The consequences of settler colonialism linger long after the colonizing power has left and the former colony has gained independence, leading to persistent inequalities and scarring societies to the core. The most visible of these scars is the death toll caused by anti-colonial uprisings and their repression. In 1947, Madagascar was the scene of a brief but violent uprising against French rule. France responded with a brutal crackdown that crushed resistance and left thousands of people dead. In Chile, the actions of the Mapuche organization Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco (CAM) remind us of the continuing effects of colonialism and capitalism on the land.

From Settler Colonialism to Independence

In some cases, it is easy to pinpoint the exact moment when a previously independent country comes under the control of another power, the moment when it becomes, in other words, a colony. Similarly, the moment when a former colony regains its independence—whether through armed struggle, legal means, or non-violent efforts—is often commemorated annually with public celebrations and collective re-enactments aimed at fostering a sense of community and shared history.

However, determining when the political, social, and cultural influence of the former colonizing power over the newly independent country ends, if it ever does, is a far more complex issue. Settler colonialism doesn’t end when the occupying army leaves the country. Its legacy is complex, far-reaching, and, above all, long-lasting. The first and most visible consequence of anti-colonial uprisings is the (often estimated) number of deaths.

In Kenya, for example, between 20,000 and 100,000 people, mostly Mau Mau fighters and civilians, died as a result of the eight-year-long struggle against British rule, now known as the Mau Mau Uprising, between 1952 and 1960. Initially, 11,503 Mau Mau fighters were reported killed. In Algeria, the estimated death toll was much higher. Over eight years, between 300,000 and 1,500,000 Algerians and French settlers died as a result of France’s determination not to give up on its colony in North Africa during the so-called Algerian War of Independence. Other estimates range from 45,000 to 1.5 million.

The Angolan War of Independence—also known as the Armed Struggle of National Liberation—was fought between 1961 and 1975 to shake off Portuguese rule and left between 50,000 and 100,000 people—Angolan civilians, “rebels,” and Portuguese soldiers—dead.

Intergenerational trauma, it has been shown, is passed down through generations and continues to disrupt society long after the conflict is over and/or independence is achieved.

The concept of intergenerational trauma first emerged in the aftermath of the Holocaust and was used to describe the mental health issues and behavioral problems of the children of Holocaust survivors. Over the years, studies have proliferated describing a wide range of difficulties including, but not limited to, “feelings of over-identification and fused identity with parents, impaired self-esteem stemming from minimization of offspring’s own life experiences in comparison to the parental trauma, tendency towards catastrophizing, worry that parental traumas would be repeated, and behavioral disturbances such as experiencing anxiety, traumatic nightmares, dysphoria, guilt, hypervigilance and difficulties in interpersonal functioning” (Yehuda & Lehrner).

Such trauma effects have subsequently been observed in other countries, among the children and grandchildren of war survivors, from Vietnam to Northern Ireland.

Achieving Independence

Decolonization through violence often leaves a legacy of political instability. Economies are fragile, bent by years of exploitation and unrest. A war-torn economy often takes years to recover. In the meantime, the country’s citizens are the ones called to pay the highest price. Vietnam, for example, emerged victorious from its “Resistance War Against America”—the Vietnam War, as it is commonly known in the Western world. Throughout the 1980s, until the Doi Moi Reforms began to bear fruit, it remained one of the poorest countries in Asia, its war-torn economy unable to sustain its traumatized and bitterly divided citizens.

Some three million refugees from Vietnam and neighboring Laos and Cambodia fled their homes, some crossing the border into Thailand and China, others by boat trying to reach Indonesia, Singapore, Hong Kong, the Philippines, and Malaysia. Australia, Canada, the United States, and France also received thousands of South Asian refugees.

The legacy of settler colonialism not only weakens a country’s economy but also its social fabric, causing and/or exacerbating tensions between different groups. In Madagascar, for example, ethnic tensions between the Merina (or Hova) and various coastal groups, particularly in the Toamasina region, dramatically resurfaced a decade after the country gained independence from France in 1960.

Immediately after gaining independence from Portugal after 14 years of struggle, Angola was rocked by a bloody civil war that lasted for 26 long years and caused the deaths of between 500,000 and 800,000 people—although some estimates put the death toll at around one million. Four million people were displaced. The very fabric of Angolan society was shattered after 40 years of armed struggle and civil unrest.

