Between 1512, when the Sistine ceiling was unveiled, and 1533, the year Pope Clement commissioned the artist to work on The Last Judgment, Michelangelo’s life was eventful and, at times, in peril. Michelangelo had returned to Florence to resume work for the Medicis. In the years that followed, galvanized by the Sack of Rome, the citizens of Florence ousted the ruling Medici family. Michelangelo found himself imprisoned, sentenced to death, and eventually reprieved. Following Pope Clement VII’s death, his successor Paul III, demanded that Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment be painted.

Before Michelangelo’s “The Last Judgment”: The Canvas is Prepared

Before Michelangelo even put paint to plaster, the vast surface of the altar wall had to be prepared to his exacting standard. He had already argued with his long-standing friend and fellow artist, Sebastiano del Piombo, that the work should be completed in fresco, not in oils as Piombo had suggested. The Pope was drawn into the debate but, terrified of aggravating Michelangelo, sided with him. Vasari tells us that the Pope felt such reverence and love for Michelangelo that he always went out of his way to please him.

With the medium settled upon, a further year of preparations began. Most notable among the changes made was the destruction of Pietro Perugino’s original Assumption of the Virgin, which had covered the wall before Michelangelo’s commission.

It is believed that two further works by Perugino, which flanked the Assumption, were removed too. Raphael’s famous tapestries were simple to remove. However, some of Michelangelo’s paintings for the chapel ceiling were destroyed to accommodate the artist’s vision for what Pope Paul expected would be a masterpiece. Measuring 48 x 44 feet, the design for the fresco required structural changes to the altar wall in addition to the removal of artworks to ensure that Michelangelo’s canvas was expansive enough for his monumental concept.

A Star-Studded Cast

Pope Clement’s choice of The Last Judgment for the fresco was supported by his successor, Pope Paul III. The effects of the Sack of Rome, which had devastated the city in 1527, were still being felt in 1534. The violent attack had long-lasting consequences for both religion and Rome’s identity as a Papal state. Pope Clement had seen The Last Judgment as a symbol of the continuing relevance and power of the Catholic Church in an ever-changing political and religious landscape.

