the male and female line. A successful candidate needed to have had either a father, grandfather, or great-grandfather who had been king. If all three had been kings, he would be in a very strong position.

High-status relatives on the maternal side, such as kings of the same túatha or a neighboring one, both alive and dead, could also provide claimants with an edge over their rivals. Those possessing the requisite royal lineage were known as rígdamnae, or “royal material.” There is a strong parallel here between early medieval Ireland and Anglo-Saxon England, where the term ætheling denoted “throne-worthiness,” not any kind of special status as the king’s chosen heir.

Aside from this, the sources offer tantalizing hints of the personal qualities involved in laying claim to the kingship of a túath, or a larger political unit such as a province. This is clearest in the case of an extraordinary sequence of events, when a potentate from outside the Uí Neill kindreds, Congal Cáech of the Cruithni in Ulaid, laid claim to the kingship of Tara in the 630s.

In 628, Congal had defeated and slain Suibne Menn of Cenél nEógain, who himself had taken power by slaying his rival Máel Coba from Cenél Conaill twelve years previously. A most unlikely source, the Bechbretha, a legal tract on beekeeping, gives us a fascinating incidental detail about Congal Cáech, recounting how he was blinded after being stung in the eye by a bee owned by his rival for the kingship of Tara, Domnall mac Áedo. His partial blindness, a physical blemish, apparently disqualified Congal for the kingship, although he was still trying to reclaim it in 637 when he was slain in the Battle of Mag Rath, against Domnall.

There is again, here, a likely discrepancy between the written sources, especially legalistic ones, which presented a somewhat idealized version of how royal succession worked in Ireland, and the historical reality. Congal Cáech’s continued efforts to claim the kingship of Tara suggest that his physical blemish, his loss of “face” in a quite literal sense, did not relegate him to the wings of the political stage. The violent deaths of Suibne Menn and Máel Coba, who were probably both killed in ambushes, also suggest that a claimant’s acquisition of kingship did not mean that other eligible dynasts, from their own or other dynasties, would lie down and accept the new status quo as they saw it.

We hear mostly of contests for power at the highest level, particularly for the kingship of Tara, but it is interesting to hypothesize that at the level of the túath, similar ruthlessness may have been the norm as well. The demands of royal succession at all levels may have served to prune the family tree of each kinship group on a regular basis.

To be a king, or even a strong candidate for kingship, in medieval Ireland, was to dramatically increase your chance of a sword in the back or a spear in the belly. Despite their ability to win hearts and minds, neither clever historiographical airbrushing nor feasts amid crumbling hilltop ruins could turn aside the reality of a land full of claimants who could become king by the strength of their sword arm and their capacity for ruthlessness and cunning, even if they could not remain so for long.