The Arthurian legends do not often talk about King Arthur’s brothers. Most of the time, Arthur is presented as the only son of his parents, although he does often have sisters. However, even in the case of his sisters, Morgause and Morgan le Fay, these are most famously presented as his older half-sisters, with Arthur being the only child of Igerna and Uther. Nevertheless, there are some obscure texts which do provide Arthur with brothers. In this article, we will examine what we know about these obscure figures from the Arthurian legends.

Madoc ap Uthyr: Madoc Son of Uther

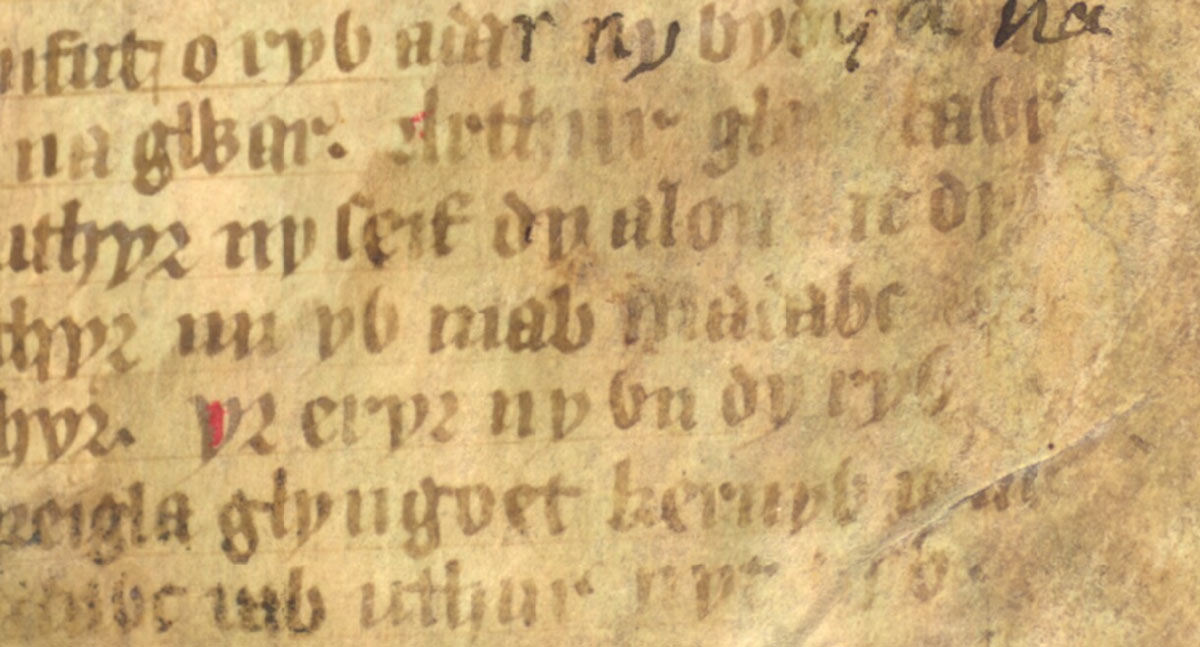

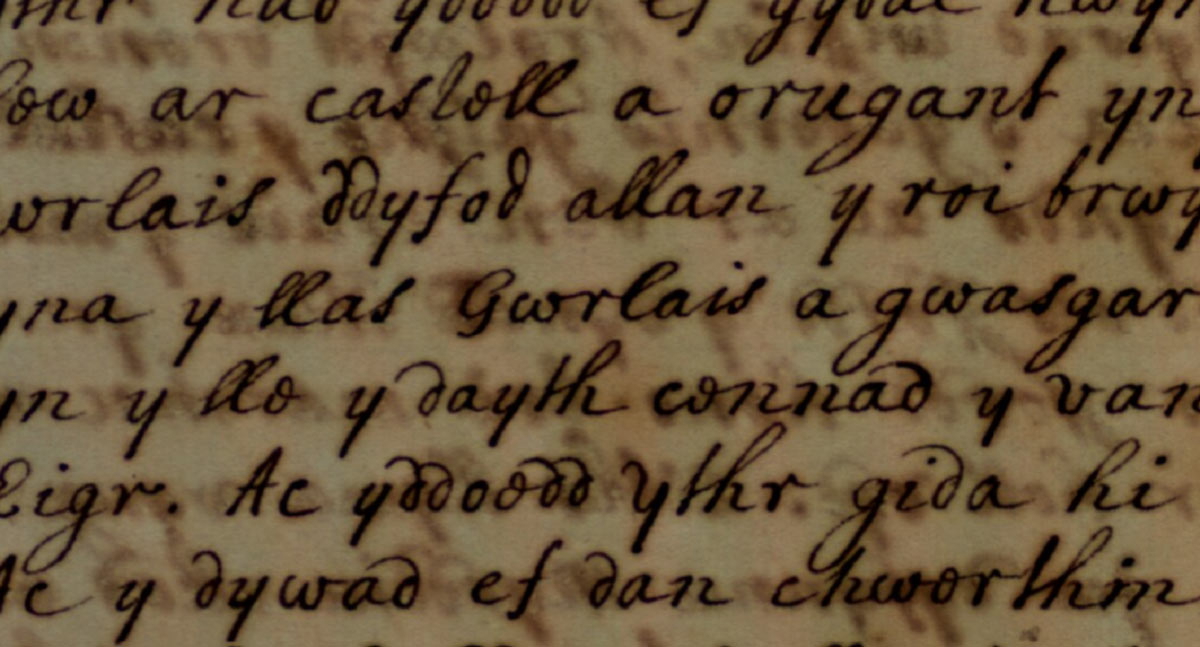

The very earliest source that mentions a brother of King Arthur is a poem entitled Madawg drut ac Erof, which dates to roughly the 9th to 11th century. Incidentally, this date would also make it one of the earliest Arthurian sources. This poem, which is found in the Book of Taliesin, is an elegy or death song dedicated to a figure known as Madoc ap Uthyr. His name is also written as Madog or even Madawg. The Uthyr mentioned as his father is evidently the Uthyr Pendragon of Arthurian tradition.

This is confirmed by a later poem, dated to c. 1150 at the earliest, usually known as Arthur and the Eagle. This presents a conversation between King Arthur and the spirit of his nephew, Eliwlod, who appears to Arthur in the form of an eagle. They have a conversation in which his nephew educates Arthur on religious matters. The nephew is called the son of Madoc ap Uthyr, confirming that Madoc’s father, Uthyr, is identical to Arthur’s father by that same name.

Not much is known about Madoc. Aside from his elegy and the poem involving his nephew, there are only a few isolated references to him in Welsh poetry, none of which provide useful information. The single most useful source is his grave elegy, which provides us with a brief overview of who he was.

The opening of the elegy strongly implies that Madoc had a position of power, being a ruler of some kind. However, the poem focuses on Madoc’s downfall. It refers to his downfall being caused by a certain “Erof,” whose identity is unclear. It is possible that this is a name given to some kind of natural disaster since the poem refers to the earth quaking and a shadow falling on the world. Furthermore, an adjacent poem in the Book of Taliesin refers to Erof in its title, and the poem itself refers to its subject in apocalyptic terms. Still, very little is known for sure about who or what Erof was and how exactly he, or it, caused Madoc’s downfall.