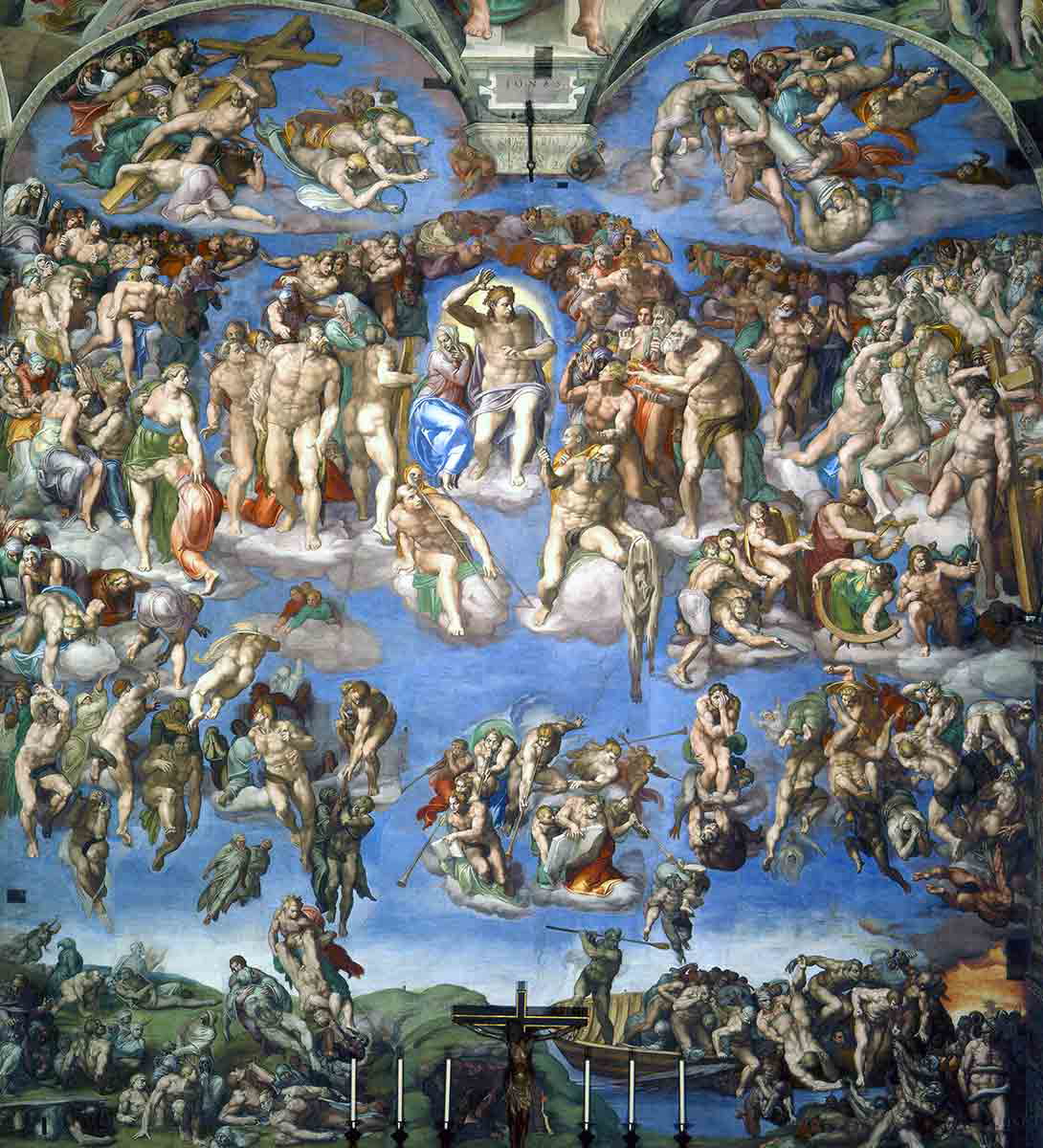

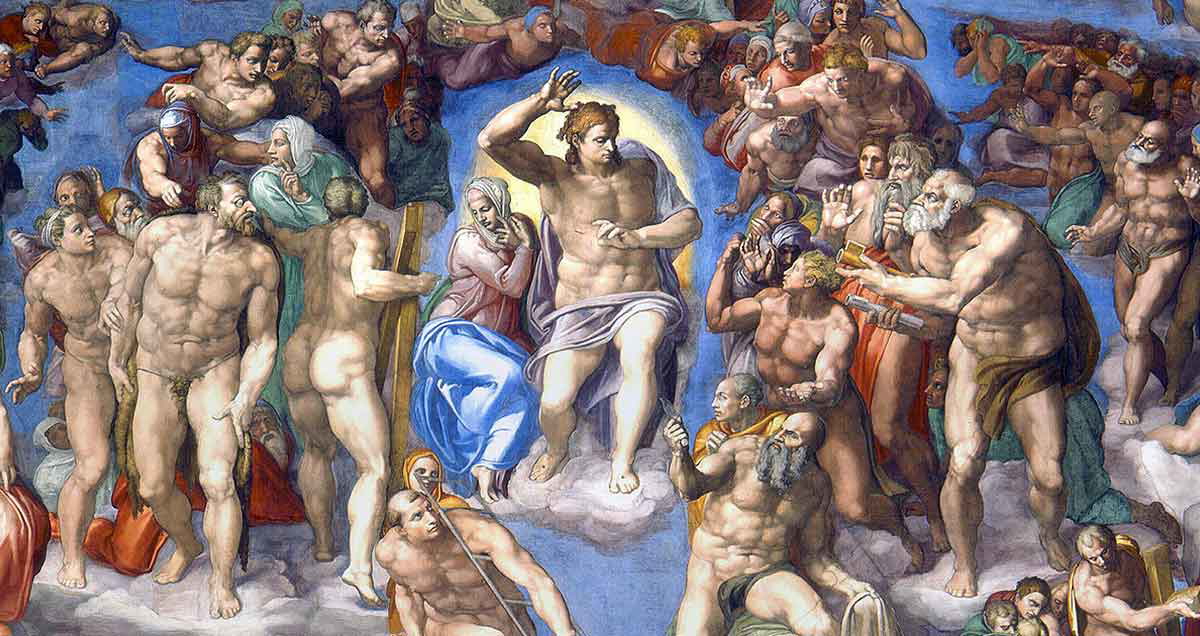

At the center of his composition, Michelangelo focused on Christ. Rising above the turmoil of bodies beneath him, he is portrayed as a beardless, muscular, and powerful man more akin to a Greek god than the customary bearded, gentle man depicted in Western art. The Virgin clings to his side, encompassed by the golden glow emitted by her son. They radiate light and warmth, although Christ’s hand is raised and ready to decree judgment on mankind: a threatening gesture intended to strike terror into the heart. His right hand, raised in a gesture known as ostentatio vulnerum or the display of the wounds, is a reference to the suffering of his crucifixion.