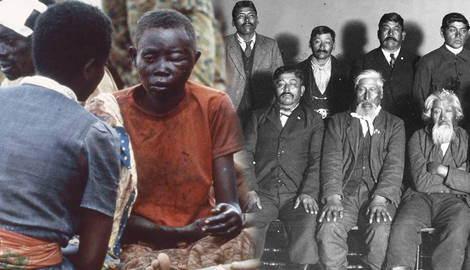

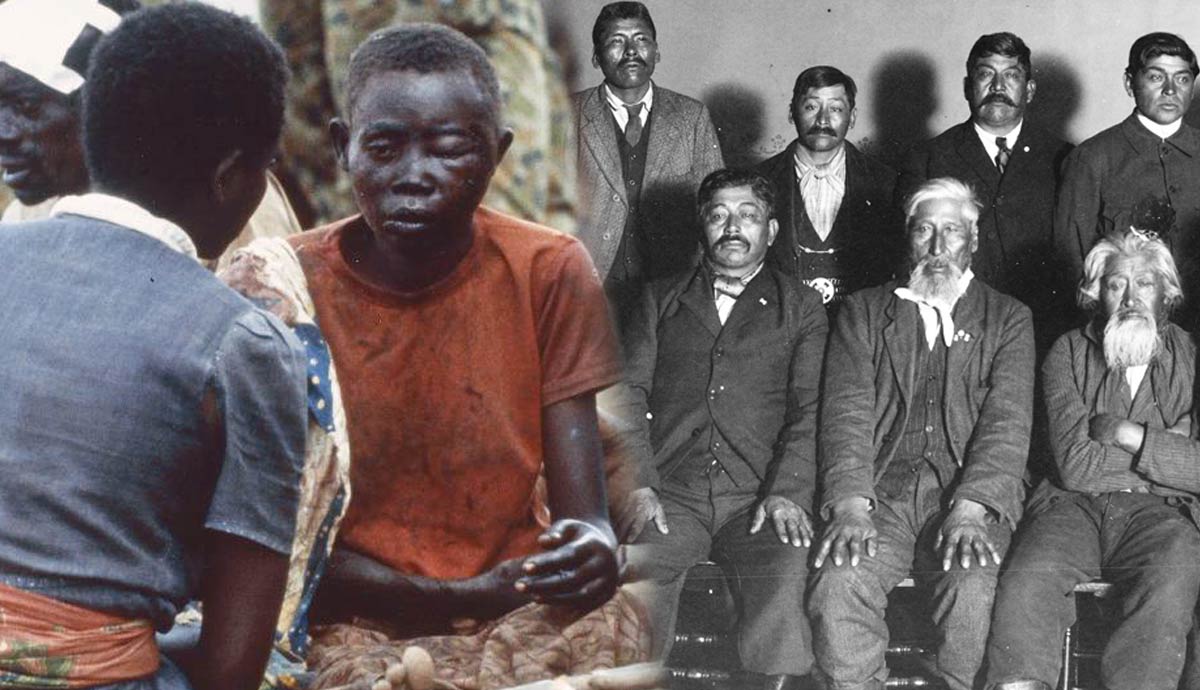

When Madagascar Rose Against the French in 1947

The Malagasy Rebellion, the founding event of Madagascar’s national history, was short but bloody. To understand its causes, its victims, and its consequences for Madagascar’s society, it is necessary to start with the two main nationalist parties active at the time, the MDRM and PADESM. MDRM stands for “Democratic Movement for the Malagasy Renovation” and was the first Malagasy political party to send its members to the French National Assembly. While the party openly advocated for the independence of Madagascar from France, its founders—who belonged to the Merina élite—envisioned Madagascar’s independence as the first step in regaining the political and social control of the island that the Merina had enjoyed for centuries before the arrival of the French.

PADESM, literally “Parti des déshérités de Madagascar” (“Party of the Disinherited of Madagascar”), was formed largely in opposition to the MDRM by people from the country’s coastal communities whose ancestors had been subjugated, exploited, and enslaved by the Merina.

This is the case, for example, for the groups living in the Toamasina region, north of Antananarivo, on Madagascar’s east coast, whose local groups were conquered by Merina leaders in the 19th century. As Jennifer Cole points out in her Narratives and Moral Projects: Generational Memories of the Malagasy 1947 Rebellion, “With colonization, these divisions and alliances were reworked in new ways as colonial rule both fostered a sense of pan-Malagasy subjugation vis-à-vis the French and recast tensions between Merina and coastal peoples in increasingly ethnic terms.” Thus, long before French rule and the 1947 rebellion, Malagasy society was bitterly divided.