The Curious Case of Gormant ap Ricca

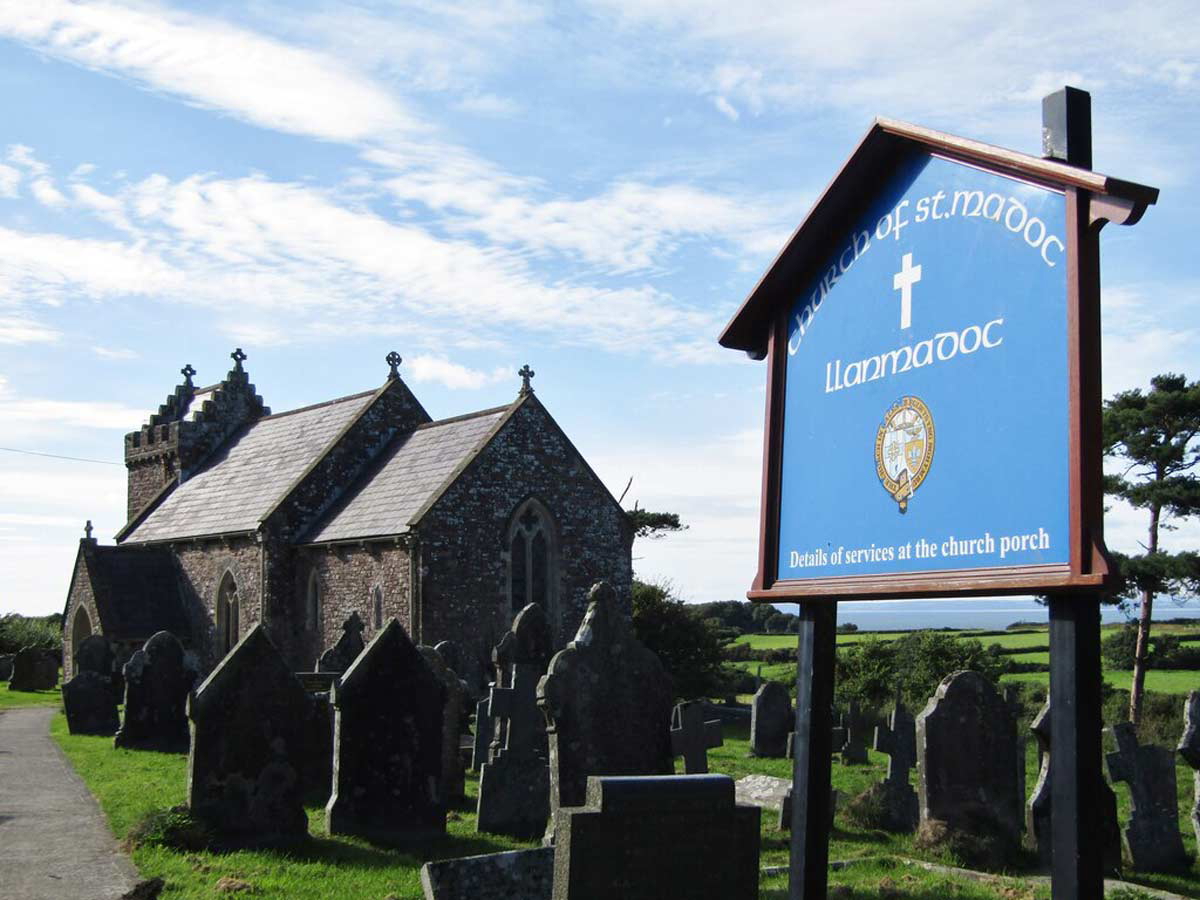

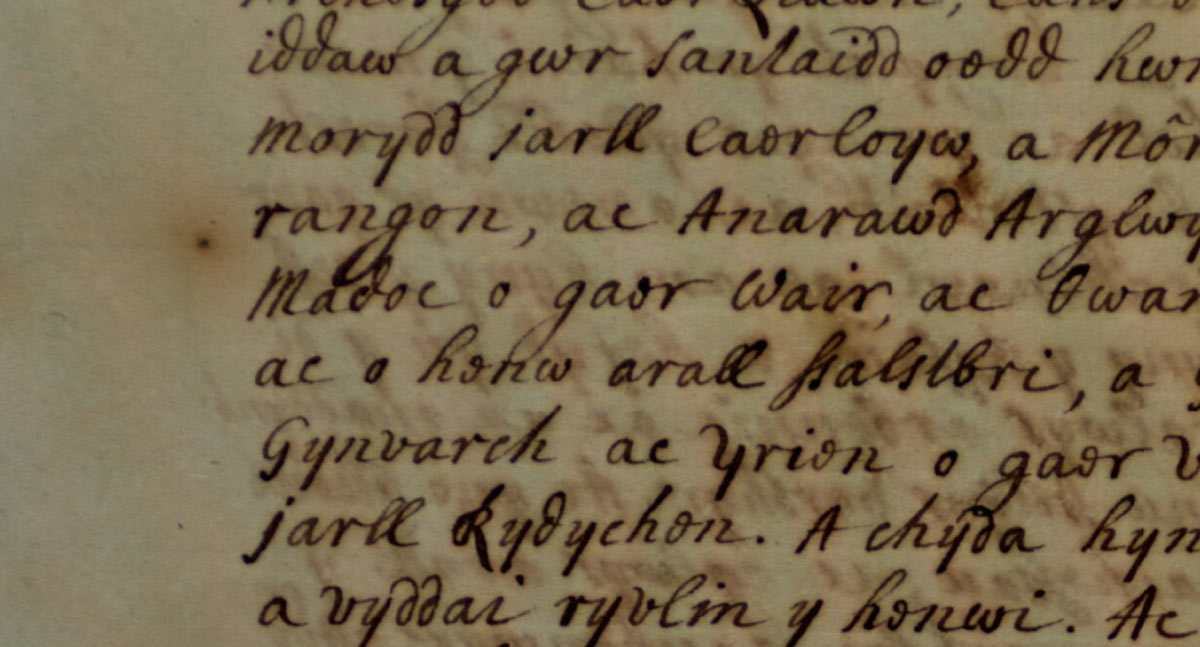

Another example of one of King Arthur’s brothers from Welsh tradition is seen in Culhwch and Olwen, which is the earliest Welsh prose Arthurian tale. This dates from c. 1100. It tells the story of Arthur engaging in a series of dramatic and difficult adventures to aid his cousin, Culhwch, in his efforts to win the hand of Olwen. At one point, Culhwch refers to Arthur’s many allies. What follows is an incredibly long list of names. One of them is as follows:

“Gormant the son of Ricca (Arthur’s brother by his mother’s side; the Penhynev of Cerniw was his father).”

According to this, Arthur had a half-brother. His mother, unnamed here, had evidently been married to the “Penhynev” (Chief Elder) of Cerniw prior to being married to Arthur’s father, Uthyr. Interestingly, this provides strong independent support for the story recorded by Geoffrey of Monmouth about Uther taking Igerna, the wife of Gorlois, Duke of Cornwall. Notably, “Cerniw” is a Welsh place name that can mean Cornwall.

According to many modern commentators, this text names Arthur’s half-brother as Gormant. This would mean that Ricca was the Penhynev of Cerniw, the former husband of Arthur’s mother. However, this would lead to a conflict with other aspects of Arthurian tradition. In Geoffrey’s account, he names the first husband of Arthur’s mother, Igerna, as Gorlois. In Welsh translations of Geoffrey’s work, the Welsh scribes often changed the names used by Geoffrey for names that were more familiar to their native traditions. Yet, in the case of Gorlois, they did not exchange it for the name “Ricca.” Rather, they simply wrote it as “Gwrleis” or “Gwrlais.” This suggests that they did not recognize Geoffrey’s Gorlois as equivalent to the Ricca from Welsh tradition.

An alternative possibility is that the parenthetical statement about Arthur’s half-brother is not actually a reference to Gormant. Since it comes immediately after the patronymic, it could instead be a reference to Gormant’s father, Ricca. In other words, it was Ricca who was the half-brother of Arthur and the son of the Penhynev of Cerniw, whose name is simply not included in the text.

