From 1920 to 1946, the League of Nations was the main international organization designed to resolve international disputes. It proved to be inadequate for the coming of WWII. However, it also had successes that set a precedent for the UN. This article talks about several of these successes and what they proved in terms of multilateral diplomacy.

What Was the League of Nations?

The League of Nations was an organization intended to resolve international disputes and ensure peace around the world. Modeled on Westphalian principles of state sovereignty, it was an institution established by the Treaty of Versailles. It had multiple aims: to help refugees return after the end of WWI, stabilize the world economy and labor market, and resolve territorial disputes. It was the strongest multilateral organization to be created in history and it had enormous responsibilities.

Based in Geneva, the League was composed of three different bodies. First was the Assembly, where all members were represented. It met at least once a year and every member had a vote. Initially, the Assembly had representatives from 41 countries; membership would later grow to 63. Then there was the Council, which functioned like the UN Security Council. The Council had similar roles to the Assembly but also had special administrative tasks. It was composed of four permanent members and several temporary elected members. Lastly, the administrative body was the Secretariat. It headed the organization and supervised protocols in the meetings of the Assembly and Council.

Despite US President Woodrow Wilson’s instrumental role in creating the League during negotiations at Versailles, the League’s authority was undermined by the United States’ refusal to join the organization. Much of the world was under colonial rule and did not have an independent voice at League meetings. However, it also had accomplishments in the interwar period. It created the International Labor Organization and assisted with refugee resettlement. It also resolved several international disputes.

Yugoslavia vs Albania Dispute

When Albania gained independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1913, it sought to distinguish itself from its neighbors and offer a haven for Balkan Muslims. It faced serious challenges in the aftermath of WWI. The governing institutions of the country were weak, the economy was a mess, and neighbors on all sides had designs on its territory. It joined the League of Nations in 1920 and hoped to gain international acceptance.

Both Greece and the newly-formed Kingdom of Yugoslavia were alarmed by the creation of a Muslim-majority state in the Balkans. Both states sought to control Albanian territory and claimed that the country was oppressing Christians within its borders. Yugoslavia was especially paranoid about Albanian actions and, in 1921, proceeded to send soldiers into a disputed area on the border. They hoped to have support from the rest of the Christian world.

However, the League reacted quickly and in Albania’s favor. Representatives from Britain, France, Italy, and Japan arrived in Albania to take stock of the situation. The United States, while not a member of the League, was a major backer of the Albanian government, which had just moved its capital to Tirana. Upon receiving the commission’s report, the League held a vote that ruled in favor of Albania. Yugoslavia protested vociferously but had little support for its position and agreed to withdraw its troops. This action by the League averted a major war between the two states and demonstrated that smaller countries like Albania could effectively obtain diplomatic support from the League.