Vasari points out in his Lives that Michelangelo refused “to paint anything save the human body in its most beautifully proportioned and perfect form and its greatest variety of attitudes.” His composition of over 300 bodies, writhing and fearful, illustrates this. The work has no frame, perhaps suggesting the vastness of the enterprise that Christ is embarked upon. It has been suggested that the lack of frame is a device used to immerse the viewer in the scene and to remind them of their sins and the judgment that awaits them.

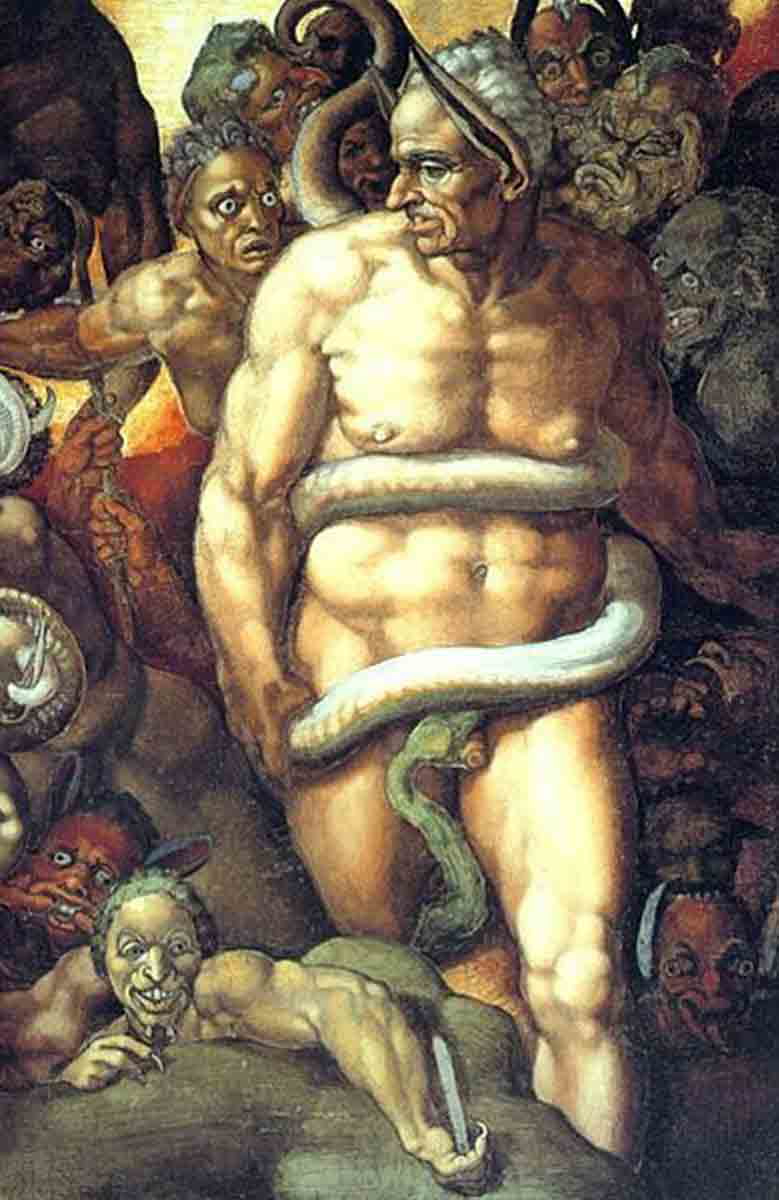

Surrounding Christ and the Virgin, Michelangelo includes a pantheon of saints, each bearing their attribute. We see Saint Peter with the keys to heaven and Saint Catherine with part of the wheel to which she was bound. Although the artist naturally included many of the primary characters of Christianity, he drew inspiration too from mythology. Charon, Greek mythology’s ferryman, is shown wielding his oar as he conveys the damned to hell. Close by, Minos, bestowed with the ears of an ass, his sinfulness illustrated by the snake that bites his genitals. He waits at the edge of hell, judging its entrants before deciding on their destiny.