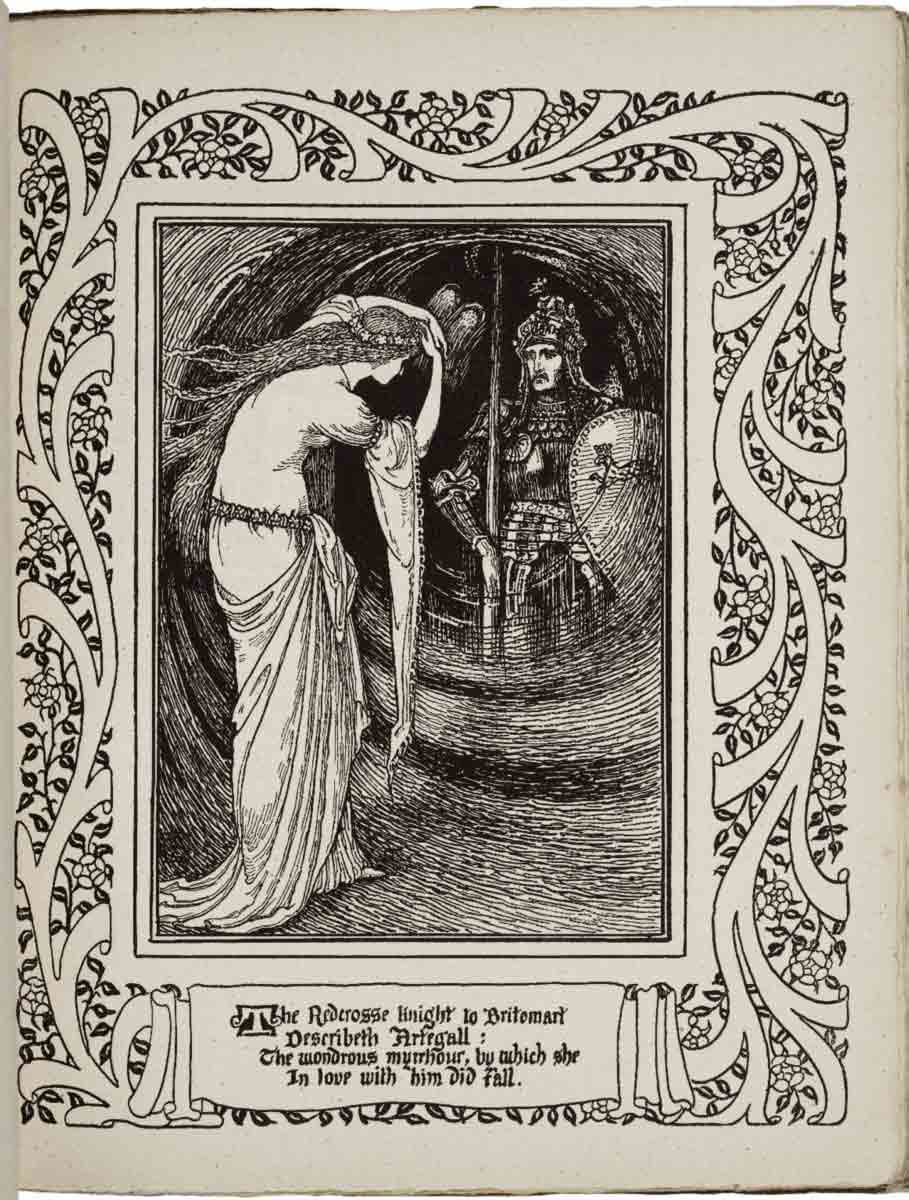

Artegall: Arthur’s Brother in The Faerie Queene

Another figure who appears as the brother of King Arthur in the Arthurian legends is Artegall. He is a character in Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, written in 1590. He appears as Arthur’s half-brother, the son of Gorlois rather than Uthyr. He is a champion of justice and engages in adventures, being saved at one point by his lover, Britomart.

Of course, Edmund Spenser’s text comes from long after the medieval Arthurian texts. Normally, Thomas Malory’s 15th-century Le Morte d’Arthur is viewed as the latest text that can be classed as part of medieval Arthurian tradition. However, this does not mean that Spenser made up the character of Artegall. In fact, there is clear evidence that he did not. There is general agreement that this character is merely Spenser’s adapted version of a character who appears in several Arthurian sources prior to Spenser, going all the way back to Geoffrey of Monmouth. There is also evidence that Spenser did not invent the idea that he was a brother of Arthur.