Åland Islands Dispute

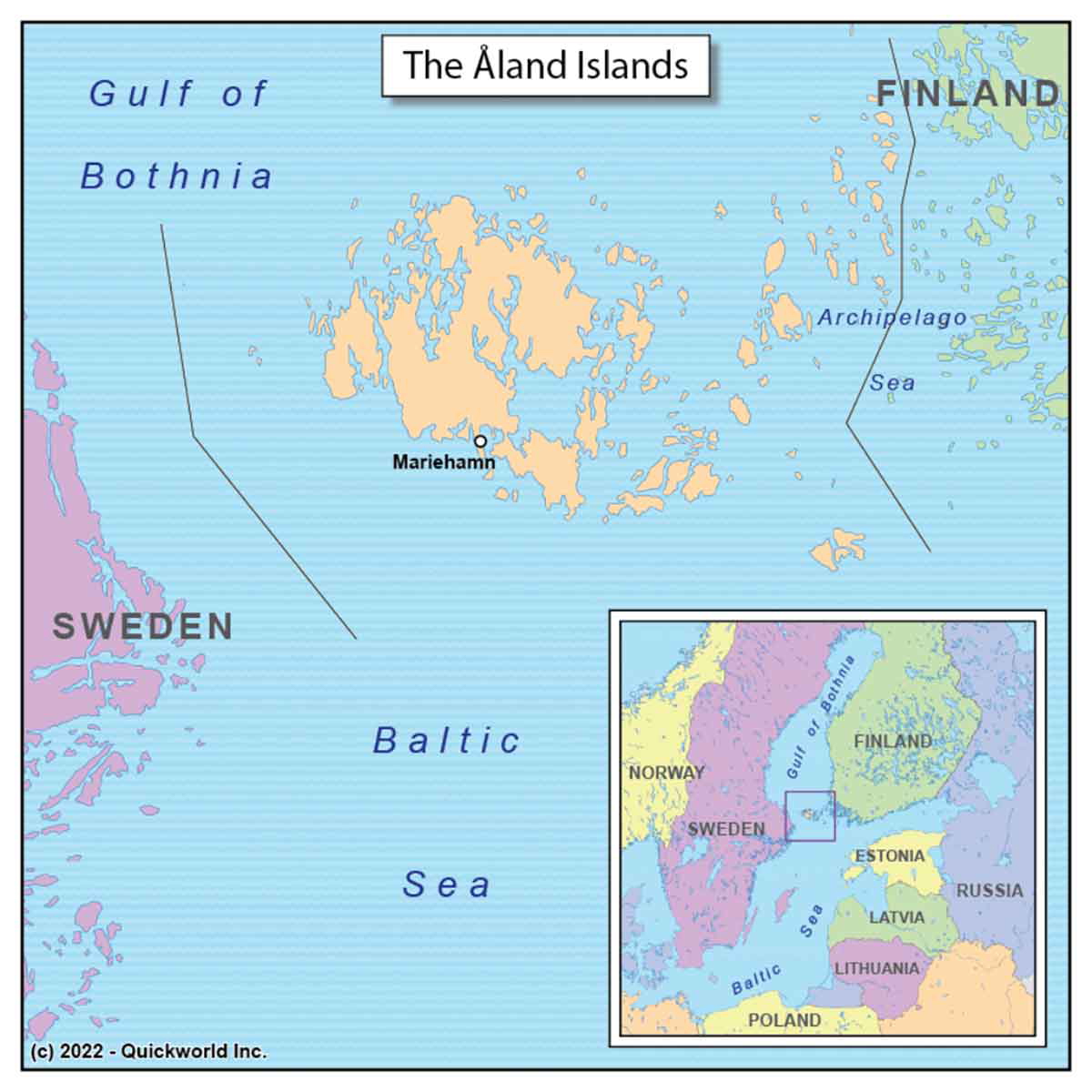

Further north, Sweden and Finland had their own dispute over the Åland Islands in the Baltic Sea. Strategically located in the northern Baltic, the archipelago had been under Swedish rule until 1809, when it was occupied and subsequently annexed by the Russian Empire during the Russo-Swedish War of 1809-1810. The islands were supposed to be demilitarized, but Russia built fortifications on them during the First World War. Most of its population were Swedish-speaking and Stockholm had long desired to reassert sovereignty over the islands.

Finland gained independence when the Russian Empire collapsed in 1917 but collapsed into civil war. The chaos and bloodshed from this war caused island residents to panic and demand Sweden take control. Once the war ended, Finland passed the Autonomy Act for the islands and promised full citizenship and rights for the residents. The Swedish government and local authorities rejected this approach and insisted that the islands belonged to them. Both countries went to the League to ask for guidance and plead their cases.

Initially, the League asked the International Committee of Jurists to rule if the League was able to take up this case. Once it received consent, the League proceeded to rule on the issue. The Council created a Commission of Rapporteurs to recommend a ruling. After they investigated, the Council passed a resolution stating that the islands were Finnish, but they must remain demilitarized, Swedish culture must be protected, and the islands must retain autonomy. Even though Stockholm was disappointed, they acknowledged the ruling and Finland asserted sovereignty over the islands.

Upper Silesia Plebiscite

The region of Silesia had been traditionally Polish but became part of Prussia following the Third Partition of Poland in 1795. Following the unification of Germany in 1871, Silesia became part of the new German Empire. The German authorities in Berlin sought to integrate the region into the area by settling the territory with ethnic Germans. This enraged the Polish majority, who feared that they would be overwhelmed by the newcomers. When Poland gained independence at the end of WWI, they sought to take control of the region from a weakened Germany.