Heavenly Bodies: Angels Not Demons

Although Michelangelo’s composition may, at first glance, seem chaotic, if we consider Christ as the pivot for the swirl of humanity that rises to his right and falls into eternal damnation to his left, the scheme becomes clearer. In the symbolic light of the upper reaches of the fresco, Michelangelo painted two lunettes, illuminating groups of angels carrying the attributes of Christ’s Passion. The artist had instructed that this part of the wall be constructed to protrude around a foot to ensure that those at the altar could see it if they looked up. It was intended that they remember Christ’s sacrifice and Resurrection, following which all people would be judged.

Angels appear, too, in the space beneath Christ, blowing trumpets to wake the dead from their graves. They hold the book of the damned, angled towards those heading for hell, guaranteeing that their sins are made known. To the right of Christ, they are depicted pulling the enshrouded dead upwards and into the orbit of their final judgment.

Michelangelo’s Self-Portrait?

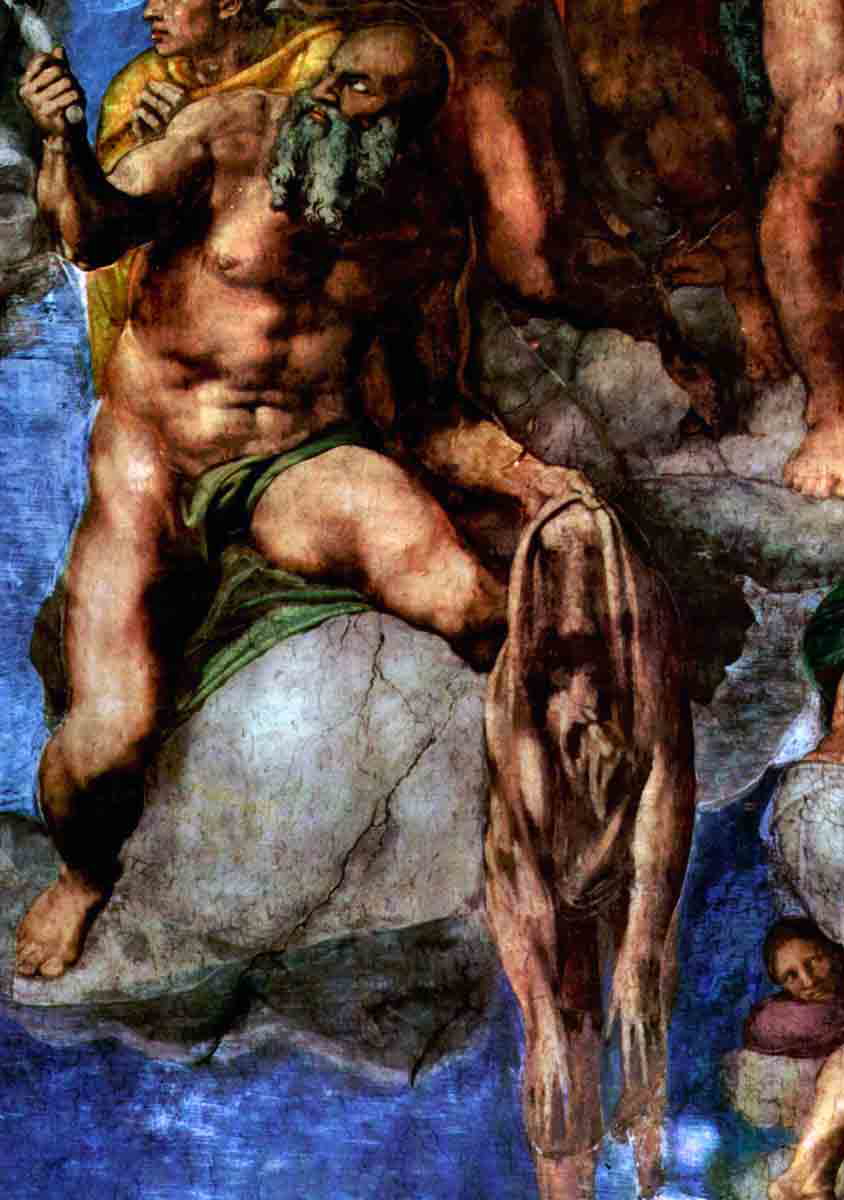