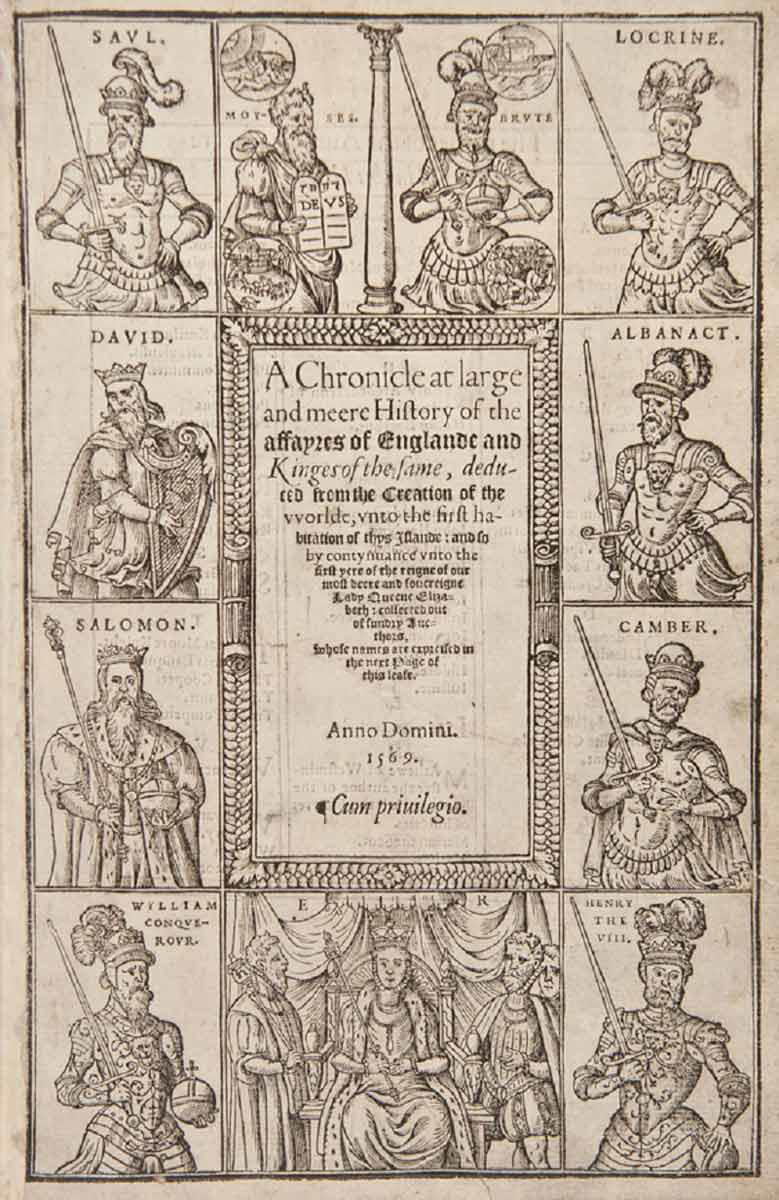

One source close to Spenser’s own time is Richard Grafton’s A Chronicle at Large, written about 30 years before The Faerie Queene. In this source, Grafton provided a brief overview of King Arthur’s reign. Immediately after this, he discussed the figure of Arthgal, an important person from Arthur’s time. While not providing very much information about him, he says that he was the first Earl of Warwick.

