Today maps are considered primarily a tool for navigation, but medieval maps were so much more. They reflected how Europeans understood the world before the Age of Exploration. Blending myth, religion, and limited geography, they showed how medieval explorations took place, as well as combining elements of reality and fantasy.

Why Medieval Maps Were Made

World-views during the Middle Ages were markedly different from today. The prevailing maps of Europe in that time period were less about plotting course and getting somewhere, and more about representing the cosmos and Christendom. Some maps of the Holy Land were used both as a visual representation, and to give a path or instructions on how to take a pilgrimages. These maps were also used as a way of teaching and expressing ideology rather than simple navigation.

How Religion and Myth Shaped Medieval Cartography

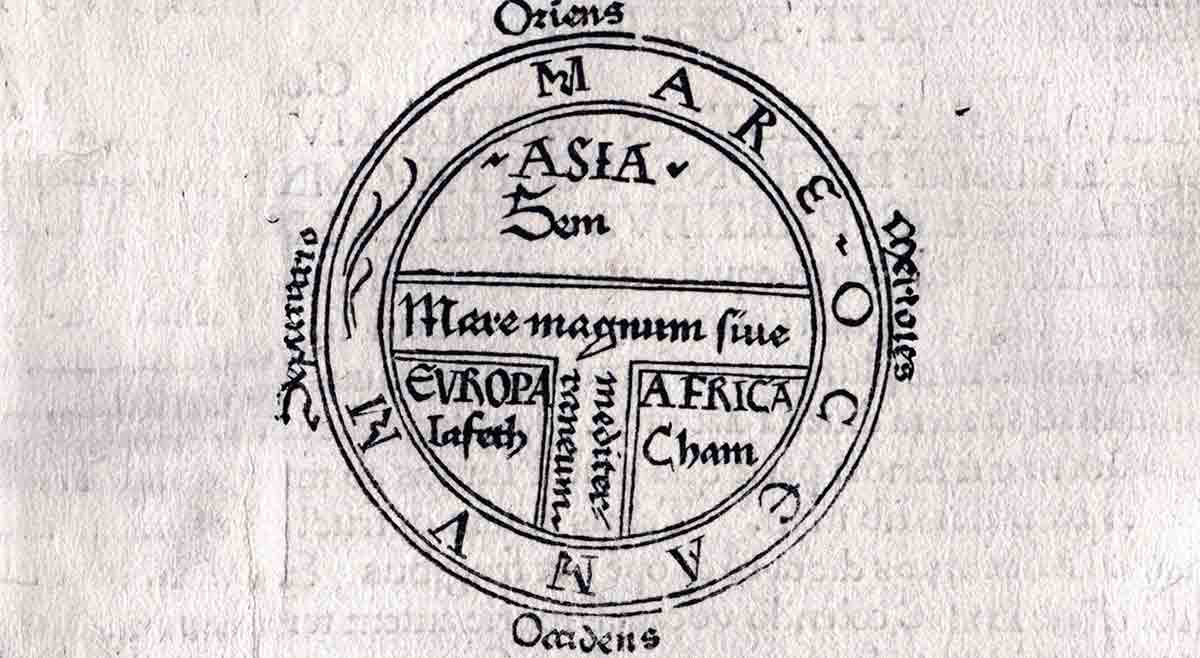

Examples of maps where religion is the centerpiece include the “T and O” maps. They show a symbolic representation of God’s created order, and Christendom’s place within, it while expressing the ocean and known lands in vague sections rather than defined land masses. The “T” is a symbol of the cross, and Jerusalem is the center and most important part of the world.

One other key difference in how maps were made then compared to now is orientation. Our convention of “north is at the top” was not universally adapted. Instead, different places used a different focal point at the “top” of the map, and those that used the same one could differ in orientation based on where they were located.

Latin Christian maps placed east at the top, because east was pointed towards the rising sun. Other religions would point towards the city of Jerusalem as the “top” of the map. Even other countries outside of Europe used different orientation.

In China, the Tang and Song dynasties saw advancement in map making. Cartographers like Jia Dan used grid-based maps that we are now familiar with scales to include rivers and boundaries. The top areas of Chinese maps were most often South, due to facing the emperor’s southern throne. The throne would be placed at the top, rather than religious orientations. Another key part of religious imagery on maps, such as on the Ebstorf Map, was to include Christ’s head at the top, with the hands on either side.