Below Christ and to the left, Michelangelo painted Saint Bartholomew holding the flayed skin of a man in his left hand. In two 4th century accounts, he is recorded as the apostle who introduced Christianity to Armenia but was flayed alive as a punishment for his conversion of the king to the religion. In artworks, he is often portrayed with his skin in his hands. In the case of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, though, it has long been believed that the flayed skin held by the saint is a self-portrait of the artist.

The Descent Into Hell: The Sinners Are Damned

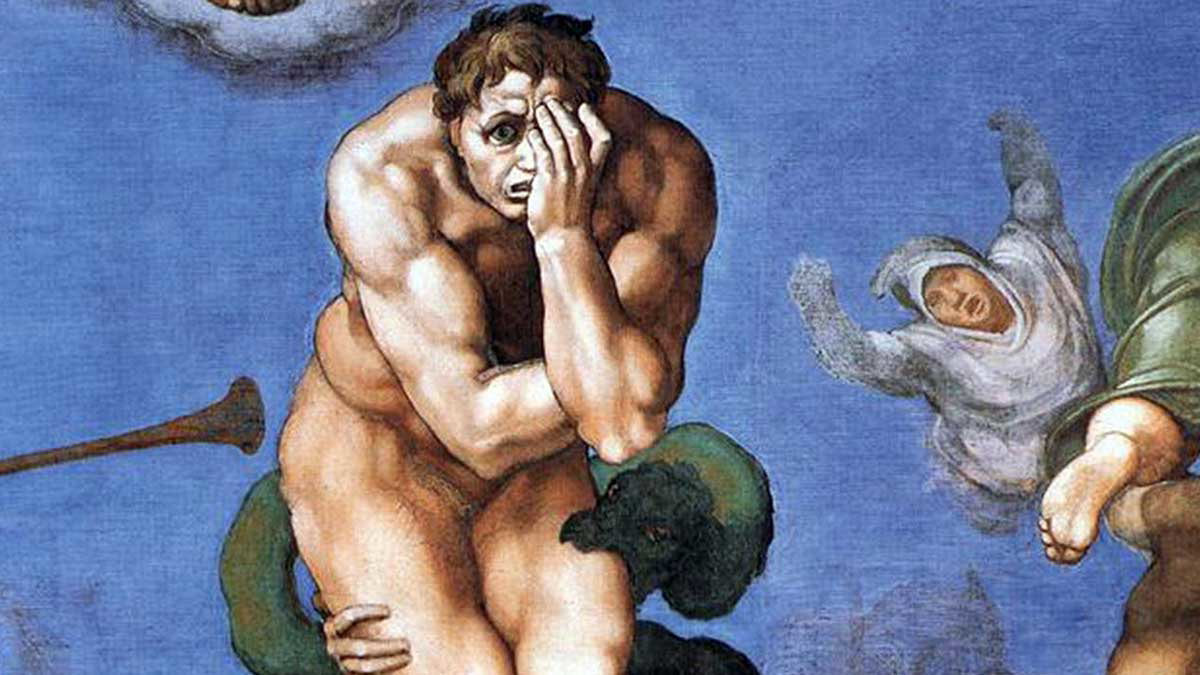

Completing the cycle of judgment depicted by Michelangelo, the lower right-hand corner of the fresco shows the descent into hell of the damned. Here, the viewer can see parallels between Michelangelo’s depiction of the Underworld and his inspiration, Dante’s Inferno. The devil himself is not shown, instead the artist creates an array of demons, engaged in pulling the damned down into the Underworld. Just below Saint Bartholomew and his flayed skin (Michelangelo’s self-portrait), we see a figure perched on a cloud, his despairing face in his hands. He has been damned and is being dragged toward hell by two ferocious devils. The proximity of the flayed Michelangelo self-portrait to the devils and the damned is perhaps a comment on the artist’s concerns for his judgment. He is suspended in limbo between Christ and the Devil.