This division continues in the way the uprising is remembered, an issue that Cole researched and reported on extensively after interviewing dozens of Malagasy in both rural and urban areas in the 1990s. In 1946, when the MDRM and PADESM were founded, there were around 35,000 French people living in Madagascar.

The uprising began in the eastern part of Madagascar. On the evening of March 29, Malagasy armed with spears attacked and burned down several administrative centers of French power on the east coast. The Tristani police camp at Moramanga was attacked and looted. French colonial administrators were killed along with French settlers. French-owned plantations in Manakara and along the Faraony River, which flows south from the central highlands to the Indian Ocean, were also attacked and looted. News of the uprising spread like wildfire to the south, to the Lake Alaotra region, the island’s northern central plateau, the central highlands region, and the capital, Antananarivo. By this time, the number of Madagascan rebels, supported by thousands of peasants, had reached 2,000. For the first few months, the French response was timid. But then, after tripling the number of troops on the ground, the French response was brutal.

The French authorities at the time believed that the uprising was a “Merina plot,” organized by the leaders of the MDRM, who had until then sought independence through peaceful and legal means, mainly negotiations. The French authorities also suspected that the rebels were being stirred up and secretly subsidized by the United Kingdom and the United States.

As would happen a few years later in Algeria, another French colony, the French government responded with violent repression through forms of individual and collective punishment. French soldiers burned down towns they believed supported the uprising, slaughtered peasants’ cattle, and executed thousands of “rebels.” Between 90,000 and 100,000 Madagascans died during or as a result of the rebellion, mostly in the Toamasina province, one of the most populous and culturally mixed regions of Madagascar. However, as is often the case, the number of victims remains controversial.

Many were tortured and executed by the French, while others died of starvation. In addition, around 1,900 Madagascans were killed fighting for France. According to historian Jacques Tronchon, by the end of the uprising in December 1948, some 550 French had been killed. More than half were soldiers. In the aftermath of the uprising, French authorities played a careful game of finger-pointing. In addition to dissolving the MDRM and temporarily suspending PADESM, they openly framed the uprising as a Merina plot, pitting one Madagascan group against another, and even supported and encouraged the establishment of public tribunals.

The Mapuche’s Struggle for Self-Determination Continues

The actions of the Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco (CAM), an armed Mapuche organization operating in Chile, are rooted in a complex history of dispossession and attempted cultural erosion first by Spanish colonizers and then, after 1810, by the Chilean government.

The Mapuche, the Indigenous people of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina, were violently dispossessed by the Chilean state during the so-called “Pacification of Araucania,” between 1861 and 1883, when their lands were seized, subdivided, and handed over to settlers. The dispossession of Mapuche lands continued well into the 20th century, particularly during the bloody right-wing military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1915-2006), between 1973 and 1990.

The actions of CAM today, and those of other Mapuche activists not necessarily associated with CAM, are directly linked to the resistance their ancestors waged first against the Spanish during the violent, prolonged Arauco War (or Araucanian Wars) in the 16th century, and then against the Chilean government.

In fact, until the Pacification of Araucania, the Mapuche managed to maintain greater political independence than other Indigenous groups, with the Biobío River, the second largest river in Chile, representing “la Frontera,” the border marking an area under Mapuche control that was not incorporated into the Chilean state. The Spanish called the Mapuche Araucanians, a name that many Mapuche today reject as a symbol of Spanish colonization.

CAM’s approach and motivations are both anti-colonial and anti-capitalist. Founded in Tranaquepe in 1998, CAM seeks to reclaim and regain control of ancestral Mapuche lands, to farm them using traditional methods and to protect them from mining and logging companies. They call their land occupations “recuperaciones territoriales.”

Since the 1990s, CAM has resorted to arson attacks and sabotage against logging trucks, machinery, and the property of landowners and corporations in the Biobío region, particularly in Tirúa, Cañete, and Contulmo, in the province of Arauco, and in Temucuicui.

Their ultimate goal is the restoration of part of Wallmapu, the historical territory inhabited by their ancestors. In the Mapuche language, also known as Mapudungun (literally, “the speech of the land”), Wallmapu translates as “a set of surrounding lands” and/or “Universe,” with mapu meaning “land” (or “territory”) and wall meaning “surrounding” or “encompassing.”

The actions of the Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco in Chile and those of their Mapuche ancestors at the time of Spanish colonization, as well as the 1947 Madagascar uprising against the French, are a powerful reminder of the legacy of settler colonialism—a legacy of violence, cultural aggression, dispossession, land usurpation, anti-colonial uprisings, and repression, a legacy that has left thousands of dead, both civilians and soldiers and thousands more emotionally scarred.