Geographic Knowledge Among Medieval Europeans

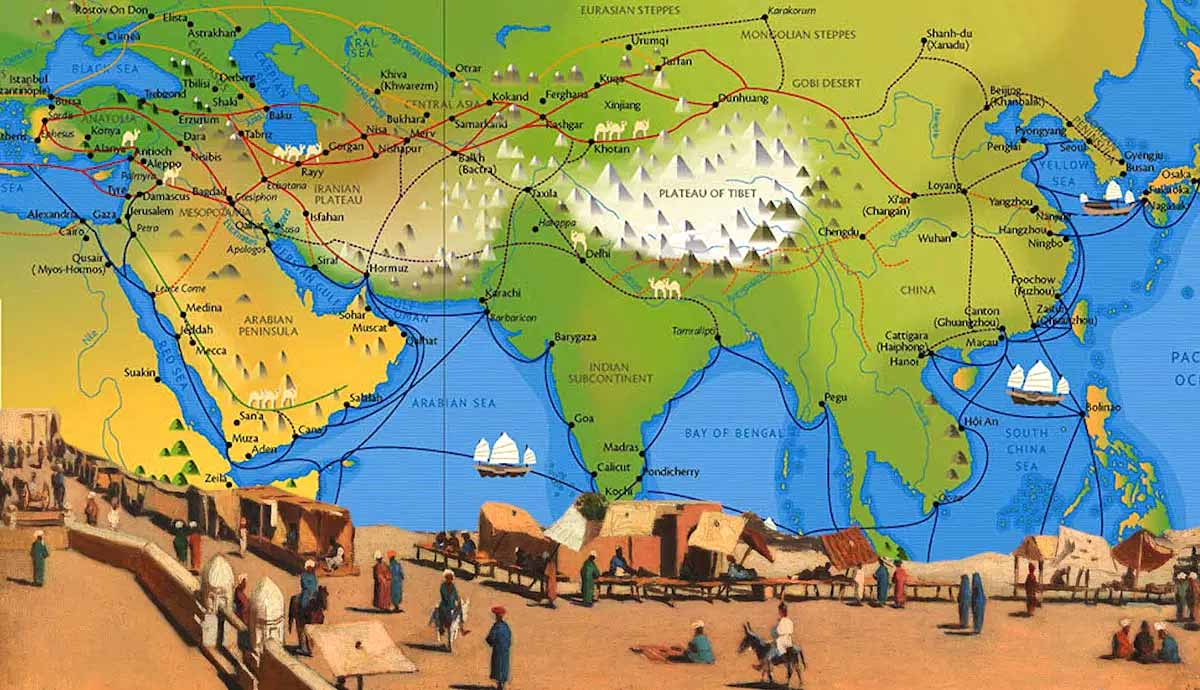

Geography wasn’t unknown during the Middle Ages, especially amongst scholars and higher ranks who had tutors, although it was far more limited than today. Few people who traveled were able to go far enough to see distant lands. Most of the knowledge of places were second-hand reports of travel narratives, books, and merchants who traveled during trade. They understood, for example, the vast size of Asia, but they did not understand the specific area, coastline, or geography.

So, while Europeans in the Middle Ages understood the overall frame of geography, and some far off countries, larger seas and oceans, and trade routes to countries, like the Silk Road, the details were more vague. Maps that were studied blended fact with tradition and theology; enough to give a general worldview, but not enough to actually travel with.