In the central lower portion of the image, a dark and fiery cavern stretches deep beneath the ground. Demons peer from within. It is thought that, placed as it is between the souls being torn from their graves on the left of the composition and hell on the right, it represents Purgatory. As souls can escape from Purgatory, it makes sense that Michelangelo placed it close to where the priest would preach Mass in the chapel so the faithful could ponder their fate.

Controversy Erupts as “The Last Judgment” Is Unveiled

According to Vasari, Michelangelo had completed around three-quarters of the fresco on the altar when he was visited by Pope Paul and his master of ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena. Biagio vented his fury at the disgraceful depiction of nude bodies that covered the entire altar wall. Vasari tells us that Biagio claimed that “it was no work for a papal chapel but rather for the public baths and taverns.” Michelangelo was understandably furious at Biagio’s comments. The image of Minos, mentioned earlier, was Michelangelo’s revenge. Shown with a serpent wrapped around his legs and biting his genitals, he was said by Vasari to have the face of Biagio.

On Christmas Day in 1541, the doors of the Sistine Chapel were opened, and The Last Judgment was on view to the people of Rome. It was widely accepted as a masterpiece with Michelangelo’s mastery of the human form, naked and muscular, conveying the perfection of the Creator’s work. Of course, there were detractors from this viewpoint. Immediately, there was criticism of Michelangelo’s inclusion of characters from Greek mythology and the disrespect this showed to the doctrine of the Catholic church. The majority of those who saw the fresco stood in awe at the artist’s genius, but Pope Paul suffered criticism for allowing the painting to be commissioned and completed, even after it was clear that the nude forms might inflame opinion. Nevertheless, The Last Judgment remained in place.

The Cover-Up: Censorship and the Council of Trent

For decades, the fresco remained in its original form. Then, in 1563, during the latter days of the Council of Trent, it was decreed that nudity in art should be avoided and that existing artworks should have naked figures covered or the work be destroyed. What the Council referred to as “lasciviousness” was destined to be removed from Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

In 1565, Pope Pius IV, following the Council’s instructions, commissioned Daniele da Volterra to paint drapery over the exposed genitals on around forty figures in Michelangelo’s fresco. Whilst this was, no doubt, a valuable papal commission for da Volterra, he became known amongst his peers as Il Braghettone—the breeches-maker.

In later centuries, further additions were made to the work to comply with the conventions of the day regarding what was acceptable in religious art. Thankfully, Cardinal Alessandro Farnese had, in 1549, recognized the magnitude of Michelangelo’s work and had Marcello Venusti copy it in its original composition. This copy now hangs in the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples and shows the uncovered bodies as Michelangelo intended them to be seen.

Between 1980 and 1994, restorers removed approximately half of the draperies and foliage applied over centuries of censorship. The altar wall, along with the vaulted ceiling, had become soot-blackened and dirty. During these restorations, the image of the serpent biting Minos’s (Cesena’s) genitals was rediscovered.

From Blasphemy to Blockbuster: Michelangelo’s “The Last Judgment”

In the centuries since Michelangelo painted his magnificent fresco of The Last Judgment, it has been denigrated and lauded, perhaps, in the first decades after its completion, in equal measure. Christ had not been depicted as the physical equal of a Greek god before. Michelangelo has Christ controlling the swirling turmoil around him. Criticized for its unconventional composition, at once powerful and chaotic, it remains a wonder of the art world.

Few who have had the opportunity to worship at the altar of the Sistine Chapel can fail to have been deeply affected by the prospect of The Last Judgment. To the faithful of the Catholic church, it portrays the final balancing of the scales and the resultant ascendancy to heaven or the plunge into hell. Art lovers see the artist’s genius and incomparable confidence in painting the human form.

The Last Judgment has passed from its initial purpose as a reminder to the clergy of their place in God’s scheme, upholders of Christian belief between the earthly death of Christ and the final reckoning, into the realm of global tourism. However, it retains its original powerful message during papal conclaves when the College of Cardinals comes together to decide on God’s next representative, the pope. There can be no more impressive location to ponder the meaning of The Last Judgment.