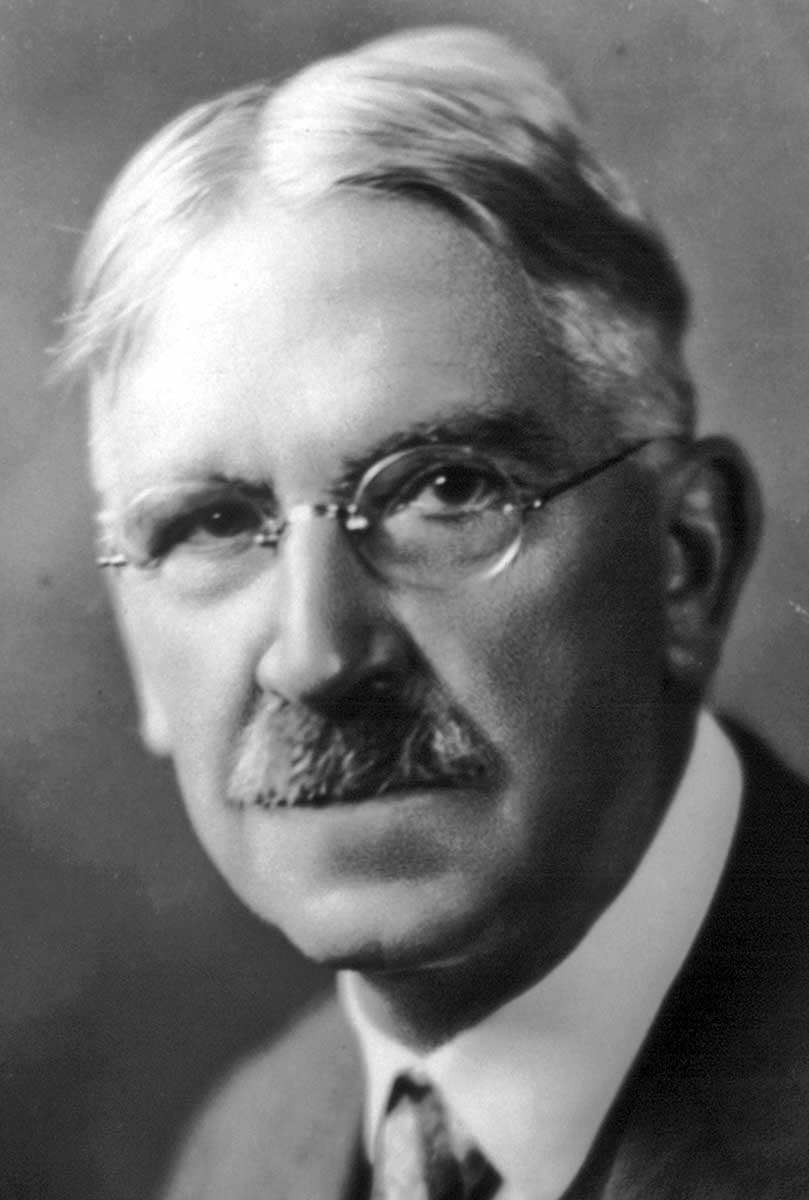

Choosing key ideas from John Dewey’s philosophy is a challenge given that his work fills thirty-seven volumes that he spent over seventy years writing on various topics. This article focuses on five of Dewey’s ideas: his theory of inquiry, instrumentalism, political philosophy, moral philosophy, and philosophy on education. Dewey was labeled as both a philosopher and an educator, which meant he garnered two very different audiences. Although Dewey has occasionally sparked controversy, there is no denying that he was one of America’s most important thinkers in the early 20th century.

1. Theory of Inquiry

Common to other pragmatist thinkers, inquiry was fundamentally central in Dewey’s philosophy. He believed that inquiry was the core of any theory we create about knowledge and the search for what he would call “warranted assertions” rather than “truth.” The role of inquiry is to resolve problems and/or doubts. This is how inquiry proceeds: a problem or doubt arises, for which we have theories, but which might be revised as we gain new insights via the scientific methodology we use to work through the issue. Our aim in this process is to obtain the “warranted assertibility” of the resolution of that problem in a new or newly-refined settled belief. There is also an important connection to biology here for Dewey: the motivation behind this process is to achieve a state of stability and harmony.

But as is commonly misconstrued about pragmatism more generally, this is not an anything-goes position. Another important part of our motivation with inquiry is our desire not just to solve problems, but to get things right. Still, what we should expect to obtain is security rather than certainty, at least most of the time. We want reliable solutions that follow the evidence; the solutions satisfy the needs of not just the inquirer, but the inquirer’s environment as well. And like some, but not all, individuals labeled “pragmatists,” there is no separation between subject and object. We are always inquirers inextricably tied to our environments.