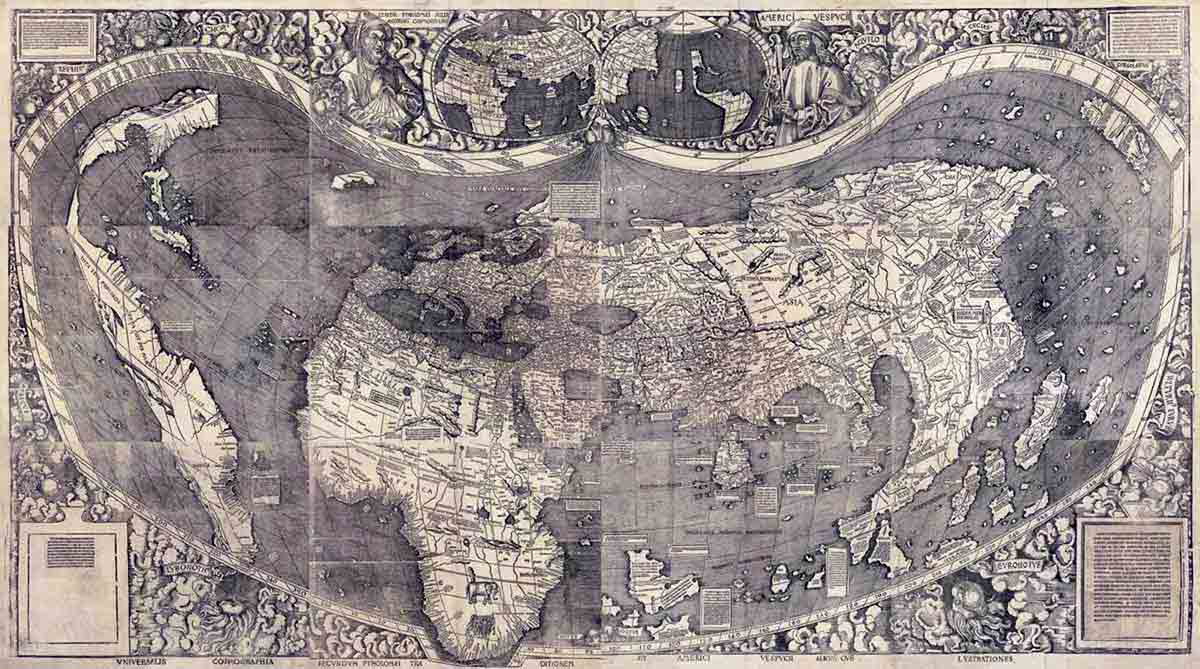

How Medieval Maps Influenced Early Explorers

Contemporary historian Richard Pflederer talks about the importance of being able to navigate the seas in order to be successful in trade and growth. While early maps weren’t always accurate, they gave an idea of what could be. The infusion of medieval spatial ideas with voyages meant explorers were mapping the expectations and adjusting later for actuality. These journeys to coastlines of other countries and interests in discovering new waterways used charts and maps that gave an impression of the world and land they were headed to.

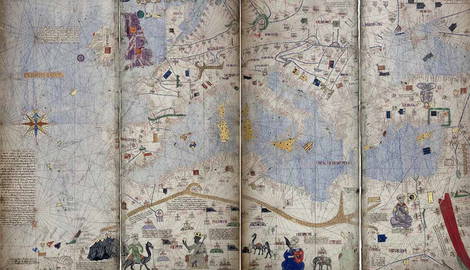

It was a unique mix of fact and fiction that eventually grew into a backbone of European exploration when combined with tools sailors already used to navigate on the seas. This included the portolan chart; a nautical chart developed in the Mediterranean.

Myths Surrounding Medieval Maps

Many modern audiences today envisage medieval maps that are decorated, covered in dragons, sea serpents, and warnings of the world’s edge, and that the people in that time actually believed the world was flat and that dangerous creatures roamed the ocean ready to swallow boats. So, what was the truth, and what was on the maps?

Most mappae mundi did include highly decorated images on the edges, and sometimes icons that were seamlessly decorated into the map itself. However, the image generated from popular culture is a myth that comes from a romanticized notion of maps, rather than reality.

One of the most well-known myths of maps is about dragons. While many times strange being adorned the edges, they were not meant literally, but a representation of morality and spiritual boundaries. These creatures included blemmyae without heads and sciopods without feet. Dragons, however, don’t show up on maps that were created in the Middle Ages.

Another myth was the idea that people thought the world was flat. Most scholars believed that the world was a sphere. Since these were not used for actual travel, there was no need to create accurate proportions.

What Maps Reveal About the Medieval Mindset

About 1,100 maps survive today that are dated between the eighth and fifteenth centuries, during the Middle Ages. It is from these maps that we are able to understand the map makes and those who would study them.

We know the importance of religion based on how European countries oriented their maps, not by directional north, but by religious locations. While they did not use these maps for the entire purpose of travel, they still played an important role in their society. For the viewers of that era, the map allowed them to see their place in God’s story. To track the changes of these ancient charts, those that came before, and how they evolved through the Renaissance to modern maps show what societies held important to their culture.