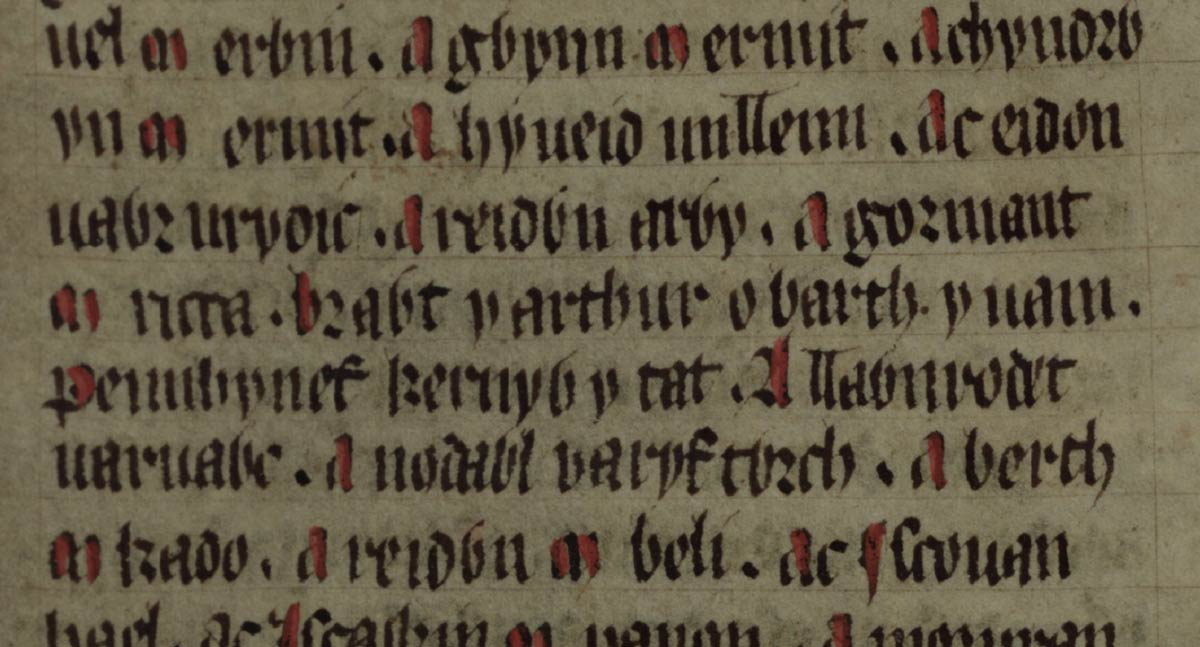

This character of Arthgal, Earl of Warwick, appears in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, written in c. 1137. He appears as one of Arthur’s many allies who attend his special coronation. While Geoffrey does not call Arthgal the brother of Arthur, there is evidence for this connection.

As mentioned earlier, the Welsh translations of Geoffrey’s work often exchanged names with different ones to better align with native Welsh tradition. Fascinatingly, in the Welsh Brut Tysilio, the name “Arthgal” is replaced with “Madoc.” The only Madoc associated with King Arthur in Welsh tradition is his brother. This suggests that the Welsh understood Geoffrey’s Arthgal (and, by extension, Spenser’s Artegall) to be Madoc, the brother of Arthur.

Were Any of These Brothers Historical?

So far, we have seen that Arthurian tradition provides Arthur with more than one brother. However, were any of them historical? After all, other family members of Arthur in the legends are known to have really existed. For example, the famous Saint David of Wales, who definitely existed, was said to have been Arthur’s uncle. Therefore, each family member needs to be assessed on their own merit.

In the case of Madoc, the fact that he appears so early in Welsh tradition supports the conclusion that he may have really existed. Interestingly, a figure with this same name, spelled “Matuc,” appears in the medieval Book of Llandaff as a witness to a land grant. The grant in question was overseen by King Meurig of Gwent, son of Tewdrig. While many scholars date Meurig to the 7th century, many others date him to the 6th century. If this latter suggestion is correct, then this would place this apparently historical “Matuc” in exactly the right time period to be Madoc. It would also place him in the right location since early Arthurian tradition closely associated him with the region of Gwent.

The Legendary Brothers of King Arthur

In conclusion, what do we know about the legendary brothers of King Arthur? Arthurian tradition assigns him at least two brothers. The earliest is Madoc, seen in a poem dating to potentially as early as the 9th century. He is best remembered for his death, which appears to have been connected in some way with dramatic natural events. Another brother was a half-brother who was either Gormant or his father Ricca. In view of Welsh tradition not replacing Geoffrey of Monmouth’s “Gorlois” with “Ricca,” it is likely that Ricca, and not Gormant, was Arthur’s half-brother.

A much later legendary brother was Artegall, from Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. Although this is a very late Arthurian text, there is clear evidence that the character of Artegall already existed in the Arthurian legends and had done so since at least c. 1137. He was Geoffrey’s Arthgal, Earl of Warwick. Welsh translations of Geoffrey’s work indicate that he was viewed as identical to Madoc.