2. Instrumentalism

No thinker labeled “pragmatist” took on that term whole-heartedly. None of them were quite sure that this was the best word to describe their methods, all of which had relevant differences as well. In the case of John Dewey, when applying that term, perhaps it is best to do so by describing his work as “pragmatic” in nature rather than as “pragmatism.” However, Dewey generally referred to his method as “instrumentalism.” His is a process philosophy; our ideas and beliefs are instruments for achieving some end. This means that we live in a world that makes demands on us, and we must respond. When presented with doubts and problems, we must think about how to resolve them within the context of our personal, social, and environmental lives. Inquiry involves confusion and resolution. Inquiry is forward-looking because the eventual warranted assertions we arrive at require a process of verification in the future.

As a “process philosophy,” inquiry never ends. We are constantly confronting doubts and problems that need resolving. Our theories need to be frequently adjusted when, as instruments, they no longer work as they once did. When we have an inquiry, it presupposes that there is an answer and that we can go out and verify it. Thus, an inquiry warrants an assertion. Presumably the aforementioned assertion is warranted by inquiry, which then resolves the problematic situation that gave rise to that inquiry—this process is always inextricably interconnected in this way in Dewey’s philosophy.

3. Political Philosophy

For Dewey, everything is bound up with his theory of inquiry; this is where everything starts, including politics. As we have seen, his theory of inquiry proceeds as follows: a practical problem arises, for which we have theories. These theories might be revised as we gain new insights via the scientific methodology we use to solve the problem. Democracy is arguably such a process by its very nature. Democracy is a collaborative effort in this endeavor. This idea is tied to Dewey’s moral philosophy since democracy is a community of inquirers working to achieve a communal society that is harmonious and stable. The needs of all those within the community are deliberated upon to determine how to achieve the most ideal situation for all involved. Thus, again, problems and doubts, whether about politics or ethics, are resolved, ideally, in this process of inquiry.

Democracy is critical in this process because the beliefs we hold should stand up to all experiences, not just our own. We must consider others because we always live with others. Democracy, then, is just such a collective process. Dewey, as with several other pragmatists, emphasizes meliorism, or the position of warranted assertion: we may not acquire absolute certainty in our beliefs, but we can hopefully acquire reasonable stability and harmony.

4. Moral Philosophy

Dewey’s moral philosophy is arguably more developed than any other pragmatist—perhaps in part because of his long life (he outlived Willam James and Charles Sanders Peirce, for example, by about four decades). Ethics is tied to his theory of inquiry: the same applies to problems and doubts of an ethical nature. Thus, through deliberation in our process of inquiry, we construct meaning with the aim of being better individuals both personally and socially. Dewey focuses on progress and growth rather than end goals. This focus has drawn criticism from others since it does not provide any absolute moral certainties, but it does align more with pragmatist thought.

As inquiry is meant to satisfy the needs of the inquirer and his or her environment, so too should moral judgment. A moral problem(s) or doubt(s) arises, for which we have theories, but which might be revised during our investigation. We think, we reflect, we get more information, we experiment directly or just in our mind, we deliberate over our needs and those of the environment, and we consider if adjustments need to be made. With all of this work we are aiming to be better human beings within society. This process of inquiry is so important because it unveils the value we place on things and needs. Until we engage in this process, we do not know what we value or what is valuable broadly.

5. Philosophy on Education

Humans are problem-solving instruments, and the theories we create, as well as life itself, are essentially experimental. The same applies to education: it must be flexible to the ever-changing world we find ourselves in. Many pragmatists agreed that our general goal should be to improve our lives, both directly and practically. Nothing, argued Dewey, is more effective in this endeavor than education.

As many other important thinkers have argued, Dewey believes we are creatures of habits, and schools exist primarily to cultivate the right habits. Theories on pedagogy require flexibility for adapting to changes that lead to new or altered needs. The best kind of educator is someone like Socrates; an individual who teaches students to think critically, rationally, and logically. Education should focus on cultivating students’ creativity, not rote memorization. Inquiry should be pursued individually, not forced upon others. However, the role of other people is critical as well. In connection with Dewey’s emphasis on democracy, an inquiry must involve taking into consideration as many other perspectives as possible: the good of the whole depends on the good of its parts.

We live in a society, so our particular habits as individuals can overlap with those of our community. The self is a social self that takes on socially-conditioned habits. Those habits create meaning in the world by guiding our actions and producing practical consequences. It is through learning that we create those habits, presented via education. Considering Dewey’s emphasis on experimentation, it was apt that some called the private elementary school he founded an “educational laboratory.” Taking a Darwinian approach, Dewey considered the educator and the student as both ever evolving toward continued success in being better in their roles. The best inquiries will arise to be resolved toward progress. Education is always met with more education.

Dewey had much to say about epistemology, political philosophy, moral philosophy, aesthetics, naturalism, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of education, to name some of his areas of concentration. While some charge that he left some topics unclear or unfinished, despite the plethora of work he produced, this nonetheless is consistent with pragmatism; with the task of their philosophy being to produce a method that aims to make life better, but that is an unceasing process. Thus, one might surmise that the meaning of life for this kind of pragmatist is to continually make more meaning, and this is why education is of fundamental importance; philosophy is an inquiry into education, primarily.