The Silesian uprisings by ethnic Poles against Weimar Germany became very serious as a result of backing from the government in Warsaw. A large Polish community lived in Upper Silesia east of the Oder River, while Germans were in the majority to the west. As the uprising continued, the League of Nations sought to resolve the conflict by diplomatic means.

On March 20, 1921, the Upper Silesia region held a plebiscite to determine the fate of the region. Despite the presence of Entente soldiers to ensure order, the vote suffered from periodic bouts of violence. When the final vote was tallied, the result was inconclusive. Therefore, the League decided to partition the territory between Germany and Poland. Anyone who wanted to move to live with their ethnic kin was free to do so. Both Germany and Poland accepted the new border and it remained as such until 1939.

Creation and Administration of Danzig

One of the flashpoints during the interwar period was the city of Danzig/Gdansk. Under the Treaty of Versailles, the port city was designated the Free City of Danzig and administered by the League of Nations. This was to ensure that Poland had access to the sea while acknowledging the ethnic German majority in the city.

The League allowed Poland to control the Free City’s foreign relations. Poland also oversaw the waters off the city and the port facilities. However, the actual administration of the Free City fell under the League’s Council to ensure that the city remained neutral. The city’s budget fell under a local council elected in League-supervised votes. This arrangement worked for many years because the locals wanted peace. Additionally, neither Germany nor Poland initially wanted to fight over control of the city.

While the Free City remained calm for much of the interwar period, the rise of the Nazis changed how Germany viewed the city. Local elections saw the Nazi party gain with ethnic German voters. After 1933, the Germans decided to seize control of the local municipality and annexed the city in 1939. While the administration ended in failure, the League’s oversight of the city was seen as a success. The Council ensured that social services were provided and that the locals could vote fairly. The main challenge came from League members failing to uphold the mandate over the city.

Ending the Greco-Bulgarian Border Incident

Similar to the crisis between Albania and Yugoslavia, the League found itself trying to stop a war between Greece and Bulgaria in the Balkans. For much of the 19th and 20th centuries, Bulgaria and Greece sought control over disputed territories such as the area around the town of Petrich. Greece believed that the territory belonged to them because of the presence of ethnic Greeks. However, Bulgaria had sovereignty over the territory.

On October 22, 1925, a Greek soldier on the border chased after his dog when it ran into Bulgarian territory. Bulgarian guards panicked and fired, killing the Greek soldier in the process. Bulgaria hoped to defuse the situation and apologized for the incident. In retaliation, Greek troops reportedly crossed the border into Bulgaria and took control of Petrich, while both sides sent reinforcements to the disputed area.

Amid concerns that a general war could break out between Greece and Bulgaria, the League reacted quickly to bring an end to the dispute, sometimes known as the War of the Stray Dog. Although Greece stated that its incursion was not meant to be a land grab, the League immediately ordered Greek troops to withdraw. It also ordered Greece to pay an indemnity for attacking Bulgarian soil. While the deal was considered excessively harsh towards Greece, it prevented another Balkan conflict from breaking out and reiterated the importance of territorial integrity. League members were concerned about Greek expansionism and hoped that they could urge Athens to stop demanding control over neighboring territories.

Laying the Foundations for the United Nations

The League’s ignominious end meant that the organization was considered a systemic failure of international diplomacy. The failures to stop Germany, Japan, and Italy from building their empires and starting WWII demonstrated the internal weaknesses of the League. Additionally, the lack of representation of colonized nations meant that the League was dominated by Europeans. Its failure to resolve disputes over territories like Corfu and the Ruhr reflected the institutional malaise.

However, the organization’s successes offered a blueprint for the United Nations. Its ability to mediate in certain disputes in the Baltics and Balkans demonstrated effective forms of multilateral diplomacy. The assistance it provided to refugees foreshadowed the work of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The League’s creation of the International Labor Organization marked the first time international labor standards were set up by an international organization. Lastly, the League’s structure proved to be very similar to the United Nations with the Assembly, Council, and Secretariat. For all its ignominy, the League of Nations still lives today in the United Nations, just with larger membership and a stronger mandate.